Imagine standing on the deck of a warship. The night shattered not just by enemy fire, but by the sheer unbelievable volume of shells your own side is throwing back. That’s the scene Captain Tamichi Har, a man who would become the only Japanese destroyer commander to fight from Pearl Harbor all the way to the final surrender, witnessed again and again. What he saw wasn’t just battle.

It was a revelation that shook the very foundations of how Japan thought it could win the war. He famously said, “The Americans used shells without thinking while we counted every round.” Think about that for a moment. Not just more shells, but firing without thinking, like water from a hose instead of carefully measured drops. This wasn’t mere extravagance.

It was a symptom of something far larger. Something happening thousands of miles away in the heartland of America that would ultimately decide the fate of empires in the vast Pacific. This story isn’t just about gunfire. It’s about the staggering, almost unimaginable industrial power that backed every American sailor and soldier.

A power that Japan tragically underestimated. It’s the story of how factories, logistics, and sheer production capacity became the ultimate weapon. Now, let’s go back to November 13th, 1942. Iron Bottom Sound near Guadal Canal, a place already infamous for the ship sunk there. It’s just before 2:00 a.m. Captain Har is on the bridge of his destroyer, the Amatsu Kazi.

Search lights cut through the darkness, and then the sky erupts. American shells are landing everywhere, not with precision, but with overwhelming density. Harra scribbled in his log, horrified. They are not aiming. They are simply filling the sky with metal.

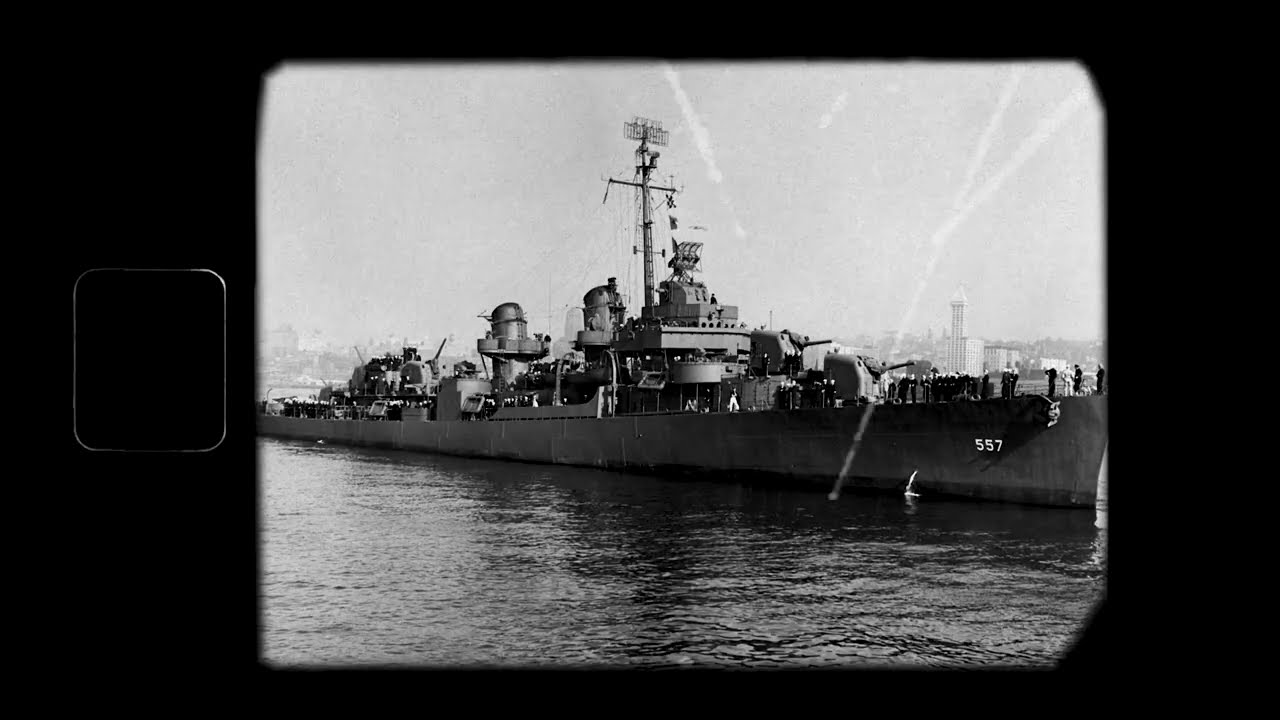

In the chaos of that night, the American cruiser USS San Francisco unleashed a torrent of 5-in shells. In less than a minute, she fired more rounds than some Japanese destroyers like Hara’s carried for an entire mission. Think about that difference. One ship in one minute outshooting another ship’s entire combat load. The Americans weren’t just fighting.

