Spring 1944. The smell of wet grass and diesel fuel. That’s what Colin Barrett would remember most about that morning. Not the roar of engines or the screaming metal that came later, but the simple smell of his father’s tractor oil mixing with the damp English earth, the rolling hills outside Cambridge stretched quiet under a gray sky. Too quiet.

The kind of quiet that makes a man’s ears ring, searching for sound that isn’t there. The war had carved Britain hollow, stripped away every able-bodied man, and shipped them across the channel. What remained were boys pretending to be men, women holding together farms with blistered hands, and old men who remembered the last war and prayed this one would end differently.

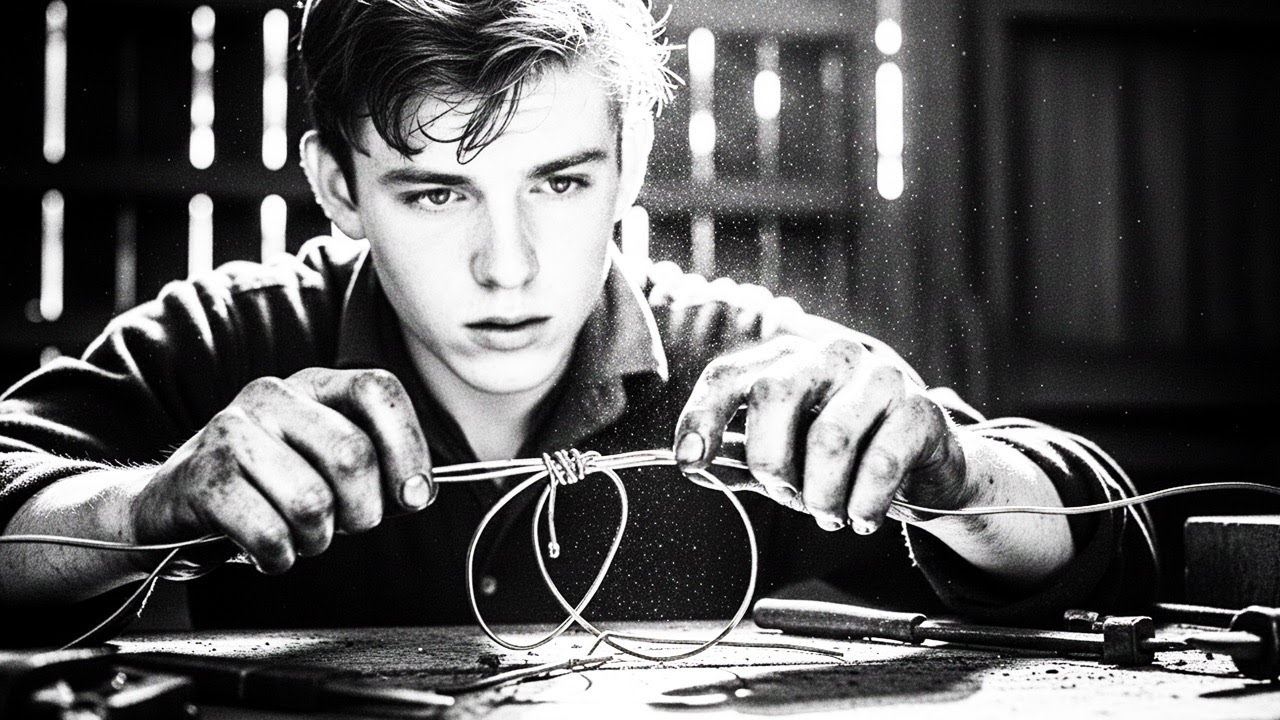

Colin was 19 years old, but his hands were 40. Calloused, stained with grease and dirt that no amount of scrubbing could remove. While other boys his age were storming beaches in Italy or flying spitfires over France, Colin stayed behind. Asthma, the doctors said, a weak chest, not fit for service, so he fixed tractors, chased chickens, and built things.

If you’re watching this and you’ve ever felt overlooked, like the world counted you out before you had a chance to prove yourself, subscribe right now and comment where you’re watching from, because this story is about to show you that sometimes the most dangerous weapon in war isn’t the one anyone sees coming.

