The Americans didn’t hear them, didn’t see them, didn’t sense them. Four MV SOG operators crouched in the undergrowth along a trail junction in Fuak Twi province had been watching this stretch of jungle for 3 hours. They knew every sound, the rhythm of the canopy dripping, the distant call of a barking deer, the way the wind moved through the elephant grass.

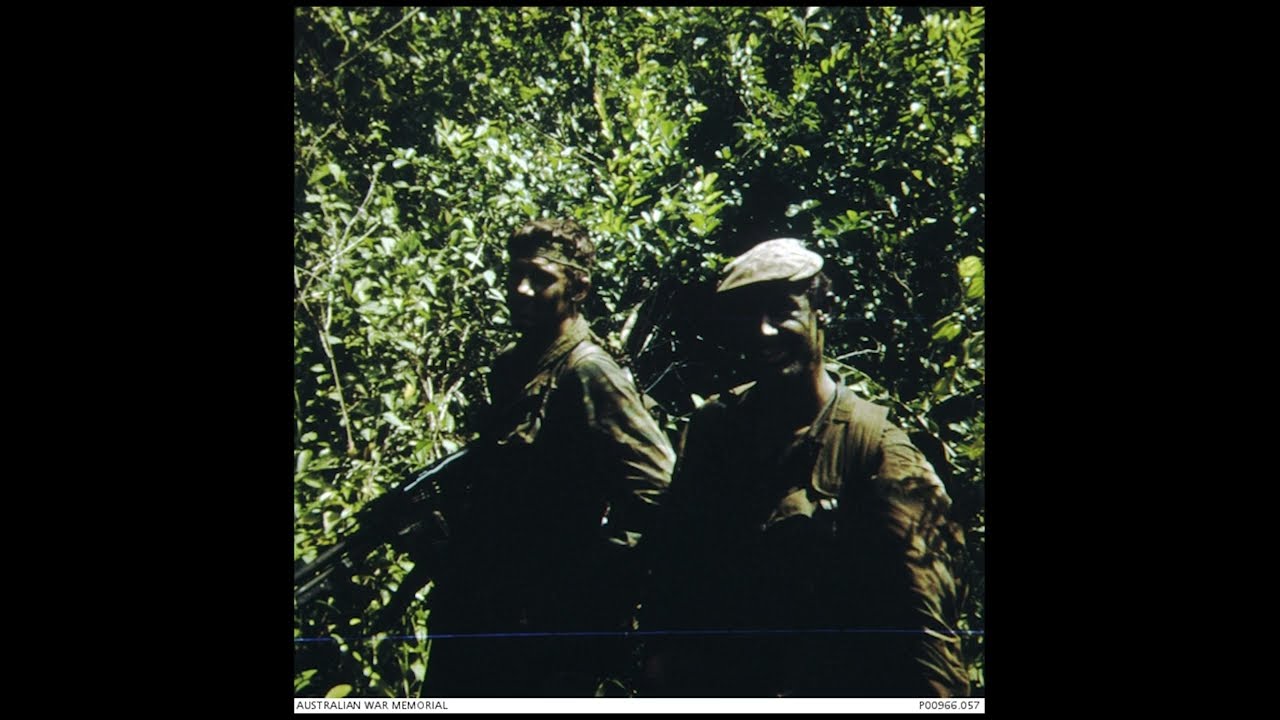

And then without warning, four men passed within 15 m of their position. Australian SAS moving like smoke through the trees. No snapping branches, no disturbed foliage, no metallic clink of equipment. Just four silent figures gliding through terrain so thick you could barely see 10 m ahead. And they moved through it like they’d been born there.

The SOG team leader, a veteran of two tours and dozens of crossber operations, would later say, “For the first time, Mac Vogg realized someone else knew this jungle better.” To understand why this moment shattered assumptions, you need to understand who these men were. M V So SOG Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Studies and Observations Group. The name was a deliberate misdirection.

They weren’t studying anything. They were running the most classified, most dangerous reconnaissance operations of the entire war. Crossber missions into Laos and Cambodia. Hunter killer teams tracking NVA regiments. Men who inserted by helicopter into areas so hostile that extraction wasn’t guaranteed. These weren’t regular infantry.

These were America’s best green berets, force recon marines, Navy Seals handpicked for a war within the war. And then there was the Australian SAS. Fewer men, quieter operations built from a different doctrine entirely. While American special forces had been shaped by World War II, Korea, and counterinsurgency theory, the Australian SAS had been forged in the Malayan emergency.

A brutal 12-year jungle war against communist insurgents where patience, silence, and tracking skills meant the difference between life and death. The Australians brought something to Vietnam that couldn’t be taught in a training manual. Generational bushcraft. men who’d grown up in the outback, who’d learned to track from indigenous Australians, who understood that the jungle wasn’t an obstacle, it was an ally if you knew how to move through it.

These two units rarely crossed paths, different areas of operation, different command structures, different missions. But when they did meet, everything changed. Picture it. Dense triple canopy jungle. Humidity so thick it clings to your skin like a second uniform. Every breath tastes like rot and wet earth. Visibility may be 10, 15 m on a good day. Sound carries strange in this environment.

A footstep 100 m away can sound like it’s right beside you. Or you can miss a patrol passing 3 m from your position if they know what they’re doing. The SOG team had been inserted the night before. Standard recon patrol. Observe. Report. Avoid contact. They’d found a good position overlooking a trail junction that intelligence suggested was being used for NVA resupply.

They were expecting enemy movement. They weren’t expecting allies. The first man appeared like a ghost materializing from the green wall of vegetation. No sound preceded him. No rustle of leaves, no crack of a twig. He simply was already in the open, rifle low, eyes scanning, moving with a fluidity that seemed impossible given the terrain. Then the second man, then the third and fourth. Fourman patrol.

Standard SAS brick moving in a loose diamond formation. Each man positioned to cover a different ark. Each man separated by enough distance that a burst of fire couldn’t take more than one. The SOG team leader froze, hand signal to his men. Freeze, friendlies, observe.

If you served in Vietnam, you know the sound of a careless patrol, the clink of dog tags, the slush of water in a canteen, the distinctive metallic scrape of an M16 sling swivel catching on webbing, the heavy thud of boots hitting Earth. This wasn’t that. This was something else entirely. The Australians moved like water, finding the path of least resistance. Each footstep deliberate heel toe.

Weight distributed, testing the ground before committing. No straight lines. They flowed around obstacles rather than pushing through them. Their eyes weren’t just forward. They were reading the jungle at multiple levels simultaneously. canopy, ground, middle distance, constantly scanning for disturbance, for sign, for threat, and then they were gone. The jungle swallowed them as completely as it had revealed them.

Within seconds, the SOG team couldn’t hear them anymore, couldn’t track their movement. It was as if they’d never been there. The team leader keyed his radio quiet, controlled, professional. But underneath there was something else in his voice. Confusion, respect, and the first stirring of a question that would reshape how MV SOG thought about jungle warfare.

How the hell did they do that? That night, after extraction, the SOG team compared notes at their forward operating base. Did you see their gear? No helmets, just soft bush hats, no clanking, nothing metal touching metal. Their packs lighter than ours, way lighter. Did you see how they walked the trail? The details started adding up.

Each observation building into a larger picture. The Australians weren’t wearing standard issue anything. Their webbing was different canvas and cloth, not the metal clipped American gear that could rattle if you moved wrong. No steel helmets, no heavy rucks sacks loaded with days of supplies, just lightweight patrol packs, efficiently packed, weight distributed close to the body. Their weapons were different, too.

