April 1945, a dusty prison camp in Louisiana. 63 German women stepped off military trucks. Their hands were shaking. Their hearts were pounding. They had heard the stories. American captives were cruel. American prisons were death camps. Their own leaders had promised them capture meant suffering. They expected beatings.

They expected starvation. They expected revenge. what they got instead, a plate of hot food. But here’s the strange part. When they took their first bite, they didn’t smile. They didn’t say thank you. Instead, one woman grabbed her water cup and drank it empty in seconds. Another looked at the guard with wide eyes and asked, “Are you trying to poison us?” The American guard just laughed because on that plate sat something these German women had never seen before.

something so salty, so strange, so completely foreign that it made them question everything they knew about their enemy. It was called corned beef and it was about to change how they saw America forever. But what happened next? So that’s where this story gets really interesting. Stay with me until the end because this isn’t just about food.

This is about war, lies, and the moment when enemy becomes human. If you love stories like this, hit that subscribe button right now, like this video, support the channel, and let’s dive into one of the strangest food stories of World War II. It all started when the truck stopped and the gates opened. They arrived expecting the worst.

The truck stopped outside a converted factory building in Louisiana. Spring 1945, the war in Europe was collapsing. Germany was losing. And these 63 women knew what losing meant. They had heard the stories. Enemy prisoners were beaten, starved, humiliated, left to rot in cages like animals. Their own officers had warned them.

Nazi propaganda had promised them. Americans were barbarians. Capture meant death or something worse. So when the truck doors open, the German women braced themselves. They were nurses, radio operators, signal core workers, vermacked auxiliaries who had served behind front lines. Most were in their 20s. Some were younger.

A few were barely 18. They had never fired a weapon. They had never killed anyone, but they wore German uniforms. And now they belonged to the enemy. Guards led them through iron gates, their boots echoed on concrete, their eyes scanned for signs of danger. barbed wire, guard towers, attack dogs. They found all three.

But something else was there, too. The smell. It hit them before they reached the messole. Warm, heavy, salty, almost like seaater mixed with cooked meat. One woman later described it as the strangest smell I had ever encountered indoors. They didn’t know it yet, but that smell was American corned beef, and it was about to confuse them more than any battlefield ever had.

Inside the processing area, American soldiers handed them blankets, clean blankets, then soap, real soap, then a small towel, a toothbrush, and a comb. The women looked at each other. Was this a trick? According to US Army records, American P camps processed over 425,000 German prisoners.

By the end of 1945, the system was massive, industrial, organized, and the rules were clear. Prisoners received the same base rations as American enlisted soldiers, the same food, the same portions, the same meals. This was not special treatment. This was standard policy. But to the German women walking through those gates, it felt impossible.

One former signal operator, Ingred Müller, later recalled the moment in a 1987 interview. “We kept waiting for the real treatment to begin,” she said. “We thought the kindness was a trick, a way to weaken us before the punishment started, but the punishment never came. Instead, the guards pointed them toward the mess hall. Dinner was ready. The building was large and plain.

Metal tables, wooden benches, American cooks in white aprons stood behind a serving line. Steam rose from large pots, trays clinkedked, forks scraped. It looked like any military cafeteria. Nothing threatening, nothing cruel. But for women raised under Nazi rule, the scene made no sense. Enemies were supposed to hate you.

Captives were supposed to hurt you. Yet here they stood, being handed food like guests at a strange family dinner. The trays came out. On each one sat a thick slice of something pinkish red, glistening with fat. Beside it, pale green cabbage, a scoop of mashed potatoes, a piece of bread. The meat looked wet, shiny, almost too pink.

Several women hesitated. A few whispered among themselves. One asked a guard, pointing at the meat. Was this? What is this? The guard shrugged. Corned beef. The words meant nothing to them. Corn beef didn’t exist in Germany. Not like this. Not salted in brine for weeks. Not served this way. They sat down slowly, forks lifted, eyes studied the strange meat.