Colin’s father thought he was wasting time. The neighbors thought he was touched in the head. Every evening after the farm work was done, Colin would disappear into the old stone barn, the one with the sagging roof and broken windows that let in the wind. He’d emerge hours later, covered in dust, eyes bright with something that looked like fever.

“What are you building in there, boy?” his father asked once, standing in the doorway with his pipe. Colin didn’t answer right away. He was winding copper wire around a wooden frame, his fingers moving with the precision of a watch maker. “Something important,” he finally said. His father grunted and walked away. “Important.” The boy had always been strange.

But here’s what Colin’s father didn’t know. What nobody in that sleepy farming village knew. Colin Barrett had taught himself radio theory from books borrowed from the Cambridge Library. He’d studied electrical engineering diagrams by candle light. He understood wavelengths and frequencies the way other boys understood cricket scores.

And for 6 months he’d been building what he called his lightning trap. It looked like madness. A maze of copper wire strung between wooden posts. Old radio parts salvaged from junkyards. Two massive water tanks filled with saltwater positioned at odd angles. Coils that sparked when the wind blew through them. The whole contraption hummed even when it wasn’t running, like it was alive, waiting. “What’s it supposed to do?” asked Mrs.

Henley from the neighboring farm, peering through the barn door one afternoon. Colin wiped his hands on his trousers. Bend radio waves. She stared at him like he’d started speaking German. Bend them? Why would anyone want to bend a radio wave? Because, Colin said quietly, his eyes fixed on something she couldn’t see.

“If you can bend them, you can hide things or make things appear that aren’t there.” Mrs. Tenley left shaking her head, muttering about boys with too much time and too little sense. But Colin kept building. April turned to May. The Apple Blossoms came and went. The BBC spoke in careful voices about advances in France, setbacks in Italy, bombing runs over German cities.

Colin listened while he worked, his hands never stopping, always twisting, soldering, connecting. He didn’t know exactly what he was making. Not really. He just knew that somewhere in the tangle of wire and salt water and electromagnetic theory, there was something important, something that could matter. His enemy wasn’t the Luftwaffer.

It was doubt, the voice in his head that whispered he was wasting his time. That he was just a farm kid with delusions. that real engineers in real laboratories were doing real work and he was playing with junk in a barn. But he kept building anyway because here’s the truth about ordinary people in extraordinary times. They don’t know they’re about to change history. They don’t wake up feeling heroic.

They just put one foot in front of the other, trusting something they can’t explain, following a thread they can barely see. Colin Barrett was about to become that person. He just didn’t know it yet. The morning of May 12th started like any other. Colin woke before dawn, fed the chickens, milked the two remaining cows, and checked the fence line on the eastern pasture.

The sky was clear for the first time in days. A brilliant, dangerous blue that stretched from horizon to horizon. At 6:47 a.m. he heard it. A low rumble from the east. At first he thought it was thunder. But thunder doesn’t stay steady. The sound grew and grew and grew. Colin shaded his eyes and looked up. They came in formation. Black crosses against blue sky. 40 of them. Maybe more.

Messmid BF19 flying low and fast. their engines screaming as they crossed over the farmland heading northwest heading for RAF Mildenh Hall. Colin stood frozen in the field, his heart hammering against his ribs. He’d seen German planes before. Everyone had They came at night, mostly heading for London or the industrial cities up north, but never like this, never in daylight, never this many, and never this low.

He could see the pilots, just dark shapes in cockpits, but he could see them. For a moment, time seemed to stop. Colin Barrett, amatic farm boy, and 40 German fighter pilots, separated by a,000 ft of air and an unbridgegable gulf of circumstance. Then something inside him snapped. What happened next would change everything.

But first, you need to understand Colin had exactly 4 minutes before those planes reached the RAF base. 4 minutes before hundreds of British pilots, mechanics, and ground crew would be caught defenseless on the runway. 4 minutes to do something impossible.

The clock was ticking, and all Colin had was a crazy contraption that even he wasn’t sure would work. Colin ran. His boots pounded across the wet grass, slipping in the mud, his weak chest already burning with the effort. The barn was 200 yd away. It felt like 2 miles. Behind him, the roar of engines faded toward the northwest. The Luftwaffer squadron was heading straight for Mildenhal, and there was nothing, absolutely nothing, that could stop them. The RAF base had been caught during a shift change.