Many carried the L1A1 SLR, the British variant of the FN FAL, but modified, lightened with tape wrapped around potential noise points. Some carried shortened versions. Everything about their kit screamed one philosophy, silence over firepower, mobility over protection. But it was the way they moved that stuck with the Americans.

One of the SOG operators, a former tracker from Montana who prided himself on his fieldcraft, put it simply. They weren’t just walking through the jungle. They were reading it every step. Like they could see things we couldn’t. It wasn’t magic. It was training. It was doctrine. It was culture.

The Australian SAS had learned their craft in Malaya, where the enemy could disappear into villages where tracks might be days old, where patience mattered more than aggression. They’d been taught by men who’d fought that war, who’d learned from the Ebon trackers of Borneo, who’d absorbed the lessons of jungle warfare over years of brutal experience.

Many of them had grown up in the Australian bush. They’d learned to track as kids, reading animal signs, understanding how vegetation recovered from disturbance. knowing the difference between an old track and a fresh one. Some had trained alongside indigenous Australians who could follow a trail across rock. And they’d brought all of that to Vietnam.

The question forming in the minds of M VOG wasn’t just tactical curiosity. It was professional necessity. Why did the SAS move through the jungle as if it belonged to them while Americans felt like visitors? The answer would force M. Vogg to reconsider everything they thought they knew about reconnaissance.

The difference wasn’t about who was tougher. Both units were comprised of the hardest men their nations could produce. Men who’d passed selection courses designed to break them. Men who’d proven themselves in combat. The difference was philosophy. The Australian SAS operated from a set of principles developed in Malaya and refined in Borneo. Their doctrine was simple but unforgiving. Never be seen.

Never be heard. Never leave sign. Ultra small teams, usually four men, sometimes fewer. The smaller the team, the quieter the movement, the less likely to be compromised. They patrolled slowly, deliberately, with agonizing patience. A four-man SAS patrol might cover less ground in a day than a larger unit could in 2 hours, but they’d see everything, hear everything, and leave nothing behind. Their mission priority was clear. Observe and report.

If compromise happened, Xfiltration took priority over engagement. One shot meant the mission was over. Better to break contact silently, evade, and live to patrol another day than to win a firefight, but lose the ability to operate in that area again. This was tracking based thinking. The jungle wasn’t an obstacle course to be conquered.

It was a book to be read, every broken twig, every disturbed leaf, every footprint in soft earth. The SAS trained their men to see patterns to understand how terrain chneled movement to predict where the enemy would be based on sign that was hours or even days old. Mac Vogg operated from a different playbook.

Their missions were high risk, high payoff, deep reconnaissance, crossber insertions into denied territory, trail watching on the Ho Chi Min Trail, wire taps on enemy communication lines, prisoner snatches. These weren’t observe and report missions. These were kinetic operations in the enemy’s backyard, where violence of action often meant the difference between success and catastrophe.

SOG teams were larger, usually composed of two or three American green berets leading a squad of indigenous fighters, montine yards or Vietnamese. They moved with purpose and speed. When they hit, they hit hard. When they broke contact, they did it with overwhelming firepower, claymores, grenades, rifle fire, creating enough chaos to escape while the enemy was still reacting.

Their doctrine came from American military tradition, aggression, firepower, and audacity. It had worked in World War II. It had worked in Korea. And in the early years of Vietnam, it worked for SOG, too. But meeting the SAS revealed something uncomfortable. There was another way, a quieter way.

A way that didn’t rely on firepower to solve problems because problems were avoided before they started. Every digger knows you don’t win a jungle fight by being the first to shoot. You win by not being seen. That principle, that simple unforgiving principle was about to teach M. V. SOG something they hadn’t learned in any training course.

To truly understand what M V so witnessed, you have to go back to 1948, back to Malaya, back to a different jungle war that most people have forgotten, but that shaped everything. the Australian SAS would become. The Malayan emergency wasn’t called a war couldn’t be for insurance and political reasons, but it was every bit as brutal as Vietnam would later prove to be.

Communist insurgents, the Malayan National Liberation Army, had disappeared into the jungle. They lived there. They knew it. They owned it. The British tried conventional approaches first. Large patrols sweeping through the jungle. search and destroy operations with company-sized elements. It didn’t work. The communists would hear them coming from kilometers away.

The sound of a hundred men moving through dense vegetation carries like thunder. The insurgents would fade deeper into the green, wait for the British to exhaust themselves, then reappear somewhere else entirely. The jungle was winning. Then someone had a different idea. What if instead of trying to dominate the jungle with force, you learned to live in it? What if you became as quiet, as patient, as invisible as the enemy? The British SAS pioneered the approach.

Small patrols, four men, sometimes fewer, living in the jungle for weeks at a time. No large base camps that could be heard or smelled or spotted from the air. Just men moving slowly through the green hell, gathering intelligence, building trust with the indigenous population, and when the time was right, striking with surgical precision. They learned from everyone who knew the jungle better than they did.

The Ebon trackers of Borneo indigenous people who could follow a three-day old trail across solid rock who could tell you how many men had passed and whether they were carrying loads by examining a single bent leaf. They could smell a camp from half a kilometer away could hear the difference between a gibbon moving through the canopy and a man trying to move quietly. The British SAS absorbed this knowledge like sponges.

They spent months living with the Ebon, learning their techniques, understanding that tracking wasn’t just about following footprints. It was about reading the entire environment. How vegetation recovered from disturbance. How different soils held impressions. How the angle of broken branches indicated direction of travel. How the behavior of animals revealed human presence.

They learned that in the jungle, patience wasn’t just a virtue. It was survival itself. A British SAS patrol in Malaya might spend two weeks tracking a single communist cell. Not rushing, not trying to close distance quickly, just following methodically, gathering information, understanding patterns. Where did they get water? Where did they sleep? What roots did they use? Who supplied them? And then when the intelligence was complete, they’d either call in larger forces or conduct a precision raid themselves. Quick, violent, over in seconds, then disappear

back into the jungle before reinforcements could arrive. By the time the emergency ended in 1960, they developed a complete doctrine. Every aspect of jungle warfare had been analyzed, tested, refined. The patrol techniques, the equipment, the mindset, all of it paid for in British blood. Learned through 12 years of hard combat.

When Australia decided to raise its own SAS squadron in 1957, they sent their best men to Malaya to learn from the British. Those founding members, the men who would build the Australian SAS, trained with British veterans, patrolled with them, absorbed every lesson that had been written in blood on jungle trails. But the Australians added something uniquely their own.

They brought their bush knowledge, their understanding of harsh, unforgiving terrain. Many of these founding members had grown up in the outback places where the nearest neighbor might be 50 km away where summer temperatures could hit 50° C where you learn to be resourceful because help wasn’t coming. They understood isolation. They understood self-reliance.

They understood reading terrain for water, for shelter, for danger. They combined British jungle warfare doctrine with Australian bushcraft. And the result was something special, something that would prove itself in Borneo during the Indonesian confrontation and then definitively in Vietnam.

The Australian SAS that deployed to Puaktui province in 1966 wasn’t just carrying on British traditions. They were the culmination of nearly two decades of continuous jungle warfare experience, refined through Australian innovation and tested in some of the harshest environments on Earth. That’s what Mac V SOG saw that day.

