At 11:47 a.m. February 19th, 1945, Vincent Castayano crouched in volcanic ash on Ewima, gripping a Winchester Model 12 shotgun that could get him court marshaled. 300 yd ahead, Japanese soldiers waited in caves that had already swallowed 18 Marines from his company. 18 good men dead in 6 days. Eddie McKenna from Boston bled out on black sand while his brothers fired uselessly at shadows.

Danny Chen from San Francisco drowned in his own blood from a grenade they never saw coming. Bobby Morrison from Denver took a bullet through the eye trying to clear a cave with the wrong weapon. Bobby had bunkked three racks down from Vinnie aboard the USS Missoula. Every night for two weeks, Bobby talked about his girl back in Denver.

Her name was Sarah. She worked at her father’s hardware store. Bobby was going to marry her when he got home, buy a little house near the mountains, have kids, live quiet. Bobby died at 23 because the M1 Garand, magnificent at 500 yards, was [ __ ] useless at 15 ft in the dark. Vinnie checked his shotgun one last time.

Six shells loaded, 74 more in his pack. Each shell held nine 33 caliber lead balls. At close range, pulling the trigger once was like firing nine pistols simultaneously. The Marine Corps said shotguns had no place in modern warfare. The Marine Corps hadn’t watched Bobby Morrison die. In the next four hours, Vinnie would kill 62 Japanese soldiers, rewrite how America fights in close quarters, and trigger a diplomatic protest from Tokyo claiming his weapon violated international law.

But that wasn’t why he was doing this. He was doing it for Bobby, for Eddie, for Danny, for every Marine who’d followed the manual into a cave and never walked out. This is the story of how one man’s grief became a doctrine and how a duck hunting shotgun from Philadelphia became the most feared weapon in the Pacific theater. Vincent Michael Castayano learned to kill in two places.

his father’s butcher shop and his uncle’s marshland. The shop was on 9inth Street in South Philadelphia’s Italian market, wedged between a produce stand and a bakery that made the best fugliatel in the city. The smell was sawdust and blood. Vinnie started working the counter at 11:00, breaking down sides of beef, wrapping pork chops, cleaning rabbits that hunters brought down from the pine baronss.

His hands learned to work fast with sharp tools in tight spaces. Blood and guts didn’t bother him. Death was just a transaction. Animal walks in alive, walks out in packages. But the real education happened on weekends. His uncle Tony owned 40 acres of marshland along the Delaware Bay near a town called Fortiscu that barely existed on maps.