And in that silence, caught between fear, hunger, and confusion, the first bites began. What happened next would stay with these women for the rest of their lives. Not because of cruelty, but because of the complete absence of it. Because the real shock wasn’t the taste of the meat.

It was the realization that everything they had been told about Americans might be wrong. To understand why corned beef shocked these women, you must first understand where they came from. Germany had a long history with preserved meat, but it looked nothing like what Americans ate. In German kitchens, meat was smoked. It was air dried.

It was ground into sausages with careful blends of spices. Families passed down recipes for generations. A grandmother’s worst recipe was sacred. A butcher’s smoking technique was his livelihood. German preservation was an art. Slow, deliberate, regional. Every part of the country had its own specialty. Bavaria had its vice vers. Tingia had its brat.

The Black Forest had its famous smoked ham. These were not just foods. They were identities. And salt, yes, Germans used salt, but never like this. American corned beef came from a completely different tradition. It was invented out of necessity, not culture. In the 1800s, Irish immigrants in New York needed cheap meat that lasted.

Jewish butchers in Manhattan sold them beef brisket, and the Irish preserved it the only way they knew, packed in massive amounts of coarse salt. The word corned didn’t mean corn, the grain. It meant the large corns or kernels of rock salt used in the brining process. The meat sat in salty water for weeks, sometimes a month. The salt killed bacteria.

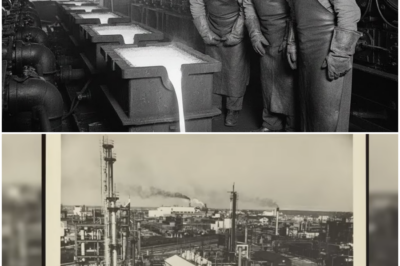

It changed the texture. It turned the beef pink. By World War II, corn beef had become a staple of American military food. It was cheap. It lasted forever. It could be shipped across oceans without spoiling. The US Army purchased over 2.5 billion pounds of canned and processed meat during the war. Corned beef was a significant part of that number. Soldiers ate it in trenches.

Sailors ate it on ships. And now prisoners ate it in camps. But for German women who grew up eating delicate smoked pork and mild herbed sausages, corned beef was an alien substance. One prisoner, Hildebrandt, a nurse captured near the rine, later wrote in her memoir about her first encounter with the meat.

It was so salty that my lips burned, she recalled. I thought the Americans were trying to poison us slowly. I could not understand why anyone would eat this by choice. She wasn’t alone in her confusion. Many German PS, both men and women, reacted the same way. The salt content was overwhelming. The texture was strange.

The pink color looked almost unnatural. Some prisoners genuinely believed the meat had gone bad. In German cooking, pink meat usually meant undercooked meat, dangerous meat. Yet here, the Americans were serving it proudly as if it were a gift. The taste clash went deeper than preference. It was cultural, psychological, almost philosophical.

Germans believed food should be crafted with care. Each ingredient had a purpose. Each flavor was balanced. Meals were expressions of discipline and tradition. Americans, by contrast, prioritized practicality. Food needed to travel. It needed to last. It needed to feed thousands quickly. Taste was secondary to function.

Neither approach was wrong. But when they collided in that Louisiana mess hall, the result was pure confusion. One American cook stationed at Camp Rustin later described the scene to a military historian. Those German gals looked at the corn beef like we had just served them boiled shoes, he said with a laugh.

We kept telling them it was normal. They kept looking at us like we were crazy. And perhaps from their perspective, the Americans were crazy. After all, who would willingly soak good beef in salt water for 30 days? Who would boil it until it turned pink? Who would serve it proudly as if it were a fine meal? The answer was simple. Americans would.

Because in America, this was fine dining for a soldier. It was comfort food. It was home. But for those 63 German women, it was something else entirely. It was proof that they had landed in a country they did not understand. A country that ate food they could not recognize. A country that treated prisoners in ways that made no sense.