Not just four men moving through the jungle, but the end product of a long evolution. Decades of learning, hundreds of patrols, thousands of hours moving through terrain that could kill you as readily as any enemy. The Americans were seeing mastery and they had the professional wisdom to recognize it. If you’ve ever worn military gear in the jungle, you know everything matters.

The weight of your pack determines how far you can patrol before exhaustion sets in. The way your webbing sits on your hips determines whether you’ll have bruises and raw spots after 8 hours of movement. Whether your canteen cap is properly tightened determines whether you’ll give away your position with a metallic rattle.

Whether your rifle sling has a metal clip that can catch on vegetation determines whether you’ll sound like a walking hardware store or move in silence. Every single piece of equipment is either helping you survive or betraying your position with every step. The Americans came to Vietnam with gear designed for conventional warfare in Europe or Korea.

M1 steel helmets protective against shrapnel. Yes, but heavy in Vietnam’s humidity. That weight became oppressive after hours of patrolling. The helmet sat on your head like an oven, trapping heat, causing headaches, and worst of all, it caught light. The distinctive ping of something striking a steel helmet, a branch, a piece of falling debris could be heard 50 m away in quiet jungle.

Standardiss issue webbing with metal D-rings, clips, and fasteners. The American system was robust, designed for carrying heavy loads in combat, but it was noisy. Metal onmetal contact hardware that rattled if not secured perfectly. Under the stress of patrol, with sweat making everything slippery, with fatigue setting in, discipline could slip.

One loose clip could compromise an entire mission. Canvas rock sacks designed to carry everything a soldier might need for extended operations. Sea rations for 5 days. Extra ammunition 200 rounds or more. Batteries for radios. Signal panels. Spare clothing. First aid supplies. The result? 60 to 80 lb of gear on your back.

That weight had consequences. It slowed you down. It fatigued you faster in the heat. It made you clumsy when you’re carrying that much weight. You can’t step as carefully. You push through vegetation rather than moving around it. You make noise. Standard issue cantens that sloshed if not completely full. Dog tags that jangled unless taped together.

Metal ammunition clips that clicked against each other in magazine pouches. All the small sounds that added up to a symphony of noise that announced your presence to anyone listening. The Australians had stripped all of that away.

Their webbing was based on the British 58 pattern canvas pouches attached to a belt and yolk system with minimal metal hardware. Everything was designed to be quiet. Buckles were covered. Potential noise points were wrapped in cloth or tape. The system sat close to the body, distributed weight efficiently, and most importantly, could be worn for hours without generating sound. No steel helmets.

The SAS wore soft bush hats or wide-brimmed boony hats practical for keeping sun and rain off quiet and critically they didn’t reflect light. Some troopers went bare-headed, relying on the jungle canopy for cover. The choice was personal based on the mission and the terrain, but the philosophy was universal.

Protection was less important than stealth. Their packs were smaller, lightweight patrol packs designed to carry just what you needed for the mission. Usually 3 to 5 days of rations maximum, minimal spare clothing, essential equipment only, 30 to 40 lb total weight. Some patrols went even lighter. The philosophy was simple. Carry less, move better, survive longer.

They didn’t carry as much ammunition because their doctrine didn’t rely on firefights. If you compromised a patrol by getting into a gunfight, you’d failed. better to carry less weight and retain the ability to move silently than to be heavily armed and loud. Their weapons reflected this too.

The L1A1 SLR was reliable and accurate, but the Australians modified them ruthlessly. Tape around the fortock to prevent wood creaking. Slings adjusted so the weapon rode secure against the body without bouncing. Some carried shortened versions for easier movement through thick vegetation. Everything that could make noise was addressed.

Metal parts that might contact each other were separated with fabric. Ammunition pouches were packed tight so magazines couldn’t rattle. Equipment was secured with dummy cord so nothing could fall and clatter against rocks or metal. Even their boots were different, though both nations used variations of jungle boots with canvas uppers and rubber soles.

The Australians preferred lighter models with thinner soles because they understood something crucial. Your feet are sensors. You need to feel the ground to know if you’re about to step on something that will crack or rustle. Thick soles provided protection but reduced sensitivity. And socks, something so mundane it seems trivial, became critical.

The Australians changed socks religiously, sometimes twice a day if they’d crossed water. They powdered their feet every chance they got. They understood that foot rot could compromise a patrol as effectively as enemy fire. An infected foot meant slower movement, more noise, reduced combat effectiveness. Everything was about noise discipline, about weight management, about understanding that in the jungle less was more.

One SOG operator who later trained with the SAS described picking up an Australian patrol pack and being shocked at how light it was. I asked him where the rest of his gear was. He smiled and said, “This is it, mate. Everything I need and nothing I don’t.” That was the difference right there. That was the Americans had been conditioned to carry everything they might possibly need.

The Australians carried exactly what they would actually use. It sounds like a small distinction, but it changed everything about how you moved, how long you could patrol, how quietly you could operate. This wasn’t just gear preference. This was philosophy made manifest in equipment selection. We were dressed for a fight.

One SOG veteran later reflected, “They were dressed to never be found.” This is where the Australian SAS truly distinguished themselves. Where their unique combination of cultural background, training, and experience created a capability that was nearly impossible to replicate. Tracking, not just following obvious trails, not just noticing disturbed vegetation or clear footprints in mud.

True tracking, the ability to read sign, so subtle that most soldiers would walk right past it, to reconstruct movement from fragments of evidence to predict where someone had gone and where they would be based on the faintest of clues. This skill more than any other defined SAS advantage in Vietnam. It came from multiple sources, each contributing to a complete skill set. First, the Australian upbringing.

Many SAS troopers had grown up in rural areas in the bush where tracking was practical knowledge passed down through generations. As kids, they’d learned to spot kangaroo tracks across hard ground, to follow feral pigs through scrub, to find lost livestock by reading sign. They’d learned which way animals traveled to water, how they moved through terrain, what signs they left behind.

This wasn’t formal military training. It was childhood education absorbed naturally through years of living in the Australian bush. By the time these men enlisted, they already had a foundation that most soldiers from urban backgrounds simply didn’t possess. Second, indigenous influence.

This is where Australian tracking capability became truly exceptional. Aboriginal and Torres straight islander peoples had been tracking across the Australian continent for more than 60,000 years. Their skills had been refined through countless generations, developed to a level of sophistication that seemed almost supernatural to outsiders. They could follow tracks across solid rock by noticing the faint scratch marks left by pebbles caught in boot treads.

They could determine the age of a footprint by the way dust had settled into it, by whether dew had formed in the depression, by how insects had interacted with the disturbed soil. They could tell you not just how many people had passed, but whether they were tired, whether they were carrying loads, whether they were running or walking. The Australian military slowly and sometimes reluctantly had learned to incorporate this indigenous knowledge.

Aboriginal trackers had served with Australian forces since World War I, and their contributions had been invaluable. Some SAS candidates were fortunate enough to train directly with indigenous trackers during their selection and continuation training. Learning techniques that couldn’t be found in any manual, they learned to see the invisible. A blade of grass bent against its natural growth pattern. Someone had brushed past it.

A rock slightly displaced from its depression in the soil. Someone had stepped on it. Spiderwebs broken in a pattern. something man-sized had moved through them. The faint smell of cigarette smoke or cooked rice carried on the wind humans upwind. Third, the Malayan inheritance. The British SAS had learned from the Iban trackers in Borneo during the Malayan emergency, and they’d passed that knowledge to the Australians.