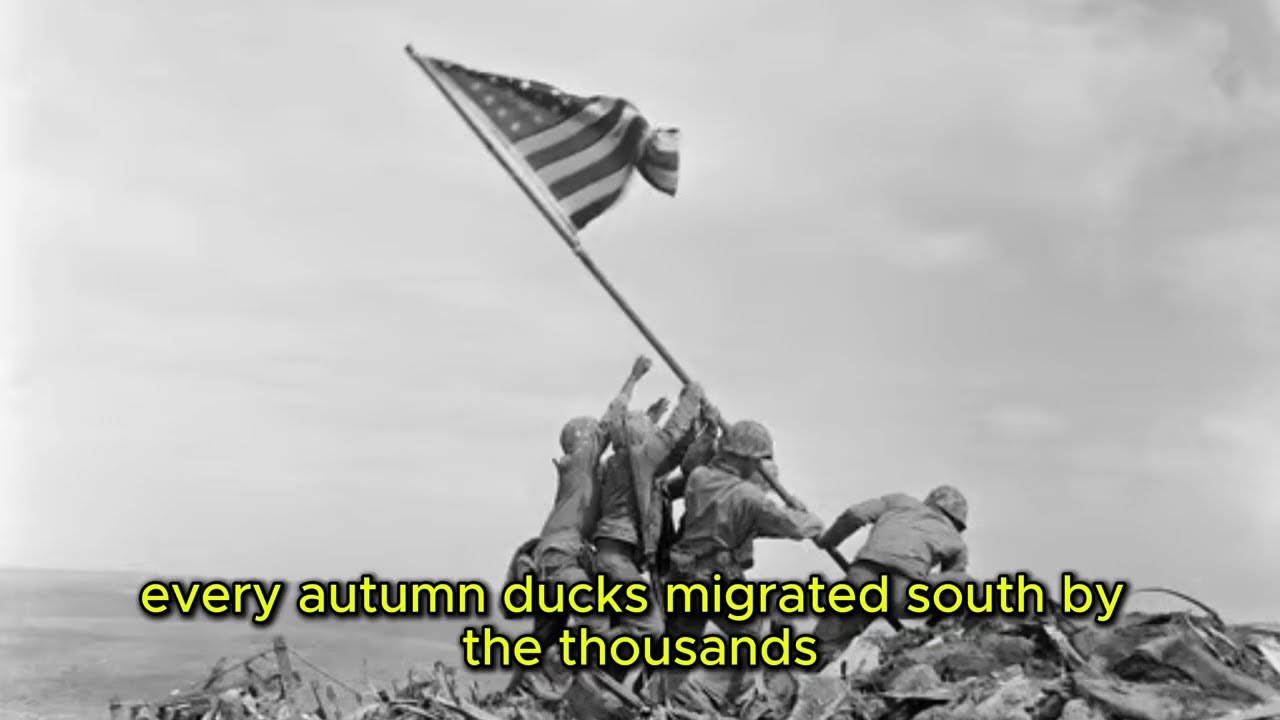

Every autumn ducks migrated south by the thousands. Every autumn Vinnie hunted them, not gentleman’s hunting with expensive overunders and retriever dogs. Workingass hunting, dawn hunts in freezing water. A Winchester Model 12 pumpaction shotgun his father bought him for his 16th birthday. Five shells in the tube magazine. No misses allowed when ammunition cost money your family didn’t have.

Uncle Tony taught him the rhythm. Ducks don’t give you time to think. They come fast. They scatter fast. You got maybe 6 seconds to drop three birds before they’re gone. Miss once, you eat beans that week. Vinnie didn’t miss often. By 17, he could work the Winchester’s pump action faster than most men could blink.

His hands learned the motion so deeply, it bypassed thought. Fire, pump, fire, pump, fire. The shotgun became an extension of his nervous system. Some guys were natural with rifles, needed to aim, needed to breathe right, needed perfect conditions. Vinnie just pointed and killed. December 1942, he turned 18.

Draft notice came 3 weeks later. His mother cried at the kitchen table. His father said nothing, just gripped Vinnie’s shoulder hard enough to leave marks. Uncle Tony wrapped the Winchester in oil cloth and said, “Wars different than ducks, Vinnie. But the gun don’t know that.” Vinnie packed it in his seabag anyway.

Against regulations didn’t care. He had a feeling. Fort Dicks, Camp Llejun, then the Pacific. They handed him an M1 Gan and called it the finest infantry rifle ever made. Semi-automatic, eight round onblock clip, effective range 500 yd. Every Marine qualified expert with it. Vinnie qualified expert, too.

But the rifle felt wrong in his hands. Too long, too slow between shots, no rhythm. It was a weapon for men who aimed. Vinnie had spent six years learning not to aim, learning to point and trust his body. He never mentioned the Winchester, kept it wrapped at the bottom of his seabag through training, through transport, through 14 days aboard the USS Missoula, heading toward an island none of them had heard of.

Ewima, 8 square miles of volcanic rock and sulfur. expected casualties. Hi. That’s when he met Bobby Morrison. Bobby was from Denver, 23 years old, thin kid with a scar on his chin from falling off a bike when he was 12. He’d survivedSaipan and Tinian. Two campaigns. Bobby knew things. How to dig a foxhole that wouldn’t collapse in shelling.

How to sleep through artillery. how to tell the difference between incoming and outgoing fire just by sound. But mostly Bobby talked about Sarah. She’s got this laugh, Bobby said one night aboard the Missoula. Both of them smoking on the deck. Sounds like when you skip a rock perfect across water, you know that clean sound.

