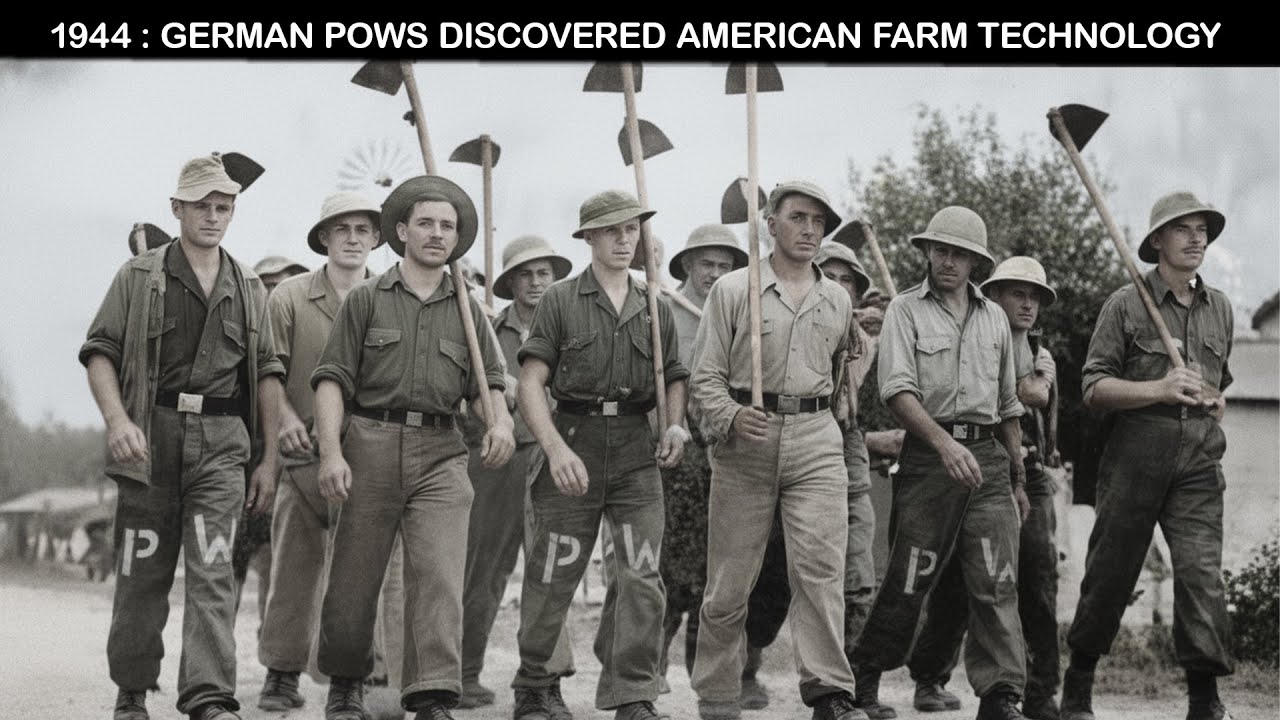

Camp Clarinda, Iowa. July 1944. Aubbridge fighter Hans Mueller stood in the wheat field under the brutal Iowa sun and laughed. Around him, 40 other German prisoners of war, former soldiers of the werem who’d surrendered in North Africa or Italy joined his mockery. Look at this, Mueller said in German, gesturing at the endless fields stretching to the horizon. Thousand hectares, maybe more.

And I’ve seen perhaps 10 Americans working it. 10. In Germany, this would require 200 men minimum. His comrade, Unterizier Kurt Weber, wiped sweat from his forehead and nodded. The Americans are lazy. They have all this land, all this wealth, and they lack the discipline to work it properly. No wonder they needed us to win their war for them. The Germans had been at Camp Clarinda for 3 weeks.

The camp commandant, facing a severe labor shortage. Most American farm workers were in uniform overseas, had contracted the PS to local farmers for agricultural work. The Geneva Convention permitted this, and the wages went to the P fund. But the Germans saw it differently.