They were creating walls of fire, turning night into a terrifying artificial daylight. Their gun barrels glowing red hot from the relentless pace. But here’s the truly chilling part. The part that reveals the deeper truth Harrow was witnessing. While those American guns were still hot, nearly 3,000 m away in Pearl Harbor, ammunition ships were already loading the next massive shipment. Now, 15,000 tons of shells heading west.

enough to replace everything the American fleet would fire in that brutal Guadal Canal battle 50 times over. Meanwhile, back in Tokyo, naval planners were agonizing over calculations. Could they possibly spare just 12 rounds per gun for the ships heading out on the next vital convoy run? 12 rounds.

The numbers themselves were writing the story of defeat, long before the final surrender. This disparity wasn’t just about shells. It mocked every single assumption the Imperial Japanese Navy had made about fighting the United States. They had planned for a war of skill, of spirit, of decisive battles, not a relentless grind against an opponent who seemed to have an infinite supply of everything.

Hara survived that night and many more knights like it. He saw firsthand how this difference in ammunition wasn’t just a detail. It was everything. It changed tactics. It changed strategy. It changed the very psychology of the men fighting on both sides. But the seeds of this realization were planted even earlier, though few grasp their meaning at the time.

6 months before Har’s harrowing night at Guadal Canal during the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942, Commander Teeshi Naidito aboard the carrier Shukaku noticed something strange. American cruisers and destroyers protecting their carriers kept up anti-aircraft fire for 4 hours straight. They never seemed to pause, never seemed worried about running low. He later told interrogators, “Each American destroyer appeared to carry more anti-aircraft ammunition than our entire destroyer division combined.

This seemed impossible based on Japanese experience. Their own naval doctrine honed over decades assumed every navy faced similar limits. Take Japan’s standard light anti-aircraft gun, the type 9625 mil limit. Firing protocols were incredibly strict. Don’t fire until the plane is within 800 m. Fire only short bursts, 3 to five rounds. Stop firing the instant the target moves out of optimal range.

Why? Not because it was the best way to shoot down planes, but because they simply didn’t have the ammunition reserves to do anything else. Lieutenant Commander Masatake Okumia, serving on the carrier Ryujo, trained his gunners relentlessly on these rules. Every man knew their ship held enough ammo for exactly 12 minutes of sustained anti-aircraft fire. 12 minutes.

After that, they were practically defenseless against the air attack. Yet, Okumia noted with growing unease, the Americans seemed to fire continuously for hours on end. It didn’t make sense according to their worldview, but the brutal reality would become undeniable at Guadal Canal where the cold hard math of industrial war met the fierce fighting in Iron Bottom Sound.

Even earlier, the Battle of the Java Sea in February 1942 offered another clue, masked by a tactical Japanese victory. Hara commanding the Amatsu Kazi then too saw the combined Allied fleet American, British, Dutch, Australian, fire over 11,600 rounds of heavy 8-in shells. Their accuracy was poor, only five hits, and four of those were duds. The Japanese fired far less, but scored the hits that mattered, sinking ships.

A clear win, right? But Harris saw something else that troubled him deeply. He noted it in his afteraction report. The Allied ships never stopped firing. They never seemed concerned about running out. They kept up rates of fire that would have emptied Japanese magazines within the first hour. They fired as if they had unlimited shells, Hara wrote years later in his memoirs.

Yes, their gunnery was poor, he admitted, but they had such wealth of ammunition that accuracy became secondary to volume. They could afford to miss because they could afford to keep shooting. After the battle in the wardroom, Hara overheard his gunnery officer, Lieutenant Yoshida, doing the math.

Captain Yoshida reported grimly, we used 40% of our main battery ammunition in that fight. if it had gone on another two hours. Hara silenced him, but the implication was clear. Amatsukaz had started with 2,000 rounds for her main guns. They’d burned through 800 in one engagement. Survivors they rescued from the sunken British cruiser HMS Exit told them their ship alone had fired over 1,500 rounds from its 8-in guns, more shells than most Japanese heavy cruisers carried in their entire magazines. This wasn’t just a difference in degree. It was a difference in kind.