Yeah, Vinnie said, even though he didn’t know her dad’s got a hardware store, Johnson’s Hardware. Been there 40 years. I’m going to work there when I get back. Learn the business. Sarah and me will get married, buy a house, have kids, normal life. Sounds good. Bobby looked out at the Pacific. Black water stretching forever.

You got a girl, Vinnie? Nah. Nobody waiting. That’s better. Maybe. Nobody to worry. They stood quiet for a while. Bobby flicked his cigarette into the ocean. You scared? Yeah. Me, too. But we survived. Saipan and Tinian. We’ll survive this. Bobby didn’t survive. D-Day, February 19th, 1945. The naval bombardment was the heaviest in Pacific War history.

For three days, battleships and cruisers hammered Ewima. Bombs, shells, rockets, over 22,000 tons of explosives. Officers said nothing could survive that. They were wrong. The Japanese had spent 9 months carving 11 miles of tunnels through volcanic rock. Caves, bunkers, pill boxes, all interconnected. Artillery couldn’t reach them.

Bombs just rearranged the surface. Deep underground, 21,000 Japanese soldiers waited with orders to never surrender. Every yard in land would cost Marine blood. Vinnie’s company, Alpha Company, First Battalion, 27th Marines, landed on Blue Beach at 9:02 a.m. The beach was chaos. Explosions, smoke, bodies, Marines running for cover while mortars dropped. But they pushed in land.

That was the job. Push until you can’t push anymore. The first cave complex was 400 yd in. Three entrances in volcanic rock. Spider holes everywhere. Tunnels connecting everything underground. Standard doctrine. Suppress with machine guns. Advance with riflemen. clear with grenades. Bobby Morrison’s fire team went first.

Vinnie was 30 yards back, watching. Bobby’s team reached the nearest cave entrance, threw grenades, waited for explosions, moved forward. Machine gun fire erupted from deep inside the cave, from somewhere the grenades hadn’t reached. Bobby went down, bullet through the eye, dead before he hit the ground. Another Marine, PFC Davis from Atlanta, tried to drag Bobby back, took three rounds in the chest, dead.

The rest of the team retreated under covering fire, left the bodies. That night, Corporal Eddie McKenna from Boston died the same way. Different cave, same problem. Grenades couldn’t reach deep enough. M1 Garands couldn’t see far enough in the dark. Marines advanced and died. D plus2 Danny Chen from San Francisco. Grenade from a tunnel they didn’t know existed. Shrapnel to the neck.

Four Marines tried to save him. He drowned in his own blood anyway. D plus3 Private Jackson from Newark. D plus4 Corporal Stevens from Chicago. D plus 5. Lance Corporal White from New Orleans. 18 Marines in six days. All because the weapons were wrong for the job. Sergeant Paul Donovan sat in his foxhole on the night of D plus 6 and did math.

The company had pushed maybe 400 yards. They’d lost 42 men. One marine every 10 yard. The island had miles of caves. At this rate, they’d lose everyone. Vinnie sat in the next foxhole thinking about Bobby, about Sarah in Denver, who’d get a telegram saying her fianceé died heroically. The telegram wouldn’t say Bobby died because nobody had figured out that M1 Garands don’t work in caves.

He thought about Uncle Tony’s marshland. About ducks coming in fast at dawn. 6 seconds to kill. Three birds. No time to aim. About the Winchester Model 12 sitting in his seabag aboard the Missoula. Close quarters. Poor visibility. Fast targets. The M1 Garand was built for France in 1918. Long sight lines, open fields, 500yard engagements.

Ewima’s caves were 10 ft wide and pitch black. You didn’t need accuracy. You needed speed and spread. You needed a shotgun. Vinnie walked to Blue Beach at dawn. Found a Navy enen who looked too young to question anything. Got my father’s watch aboard the Missoula. Need it for morale, sir. The Enson signed authorization without looking up.