And dinner was only just beginning. The mess hall fell quiet. Metal trays sat on wooden tables. Steam rose from the food. Forks rested in uncertain hands. And 63 pairs of eyes stared at the strange pink meat in front of them. This was the moment, the first real bite. Outside, Louisiana humidity pressed against the windows.

Inside, the air smelled thick with salt and boiled cabbage. Ceiling fans turned slowly, pushing the warm air in lazy circles. Somewhere in the kitchen, pots clanged. A cook shouted something in English. The German women understood none of it. They only understood hunger and fear and the confusing meal before them.

One woman lifted her fork first. Her name was Elsa Richter. She was 24, a former telephone operator from Dresdon. She had survived Allied bombing raids that killed thousands. She had seen her city burn. And now she sat in an American prison camp, staring at a slice of wet, salty meat. She cut a small piece and she raised it to her mouth. She chewed.

Her face changed immediately. Her eyes widened. Her jaw slowed. She reached for her water cup and drank half of it in one gulp. “Ming got,” she whispered. “My God.” The women around her watched. Some leaned forward. Others leaned back. A few put down their forks entirely, but hunger was stronger than suspicion.

One by one, they began to eat. The reactions were immediate and varied. Some coughed, some grimaced, a few pushed their trays away entirely. One young woman, barely 19, started laughing. A nervous, confused laugh that spread down the table like a wave. An American guard standing nearby watched the scene with amusement.

He had seen this before with male prisoners. But somehow watching these women react felt different, more human, less like processing enemies and more like hosting confused guests at a very strange dinner party. According to camp records, the standard P ration included approximately 3,300 calories per day.

This was the same amount given to American soldiers in non-combat roles. It included meat, vegetables, bread, and sometimes dessert. By military standards, it was generous. By German standards, it was unbelievable. Back home, civilians were starving. Ration cards limited families to tiny portions of meat per week. Bread was mixed with sawdust.

Children went hungry. Old people died from malnutrition. And here, in an enemy prison, German women were being served more food than their own families could dream of. The paradox was almost too heavy to swallow, heavier even than the salt. One prisoner, Margaret Vogle, later described the moment in a letter to her sister after the war.

“The meat was terrible,” she wrote. so salty I thought my tongue would crack, but I ate every bite because I did not know when food would come again. I did not trust them yet. That distrust was everywhere. It hung in the air like the steam from the cabbage. Every kindness felt like a trap. Every full plate felt like a lie.

Some women ate fast, protecting their trays with their arms, old habits from scarcity. Others ate slowly, watching the guards, waiting for the trick to reveal itself. But the trick never came. The guards didn’t laugh at them. The cooks didn’t mock them. The food, strange as it was, kept coming. One cook, a large man from Texas named Harold Brennan, walked through the messaul, offering seconds.

“More?” he asked, gesturing at the corned beef. “Most women shook their heads. A few held out their trays.” Brennan later told an interviewer, “This ladies were scared of everything. Scared of the food, scared of us, scared of what came next. You could see it in their eyes. All I could do was keep serving and hope they figured out we weren’t going to hurt them.

” By the end of the meal, trays were mostly empty. Not because the food tasted good, but because these women had learned long ago that you never waste a meal. Still, as they filed out of the mess hall, one question lingered in every mind. Why were the Americans being so kind, and what would they want in return? The complaints came quickly.

Within days, American cooks noticed a pattern. German women ate almost everything on their trays. The potatoes disappeared. The bread vanished. The cabbage was tolerated. But the corned beef, half of it came back uneaten. Trays returned to the kitchen with pink slices barely touched. Sometimes just one bite was missing. Sometimes the meat was pushed to the side, hidden under cabbage like evidence of a small crime.

The cooks talked among themselves. What was wrong with these women? Didn’t they like meat? Sergeant Harold Brennan brought the issue to his supervisor. They’re not eating the beef, he reported. They drink all their water. They ask for more bread, but they leave the meat. The supervisor shrugged. It’s good meat, same as we eat.