The Allies were fighting a different type of war, one fueled by an industrial engine the Japanese hadn’t fully comprehended. And then came Guadal Canal. When the Americans landed in August 1942, the Imperial Navy’s immediate response laid bare the ammunition crisis.

Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa raced south from Rabaul with a powerful striking force of cruisers and destroyers. How much ammunition did they carry? Enough for exactly one night battle. Not because that was tactically ideal, but because that was literally all the ammunition available at the major forward base of Rabba.

The battle of Tsavo Island on August 9th seemed like another brilliant Japanese victory. In just 33 minutes, Macawa’s ships sank four Allied heavy cruisers. A devastating blow. Japanese losses zero. A tactical masterpiece. But behind the victory was a strategic disaster waiting to happen.

Commander Toshikazu Omi, Mikawa’s operations officer, confessed later, “We withdrew immediately after the battle, not from fear of air attack, as you believed, but because we had exhausted most of our ammunition. We had nothing left for a second engagement.” Think about that. The American transports filled with troops and critical supplies for the Guadal Canal beach head lay vulnerable, practically defenseless just miles away. But Macawa turned back.

Why? Because his victorious ships literally couldn’t afford to shoot at them anymore. They had fired just 471 shells total in the battle. And even that modest expenditure achieving a respectable hit rate by Japanese standards was later criticized back in Tokyo as being wasteful. Meanwhile, what was happening back in Pearl Harbor? Captain William Poco Smith was overseeing the loading of the ammunition ship USS Reineer.

Her cargo for just this single trip, 5,000 tons of naval ammo. That included 350,000 rounds of 5-in shells, over a million rounds of 40 million, and 3 million rounds of 20 million anti-aircraft ammunition. Just one ship carrying more ammunition than the entire Japanese combined fleet would manage to fire in the next three grueling months of the Guadal Canal campaign.

It’s hard to even wrap your head around that scale. And this brings us to the famous Tokyo Express runs. Those desperate high-speed night missions by Japanese destroyers trying to ferry supplies and reinforcements down the slot to Guadal Canal. These runs became a symbol of Japanese tenacity, but they also highlighted the pathetic state of their supply situation, especially ammunition.

Consider Rear Admiral Riso Tanaka’s run on November 30th, 1942. He led eight destroyers. What vital cargo were they risking these valuable ships for? Captured documents showed 100 drums of rice, 200 drums of medical supplies, and just 280 drums of ammunition for 15,000 starving besieged soldiers on Guadal Canal. Less than 300 drums of ammo.

Each drum held maybe 300 rifle rounds or the equivalent weight in grenades or mortar shells. The entire garrison was surviving on deliveries that a single American destroyer might blast away in 20 minutes of intense combat. Captain Hara, commanding a Matsucaz on some of these very runs, wrote bitterly in his diary, “We risk eight destroyers, dozens of lives, tons of fuel to deliver what the Americans probably waste in target practice.” He was closer to the truth than he could have imagined. On that exact same day, November 30th, the

American destroyer USS Fletcher conducted a routine gunnery exercise off Guadal Canal. Just practice. They fired 127 rounds of 5-in ammunition, roughly equivalent to half of one precious drum from Tanaka’s entire cargo run. This staggering difference wasn’t just happening at sea.

It originated deep within the industrial hearts of both nations. While Japan struggled, America was building an ammunition production machine on a scale the world had never seen. Take the naval ammunition depot in Hastings, Nebraska, right in the middle of the country, far from any ocean. It came online in March 1943.

Built on 48,000 acres, that’s over 75 square miles, with 2,200 buildings, its own railroad network stretching over 200 m. At its peak, 10,000 Americans worked there around the clock. This single facility in Nebraska produced 40% of the entire US Navy’s ammunition during the war.

In its first month of operation, Hastings produced more naval ammunition than all of Japan’s facilities combined would manage for the rest of 1943. It specialized in the workhorse 5in duck 38 caliber shell. Starting at 100,000 rounds a month, production climbed to 300,000 rounds per month by September 43. And the quality control was ruthless. They rejected more faulty ammunition than Japanese factories produced in total.