20 minutes later, Vinnie stood in the Missoula’s hold, opening his foot locker. The Winchester lay wrapped in oil cloth exactly where Uncle Tony had packed it. 12 gauge, modified choke, five round tubular magazine, pump action, 7 pounds. He’d fired 3,000 rounds through this gun. He knew every scratch on the walnut stock.

He grabbed four boxes of 12 gauge double buckshot, 80 rounds total. The regulation against personal weapons was explicit. The penalty was court marshal, dishonorable discharge, brig time. But standing there, smelling gun oil and feeling the Winchester’s weight, Vinnie did different math. He could followregulations and watch more Marines die.

Or he could break regulations and maybe maybe save lives. He thought about Bobby’s laugh, about Sarah’s hardware store in Denver, about the telegram that said died heroically, but meant died because we sent him into a knife fight with the wrong [ __ ] weapon. Vinnie walked off the masula with the Winchester under a poncho.

Nobody stopped him. That night, Sergeant Donovan walked past Vinnie’s foxhole and saw the shotgun. The hell is that? Castellano. Personal weapon. Sarge. That ain’t issue. No, Sarge. Donovan stared at the Winchester. Then he looked toward the caves where Bobby had died, where Eddie had bled out, where Dany had drowned.

He looked back at Vinnie. I didn’t see that, but if it jams tomorrow, I’m writing you up myself. It won’t jam, Sarge. It better not. Because if you’re right about this, you’re going to save lives. And if you’re wrong, you’re going to Levvenworth. Vinnie Field stripped the Winchester, checked the action, cleaned the barrel with his toothbrush and gun oil he’d traded cigarettes for, loaded six shells, chambered one. He was ready.

He was going to kill every Japanese soldier he could find. for Bobby, for Eddie, for Danny, for every Marine who’d die tomorrow if someone didn’t try something different. February 19th, Dluffy7. 11:47 a.m. Alpha Company received orders to clear cave complex 700 yd inland from Blue Beach.

Intelligence estimated 30 to 40 Japanese soldiers in interconnected tunnels. Standard doctrine. Suppress. Advance. Clear. Vinnie carried the Winchester openly. Now officers saw it. Nobody said anything. Officers on Ewima learned fast. If something might work, you didn’t question it until after the shooting stopped. The cave complex sat in a rgeline of volcanic rock.

Three visible entrances. Machine gun positions covering approaches. This was standard Ewoima terrain. Every yard caused blood. Mortars opened up at 11:55 a.m. Explosions walked across the ridge line. Then machine guns, tracers ripping into cave mouths, keeping defenders deep inside while Marines advanced.

Vinnie’s squad moved forward, 100 yardds. No return fire yet. At 12:18 p.m., Japanese machine guns erupted from positions nobody had spotted. Private Tommy Rizzo from Newark went down, hit twice in the chest. More fire, more grenades. The whole ridge line came alive. Sergeant Donovan pointed at the nearest cave entrance 30 yard away. That one.

We clear it. Standard procedure. Private Jackson threw two grenades. They bounced into the cave mouth. Explosions, dust, and smoke poured out. Jackson and another marine advanced. 20 feet from the entrance. Machine gun fire erupted from deep inside the cave. From where grenades hadn’t reached. Jackson took rounds in both legs.

The other marine dragged him back. This was the pattern. This was why Marines died. Vinnie watched from 35 yd away. Watched Jackson bleeding. watched the cave mouth that had swallowed two grenades and was still sending out fire. He didn’t ask permission. He stood up and ran toward the cave. “Castaniano!” Donovan shouted. Vinnie didn’t stop.

He covered 30 yards in seconds. The cave mouth was 6 ft wide, 5t tall. Machine gun fire came from somewhere inside. He went in. Darkness swallowed him instantly. His eyes hadn’t adjusted. He heard movement to his left, boots on stone, weapon rattling. Vinnie swung the Winchester, fired. The blast lit up the cave interior like lightning.