And that was true. The corned beef served to German PS was identical to what American soldiers received. Same recipe, same salt content, same preparation. There was no difference. But difference wasn’t the problem. Taste was. Camp records from 1945 show that food waste was tracked carefully. The military hated waste.

Every uneaten ounce meant wasted money, wasted shipping, wasted effort. So when patterns emerged, cooks were expected to adapt. And adapt they did. First, they reduce the salt in the cabbage. German women had complained that everything tasted like the ocean. By making the vegetables milder, the overall meal became more bearable. Next, they increased the bread portion.

Bread was familiar. Bread was safe. German PWS ate bread, eagerly, using it to fill their stomachs when other foods seemed too foreign. Then came the potatoes. Extra scoops appeared on trays. Mashed potatoes helped absorb the salt from the beef, making each bite less intense. Finally, someone introduced mustard.

It was a small thing. A yellow squeeze bottle placed on each table, but it changed everything. German women knew mustard. German mustard was famous. Sharp, tangy, perfect with sausages. American mustard was sweeter, milder, almost like a sauce, but it was familiar enough to feel like home. One prisoner, Ursula Kra, later recalled the discovery in an interview.

A woman at my table put mustard on the salty meat, she said. I watched her eat it without making a face, so I tried it, too. The mustard helped. It covered some of the salt. After that, I always used mustard. Word spread quickly through the barracks. Mustard helps, bread helps, potatoes help. Slowly, the women developed strategies to survive corned beef day.

They weren’t enjoying the food, but they were managing it. American cooks noticed the change. Trays started coming back empty. The pink slices disappeared along with everything else. Brennan smiled when he saw it. They’re figuring it out, he told his team. Give them time. Time was something these women had plenty of.

Days turned into weeks. Weeks turned into months. The war in Europe ended. Germany surrendered. But the women remained in Louisiana waiting for repatriation paperwork, waiting for ships, waiting for a country that no longer existed as they remembered it. And during that waiting, something unexpected happened.

The food started to feel normal. Corned beef still tasted salty. It still looked strange. But it no longer shocked them. It became routine, expected, even reliable. One woman, Bridget Stein, wrote in her diary during this period. Tuesday means corned beef. She noted. I do not love it, but I eat it. I am grateful for it.

At home, my mother is eating grass soup. Here, I am eating meat. Real meat. I have no right to complain. That perspective shifted everything. Complaints faded. Suspicion softened. The women stopped expecting cruelty and started accepting reality. The Americans were not trying to poison them. The Americans were not trying to punish them.

The Americans were simply feeding them the only way they knew how. It wasn’t perfect. It wasn’t German, but it was enough. And sometimes enough is the beginning of understanding. The cooks kept serving. The women kept eating and somewhere between the salt and the mustard, two cultures found a strange middle ground. But the real surprise was still coming.

Nobody saw it coming. 8 weeks had passed since the German women first arrived at the camp. 8 weeks of adjustment, 8 weeks of learning, 8 weeks of slowly accepting that this strange American food would not kill them. Then one Tuesday morning, the menu changed. The cooks had received a shipment of canned ham.

It was a welcome break from routine. Ham required less preparation. It tasted milder. It seemed like an easy win. Lunch trays came out with thick slices of pink ham, green beans, and buttered rolls. The cooks expected smiles. They expected gratitude. They expected the German women to celebrate the change. Instead, they got questions.

One woman approached the serving line. Her name was Leisel Hartman. She was 31, a former Vermacht secretary captured near Belgium. She had been in the camp longer than most. She spoke a little English now, broken, careful, but understandable. She looked at the tray. She looked at the cook. Then she asked a question that made Harold Brennan stop midscoop.