The Iban could follow trails that seemed impossible tracks, days old, through dense jungle, across streams, over rock faces. They understood that tracking was holistic, involving all the senses and an almost intuitive understanding of how humans moved through terrain. The Australians combined all of these influences, bush upbringing, indigenous techniques, Malayan doctrine into a comprehensive tracking capability.

By the time they arrived in Vietnam, SAS trackers could do things that seemed impossible to observers. They could age a footprint with remarkable accuracy. A fresh print would have sharp edges. The soil still slightly moist if the ground was damp. No insect activity. After an hour, the edges would begin to dry and crumble slightly.

After several hours, insects would start to explore the depression. After a day, the print would be noticeably weathered, vegetation beginning to recover. An experience tracker could narrow the age down to within a few hours. They could differentiate between individuals and units. NVA regulars wore different footwear than local Vietkong, often Ho Chi Min sandals cut from old tires with distinctive tread patterns.

The weight distribution in footprints could indicate whether someone was carrying heavy loads. The depth and spacing could suggest whether they were moving quickly or cautiously. The number of distinct prints could reveal unit size. They could track across difficult terrain. Hard ground that seemed to leave no sign would still show evidence to a trained eye.

Displaced pebbles, scratches on rock, disturbed lyken, or moss. Water didn’t erase tracks as completely as people thought. Mud disturbed underwater settled differently than undisturbed mud, creating subtle color variations. Even after rain, certain signs remained broken branches, disturbed leaf litter compressed below the surface layer. They understood animal indicators.

Birds that suddenly went silent or alarm called indicated human presence. Monkeys that fled in a particular direction revealed movement below them. Disturbed ant colonies, broken termite highways, scattered insects, all indicated recent passage. Most importantly, they could anticipate and predict. Good trackers didn’t just follow.

They understood terrain and how it channeled movement. They knew where water sources were, where the easiest paths existed, where someone would naturally go. They could cut sign ahead of their quarry, set ambushes, intercept. Every SAS patrol included at least one dedicated scout, often two.

The lead scout walked point, reading the jungle constantly, alert for sign, for ambush indicators for anything out of place. The second scout would often confirm findings, providing a redundancy that reduced the chance of missing critical information. The rest of the patrol protected the scouts, moved at their pace, trusted their judgment absolutely.

If the scouts stopped, everyone stopped. If the scout indicated danger, the patrol reacted immediately. There was no questioning, no debate. The scouts reading of the terrain was trusted completely. This created a patrol dynamic that was fundamentally different from American operations. SAS patrols were built around the scouts ability to read terrain.

Everything else, security, communications, command, was structured to support that primary function. and it worked with devastating effectiveness. SAS patrols could follow NVA units for days, mapping their routes, identifying their bases, calling in air strikes when the opportunity was right.

They could find supply caches that aerial reconnaissance missed entirely. They could distinguish between active trails and abandoned ones at a glance. They could predict enemy movement patterns and position themselves accordingly. The intelligence they gathered was extraordinarily detailed.

Not just enemy activity in grid square, but 12 NVA regulars heavily loaded with supplies moving northeast at approximately 2 km hour. Trail shows signs of regular use, likely a supply route to a base camp estimated to be 5 to 8 km ahead. Based on terrain analysis, that level of detail made a real difference. Artillery strikes could be planned with precision. Ambushes could be positioned perfectly.

Larger operations could be timed to catch the enemy when and where they were most vulnerable. American advisers who worked with the SAS came away shaken by what they’d witnessed. One wrote in his afteraction report, “The Australians weren’t moving through the jungle. They were reading it like a book. Every broken twig, every disturbed leaf, every faint depression in the soil told them a story.

We were operating in the same environment, but they were seeing a completely different world. That capability, that uniquely Australian combination of bushcraft, indigenous knowledge, and refined doctrine gave them an advantage that couldn’t be easily replicated. But M. VOG, to their credit, recognized excellence when they saw it and began trying to learn.

The second encounter happened 3 weeks after the first. This time, it was planned. Word had filtered up through channels that an American recon team would be observing an Australian SAS patrol in operation. Not interfering, not participating, just watching and learning. The kind of quiet professional knowledge exchange that happens between elite units who respect each other’s capabilities.

The SOG team was inserted before dawn by helicopter dropped on a ridge line overlooking a river valley that intelligence indicated was being used as an NVA infiltration route. They moved to a position that provided good observation, camouflaged themselves thoroughly, and settled in to wait. The heat built as the sun climbed. The humidity became oppressive.

The air so thick with moisture that breathing felt like drowning. Sweat soaked through uniforms within an hour. Leeches found exposed skin and began feeding. Mosquitoes swarmed in clouds and the jungle was loud, a constant symphony of insect sounds, bird calls, the rustle of small animals moving through the undergrowth. The SAS patrol appeared 2 hours after first light.

Four men, same diamond formation the SOG team had seen before, moving along the valley floor with that fluid silence that still seemed impossible given the terrain. But this time, positioned above them with good sight lines, the Americans were able to watch the entire evolution unfold.

What they saw was a masterclass in jungle patrolling. The SAS scout was in the lead, moving with careful deliberation. Every few steps, he would pause, scan the terrain ahead, check the ground, look for sign. His head moved constantly, not just forward, but up into the canopy, down to the ground, side to side, checking flanks.

He was reading the entire environment, processing multiple inputs simultaneously. Then he stopped completely. Hands signal back to his patrol. Halt something here. The other three men froze midstep, perfectly still, weapons ready, but not raised to shoulders yet. No bunching up. Each man covered a different ark, creating a defensive posture that could respond to threats from any direction.

The scout crouched, examining something on the ground. from the ridgeel line, even with binoculars. The SOG team couldn’t see what he’d found, but they watched him trace something with his finger. Look ahead along the trail, signal back again. Enemy sign, recent, and then the stalk began.

What followed over the next 6 hours was a demonstration of patience that was almost painful to watch for men trained in American doctrine. The scout moved forward maybe 5 m. then stopped, scanned, listened, checked the wind direction by wetting a finger and holding it up, looked for more sign, signaled back to his patrol, moved forward another few meters. The pace was agonizing.

At this rate, they’d cover perhaps a kilometer in an entire day. Every instinct in the watching Americans wanted them to move faster, to close distance, to make something happen. But the Australians knew something. The Americans were just beginning to understand. In the jungle, speed kills you.

The man who moves quickly is the man who steps on the trip wire he didn’t see. who walks into the ambush because he was looking ahead instead of reading the ground. Who makes enough noise that the enemy hears him coming and disappears before he arrives. The man who moves slowly, who reads every sign, who watches constantly. He survives. He sees the enemy first. He chooses when and where to engage, if at all.

The temperature climbed into the mid90s. The humidity had to be near 100%. Rain started falling around midday. Not the heavy monsoon downpours, but steady soaking rain that turned everything to mud and reduced visibility even further. The SAS patrol didn’t speed up, didn’t change their methodology.

They just kept moving with that same methodical patience, reading sign, confirming findings, adjusting their path based on what the scout was seeing. No talking, not even whispers. Communication happened entirely through hand signals. Economical gestures practiced so many times that each man knew instantly what the others meant. A raised fist. Halt. Two fingers pointing at eyes. Then forward. I see something.

A hand slicing across throat. Danger close. The spacing was perfect. Each man moved when the man in front of him was set and providing cover. They never bunched up, never created a target that could be taken by a single burst of fire. Even when they halted, they maintained separation. Each man finding cover, each man responsible for his own security while contributing to the patrol’s overall defensive posture.