Another giant, the Naval Ammunition Depot in Mallister, Oklahoma, opened around the same time, focusing on larger shells and aerial bombs. By December 1943, its monthly output included tens of thousands of shells for cruisers and battleships, plus hundreds of thousands of pounds of bombs. Nearly 9,000 people worked there by 1945. Now, compare that to Japan.

The Kur Naval Arsenal, their top facility, struggled to make 10,000 shells of all types per month. The Toyokawa Naval Arsenal, expanded before the war, did better with machine guns and small arms ammo, but only by employing a staggering 56,000 workers, including 6,000 conscripted school children, some as young as 12, working in incredibly dangerous conditions.

This industrial avalanche truly crashed down at the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944. often called the Great Mariana’s Turkey Shoot. Vice Admiral Ozawa gathered Japan’s remaining carrier strength. Nine carriers, nearly 500 aircraft for what they hoped would be the decisive battle to turn the tide. Facing him was Admiral Raymond Spruent with 15 carriers and almost a thousand aircraft. But the crucial difference wasn’t just the number of planes.

It was the ammunition backing the American fleet. Lieutenant Sadamu Takahashi, a zero pilot who survived being shot down, described flying towards the American fleet. The sky turned black with explosions, not aimed shots, a solid wall of fire. They were filling every cubic meter of air with steel.

The American ships fired like machines. 5-in guns pounding out 15 rounds a minute. 40 mm cannons firing 120 rounds a minute. 20 mm spraying 450 rounds a minute. One destroyer, USS Stockham, fired 12,000 rounds of 40 mm and 20,000 rounds of 20 millm in just 6 hours. Commander David Mccell, America’s top naval ace, watched from above.

The Japs flew into a curtain of fire. Our ships weren’t aiming at individual planes. They were creating zones of death that nothing could fly through. The results were brutal. Japan lost nearly 500 aircraft and three carriers. America lost just 29 planes in combat. The cost in ammunition for the US around 200,000 rounds of 5 in half a million 40 mm and over a million 20 mm rounds. But for the US Navy, this was sustainable.

For Japan, it was irreplaceable. Rescued Japanese pilots echoed Takahashi. It was not battle. It was execution by machinery. If you find this kind of deep dive into the realities of war compelling, hitting that like button really helps us know what topics resonate most with you. Then came the battle off Samar in October 1944.

Perhaps the most legendary mismatch of the war. Admiral Karita’s powerful center force, battleships, including the giant Yamato, heavy cruisers, destroyers, stumbled upon Taffy 3, a small group of American escort carriers, slow, thin skinned ships designed to support landings, not fight battleships.

Protected by just a handful of destroyers and even smaller destroyer escorts. Complete tactical surprise for the Japanese. It should have been a massacre. What happened next became naval legend. Commander Ernest Evans on the destroyer USS Johnston didn’t hesitate for a second. “All hands to general quarters, prepare to attack major Japanese fleet units,” he ordered, charging towards the battleships.

In the next hour, Johnston pumped over 200 rounds from her 5-in guns into the heavy cruiser Kumano, wrecking her superructure. Then she took on the battleship Congo. And her gunners weren’t aiming for kill shots. They were just pouring out fire at the maximum possible rate, trying to distract and disrupt. Meanwhile, on the tiny destroyer escort, USS Samuel B.

Roberts, a ship half the size of Johnston, Lieutenant Commander Robert Copelan told his men, “This will be a fight against overwhelming odds from which survival cannot be expected. We’re going in.” What he didn’t need to tell them was their desperate ammunition situation by American standards. Just 325 rounds per gun.

Yet in the next 35 minutes, one of Robert’s gun mounts fired over 600 rounds. Nearly 40% of the ship’s entire supply, firing so fast the barrel glowed white hot. Gunner’s mate, Paul Carr, kept firing his gun manually after power failed until a catastrophic explosion hit the mount. He was found dying, still trying to load one last shell into the ruined gun breach.

He received the Medal of Honor postumously. On the Japanese side, the mighty Yamato fired her colossal 18.1 in guns at surface targets for the first and only time. But her shells were armor-piercing, designed to fight other battleships. They punched straight through the flimsy escort carriers without exploding. Admiral Ugaki, commanding the battleships, wrote in his diary that night about the American destroyers charging through smoke, firing continuously.