Where is the salty meat? Brennan blinked. What? The salty meat? Leisel repeated. The red meat. Very salty. Where is it? Brennan stared at her for a long moment. Then he started laughing. You mean corned beef? He asked. Yes, corned beef. When does it come back? Brennan shook his head in disbelief.

He turned to his fellow cooks. Did you hear that? She wants the corned beef back. The kitchen erupted in laughter, not cruel laughter. Surprised laughter, the kind of laughter that comes when the world stops making sense. For weeks, these women had complained. They had grimaced. They had pushed the meat aside.

They had called it salt blocks. They had joked about turning into pickles. And now they wanted it back. Brennan wiped his hands on his apron. Next Tuesday, he said. Corn beef comes back next Tuesday. Leisel nodded seriously. Good. We will wait. She took her ham tray and walked away. Behind her, other women were having similar conversations.

Several asked guards about the missing corned beef. A few seemed genuinely disappointed. Word spread through the camp within hours. The German women missed the salty meat. It became a story that guards repeated for years. The same dish that once caused confusion was now being requested. The same taste that once seemed like punishment was now expected, even wanted.

How did this happen? The answer was simpler than anyone imagined. Humans adapt. Taste adapts. Comfort adapts. Corned beef had become familiar. It marked the calendar. It signaled routine. In a life with no control, no freedom, no certainty about the future. That routine mattered more than flavor. One prisoner, Gertrude went, explained it years later in a German documentary.

We did not love the taste, she said. But we loved knowing what to expect. Corned beef meant Tuesday. Tuesday meant another week survived. It gave us something to hold on to. There was another reason, too. A deeper one. The women had finally accepted that Americans were not their enemies. Not really. The guards joked with them.

The cooks tried to help them. The food kept coming day after day without cruelty or conditions. Corned beef was part of that realization. If Americans ate this same salty meat willingly, then maybe Americans were not monsters. Maybe they were just people with different tastes, different traditions, different ways of preserving food.

And if Americans were just people, then maybe the war had been built on lies. That thought was dangerous. It shook everything these women had believed. But the evidence sat on their trays every Tuesday. Pink, salty, undeniable. When corned beef returned the following week, something had changed in the mess hall. Women ate without complaining.

A few even smiled as they chewed. One woman raised her water cup toward Brennan in a small toast. He didn’t understand the gesture, but he nodded back. Somewhere between suspicion and acceptance, a wall had fallen. Not a political wall, not a military wall, just a small human wall knocked down by salt and bread and time. And that perhaps was the strangest victory of all.

The war ended, the camps emptied, the women went home, but home was not what they remembered. Germany in 1946 was a nation of ruins. Cities lay flattened. Factories stood silent. Families searched for missing relatives. Food was scarcer than ever. The average German civilian survived on fewer than 1/500 calories per day.

Many survived on less. The women who returned from American captivity carried something unexpected with them. Not anger, not hatred, not stories of torture or abuse. They carried confusion and gratitude and memories of salty meat. One former prisoner, Ingred Müller, arrived in Hamburg to find her childhood home destroyed. Her mother was dead.

Her brother was missing. She had nothing left except the clothes she wore and the memories she carried. “Years later,” she told an interviewer something remarkable. “When I was starving in Hamburg, I thought about that American messaul,” she said. “I thought about the corned beef I once hated. I would have given anything for one slice.

Just one slice of that salty meat I used to push away.” Her story was not unique. Across Germany, returning PSWs told similar tales. They described American camps with disbelief, full meals, clean blankets, medical care, fair treatment. Many Germans refused to believe them. The stories sounded like propaganda, like lies designed to make Americans look good, but they were true.

According to postwar records, the mortality rate in American P camps was less than 1%. Compare that to Soviet camps where up to 30% of German prisoners died from starvation, disease, and execution. American captivity was not pleasant, but it was survivable. Often, it was more than survivable. The food was a symbol of something larger.