He saw everything in that flash. The Japanese soldier 5 ft away raising a rifle, face frozen in surprise. The buckshot caught him center mass, nine lead balls at 5t. The soldier went down. Pump. Chamber. Another shell. Keep moving. The tunnel bent right. Voices ahead in Japanese. Sharp. Urgent.

Vinnie came around the corner fast. Two soldiers 10 ft away. One working the machine gun that had killed so many Marines. They looked up. Vinnie fired twice. Pump. Fire. Pump. Fire. Both soldiers dropped. Three shells gone. Three down. This was for Bobby. The tunnel opened into a larger chamber. His eyes had adjusted. He could see maybe 15 ft. Movement everywhere.

Eight, maybe nine Japanese soldiers regrouping, reloading, preparing for the next Marine advance. They weren’t prepared for one Marine already inside their position. Vinnie worked the Winchester like he’d worked it on the Delaware Bay. Fire, pump, fire, rhythm, muscle memory. The shotgun roared in the confined space, deafening.

Muzzle flash strobing like lightning. Japanese soldiers fell. This was for Eddie. He went through six shells in 8 seconds, dropped behind a rock outcropping, reloaded. His hands moved automatically. Five shells into the tube, one in the chamber. This was for Danny. Up again. The tunnel continued deeper. A Japanese soldier appeared from a side passage, rifle raised.

Vinnie fired before the man could aim. Pump. Next target. This wasn’t marksmanship. This was pure aggression and volume of fire. The close quarters negated every Japanesedefensive advantage. They couldn’t use prepared positions, couldn’t leverage interconnected tunnels. One marine with a pump shotgun inside their midst was chaos. Vinnie cleared three more chambers.

The tunnel system was larger than intel estimated, maybe 50 soldiers, not 30, but they were scattered through passages, isolated by turns and darkness. He encountered them in groups of two or three. At 10-ft range with double buckshot, the outcome was decisive. His ears rang. His shoulder achd from recoil.

His hands worked the pump automatically. He’d lost count of shells fired. At 12:51 p.m., he emerged from a different entrance than he’d entered. Sunlight blinded him. Marines saw him, raised weapons, then recognized the uniform. Sergeant Donovan ran over. Jesus Christ. Castiano, what did you do? Cleared it, Sarge. Cleared what? Main tunnels.

Donovan sent a fire team in to confirm. They found 37 dead Japanese soldiers, most killed by shotgun wounds at close range. Multiple pellet wounds, devastating trauma. The tunnel walls, blood spattered, shell casings everywhere. 37 confirmed kills. One marine 43 minutes. Donovan stared at Vinnie. You know what this means? What, Sarge? It means you just proved every tactical manual wrong and saved God knows how many lives.

Vinnie thought about Bobby, about Sarah in Denver, about the telegram she’d already received. He didn’t say anything. Captain Wilkins arrived at 1:15 p.m. Private, where did you get that weapon? Brought it from home, sir. That’s not issue. No, sir. Wilkins looked at the cave, looked at the bodies, looked at Vinnie.

How many shells you got left? Maybe 40, sir. That enough for the next complex? Might be, sir. Wilkins nodded. Alpha Company has orders to clear the ridgeel line. Four more cave systems. You’re taking point. It wasn’t a question. Second cave complex 147 p.m. 200 yd northeast. Heavily fortified. Estimated 50 soldiers inside. Vinnie went in. 17 minutes. 24 confirmed kills.

Third cave complex. 2:31 p.m. 40 yard deep. Multiple chambers. 13 confirmed kills, 11 minutes. Fourth cave complex, 3:18 p.m. Heavily defended. Two machine gun positions inside. Vinnie used grenades first to suppress, then went in with the Winchester. 19 kills, 21 minutes. By 4:15 p.m., Alpha Company had cleared the entire ridge line.