Around midday, the scout found something significant. He signaled back. Fresh sign. Multiple individuals moving recently. The patrol melted into the vegetation. One moment they were visible, the next they’d simply vanished into the jungle. The Americans watching from above and knowing exactly where they were, could barely see them, even with optics. Time passed 15 minutes, 30, an hour. The patrol didn’t move.

Complete stillness, complete silence, just waiting and watching. Then the reason became clear. NVA soldiers appeared on the trail, maybe a dozen men moving in single file, carrying supplies on shoulder poles. They were talking amongst themselves, not alert. Weapons slung casually, moving with the confidence of men who thought they owned the terrain. They passed within 20 m of where the SAS patrol was hidden.

The Australians didn’t move, didn’t engage. They’d already called in the sighting via radio. A burst transmission so quick it would be almost impossible to direction find. The intelligence was logged. The enemy counted and described. The trail marked on maps. Mission accomplished. No shots fired. No compromise.

After the NVA had passed and disappeared down the trail, the SAS patrol waited another 30 minutes before carefully withdrawing in the opposite direction, moving just as slowly and deliberately as they had arrived, leaving no sign of their presence. The SOG team watching from the Rgeline realized they just witnessed something profound.

This wasn’t reconnaissance as they’d been taught. This wasn’t about finding the enemy and calling in fire. This was something more fundamental, something older. This was hunting. To understand what changed in American thinking, you have to understand what MV SOG had been doing. And it’s crucial to say this clearly and fairly. Their methods weren’t wrong.

They were different, shaped by different missions, different strategic objectives. M. Vogg operated across the fence into Laos, into Cambodia, into areas where American ground forces officially didn’t exist and couldn’t be acknowledged. Their missions were often time-sensitive and high risk. Get in. Gather critical intelligence. Get out before the enemy reacted.

Or locate high-v valueue targets. Call in air strikes. Extract before reaction forces arrived. Or snatch a prisoner for interrogation. Fight your way to the extraction point. Get out alive. These mission parameters require different tactics. SOG recon teams move faster than SAS patrols.

They had to their time on target was measured in hours or days, not weeks. Faster than SAS patrols. They had to their time on target was measured in hours or days, not weeks. They were inserted deep into denied territory, sometimes 30 or 40 km beyond friendly lines. And the longer they stayed, the greater the chance of compromise.

They relied heavily on radio communications, checking in regularly with forward operating bases, coordinating fire support, arranging extraction. They carried more powerful radios with longer range, which meant more weight, but also more capability to call for help when things went wrong, and things went wrong frequently. SOG operations had an extraordinarily high contact rate.

These weren’t quiet reconnaissance missions where compromise meant mission failure. These were operations in areas so heavily defended that contact was almost inevitable. The enemy owned the ground. SOG teams were intruders and they had to be ready to fight. So they carried more firepower, more ammunition, 200 rounds or more per man, more grenades, claymore mines for break contact drills.

Sometimes they carried Swedish K submachine guns or sought off shotguns for close quarters fighting in thick vegetation. They needed the ability to generate overwhelming violence because that’s what saved lives when things went sideways. Their break contact drills were aggressive and effective. When a SOG team was compromised, the response was immediate and violent.

that detonate claymores, throw grenades, lay down suppressive fire, and break contact while calling in tactical air support and moving to a predetermined extraction point. The goal was to create so much chaos and destruction that the enemy couldn’t pursue effectively while the team escaped. This worked.

SOG’s record of success in impossible circumstances was remarkable. They gathered intelligence that couldn’t be obtained any other way. They disrupted enemy supply lines. They created uncertainty and fear along the Ho Chi Min Trail. They proved that small teams of highly trained soldiers could operate deep in enemy territory and survive. But it was loud, very loud.

A SOG team in contact could be heard for kilometers. The sound of claymores detonating, grenades exploding, automatic weapons fire. That noise signature announced to everyone within radio of kilometers that Americans were operating in the area. After seeing the SAS operate, some SOG operators began questioning whether loud was always necessary.

The American doctrine had been shaped by previous wars where firepower and mobility were paramount. In World War II, you advanced with armor and artillery support, suppressing enemy positions with overwhelming fire. In Korea, you held defensive lines and called in artillery strikes on any threat. Even in the early days of Vietnam, the assumption was that American technology and firepower would dominate any tactical situation.

But the jungle didn’t care about doctrine. In triple canopy forest, where visibility was measured in meters, where ambushes happened at handshake distance, where the enemy could disappear into tunnel complexes and underground facilities that were invisible from the air, firepower had limits. More importantly, SOG teams were learning that every contact, even successful ones, compromised future operations.

If you got into a firefight in a particular area, the enemy knew you were operating there. They’d increase security, change routes, set ambushes. You’d lost the element of surprise that made reconnaissance effective. The realization wasn’t that SOG was doing it wrong. It was that there might be another way to do some missions better. More silence meant more options.

If you weren’t compromised, you controlled the situation. You could observe for days instead of hours. You could gather detailed intelligence on enemy patterns. You could operate in the same area repeatedly because the enemy didn’t know to avoid it. The SAS had proven this approach worked.

But could SOG adopt it? Could they change methods that had been proven in combat, that men had died perfecting, that worked within the context of their specific missions? That was the question now being asked in team houses and forward operating bases across South Vietnam.

Not whether the SAS way was better, but whether there were circumstances where it might be more appropriate than the American way. The formal knowledge exchange happened quietly away from official channels and brass oversight. Professional soldiers talking to professional soldiers. No medal ceremony, no formal briefings, just men who respected each other comparing notes over warm beer and cigarette smoke in a team house.

After both units had returned from patrol, the Australians explained their methods patiently without any hint of superiority or condescension. They understood that the Americans weren’t asking because they’d failed. They were asking because they wanted to get better. That’s what real professionals do.

They’re always looking for ways to improve, always willing to learn, always humble enough to recognize that someone else might have a better technique. “Why the smaller teams?” one of the American Green Berets asked. “Easier to hide,” the Australian patrol commander explained, his accent thick, his manner relaxed. “Four men can move quietly. Eight men, 10 men. Someone makes noise.

Someone steps wrong. And in the jungle, one mistake compromises everyone. Smaller teams also mean you can break contact faster if things go wrong. We can disappear into terrain that wouldn’t hide a larger element. But what about firepower? What if you hit a larger enemy force? The Australian smiled.

then we’ve already made a mistake, haven’t we? Our job isn’t to fight. It’s to see without being seen. If we’re in a firefight, we’ve failed at our primary mission. Better to patrol so carefully that we never have to fight at all. Why so slow? Another American asked. We watched you for 6 hours and you covered maybe a click.

Because speed gets you killed, mate, the Australian said simply. You move fast. You miss sign. You walk into ambushes. You make noise. You compromise before you even know there’s a threat. The jungle rewards patience. Always has, always will. We learned that in Malaya, the man who rushes is the man who dies.

How do you track like that? Our guy with binoculars couldn’t see what your scout was following. years of practice. The Australian admitted, “Some bloss are naturals, grew up in the bush, learned to track RS and pigs as kids. Others learn it in training. We spend months just learning to read sign. What fresh tracks look like versus day old tracks. How vegetation recovers from disturbance.