American abundance was real. It was not a trick. It was not a bribe. It was simply how Americans lived. They had more food than they needed. They shared it even with enemies. They served corned beef because corned beef was what they ate. For women raised under Nazi ideology, this was impossible to understand at first. They had been taught that Americans were weak, decadent, morally corrupt.

The propaganda painted a picture of lazy capitalists who would crumble under pressure. Instead, these women found a nation so wealthy that even its prisoners ate better than German civilians. A nation so organized that it could feed hundreds of thousands of captured enemies without complaint. A nation that treated women’s soldiers with basic dignity instead of revenge.

The contradiction shattered something inside them. Margaret Vogle, the woman who once wrote about her cracked tongue from too much salt, later became a school teacher in West Germany. She taught history to teenagers and she always included one lesson that surprised her students. I tell them about the corned beef, she said in a 1978 interview.

I tell them how I hated it, how I feared it, how I eventually missed it, and I tell them what it taught me. That enemies are not always what you expect. That kindness can come from strange places. That a meal can change how you see the world. Her students often laughed at the story. Salty meat. That was her big lesson. But Margaret understood something they did not.

She understood that wars end not just with treaties, but with small human moments. A cook offering seconds. A guard nodding at a toast, a plate of food that said without words, “You are still a human being.” The German women who passed through American P camps carried those moments forever. They passed them to their children. They whispered them to grandchildren.

They wrote them in memoirs that historians still study today. And at the center of many stories sat one humble dish. Pink, salty, strange, unforgettable. Corned beef was never about taste. It was about what happens when propaganda meets reality. When fear meets kindness. When enemies discover that the other side is also human. The women came as prisoners.

They left as witnesses. and their testimony echoed for generation. In the end, America’s greatest weapon was not its bombs, its planes, or its armies. It was a steaming plate of salty meat served without hatred to women who expected none. History remembers battles. It remembers generals and treaties and surrender ceremonies.

But sometimes the truest history happens in mesh hall in small moments between strangers in the taste of unfamiliar food that slowly becomes familiar. The German women who first tried American corned beef did not know they were part of something larger. They only knew they were hungry, scared, and far from home.

What they discovered changed them forever. Not the salt, not the pink meat, but the simple act of being fed by an enemy who chose not to act like. That is the lesson of this story. That humanity survives even in war. That meals can carry meaning. And that sometimes the strangest food teaches the deepest truth.

News

“Don’t Leave Us Here!” – German Women POWs Shocked When U.S Soldiers Pull Them From the Burning Hurt DT

April 19th, 1945. A forest in Bavaria, Germany. 31 German women were trapped inside a wooden building. Flames surrounded them….

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft DT

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory in Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

Inside Ford’s Cafeteria: How 1 Kitchen Fed 42,000 Workers Daily — Used More Food Than Nazi Army DT

At 5:47 a.m. on January 12th, 1943, the first shift bell rang across the Willowrun bomber plant in Ipsellante, Michigan….

America Had No Magnesium in 1940 — So Dow Extracted It From Seawater DT

January 21, 1941, Freeport, Texas. The molten magnesium glowing white hot at 1,292° F poured from the electrolytic cell into…

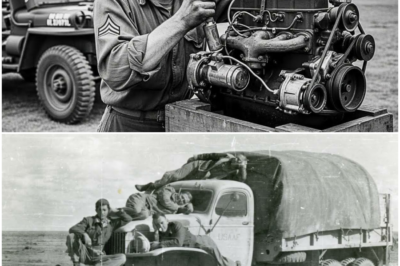

They Mocked His Homemade Jeep Engine — Until It Made 200 HP DT

August 14th, 1944. 0930 hours mountain pass near Monte Casino, Italy. The modified jeep screamed up the 15° grade at…

Beyond the Stage and the Stadium: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Unveil Their Surprising New Joint Venture in Kansas City DT

KANSAS CITY, MO — In a world where celebrity business ventures usually revolve around obscure crypto currencies, overpriced skincare lines,…

End of content

No more pages to load