Four cave complexes. Traditional tactics, two days minimum, 30 marine casualties. Vinnie Castellano, four hours, 67 shells, zero friendly casualties in the tunnels. Final tally, 62 confirmed kills. Corman checked him over. You hit? Don’t think so. You’re covered in blood. Ain’t mine. Sergeant Donovan sat next to him in the shell crater.

didn’t speak for a full minute. Finally. That was the craziest thing I’ve ever seen. It worked, Sarge. Yeah, it worked. Donovan lit two cigarettes, handed one to Vinnie. You know they’re going to want to talk to you. Division maybe core. This is going to spread. Don’t care about that. What do you care about? Vinnie looked at the caves, at the bodies being counted, at the Marines still alive because they didn’t have to clear those tunnels the manual way.

Bobby Morrison. Vinnie said he was going to marry a girl named Sarah, work at her dad’s hardware store, have kids, normal life. I knew Bobby, good Marine. He died because we sent him into a cave with the wrong weapon. him and Eddie and Danny and all the others. They followed the manual. The manual killed them.

Donovan exhaled smoke. And you fixed that today for today. But there’s a hundred more caves on this island. A thousand more marines going to die if they keep doing it wrong. So what do you want? I want every Marine to know this works. I want them to have the right tools. I want Bobby’s death to mean Sarah doesn’t get more telegrams about more guys dying the same stupid way. Donovan nodded slowly.

Then you better hope this spreads fast because if Division shuts this down, more Bobbies die tomorrow. Word spread through 27th Regiment by evening. By morning across Ewima, kid from Philadelphia with a pump shotgun cleared caves by himself. Marines started requesting shotguns. Supply officers got inquiries.

Do they have Winchester Model 12s? Any 12-gauge pumps? Answer: No. Shotguns weren’t Marine Corps issue. But Marines are creative. Some found shotguns in Navy supply. Some wrote home asking families to ship them. Within a week, 20 shotguns appeared in frontline units. Lieutenant Mike Harrison from Texas got a Winchester Model 1897.

Took it into a cave complex February 24th. Eight confirmed kills. Cleared two chambers. Came out alive. That kid was right. Harrison told his platoon. This is the tool for caves. Corporal James Woo from Oregon found a Remington Model 31 used it February 26th 12 confirmed kills inside 15 ft.

Woo said nothing touches this. The tactic spread organically. No official doctrine, no training program, just word of mouth among Marines tired of dying. By March 1st D plus18, shotguns were common enough that Japanese soldiers startedreporting them. Radio intercepts. Marines using special close quarters weapons. Extreme damage.

Multiple projectiles. Cannot defend at close range. March 3rd. A recovered Japanese diary. Entry dated March warrant. American devils have new weapon. Fires many bullets at once. Our soldiers fear it. Close combat now suicide. The psychological impact mattered as much as the tactical impact. The sound alone, that distinctive boom in tunnel confines, became terrifying.

Survivors spread word, “Don’t let them get inside.” By mid-March, Japanese doctrine shifted. Instead of waiting inside caves, defenders started collapsing tunnel entrances when they heard shotgun fire. Better to seal themselves in than face that weapon. American intelligence noticed. Fewer casualties.

Clearing caves, faster progress. Before shotguns, six hours per cave complex, multiple casualties. After shotguns, 2 hours per complex, minimal casualties. The math was undeniable. Then came the diplomatic protest. March 8th, 1945. The Japanese government submitted a formal protest through neutral Switzerland. American forces on Ewima were using shotguns in violation of international law.

The HEG convention supposedly prohibited weapons causing unnecessary suffering. The American response was blunt. Shotguns were legal. They’d been used in World War I. The protest was rejected. But the fact that Japan filed it meant one thing. Shotguns were working so well that the enemy wanted them stopped. Lieutenant Colonel Chambers, commanding third battalion, 25th Marines, wrote in his afteraction report, “The introduction of shotguns for cave fighting has proven extremely effective.

Recommend immediate procurement and distribution to all infantry battalions engaged in close quarters combat operations.” February 1921 before widespread shotgun use. Fifth Marine Division 1,127 casualties clearing 40 cave complexes. Casualty rate 28 Marines per complex time per complex average 6.4 hours. March warrant 15 after shotgun adoption.