How to read terrain and predict where someone would naturally move. It’s not magic, but it takes time to develop the eye for it. The Americans shared their expertise too. They demonstrated their break contact drills, aggressive, violent, effective. They explained how they coordinated closeair support and helicopter gunships.

They shared techniques for working with Montineyard and Vietnamese indigenous fighters, how to build trust, how to train them, how to integrate them into patrols. They discussed equipment innovations. The Americans had better radios, better communications technology. They’d developed techniques for long range insertions by helicopter that the Australians found valuable. They’d refined immediate action drills for various scenarios near ambush, far ambush, prisoner snatch, hasty ambush.

It wasn’t one-sided. Both units had genuine expertise to share. Both learned from each other. But the fundamental lesson SOG took away was philosophical rather than tactical. The Australians had internalized something the Americans were still learning. In the jungle, you are always being hunted. The enemy owns the terrain. You’re the intruder.

Your survival depends on being invisible, on moving through the environment without leaving evidence, on avoiding contact rather than seeking it. This wasn’t cowardice or timidity. This was professional fieldcraft at the absolute highest level. One SOG team leader, a captain with two tours and a chest full of decorations, later wrote in his patrol report, “The Australian SAS operates under the assumption that the enemy owns the jungle and they are merely guests moving through hostile territory. They act accordingly, quietly, respectfully,

always aware they’re in someone else’s home. This mindset, more than any specific technique, is what we need to adopt for certain mission profiles. The conversation that night went on for hours. War stories were shared. Operational philosophies were debated. Respect grew on both sides. The Americans came away with enormous admiration for what the Australians had accomplished.

These weren’t the biggest unit, didn’t have the most resources, weren’t backed by the kind of tactical air support that SAG could call on. But within their operational parameters, they were among the best jungle fighters in the world. The Australians, for their part, acknowledged that the Americans courage and aggression in impossible circumstances was something to be studied and appreciated.

SOG operators were running missions that the Australian SAS wouldn’t have been tasked with deeper penetrations, more direct action, higher risk objectives. The fact that they were surviving at all was remarkable. It wasn’t about who was better. It was about two elite units learning from each other in the hardest war of their lives. Each bringing different strengths, each willing to adapt and improve.

The moment of realization, that quiet moment when professional pride gave way to professional humility. That’s what mattered. Mac Vog realized they’d been doing reconnaissance one way. Effectively, but loudly, with methods that worked, but that had limitations. The SAS showed them there was another way. quieter, slower, more patient, optimized for different mission types, and SOG, professional to their core, decided to learn it. The transformation didn’t happen overnight.

Military institutions, even elite ones, change slowly. Doctrine that’s been written in blood isn’t abandoned casually. Men who’ve survived using certain techniques are understandably reluctant to change them. But within months of that first encounter, observable shifts started appearing in how some MAC Vogg teams conducted reconnaissance operations.

Lighter movement became emphasized in mission planning. Teams started ruthlessly stripping unnecessary weight before insertions. The question changed from might I need this to will I definitely need this. Extra ammunition was evaluated critically. Did you really need 10 magazines for a reconnaissance mission where contact should be avoided? Seations were repacked, removing excess packaging, carrying only what would actually be consumed. Unnecessary equipment was left behind.

The goal became reducing load to 50 lb or less, down from the 60 to 80 lb many teams had been humping. The difference was immediately noticeable. Lighter teams moved more quietly. fatigued less quickly, could patrol longer before needing rest. They could navigate difficult terrain more easily. They had more energy for the constant alertness that jungle operations demanded.

Silence discipline was emphasized more heavily in pre-m mission training. Teams practiced moving without talking, even during planning sessions. Hand signals were standardized across teams and drilled until they became second nature. Every man needed to understand instantly what every signal meant with no ambiguity, no confusion.

Equipment was taped, modified, adjusted to eliminate noise. Metalonmetal contact points were wrapped in cloth or foam. Cantens were filled completely so they wouldn’t slosh. Dog tags were either taped together or sewn into pockets. Anything that could rattle was secured with dummy cord or tape. Some teams started wrapping their weapons the way the Australians did. Tape around for stock and handguards to prevent wood creaking.

Slings adjusted so weapons rode secure without bouncing. Potential noise points eliminated systematically. Spacing improved on patrol. Instead of bunching up for security, a natural instinct when you’re in hostile territory, teams practiced wider dispersal. Each man maintained visual contact, but operated independently enough that a burst of fire couldn’t take multiple operators.

This required more trust, better individual skills, and constant awareness. The Australian model of diamond formation was studied and sometimes adopted. Four men spaced, so each covered a different arc, pointman watching forward and flanks, two flankers covering sides and rear security.

patrol commander positioned where he could control and communicate, each man far enough apart that they couldn’t all be caught in a single kill zone. Patrol speed decreased deliberately, at least for certain mission types. The instinct to move fast, to cover ground, to accomplish the objective quickly that had to be retrained.

Teams learned to stop more frequently, to observe, to listen. They learned that sometimes the best action was inaction, just watching and gathering intelligence without engaging. This was mentally difficult for American soldiers trained in aggressive, decisive action, but the teams that mastered it found their intelligence gathering improved dramatically.

You can’t observe patterns if you’re rushing through. You can’t gather detailed information if you’re only in position for 30 minutes. Ambush and observation approaches shifted for some operations. Rather than setting up rapid ambushes on trails, insert, set up, wait for a few hours, extract. Some teams started adopting longerterm observation posts.

They’d find good positions overlooking trails or suspected enemy areas and watch for days, gathering pattern of life intelligence before either calling in fire support or withdrawing without ever engaging. The intelligence gathered this way was more valuable. Not just enemy activity at this location, but detailed information about supply routes, movement patterns, unit compositions, and timings that could be used for larger operations. Tracking training intensified. SOG brought in expert trackers from within their own ranks,

men who’d grown up hunting, Native American soldiers with traditional tracking knowledge, anyone with genuine expertise. They ran informal classes on reading sign, on understanding how terrain influenced movement, on predicting enemy patterns. It wasn’t as comprehensive as the yearslong training pipeline the SAS used, but it was a start.

and some SOG operators proved to be natural trackers, quickly developing the eye for reading jungle sign. The results were measurable over the following months. Teams that adopted the quieter, more patient approach survived longer in denied territory. Compromise rates decreased for certain mission types. Intelligence gathered improved in both quality and detail because teams could observe longer without being detected.

Enemy units started being tracked more effectively, leading to more successful air strikes and ambushes. Most importantly for the men on the ground, casualties declined in certain types of operations. Teams that avoided contact through better stealth had fewer firefights, which meant fewer casualties, not zero.

SOG operations were inherently dangerous and contact was often unavoidable, but the trend was clear. SOG remained an aggressive kinetic force. That was their mission and they executed it brilliantly throughout the war. But now they had more tools available. They could choose to ghost through the jungle when that approach made sense.

They could choose violence when necessary. They weren’t locked into one methodology. The flexibility made them more effective overall. Different missions could be approached with different techniques. High priority targets still got the aggressive treatment, fast insertion, violent action, rapid extraction. But intelligence gathering and trail watching could now be done with the kind of patience and stealth that the Australians had demonstrated.

One Green Beret who served with SOG from 1967 to 1970 later reflected on the change. We learned that sometimes the most lethal thing you can do is nothing. Just watch, report, and let the fast movers do the killing. The Aussies taught us that patience is a weapon, maybe the most important weapon in the jungle. It took us a while to fully appreciate that, but once we did, it changed how we operated.