They saw vast, wealthy farms with almost no workers, fields that would take platoon of German peasants weeks to harvest, barns filled with equipment they didn’t recognize, and everywhere the sense that Americans had plenty but worked little. Look at him,” Mueller said, pointing at the farmer who’d hired them. A man named Tom Henderson, 60 years old, weathered face, overalls, and a quiet demeanor.

Henderson was examining some piece of machinery in his barn while the 40 Germans stood idle, waiting for orders. He’ll tell us to harvest by hand. Weber predicted, “These American farmers have no organization, no discipline. They’ll work us from dawn to dusk with hand tools because they don’t know better.” Mueller grinned. “Let them.

We’re prisoners anyway. At least we’re not being shot at, and we can show these soft Americans how real German workers operate. Maybe they’ll learn something about discipline and efficiency. Henderson walked over, accompanied by the camp guard and an interpreter. He looked at the assembled PS and said something in English.

The interpreter translated, “Mr. Henderson says, “You can rest in the shade. He’ll handle the harvest this afternoon.” The Germans looked at each other in confusion. “All of it?” Müller asked through the interpreter. This entire field by himself. Henderson nodded when the question was translated.

He walked back to his barn, climbed into something the Germans had seen but not understood. A massive green machine with rotating blades and a hopper, and started the engine. The sound was deafening. The machine lurched forward, entered the wheat field, and began moving at walking pace.

And the wheat disappeared into it, cut, threshed, separated, cleaned, all in one pass. The grain poured into the hopper while the chaff blew out the back. In one hour, Henderson covered what would have taken 40 men with sides and hand threshing three days to complete. Miller and Weber stood watching, their mockery dying in their throats. By evening, Henderson had harvested the entire field.

40 acres alone in his machine. The Germans stood leaning on the shovels they hadn’t used. Watching this quiet Midwestern farmer do the work of a battalion, watching the combine harvester, a machine most of them had never imagined existed, transform agriculture from manual labor into industrial process.

This is the story of how German prisoners of war discovered that they’d lost not just a military conflict, but a civilizational race. How soldiers learned that American laziness was actually efficiency. How the mechanization of American agriculture revealed why Germany never stood a chance. This is the story of the moment when German mockery died in an Iowa wheat field.

The captives from Africa corpse to Iowa corn fields. Between 1943 and 1946, the United States held over 371,000 German prisoners of war in camps scattered across the country. They came in waves. survivors of Raml’s Africa corpse after Tunisia, prisoners from the Italian campaign, captured soldiers from Normandy and the Bulch.

The Geneva Convention required that PS be treated humanely, fed adequately, and housed in conditions comparable to the captive nation’s own troops. The US took these obligations seriously, perhaps too seriously for some Americans who’d lost sons in combat. But there was a problem. The American home front faced severe labor shortages. Millions of men were overseas fighting. Agriculture, essential to feeding both America and its allies, was desperately short of workers. The solution was obvious.

Put the PWs to work. By 1944, over 500 P camps and branch camps existed across the United States, many in rural areas where agricultural labor was most needed. The largest concentration was in the Midwest and South, places where vast farms normally required large seasonal workforces. Camp Clarinda in Iowa held approximately 4,000 German PSWs at its peak.

Branch camps extended into Nebraska, Kansas, and Missouri. The prisoners were contracted to farmers for harvesting, planting, and general farm work. They were paid 80 cents per day, credited to their POW accounts, transported under guard, and returned to camp each evening. For many Germans, this was a surreal experience.

They’d been fighting in deserts, mountains, and forests. Now they were in the American heartland, a place many had never imagined existed. Aubbridge fighter Hans Mueller had served in the 21st Panzer Division in North Africa. He’d surrendered in Tunisia in May 1943 and spent months in transit camps before arriving in Iowa in early 1944. His impression of America was colored by Nazi propaganda.