Anti-aircraft crews were reloading. Fighter pilots were still climbing into their Spitfires. The Germans had timed it perfectly. Colin burst through the barn doors, gasping for air, his vision swimming with black spots. For a moment, he just stood there, hands on his knees, trying to remember how to breathe.

The lightning trap stood before him, exactly as he’d left it the night before. Copper coils glinted in the shaft of morning light cutting through the broken roof. The water tanks sat silent, their salt water reflecting the ceiling like dark mirrors. It had never been tested. Not really.

He’d run small experiments, created tiny electromagnetic pulses that made his father’s radio crackle, but nothing like what he was thinking now. Nothing this insane. Please, Colin whispered to no one in particular. To God, maybe to physics, to whatever force in the universe might be listening. Please let this work. He grabbed the hand crank generator, a massive thing made from an old automobile alternator and a bicycle gear system.

The crank was 4 ft long, designed to be turned by two men. Colin was alone. He started cranking. At first, nothing happened. His arms burned. Sweat poured down his face. The generator groaned and resisted. And for a horrible moment, Colin thought it had seized up, that months of sitting idle had rusted the mechanism beyond use.

Then it caught. The generator began to turn slowly at first, then faster. A low hum filled the barn. Rising in pitch, the copper coil started to glow, not with heat, but with something else. Static electricity danced between the wires like blue ghosts. Colin cranked harder, faster. His weak lungs screamed in protest.

His arms felt like they were tearing from their sockets, but he didn’t stop. The hum became a wine. The wine became a shriek. And then the air itself began to shimmer. It’s hard to explain what happened next. Even Colin couldn’t fully explain it later. The space between the copper coils seemed to bend like looking through water.

The salt water in the tanks began to bubble, not from heat, but from something else. Something that made the hair on Colin’s arm stand straight up. He could smell ozone, sharp and clean, like the air after a lightning strike. Three miles away, flight Lieutenant James Morrison sat in the cockpit of his Spitfire at RAF Mildenh Hall, listening to the frantic voice of the radar operator crackling through his headset.

Bandits inbound, 3 minutes out, altitude 500 ft, bearing 120. The radio cut to static. Morrison slapped his radio panel. Say again, tower. Say again. Nothing. just white noise. In the control tower, the radar operator stared at his screen in confusion. The German squadron had been there a moment ago, 40 clear contacts moving steadily northwest.

Now the screen showed something else, a massive reflected signal directly over the farmland south of Cambridge. It pulsed and flickered, creating an echo so strong it looked like a hundred aircraft. “What the hell?” the operator muttered. But he wasn’t the only one seeing something strange. 2,000 ft above the English countryside, Hedman Klouse Dietrich led the German formation toward their target.

He’d flown 43 combat missions. He’d bombed London, strafed convoys, and shot down six RAF fighters. He was professional, calm, experienced, which is why he noticed immediately when his instruments went mad. The compass spun wildly, needle whirling like a mad thing, the radio filled with high-pitched squealing that made his ears ring. The magnetic heading indicator flickered and died.

And strangest of all, the air ahead seemed to shimmer, creating a visual distortion that looked almost like heat waves rising from pavement. Klene, are you seeing this? Dietrich radioed to his wingman. No response, just that horrible squealing. Dietrich looked left.

Klein’s messes was still there keeping formation, but the pilot was clearly wrestling with his controls, his head moving frantically between instruments. Then came the collision. Nobody saw it coming. One moment the formation was intact. The next, two planes on the left flank drifted into each other, their wing tips catching. Metal shrieked. One plane spun away, trailing smoke.

The other went into an uncontrolled dive. “Break formation!” Dietrich shouted into dead air. “Break! Break!” But his order never transmitted. The electromagnetic pulse from Collins’s lightning trap had created a bubble of chaos over the English countryside, and 40 German pilots had just flown straight into it. Back in the barn, Colin collapsed.

His arms gave out. He fell to his knees, gasping. the generator handle spinning free. But it didn’t matter. The device had achieved critical resonance. It was running on its own now, drawing power from some interaction between the electromagnetic field and the Earth’s natural magnetic forces that Colin didn’t understand and couldn’t control.