That lesson learned from watching four Australian SAS troopers move through the jungle like they’d been born there influenced how MV SOG operated for the rest of the war. It was a quiet transformation, never officially acknowledged, never written into doctrine in any formal way. But the men who were there remember it. They remember learning from allies who knew the jungle better than anyone else.

and they remember being professional enough to recognize excellence and humble enough to learn from it. But here’s the honest, uncomfortable truth that needs to be said clearly. Not every American unit could have done what the Australian SAS did, even with training, even with the best intentions and maximum effort. And that’s not criticism. It’s not failure.

It’s reality shaped by different circumstances, different organizational cultures, different strategic requirements. The Australian SAS was purpose-built for exactly this kind of warfare. Their entire existence, from selection through training to deployment, was optimized for small team reconnaissance in hostile jungle environments.

Everything about how they operated reflected that singular focus. selection was fundamentally different. The Australian SAS selection course was designed specifically to find men who could operate independently in harsh environments for extended periods. The course was brutal, physically demanding, yes, but more importantly, psychologically demanding in ways that tested patience, mental toughness, and comfort with isolation.

Candidates would be given minimal information and told to navigate across hundreds of kilometers of harsh terrain alone with minimal equipment. They’d be pushed to exhaustion, then given complex problems to solve. They’d be isolated, sleepdeprived, and constantly evaluated on whether they could maintain standards when everything in them wanted to quit.

The failure rate was astronomical, often 80% or higher. The men who passed were a specific type. Patient, observant, comfortable with silence and solitude, capable of maintaining discipline even when there was no external pressure forcing them to. American special forces selection, while rigorous, was testing for different attributes.

In many cases, Green Berets needed to be able to train foreign forces, speak languages, operate in teams with indigenous soldiers. Force recon marines needed to be aggressive, capable of direct action, mentally tough. SEALs needed to excel in maritime operations, demolitions, direct action raids. Different selection criteria produced different types of soldiers. Not better or worse, but different.

Cultural background mattered in ways that couldn’t be easily replicated. Many Australian SAS recruits came from rural backgrounds where self-reliance, bush skills, and tracking were normal parts of growing up. They’d learned to navigate using natural features to track animals to live in remote areas with minimal equipment.

Those skills were foundation level for them before they ever enlisted. American special forces drew from a more diverse recruitment pool. Urban soldiers, suburban soldiers, rural soldiers, all bringing different backgrounds and skill sets. Some had exceptional wilderness skills, but it wasn’t universal the way it tended to be with Australian rural recruits.

Training timelines were longer for the SAS. After passing selection, SAS troopers underwent months of specialized training before being considered fully operational. Tracking, patrolling, navigation, survival, escape, and evasion. Each skill was drilled exhaustively until it became instinctive.

An SAS trooper might spend a year or more in training before his first operational deployment. American special forces training was excellent. World class in many respects, but it generally had shorter timelines and different priorities. Green berets needed to learn languages, medical skills, communications, weapons, tactics, a broad range of skills for their advisory and unconventional warfare missions.

The training was compressed into less time because operational needs demanded it. Mission focus was narrower for the SAS. In Vietnam, they primarily conducted reconnaissance and ambush operations. That focus allowed them to refine their techniques to an extraordinary degree. Every patrol was essentially practicing the same core skills.

Repetition built mastery. M. VOG conducted reconnaissance, yes, but also direct action raids, prisoner snatches, bomb damage assessment, strategic reconnaissance, crossber operations, sabotage missions, and more. Different missions required different skill sets. SOG had to be generalists in many ways. The SAS could afford to be specialists.

Command structure and operational autonomy differed significantly. Australian SAS patrols operated with enormous autonomy. A four-man patrol might be inserted and not communicate with higher command for days. The patrol commander made realtime decisions based on his assessment of the tactical situation with minimal oversight.

American forces with superior communications technology and different doctrinal approaches maintained more frequent command contact. This had advantages, better coordination, more responsive fire support, but it also meant less operational independence. American patrols were more connected to higher command, which influenced how they operated.

National temperament and military culture played a role that’s difficult to quantify but impossible to ignore. Australian military culture inherited from British traditions and shaped by uniquely Australian experiences emphasized understatement, humility, quiet professionalism and skepticism toward authority. The ideal Australian soldier was competent without being boastful, tough without needing to prove it.

professional without being rigid. American military culture emphasized confidence, aggressive spirit, decisive action, and visible excellence. The ideal American soldier was bold, determined, took initiative, and wasn’t afraid to stand out. Neither approach is better. They’re simply different, shaped by different national histories, different founding myths, different cultural values.

These cultural differences influenced how units approached tactical problems. Australians were more comfortable with patience, with waiting, with solutions that didn’t involve direct action. Americans were more inclined toward aggressive solutions, toward doing something rather than waiting, toward decisive action that produced visible results. None of this diminishes what M. Vog accomplished.

They operated in conditions that were arguably more difficult than what the SAS faced deeper behind enemy lines with less support, facing more heavily defended targets, conducting more diverse mission types. Their courage, professionalism, and effectiveness are beyond question. But the SAS had been built from the ground up over nearly two decades for one specific type of warfare.

silent, patient, longduration reconnaissance in jungle environments. That was their specialty. Their entire organizational existence was optimized for it. American special forces were designed to fight multiple types of wars simultaneously. Conventional support operations, counterinsurgency, special reconnaissance, direct action, foreign internal defense, unconventional warfare.

They had to be adaptable, capable of switching between roles, prepared for any mission they might be tasked with. The SAS could focus on doing one or two things better than anyone else in the world. American special forces had to be competent at dozens of different mission types. That’s not a weakness of the American approach. It’s a different strategic reality reflecting America’s global commitments and the varied threats it faced.

What matters, what truly deserves respect is that MV SOG recognized excellence when they saw it. They didn’t let pride or institutional inertia prevent them from learning. They acknowledged that another unit had developed techniques that were superior for certain applications and they adapted what they could to their own operational context.

That’s the mark of true professionals, not refusing to learn because it might suggest imperfection, but actively seeking knowledge wherever it can be found from whatever source can provide it. The Australians, for their part, never crowed about their expertise. They shared it freely without seeking credit or recognition because that’s what professionals do when lives are at stake.

That mutual respect, that professional humility, that willingness to learn from allies, that’s the real story here. Decades later, the men who served remember. They remember the humidity that made every breath an effort. The weight of soaked uniforms clinging to skin. The way sweat would pour off you even when you were standing still. They remember the smell rot and cordite and fierce sweat and wet canvas. A smell you can never quite describe to someone who wasn’t there.

They remember the sounds. Rain hammering on the canopy overhead while you tried to sleep in mud that never dried. The distant thump of helicopters that might be coming to get you out or might be heading somewhere else entirely. The particular silence that fell over the jungle when something was wrong.

When the animals sensed danger and went quiet, leaving only your own heartbeat and the sound of blood rushing in your ears. They remember the weight of the gear, the way it dug into your shoulders and hips after hours of patrolling. The constant battle against leeches and mosquitoes and infections that wouldn’t heal in the humidity. The way your feet would rot if you didn’t change socks religiously.

The taste of water from streams that you knew wasn’t safe, but you drank anyway because you had no choice. But mostly they remember the men. The brotherhood that forms when you’re far from home, in danger every minute with only the men next to you standing between you and death. That bond that civilians can never quite understand. That transcends words.