He expected a bureaucratic society on the verge of collapse. Decadent cities, oppressed workers, racial chaos, incompetent leadership. What he found in Iowa confused him. The farmers weren’t oppressed. They owned vast tracks of land. Their houses had electricity, running water, indoor plumbing. Their children were healthy and wellfed.

Their barns contained equipment Mueller didn’t recognize. This doesn’t match what we were told,” Mueller wrote in a letter to his wife that was intercepted by camp sensors. “The Americans seem wealthy, but they work so little. I see farms with hundreds of hectares managed by one family. No workers, no labors.

How do they do it? Are they simply letting the land go to waste?” Other PSWs shared his confusion. Enturazier Curt Weber, a veteran of the Italian campaign, observed, “German farms are worked by extended families, hired laborers, and seasonal workers. Everyone works from dawn to dusk. Here I see one man, one woman, maybe a teenage son, and yet their farms are five times larger than a German farm.

Either they work impossibly hard or something else is happening that I don’t understand.” that something else was mechanization on a scale the Germans couldn’t comprehend the German agricultural tradition. To understand the pow shock, one must understand German agriculture in 1944. German farming was traditional, labor intensive and rooted in centuries old practices.

The typical German farm was 15 to 25 hectares, 37 to 62 acres, small by American standards. It was worked by the farmer’s family plus hired hands or seasonal labors. Harvesting was done largely by hand or with horsedrawn equipment. Grain cut with sides or horsedrawn reapers gathered into sheav by hand threshed on the barn floor with flails or small threshing machines winnowed to separate grain from chaff.

A typical German wheat harvest required 10 to 15 workers per 25 hectares 2-3 weeks of intensive labor hand tools and horsedrawn equipment physical endurance and long hours. This system had advantages. It employed many people. It required little capital investment and it was sustainable with available technology. But it was also brutally inefficient by American standards. Nazi ideology romanticized this inefficiency.

The German peasant farmer tied to his land working with his hands living according to traditional rhythms was celebrated as the embodiment of German virtue. Manual labor was noble. Sweat was honorable. The soil connection was spiritual. Hitler himself spoke of this frequently. The German farmer is the backbone of our vulk. His labor feeds the nation. His connection to the soil gives him strength.

We must preserve the German farming tradition against the mechanized soulless agriculture of the Americans. German soldiers internalized this ideology. Many came from farming families. They believed in the dignity of agricultural labor. They saw farming as requiring discipline, organization, and German thoroughess.

So when they arrived in Iowa and saw vast farms with almost no workers, they interpreted it as American laziness and poor organization. They didn’t yet understand that they were witnessing a completely different agricultural paradigm. The American agricultural revolution, machines replace muscles.

While Germany celebrated traditional farming, America had been mechanizing agriculture for decades. The transformation began in the 19th century with Cyrus McCormick’s mechanical reaper, but it accelerated dramatically in the 20th century with gasoline tractors. By 1920, tractors were replacing horses on American farms. By 1940, over 1.5 million tractors operated on US farms. They could plow, plant, and pull equipment faster and longer than any horse team.

Combine harvesters. These machines combining reaping, threshing, and winnowing in one pass revolutionized grain farming. The first successful combines appeared in the 1920s. By 1940, they were common on large wheat farms. Industrial manufacturing applied to agriculture. Companies like International Harvester, John Deere, Alice Jmers, and Massie Harris mass-produced farm equipment using assembly line techniques.

What would have been expensive custom equipment in Germany was mass-produced and relatively affordable in America. The result was astonishing productivity. German agriculture 1940s. Average wheat yield 2,000 kg per hectare labor required. 150 man hours per hectare mechanization limited to 10 to 15% of farms. American agriculture 1940s.

Average wheat yield 1,100 kg per acre, 2,720 kg per hectare. Higher yield labor required 15 man-hour per hectare. 90% less labor mechanization. 60 to 70% of farms used tractors. 40% had combines. An American farmer with a tractor and combined could farm 200 to 300 acres essentially alone.