Such expenditure of ammunition for such small ships, he marveled. It defies calculation. The battle statistics are stark. The Americans fired roughly 20,000 rounds. The Japanese with vastly superior firepower on paper fired only about 3,000. Taffy 3 lost ships and brave men, but they achieved the impossible.

They turned back Karita’s force, saving the vulnerable landing beaches at Lady Gulf. They did it with courage, sacrifice, and by firing every round they had, knowing that somehow more would come. By late 1944, the sheer scale of American ammunition production was almost beyond belief. We’re talking 47 billion rounds of small arms ammo produced during the war.

Enough, as one general quipped, for 10 shots at every man, woman, and child on Earth. In just one month, November 1944, the US produced 3.5 billion rifle and pistol rounds, over a million 5-in shells, millions of anti-aircraft rounds, and tens of thousands of heavy battleship and cruiser shells. Japan’s total production for the entire war was estimated around 15 million rounds of all types.

The Crane Naval Ammunition Depot in Indiana, another inland giant, employed 10,000 workers and had storage for 400,000 tons of ammunition, twice the entire estimated ammunition reserve of the Japanese Navy at the start of the war. The human side tells the same story. American workers at Hastings had dorms, cafeterias serving thousands of meals daily, even bowling alleys and movie theaters. They earned good wages at Toyokawa in Japan.

12-year-old Akiko Sato worked 12-hour shifts filling shells, often hungry, seeing classmates die in accidents. We produced maybe 100 shells daily in our section, she wrote after the war. The Americans probably fired that many in one second. This ammunition crisis crippled Japan in ways beyond just the front lines. Training suffered terribly.

Japan’s leading surviving air race, Saburo Sakai, revealed that new pilots in 1944 got maybe 60 hours of flight training compared to 700 plus hours earlier in the war. Gunnery practice, they fired maybe 100 rounds total. American pilots fired thousands in training. Ammunition was practically unlimited for practice.

Enen Koshiro Oawa, trained in late 44, fired his guns exactly three times, 30 rounds total, before his first combat mission. The American pilot he faced likely fired that many in the first second of engagement. Anti-aircraft gunners faced an even worse situation. Remember the Japanese doctrine, hold fire until 800 m. That was pointblank range for fastmoving aircraft.

They did it purely to conserve ammo, knowing the hit probability was low at longer ranges. American gunners like Seaman Robert Scott on the USS New Jersey trained differently. We fired at everything. I probably fired 50,000 rounds in training. Muscle memory took over. I didn’t think about ammunition. I just filled the sky with lead. And then there was the American logistics miracle.

the fleet train service squadron 10. This floating supply base included dozens of oilers, ammunition ships, refrigerated food ships, hospital ships, tugs, even escort carriers bringing replacement planes, all protected by destroyers. In one massive replenishment operation in July 1945, they delivered over 6,000 tons of ammunition, nearly 400,000 barrels of fuel, thousands of tons of food, almost 100 replacement aircraft, all while at sea, keeping the fleet fighting continuously.

That single top off delivered more ammunition than most Japanese naval bases held in total. Admiral Toyota, the combined fleet commander, admitted after the war they simply couldn’t imagine this scale. If we could afford 1,000 rounds, we assumed they might have 3,000. The reality they had 100,000 was beyond imagination.

The final tragic voyage of the battleship Yamato in April 1945 embodies this disparity. Operation Tango was a suicide mission. Yamato sailed with a full load of her massive main battery shells. Essentially every suitable shell left in Japan, but her secondary and anti-aircraft guns had severely reduced loads, enough for maybe 12 minutes of sustained AA fire.

Captain Aruga told his crew, “We sail with enough ammunition for one battle. There will be no resupply.” Facing hundreds of American aircraft, Yamato’s AA fire, initially described as tremendous, quickly dwindled. A survivor, Mitsuru Yoshida, described the end. The 25 millm guns fell silent first, no ammunition, then the 127 mm guns.

Finally, even the main battery had nothing left. We were a 70,000 ton target, nothing more. The American carriers launching those strikes had just been fully resupplied days earlier. They knew more ammo was always on the way. Back in Japan, the shortages led to desperate measures. Ancient temple bells, some centuries old, were confiscated and melted down for their copper, bronze statues, national treasures, met the same fate.