That lasts a lifetime even when you haven’t seen each other in decades. In the jungle, rank mattered less than competence. The newest private who could spot signs saved everyone’s life. The veteran sergeant who knew when to move and when to freeze was worth more than gold. You trusted the man next to you? Absolutely. Completely.

Because that trust was literally the only thing between you and a body bag being loaded onto a helicopter. The Americans who served with or near the Australian SAS remember them with something close to reverence. They taught us, one former SOG operator says now, his voice quiet, his eyes distant with memory. He’s an old man now, gay-haired, living in a quiet suburb somewhere in America.

But for a moment, he’s 23 again, in the jungle, learning lessons that would keep him alive. They didn’t have to share what they knew. They could have just stayed in their lane, done their thing, left us to figure it out ourselves, but they shared. That’s what real professionals do. Another veteran asked about the Australians, shakes his head with something like wonder. Best jungle fighters I ever saw, bar none.

And I saw a lot of good men in Vietnam, American and Allied. But those sass bloss, they moved through that jungle like they owned it, like it was home. Made it look easy, which I promise you it wasn’t. The Australians, in their understated way. Remember it differently. The Yanks were good soldiers, one former SAS trooper says decades later, sitting in his home in Queensland. brave as hell.

They just needed to slow down a bit, learn to read the jungle, but they were willing to learn, which not everyone is. That counted for a lot. Another, when asked about Mac Vog, nods with genuine respect. Those blo missions we wouldn’t have been tasked with. Deeper, more dangerous, higher risk. The fact that they survived it all says something about their quality.

But underneath the understatement, there’s pride. Pride in what they accomplished. Pride in how they did it. Pride that when the Americans who had every resource, every advantage, the backing of the world’s most powerful military saw them in action, they recognized something worth learning. For men who grew up in a country often overlooked on the world stage, who served in a war their nation tried to forget, who came home to indifference, or worse, that professional respect mattered, it still matters.

Some nights, even now, they remember sitting alone in their homes, old men with gray hair, and grandchildren who ask questions they don’t quite know how to answer. They remember what it felt like to move through that jungle. The confidence that came from knowing your craft, the trust in your mates, the clarity of purpose when everything else about the war seemed confused and political and wrong.

They remember being young and fit and sharp, moving through terrain that would kill a careless man in minutes, knowing they were among the best in the world at what they did. Not bragging about it, not needing to prove it, just knowing it with quiet certainty. And on those nights, they remember with both pride and sadness. Pride in the professionalism, in the brotherhood, in the missions accomplished and the men brought home alive.

Sadness for the friends who didn’t make it back. Sadness for a war that ended badly despite everything they did. Sadness for all the things they saw that they can never quite talk about even now. But mostly they remember the work, the craft, the professionalism, the way the jungle felt.

When you got it right, when you moved through it like smoke, when you saw without being seen, when you accomplished the mission and brought everyone home alive. That’s what they carry. Not the politics, not the arguments about whether the war was justified or winnable or worth fighting, just the memory of doing impossible things with men who understood the cost.

This story isn’t really about tactics or training techniques or equipment modifications. It’s about respect. Two nations, two elite units, two completely different approaches to the same fundamental problem. how to survive and operate effectively in one of the most hostile environments on Earth. And when they met, instead of competition, there was learning.

Instead of rivalry, there was mutual appreciation. Instead of protecting expertise, there was generous sharing of hard one knowledge. The Americans could have dismissed the Australian methods. They could have said, “We’re the biggest military in the world. We have the resources. We have the technology. We don’t need to learn from a smaller ally.

They could have let pride or institutional arrogance prevent them from seeing value in a different approach. They didn’t. They watched. They learned. They adapted. What made sense for their operations. The Australians could have kept their techniques to themselves. They could have protected their competitive advantage. refused to share knowledge that had been developed over decades and paid for with Australian blood.

They could have seen the Americans as rivals rather than allies. They didn’t. They taught what they knew openly and honestly because professionals understand that sharing knowledge saves lives. That exchange, that moment of professional humility and generosity represents something larger than jungle warfare tactics. It represents what’s best about military service at its highest levels.

The willingness to say, “You know something I don’t. Teach me.” The generosity to say, “Here’s what we’ve learned. Maybe it’ll help you stay alive.” The wisdom to recognize that there are many paths to excellence. And that learning from others doesn’t diminish your own achievements. In a war that was confused and political and increasingly unpopular, where good men died for objectives that seemed to shift every month, where strategy seemed disconnected from tactical reality on the ground, this moment of professional excellence stands out. It reminds us

that even in the chaos of war, there are moments of clarity, moments when skill and experience and mutual respect create something worth remembering and honoring. The tactical lessons mattered. The improvements to how reconnaissance was conducted saved lives, improved intelligence gathering, and increased operational effectiveness for the rest of the war. But the human lesson matters more and lasts longer.

These were men who could have let pride get in the way, who could have protected institutional turf or competed for recognition or dismissed each other as different and therefore inferior. Instead, they recognized excellence and learned from it. That’s a lesson that transcends any specific tactical technique or historical period.

It’s a lesson about professionalism, about humility, about the kind of wisdom that only comes from real experience under fire. Mac V so didn’t just see a patrol that day in the jungle of Fui province. They saw a way of moving, surviving, and thinking that only Australian soldiers had truly mastered.

A way shaped by different terrain back home, different history, different culture, a way built through generations of experience in places where the bush could kill you as readily as any enemy. A way refined through years of brutal jungle warfare in Malaya and Borneo, then perfected in the green hell of Vietnam.

And decades later, the diggers who serve the ones still here, growing older, carrying memories that never quite fade, they remember one fundamental truth. In the Vietnam jungle, respect wasn’t talked about. It wasn’t given because of rank or nationality or who had the biggest guns or the most helicopters. It was earned one silent step at a time. Every patrol that came back intact.

Every mission accomplished without compromise. Every time you moved through that green hell and made it look easy, even though it never ever was. That’s what the Australian SAS did. That’s who they were. And when the best that America had to offer saw them do it, men who were themselves among the finest soldiers in the world, they stopped, watched, learned, and paid the highest compliment one professional can pay another.

They changed how they operated based on what they’d seen. That’s the story worth telling and remembering. Not about who was better. Not about national competition or rivalry. About excellence recognizing excellence. About warriors learning from warriors. About professionals sharing knowledge because lives were at stake. And that mattered more than pride.

About respect earned in the hardest classroom in the world. Where the price of failure was measured in lives. And the reward for success was simply surviving to patrol another day. The jungle remembers in its own way. The men who were there remember carrying those experiences forward through decades of life after war.

And the legacy continues in how special forces train today, in how reconnaissance is conducted, in the understanding that sometimes the most powerful weapon isn’t firepower or technology or numbers. Sometimes it’s patience, silence, the discipline to move slowly when every instinct demands action, the wisdom to watch when aggression seems like the answer.

That’s what those four Australian SAS troopers taught MV SOG on a humid day in 1966. And it’s a lesson that deserves to be remembered, honored, and passed forward to every generation of warriors that follows. Because in the end, that’s what professionalism looks like. Recognizing that there’s always something to learn. Always someone who might know a better way.

And having the humility and wisdom to learn from them. That’s the real story. That’s what matters. That’s what those men, both American and Australian, demonstrated in the jungles of Vietnam. And that’s why decades later, it still resonates with anyone who understands what it means to serve at the highest level. Claude can make mistakes.

Please double check responses.

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load