A German farmer with traditional methods could manage perhaps 50 acres with his family. This efficiency wasn’t just technological. It was economic. American farmers could afford machinery because industrial mass production made equipment relatively cheap. Farm sizes and productivity justified capital investment credit systems allowed farmers to finance purchases fuel. Gasoline was abundant and inexpensive.

German farmers couldn’t replicate this even if they wanted to. Equipment was expensive. Farms were small making machinery less cost effective. Fuel was scarce. and Nazi ideology discouraged agricultural mechanization. Anyway, the German PS arriving in Iowa in 1944 were about to witness this disparity firsthand. The moment of truth. The engine starts. Tom Henderson’s farm outside Clarinda was typical for the region.

480 acres, primarily corn and wheat, managed by Henderson, his wife Martha, and their 17-year-old son Jim, who would be drafted within months. In Germany, a farm this size would require a permanent staff of 20 to 30 people plus seasonal workers. The Hendersons managed it with three people and a barn full of machinery.

When the camp commandant at Clarinda offered P labor, Henderson was initially reluctant. I don’t need 40 men, he told the officer. I’ve got my tractor and combine. Maybe I could use four or five to help with maintenance, but 40. Take them anyway, the officer urged. It’s good for them. Keeps them busy. teaches them about America, and you pay almost nothing. The government covers most of it.

” Henderson agreed, “More as a civic duty than from necessity.” On July 15th, 1944, 40 German PS arrived at his farm for wheat harvest. Henderson had 40 acres of winter wheat ready to cut. The Germans assembled expecting to be given sides, rakes, and organization into work teams. This was how harvesting worked in their experience.

Instead, Henderson told them to rest in the shade while he took care of it. The prisoners were confused. Curt Weber asked the interpreter, “How will he harvest 40 acres alone? Is he calling more workers?” “No,” the interpreter replied. “He’s using his combine.” “His what? You’ll see.” Henderson walked to his barn and rolled out a 1941 Alice Jmer’s allcrop harvester. To the Germans, it looked like an industrial machine, not a farm tool.

It was 12 ft wide, 15 ft long, painted bright orange with a 6-ft cutter bar, an internal threshing mechanism, and a grain hopper. Henderson climbed into the operator’s seat, started the engine. A sound like a tank motor to the former soldiers, and drove into the wheat field.

The Germans watched in stunned silence as the combine cut wheat with the headerfed into the threshing mechanism separated grain from straw cleaned the grain deposited clean grain into the hopper discharge straw and chaff out the back. All in one continuous operation at 3 mph. Hans Muller stared. He’d spent entire summers helping harvest his uncle’s wheat farm in Bavaria.

40 men working two weeks with sides, bundling sheav, hauling them to the barn, threshing on the barn floor with flails, winnowing. This machine did all of it alone in hours. By mid-afternoon, Henderson had completed 30 acres. He stopped to unload the grain hopper into a truck. 4,000 lb of clean, threshed wheat poured out in 5 minutes. Then he returned to finish the field. The 40 German PS stood idle, leaning on tools they hadn’t used.

They’d been given shovels and rakes as busy work, but it was obvious their labor was completely unnecessary. Weber turned to Mueller. We mocked him. We called him lazy. We said he lacked German discipline. Mueller nodded slowly. He doesn’t need discipline. He has that. He gestured at the combine, now completing the final rows of wheat.

Another prisoner, a former farmer from Saxony named Friedrich Ko, said quietly, “We’ve been doing it wrong for centuries. We’ve been doing it wrong. We thought hard work and many hands were virtues, but this this makes our labor worthless. By evening, Henderson had harvested all 40 acres. He shut down the combine, climbed off, and walked over to the assembled PS.

Through the interpreter, he said, “Thanks for coming out. Didn’t really need the help today, but the common dance said, “You boys should see how we do things. Tomorrow, if you want, I can show you how the corn planter works. That’s a sight, too.” The Germans returned to camp in silence.

That night, multiple PS wrote letters home describing what they’d witnessed. Camp sensors intercepted and filed them. The letters revealed a common theme: shock, humiliation, and dawning realization. We were told Americans were lazy and inefficient, wrote one prisoner. Now I understand. They’re not lazy. They just work smarter. One man with a machine does what would take 50 of us.