The coils glowed brighter. The air crackled with energy. And three miles away, 40 of Germany’s finest pilots fought desperately against forces they couldn’t see or understand. Messes broke formation in every direction. Some dove for the deck, thinking they’d been hit by anti-aircraft fire.

Others climbed, trying to escape the invisible field that scrambled their instruments. Three more planes collided. One spun into a marsh with a geyser of muddy water. Another clipped a treeine and cartwheeled across a field, scattering sheep in every direction. The RAF pilots at Mildenhal scrambled into the air, expecting a fight. What they found instead was carnage.

German fighters scattered across the sky like confused birds. Some fleeing east, others circling aimlessly, all of them completely disoriented. Flight Lieutenant Morrison couldn’t believe what he was seeing. Tower, confirm. Are we under attack? The radar operator’s voice came back equally confused. Negative. The bandits are They’re retreating. They’re all over the map.

I don’t understand what’s happening. Nobody did, except maybe one gasping, trembling farm boy kneeling on a barn floor, watching his impossible machine tear itself apart. Because here’s what nobody knew yet. What wouldn’t be discovered for days. Colin Barrett’s lightning trap hadn’t just jammed radio signals.

It had accidentally recreated a phenomenon that Britain’s top scientists were still struggling to understand. a phenomenon that would later be called radar spoofing. And it was about to get much, much stranger. Colin didn’t see the sky that morning. He was lying on the barn floor, his chest heaving, staring up at the rafters while blue lightning danced above his head. The copper coils were melting.

He could smell it. hot metal and burning insulation mixing with the ozone until the air itself seemed poisonous. He tried to stand. His legs wouldn’t work. His arms felt like dead weight. For a terrifying moment, he thought he was dying, that his weak heart had finally given out, that this stupid, desperate gamble had killed him. Then the humming stopped.

The silence hit like a physical thing. One moment the barn was screaming with electromagnetic fury. The next, nothing. Just the drip of water from the leaking roof and the distant sound of aircraft engines fading toward the horizon. Colin rolled onto his side and vomited into the dirt. When he finally managed to stand, his legs shaking beneath him.

He stumbled to the barn door and looked out at the sky. It was empty, clear blue, stretching forever, innocent as Sunday morning, like nothing had happened, like the world hadn’t just tilted on its axis. But something had happened. Colin could feel it in his bones.

3 mi northwest, RAF Milden Hall looked like someone had kicked over an antill. Pilots ran across the tarmac. Ground crews shouted orders. Spitfires taxied in every direction, their propellers whirling, ready for a fight that had already ended. Flight Lieutenant Morrison brought his fighter down hard, his mind still reeling from what he’d witnessed. 40 German aircraft, 40 scattered like leaves in a storm.

Some had fled east. Some had crashed. Some had simply vanished into the clouds, their pilots too disoriented to press the attack. In 5 years of war, Morrison had never seen anything like it. “What happened up there?” the ground crew chief asked as Morrison climbed out of his cockpit.

Morrison pulled off his flight cap and ran a hand through his sweat soaked hair. “I don’t know, Chief. I honestly don’t know, but someone was beginning to understand. In the radar room, the operator sat staring at his screen, his hand hovering over the telephone that connected him to Fighter Command headquarters in London. He’d been trained to report anomalies.

This was more than an anomaly. This was impossible. The radar trace had shown a phantom target, a massive reflected signal that appeared over empty farmland and somehow drew 40 enemy aircraft toward it like moths to flame. The signal had pulsed for exactly 4 minutes, then vanished as completely as it had appeared.

The operator had two choices. He could report what he’d seen and sound like a mad man or he could say nothing and possibly miss something critical. He picked up the phone. “Get me Dr. Harold Gley,” he said. “Tell him it’s urgent. Tell him we’ve got something he needs to see.” 4 days passed before they came for Colin.

4 days of confusion and wild rumor. Four days of villagers whispering about the German planes that fell from the sky. Four days of Colin lying awake at night, staring at his ceiling, wondering if he’d imagined the whole thing. He’d gone back to the barn the day after. The lightning trap was destroyed. The copper coils had melted into twisted lumps of metal.