Fifth Marine Division 723 casualties clearing 70 cave complexes. Casualty rate 10.3 Marines per complex time per complex. average 2.1 hours reduction, 63% in casualties, 67% in time. Conservative estimates credit shotgun tactics with saving 300 Marine lives on Eoima alone, but official recognition was complicated.

The Marine Corps had prohibited personal weapons. Marines had violated that regulation. The tactic worked spectacularly. Now what? March 12th, Colonel Liver Sedge received the report called a staff meeting. We have Marines carrying unauthorized weapons. Technically, this violates regulations. Practically, it’s saving lives. Recommendations.

The debate lasted 2 hours. The compromise. No official authorization. No official prohibition. Individual commanders make their own decisions. The Marine Corps would neither endorse nor condemn. This meant Vincent Castayano received no official recognition, no medal, no commendation. Captain Wilkins tried to submit a Bronze Star recommendation.

It was returned with a note. Cannot award medal for actions involving unauthorized equipment. Vinnie didn’t care. He’d done it for Bobby, for Eddie, for Danny, for every Marine who died because someone followed the manual instead of thinking. The fact that other Marines adopted the tactic, that 300 lives were saved.

That was enough. Vincent Castayano survived. Ewima caught shrapnel marched 21st from a mortar round. Nothing serious. spent two weeks on a hospital ship. Returned to duty in April. War ended August 15th, 1945. He came home to Philadelphia in October. 9inth Street in the Italian market looked exactly the same.

His father’s butcher shop, the produce stand, the bakery. Nothing had changed. Everything had changed. Vinnie went back to work behind the counter, breaking down sides of beef, wrapping pork chops. The Winchester Model 12 went back in the closet. He married Angela Moretti in 1947, a neighborhood girl who’d worked in a parachute factory during the war.

They had three children, Vincent Jr., Marie, and Anthony. Vinnie took over the butcher shop when his father retired in 1959. Every Saturday morning, up at 4:00 a.m., prep the cases, open at 6:00 a.m. Same routine for 34 years. He never talked about the war. Customers asked sometimes Veterans Day, Memorial Day.

You serve, Vinnie? Yeah. Pacific. See action? Some. That was it. No stories about caves. No mention of 62 kills. No explanation of how he’d changed tactics. Just some his children asked once. Teenage curiosity over dinner. What did you do in the war, Pop? I was a Marine. Ewima. Did you fight? Yeah. Did you kill people? Vinnie put down his fork, looked at his son, 14 years old, concerned about algebra tests and girls and normal things.

“War’s not like the movies,” Vinnie said finally. “People die. Sometimes you’re the one who makes that happen. You don’t talk about it because talking doesn’t change it. You just try to live decent after.” “But were you scared?” Vinnie thoughtabout Bobby Morrison’s face in the cave entrance, about Eddie McKenna bleeding out, about Danny Chin drowning in his own blood.

Every day, Vinnie said, “Now eat your dinner.” That was all he’d say. He died January 17th, 1993. Heart attack. 70 years old. He was in the shop cutting meat for Mrs. Dinardo, a customer he’d known 40 years. Collapsed behind the counter. Paramedics said he was probably dead before he hit the floor. The obituary in the Philadelphia Inquirer was three paragraphs.

One mentioned his service. Mr. Castellano served with distinction in the United States Marine Corps during World War II, participating in the Battle of Ewima. Nothing about shotguns. Nothing about cave fighting. Nothing about the 62 men he killed or the 300 Marines his innovation saved. His son Vincent Jr. found the Winchester Model 12 in the closet while cleaning out the house, still wrapped in oil cloth, still in perfect condition.

Why dad keep this? Vincent Jr. asked his mother. Angela shrugged. He used to hunt ducks when he was young, before the war. Did he ever use it after he came back? No, he never hunted again. Never even took it out of the closet, as far as I know. Vincent Jr. almost donated it to Goodwill. Something stopped him.