How are we supposed to win a war against this? The pattern repeats. mechanization everywhere. Over the following months, German PSWs across the Midwest witnessed similar scenes. Corn planting in Nebraska. PS expected to hand plant corn, dropping seeds in furrows, covering them with hose.

Instead, they watched a farmer with a four row mechanical planter cover 20 acres in a morning. The machine dug furrows, dropped seeds at precise intervals, covered them, and packed the soil all automatically. Cotton picking in Texas. German prisoners familiar with laborintensive European crops expected armies of workers handpicking cotton.

They saw mechanical pickers, massive machines that stripped cotton from bowls faster than 50 handpickers. Dairy farming in Wisconsin, PS dairy farms expected to milk cows by hand, the method still common in Germany. They discovered mechanical milking machines. One farmer with four milking machines could milk 100 cows in the time it took 10 men to milk by hand. irrigation in California. Germans expected to see manual irrigation, men with buckets and ditches, laboriously watering crops.

They saw pivot irrigation systems, motorized pumps, and vast networks of pipes that delivered water without human labor. Every instance reinforced the same message. American agriculture had moved beyond manual labor. Machines had replaced muscles. Capital had replaced labor.

One American farmer produced what 10 German farmers produced and did it with a fraction of the effort. The productivity statistics were staggering. Wheat production per farmer. Germany 5 to 6 tons per year per farmer USA 75 to 100 tons per year per farmer. Corn production per farmer. Germany 8 to 10 tons per year per farmer. USA 150 to 200 tons per year per farmer.

Labor efficiency Germany 80% of rural population engaged in agriculture USA 18% of population produced food surplus for domestic use and export. The PS were witnessing why Germany could never win a war of production against America. The same mechanization, capital investment and industrial efficiency that built 49,000 Sherman tanks applied to agriculture. America didn’t just outproduce Germany in weapons.

It outproduced Germany in everything. From mockery to respect, the realization didn’t happen instantly. Many PS initially rejected what they’d seen. It’s wasteful, some argued, using expensive machines when men could do the work. What happens to all the workers who lose their jobs? But over time, the evidence became undeniable.

Hans Mueller spent 6 months working on various Iowa farms. He saw tractors plowing fields in days that would take German farmers weeks. He saw combines harvesting hundreds of acres. He saw grain elevators storing thousands of tons. He saw trucks hauling produce to markets hundreds of miles away.

In November 1944, he wrote a letter to his wife that camp sensors noted as indicative of changed attitude. Liba Margaret, I must tell you something that will sound like treason, but it is truth. We were lied to about America. The propaganda told us Americans were weak, decadent, inefficient. This is false. The Americans are the most efficient people on Earth. They don’t work harder, they work smarter.

One American farmer produces more than 10 German farmers, not through longer hours, but through better tools. I begin to understand why we lost the war. We were fighting an enemy whose farmers alone could outproduce our entire economy. Their factories, their fields, their mines, everything operates with a level of mechanization we never achieved.

They didn’t defeat us through courage or numbers. They buried us under an avalanche of production. When I return, if I return, we must learn from this. The old ways, hand labor, traditional methods, pride in sweat, these are not enough in the modern world. The Americans have shown a better way. Curt Weber had a similar transformation. Initially defensive and proud, he spent months working on Nebraska wheat farms.

By spring 1945, he was asking farmers to explain how their machinery worked, how they financed it, how they maintained it. “I’m learning more here than I ever did in school,” he wrote to a friend. “These American farmers are teachers, whether they know it or not. They’re showing us the future of agriculture.

When this war ends, Germany must modernize or be left behind permanently.” Not all PS underwent this transformation. Some remained bitter, attributing American productivity to stolen wealth or Jewish conspiracies. But US intelligence officers tracking POW attitudes noted a significant shift by late 1944.