The wooden frames were charred black. The water tanks had cracked from thermal stress. Their salt water spilled across the dirt floor in dark stains that looked almost like blood. Colin had built something, and then that something had burned itself out of existence, leaving behind only ash and questions.

He was mucking out the chicken coupe when the car arrived. A black Austin, official looking, with two men in civilian clothes who moved like soldiers. Colin’s father came out of the house, wiping his hands on his apron, his face creased with concern. Colin Barrett? The taller man asked. Colin’s throat went dry. Yes, sir. I’m Dr.

Harold Gley, Ministry of Supply. This is Captain Winters, RAF Intelligence. We’d like to ask you some questions about what happened here on May 12th. Colin’s father stepped forward. What’s this about? My boy hasn’t done anything wrong. Dr. Gley smiled, but it didn’t reach his eyes. No one’s suggesting he has, Mr. Barrett. Quite the opposite, in fact.

They went to the barn, all four of them. Colin’s father insisted on coming, his protective instincts overriding his usual deference to authority. Captain Winters carried a briefcase. Dr. Gley carried a notebook and three different kinds of measuring equipment. When they stepped inside and saw the melted remains of the lightning trap, Dr. Gley went very still.

“Good God,” he whispered. He moved closer, crouching beside the ruined coils, his fingers hovering over the metal without quite touching it. Captain Winters took photographs. Flash bulbs popped in the dim barn, freezing moments in stark black and white. Colin, Dr. Gley said quietly, not looking up.

Tell me exactly what you built here. So Colin told them about the copper wire and the radio parts, about the saltwater tanks and the hand crank generator, about electromagnetic theory and wavelength manipulation and ideas he’d pulled from library books and his own fevered imagination.

He told them about the morning of May 12th, about cranking the generator until his arms burned, about the blue lightning and the shimmer in the air and the smell of ozone. so strong it made his eyes water. And when he was done, Dr. Gley stood up slowly, like a man coming out of a dream, and said the words that would haunt Colin for the rest of his life.

You shouldn’t have been able to do this. Silence filled the barn. “What do you mean?” Colin’s father asked. Dr. Gley turned to face them, and for the first time, Colin saw something in his eyes that looked like fear. We’ve been working on radar countermeasures for 18 months.

The best scientists in Britain, proper laboratories, unlimited resources. We’re still years away from creating what your son built in a barn with salvaged junk. Captain Winters closed his briefcase with a sharp snap. The question is, how did he do it? I don’t know, Colin said honestly. I just I had an idea. and I followed it. Dr. Gley shook his head slowly. Ideas don’t create electromagnetic pulses strong enough to scramble instruments 3 mi away.

Ideas don’t generate false radar signals. What you did here shouldn’t be possible with this equipment. It shouldn’t even be theoretically possible. He pulled a small device from his pocket, a geer counter, Colin realized with a chill and waved it over the ruined coils. It clicked steadily, not dangerously high, but present, measurable.

You created a sustained electromagnetic field with enough power to affect aircraft electronics at range. You generated a radar reflective plasma signature using nothing but salt water and copper wire. and you did it without killing yourself in the process. Dr.

Gley looked at Colin with something that might have been awe or might have been horror. Do you understand what I’m telling you? Colin shook his head. You’ve accidentally invented something that could change modern warfare. Something we don’t fully understand. Something that maybe can’t be replicated. The words hung in the air like smoke. What happens now? Collins father asked, his voice rough with fear and pride in equal measure. Captain Winters answered, “Now, Mr.

Barrett, this barn is classified. Everything that happened here is classified. Your son is classified.” But here’s the twist that nobody saw coming. The twist that wouldn’t surface until 50 years later when the files were finally declassified and historians could piece together the full story.

Colin Barrett’s lightning trap hadn’t just jammed radio signals and created false radar echoes. It had done something else. Something the scientists in 1944 couldn’t explain. It had worked because it shouldn’t have worked. And that impossibility would haunt British military intelligence for decades. They took everything. Not by force. The British don’t do things that way. But over the next 3 weeks, men in civilian clothes came and went from the Barrett farm, carefully photographing, measuring, and cataloging every piece of the lightning trap. They dug up the earth where the salt water had spilled, looking for chemical residue. They

interviewed Colin for hours, asking the same questions in different ways, as if repetition might unlock some secret he was keeping. But there was no secret, just a farm boy who’d read too many books and trusted an instinct he couldn’t explain. By June, the barn was empty.