He called the Marine Corps Museum at Quantico instead. By 1946, the Marine Corps officially adopted shotguns for close quarters combat. Winchester Model 12 and Remington Model 31 became standard issue. Korea 195053. Marines used shotguns extensively in urban combat at Seoul and Inchan. The lessons from Ewima applied directly.

Vietnam 1965 to 75. Shotguns became standard for tunnel rats clearing Vietkong complexes. The tactic Vinnie pioneered became doctrine. Modern era. Every Marine infantry battalion has shotguns in inventory. Close quarters battle training includes shotgun tactics. Urban warfare doctrine specifically addresses shotgun employment.

In 2008, a Marine historian named Dr. Jennifer Wade researched Ewoima tactics, found references to unauthorized personal weapons and shotgun effectiveness. She dug deeper, found Sergeant Donovan’s personal diary, donated to the Marine Corps Historical Center after his death in 1987. Donovan’s entry, February 19th, 1945. Castano went into that cave alone with his pump shotgun. I thought he was dead.

He came out 40 minutes later with 37 kills. Changed everything. Nobody will believe this happened. Wade tracked down Vinnie’s service record. Found Wilkins rejected Bronstar recommendation. Found the Japanese diplomatic protest. Found the casualty statistics. The numbers matched. The story was real.

She tried to find Vincent Castellano. discovered he’d died 15 years earlier. Never told his story publicly, never sought recognition, just uh went back to Philadelphia and cut meat for 47 years. Wade published her research in 2009. Marine officers read it within a year. It was part of small unit leadership training at Quantico.

The case study. How one Marine’s initiative and willingness to break regulations saved hundreds of lives and changed doctrine. Conservative military historians estimate the shotgun tactic pioneered on Ewima saved approximately 2,400 American lives across three wars. Vincent Castayano never knew any of this.

Never knew his name was taught at Quantico. never knew historians credited him with doctrinal innovation. Never knew he’d saved thousands of lives across 50 years. He just knew that on February 19th, 1945, his brothers were dying in caves, and he had a tool that might help. So, he used it for Bobby, for Eddie, for Danny, for every Marine who didn’t have to die the way they did.

That’s how real innovation happens in war. Not through committee decisions in air conditioned offices. Not through years of research and development. Not through official doctrine revisions. Through a bluecollar kid from South Philadelphia who learned to hunt ducks on the Delaware Bay and refused to watch his brothers die when he had a solution in his hands.

Through grief that became purpose. Through rage that became precision. Through love that became doctrine. The Marine Corps eventually gave Vincent Castayano credit 63 years after the fact when he was dead and couldn’t object to the attention. His children learned what their father had done by reading a historian’s book. But the real legacy isn’t in archives or books.

It’s in every shotgun wielding marine who clears a building in Fallujah. Every infantry NCO who trains his squad on close quarters tactics. Every doctrine that exists because one man broke regulations on a volcanic island in 1945. The Winchester Model 12. Vincent Castiano carried on Ewima sits in a display case at the Marine Corps Museum at Quantico.

Now his son donated it in 1994. The placard reads Winchester Model 12 12 gauge pump shotgun used by PFC Vincent M. Castellano at Ewima February 1945. Credited with 62 confirmed kills and pioneering close quarter shotgun tactics. Thousands of people walk pastthat display case every year. Most don’t stop, but some Marines do.

They see the worn walnut stock, the simple pump mechanism, the 12 gauge barrel. They understand this wasn’t about the gun. It was about the man who refused to accept that doctrine was more important than lives. It was about a butcher from South Philadelphia who learned to kill ducks and used that skill to save Marines. It was about Bobby Morrison from Denver who never got to marry Sarah or work at the hardware store or have kids or live normal, but whose death meant something because Vinnie Costelliano made sure it did.

If you found this story compelling, please like this video. Subscribe to stay connected with these untold histories. Leave a comment telling us where you’re watching from. Thank you for keeping these stories alive. Stories alive.

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load