A report from Camp Clarinda stated, “German P attitudes toward American agriculture have evolved from mockery and superiority to respect and interest. Many prisoners now express desire to learn American farming methods. This represents a positive development in re-education efforts. The US government had indeed been conducting subtle re-education.

PS were shown documentary films, given American newspapers, and exposed to American life. The goal was to dnazify them and prepare them for return to a democratic Germany. But no propaganda film was as effective as standing in an Iowa wheat field watching one man with a combine do the work of 50. That experience taught what lectures never could.

that democracy and capitalism, whatever their flaws, produced a level of prosperity and efficiency that fascism couldn’t match. Why Germany lost? By 1945, as the war in Europe ended and PS awaited repatriation, many had come to a broader understanding.

They’d lost the war not because German soldiers weren’t brave or skilled. They were both. Not because German tactics were inferior. Often they were superior. They’d lost because they were fighting an enemy whose entire economy operated at a level Germany couldn’t approach. The mechanized farms were just one example. PS working in other sectors saw similar patterns. Mining.

German prisoners in Montana copper mines saw mechanization that extracted 10 times what manual labor could. Forestry PS in Oregon watched power saws and mechanical loaders do the work of hundreds of men with axes. Manufacturing. Those assigned to factory work saw assembly lines producing goods at rates impossible in German factories. Everywhere the same lesson.

American industry had achieved efficiency through capital investment, mechanization, standardization, and mass production. Germany had focused on craftsmanship, quality, and intensive labor. German tanks were better than American tanks individually. But America built 10 tanks for every German one. German farms were managed more carefully. Each hectare tended with precision.

But American farms produced three times more per hectare with 1/10enth the labor. This wasn’t about national character or racial superiority, the Nazi explanation for everything. This was about industrial organization and economic systems.

Capitalism with all its chaos and inequality had produced an economy that could outproduce any planned economy or traditional system. Democracy with all its messiness and debate had mobilized resources more effectively than dictatorship. Friedrich Ko the Saxon farmer who’d watched Tom Henderson’s combine in stunn silence wrote perhaps the most perceptive analysis. We were told that strength came from unity, discipline, and will. That German thorowness and organization would overcome any obstacle.

But we confused means with ends. We took pride in hard work as if labor itself was the goal. The Americans understood that the goal is production and labor is merely one means, often an inefficient means. To that end, they replaced labor with capital wherever possible. They invested in machines, infrastructure, technology.

They standardized everything to achieve economies of scale. They trusted individuals to make decisions rather than imposing rigid hierarchies. The result, one American farmer outproduces 10 German farmers. One American factory worker outproduces five German workers.

One American economy outproduces all of Germany and its conquered territories combined. We never had a chance. We were fighting a 19th century war against a 20th century economy. The return home. Most German PS returned home between 1946 and 1948. They found a Germany destroyed, cities in ruins, industry shattered, agriculture disrupted. Many who’d worked on American farms tried to apply what they’d learned.

Hans Mueller returned to Bavaria and using American aid money bought a small tractor, the first in his village. His neighbors mocked him for American ideas, but within 3 years he tripled his productivity. By 1955, half the farmers in his region owned tractors. Kurt Weber returned to a farm in what became East Germany.

He tried to implement American methods, but found them impossible under Soviet collectivization. He eventually fled to West Germany in 1953 where he became an agricultural adviser teaching mechanization techniques. Friedrich Ko returned to Saxony Soviet zone and kept his American experiences to himself. In private letters discovered after German reunification, he expressed frustration.

I’ve seen the future of agriculture and it works, but we’re not allowed to implement it. We’re told that socialist collective farming is superior. It isn’t. I’ve seen American farms. They produce three times what we do with one-third the workers. But speaking such truth is dangerous. In West Germany, Marshall Plan aid included funding for agricultural mechanization.

American tractors, combines, and other equipment flowed into the country. Agricultural advisers taught American methods. By 1960, West German agriculture had modernized significantly, productivity had soared, and rural living standards had risen dramatically. In East Germany, agriculture remained collectivized and labor intensive. Productivity lagged far behind the West.