Even household pots and pans were collected. They melted 45,000 temple bells, 90% of all bells in Japan. One 500 KUA bell yielded enough brass for about 2,000 small shell casings, which a single American 40mm mount could fire off in just 16 minutes. Imagine centuries of history and culture consumed in minutes by the relentless machinery of war.

Does hearing about sacrifices like that, the melting of history for just minutes of defense, make you reflect on the true cost of total war? Let us know your thoughts in the comments. Understanding different perspectives is crucial. Beyond the sheer numbers, American technology widened the gap. The proximity fuse, a tiny radar in each shell developed at John’s Hopkins, was revolutionary.

Shells no longer needed a direct hit. They exploded when near an aircraft, increasing AA effectiveness by hundreds of percent. This program cost a billion dollars in 1940s money, a staggering sum, representing 5% of Japan’s entire gross national product for 1944. America produced 22 million of these fuses.

When Japanese Admiral Hagawa saw them in action, he reported it wasn’t warfare, but witchcraft by mathematics. American fire control systems using radar, gyros, and mechanical computers allowed accurate fire day or night in any weather. Japanese systems remained largely manual, optical, useless in the dark or bad weather.

As one Japanese captain admitted, “We aimed by eye while they aimed by machine. Every American shell was directed by mathematics we couldn’t match.” This overwhelming firepower led to incredible stories of survival. The destroyer USS Lafy endured 22 kamicazi attacks in 80 minutes, taking multiple hits, but surviving because her guns never stopped blazing, shooting down nine planes and damaging others.

Contrast that with the Japanese destroyer Yahagi, escorting Yamato, whose AA guns fell silent after 45 minutes due to lack of ammo, leaving her helpless. The ammunition advantage bred confidence in American sailors. They knew supplies were endless. We joked that we could shoot at seagulls for target practice, recalled one sailor. This led to aggressive tactics, destroyers charging battleships, small escorts taking on cruisers.

They fought like David against Goliath. But this David had unlimited stones. For the Japanese, it was the opposite. Every shot required agonizing calculation. Can I afford this shot? That hesitation, born of scarcity, was fatal. The captured commander Fukuda wept when he saw USS New Jersey fire more shells in practice than his ship carried into battle. “How do you fight such wealth?” he asked.

Ultimately, the war wasn’t just decided on the waves or in the air. It was decided by economics, by industry. America’s GMP dwarfed Japan’s. But the difference in ammunition production capability was even more extreme. The US used more copper just for shell casings than Japan consumed for all its needs combined. Lead for bullets, a 15 to1 advantage for the US.

And this doesn’t even count the losses Japan suffered trying to transport what little ammunition they had. American submarines sank over half of Japan’s ammunition shipments. Hundreds of thousands of tons lost at sea. Logistics officers despared. One Commander Tanaka in the Philippines committed suicide, leaving a note. I send empty ships to die.

The Americans sink them full or empty. Our guns fall silent while theirs never stop. When the emperor announced surrender, he spoke of the atomic bomb. But military leaders knew the war was already lost, mathematically decided by industrial might. Admiral Toyota put it plainly. We could not fight without ammunition.

The Americans had infinite amounts. We had whatever we could salvage from our grandfather’s temples. On the last full day of the war, the Cure Arsenal produced 73 shells. Hastings produced 45,000 and was told to cut back. Captain Hara’s words echo, “Americans use shells without thinking. We counted every round.” It wasn’t just a difference in tactics.

It was the difference between an industrial giant and a nation fighting beyond its means. The war wasn’t won solely by courage, though there was immense courage on both sides. It was won by the relentless, overwhelming output of American factories. As Hara concluded, we brought swords to a machine gun fight. The Americans didn’t defeat our navy, their factories did.

That staggering ratio, 47 billion rounds to maybe 15 million, tells the story. It’s a story of industrial capacity transforming warfare. A story written in brass casings across the Pacific floor. It’s a sobering reminder that in modern conflict, the ability to produce and supply can be as decisive, if not more so, than battlefield bravery itself. Understanding these hard truths of history is vital.

We cover stories like this regularly, focusing on the real factors behind major events. If you appreciate this approach, consider subscribing so you won’t miss our future explorations. You can also find another video right here about suggest related topic like US logistics or specific battle that delves deeper into this era.

Thank you for joining us today and reflecting on this critical aspect of the Pacific

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load