The contrast became another symbol of the systemic differences between capitalism and communism. Some former PS remained bitter. They attributed American productivity to size, resources, and unfair advantages rather than systemic superiority, but many underwent genuine transformation. A 1960 survey of former PS who’d worked on American farms found 73% reported positive or very positive views of American agriculture. 68% said the experience changed their view of America generally.

54% said it influenced their support for democracy and market economics. 82% said American farms were more efficient than German farms. The experience of watching one farmer with a combined harvest 40 acres. That moment of humiliation and revelation had lasting impact. Mechanization and modernity. The story of German PS and American combines is more than an anecdote.

It illuminates fundamental questions about why World War II ended as it did. Germany bet on traditional virtues. Discipline, sacrifice, manual labor, marshall prowess. These virtues weren’t worthless. German soldiers fought with extraordinary skill and courage. But America bet on different virtues.

Innovation, efficiency, capital investment, mechanization, mass production. These virtues proved decisive. The war wasn’t won primarily on battlefields. It was won in factories, oil fields, and wheat fields. It was won by economic systems that could produce overwhelming material superiority.

One American farmer with a combined harvester represented the entire logic of American victory. Replace muscle with machine. invest capital to save labor, prioritize efficiency over tradition, embrace change over continuity. This philosophy built the tanks, ships, planes, and bombs that defeated Germany.

But it also built the combines, tractors, and trucks that fed the Allied armies and civilian populations. The German PS watching Tom Henderson harvest 40 acres in an afternoon witnessed the death of one worldview and the triumph of another. They believed that strength came from will, discipline, and sacrifice. They learned that strength comes from productivity, innovation, and efficiency.

They believed that manual labor and traditional methods were virtuous. They learned that these are merely tools and inferior tools should be discarded. They believed that Germany’s organized, disciplined approach to everything, including farming, was superior to American chaos and individualism.

They learned that American chaos was actually decentralized innovation and American individualism was actually entrepreneurial efficiency. The lesson was humbling for men who’d believed in German superiority, racial, cultural, organizational. Watching an Iowa farmer casually outperform 50 German workers was crushing, but it was also educational. And for those willing to learn, it offered a path forward.

The lazy farmer’s final lesson. Tom Henderson never knew the impact his combine harvester had on the 40 German PS who watched him that July day in 1944. He was just a farmer doing his job. The machine was just a tool he bought to make his work easier. He wasn’t making a political statement or demonstrating American superiority. He was harvesting wheat. But to the Germans watching, it was an earthquake.

Everything they believed about American laziness, inefficiency, and weakness crumbled as the combine ate the wheat field. The mockery died in their throats. The jokes about undisiplined Americans evaporated. The confidence that German methods were superior disappeared. In its place came a new understanding.

They’d lost the war long before the first shot was fired. They’d lost it when America embraced mechanization and Germany clung to tradition. When America invested in capital and Germany relied on labor, when America standardized production and Germany fetishized craftsmanship, the war was decided not by generals but by farmers with combines, factory workers with assembly lines, oil workers with derks and engineers with mass production blueprints.

Germany brought discipline, courage, and sophisticated tactics. America brought machines, abundance, and overwhelming productivity. Discipline can’t defeat abundance. Courage can’t defeat machinery. Sophistication can’t defeat mass production. The lazy American farmer who climbed into his combine and casually harvested 40 acres taught this lesson more effectively than any battlefield defeat ever could.

And 40 German PS standing idle with their useless shovels. Learned what their generals and leaders refused to admit. Germany never had a chance. The combined harvester didn’t just harvest wheat. It harvested illusions, destroyed propaganda, and planted seeds of a new understanding. When those PS returned home, some brought those seeds with them.

They would help grow a new Germany, democratic, mechanized, prosperous. The lazy farmer had started his engine. And in doing so, he’d finished something the war had begun, the destruction of the myth of German superiority. The combine rolled forward. The wheat disappeared into its mechanisms, and German mockery ended in an Iowa field under a summer

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load