The equipment was gone, transported to some government facility where proper scientists could study it in proper laboratories. Colin received an official letter thanking him for his contribution to the war effort and reminding him that everything related to May 12th was covered by the Official Secrets Act. He never spoke about it publicly, not once, not even after the war ended.

Life returned to normal or something like it. Colin fixed tractors, chased chickens, and watched the sky. Always watching the sky. His father never asked about that day again, sensing that some doors once closed should stay closed. The Luftwaffer never returned to Cambridge. But here’s what Colin didn’t know.

What he couldn’t know. Sitting on his quiet farm while the war raged on across Europe. In a basement laboratory beneath London, Dr. Harold Gley worked 16-hour days trying to understand what had happened in that barn. He had the equipment. He had Collins detailed descriptions.

He had measurements, photographs, and eyewitness accounts from the RAF pilots who’d seen the German formation scatter like frightened birds. But he couldn’t replicate it. Every attempt failed. Oh, they could generate electromagnetic pulses. They could create radio interference. But that sustained field, that phantom radar echo strong enough to confuse 40 pilots simultaneously, that remained stubbornly out of reach.

“It’s like he stumbled onto something by accident,” Gley told his assistant one night, exhausted and frustrated. “Some combination of factors we can’t identify. the weather that morning, the mineral content in his water, the frequency he happened to generate something. His assistant looked at the pile of failed experiments on the workbench. Or maybe he’s just special.

Maybe some people can do things the rest of us can’t. Gley didn’t believe in magic. He believed in science. But late at night, when the equations refused to balance and the experiments refused to work, he wondered if maybe the universe had room for both. The war ended, Europe celebrated, soldiers came home, and the world tried to forget 5 years of horror and destruction. Colin Barrett never built another machine.

People asked him why, his father asked. Dr. Gley asked in letters that came occasionally from London, polite inquiries wrapped in official language, but Colin never gave a straight answer. The truth was simpler and stranger than anyone imagined. Colin was afraid, not of the government, or the official secrets act or getting in trouble. He was afraid of the power he touched that morning in the barn.

The moment when copper and salt water and desperate prayer had combined into something that bent the laws of physics, something that felt alive. He’d looked into that blue lightning and seen something looking back. Years passed, decades. The lightning trap became a legend in Cambridge, whispered about in pubs by old men who’d been young during the war.

Most people thought it was exaggeration, a myth, one of those stories that grows in the telling until the truth is buried under layers of imagination. But the veterans who’d been at Milden Hall that morning, they knew better. They’d seen the German formation scatter. They’d watched planes collide midair for no reason. They’d felt the static electricity crackling through their radio headsets.

They knew something impossible had happened. They just didn’t know how to explain it. In 1994, 50 years after that spring morning, the British government began declassifying wartime documents. Historians dug through boxes of yellowed paper, piecing together stories that had been hidden for half a century.

And that’s when someone found the file on Colin Barrett, the researcher who discovered it. A young woman named Dr. Sarah Mitchell, almost missed it. The file was thin, marked with multiple classification stamps, buried in a box labeled experimental defense systems, 1944, 1945. She opened it, expecting routine weapon tests.

What she found instead made her sit down hard in her chair and read the entire file three times before she believed it. Colin Barrett’s lightning trap hadn’t been random. It hadn’t been luck or divine intervention or accident. According to the scientist’s notes, notes that had remained classified for five decades, Colin had independently discovered the principles of radar jamming and electronic warfare that wouldn’t be officially developed until the 1960s.

He’d been 20 years ahead of his time. And he’d done it in a barn with salvaged junk. But here’s the final twist. The twist that makes this story more than just an interesting footnote in military history. Dr. Mitchell kept digging. She found weather reports from May 12th, 1944. She found geological surveys of the Cambridge area. She found chemical analyses of the water from Collins farm.

And she found something that made every scientist who looked at it go very quiet. The soil around Colin’s barn had unusually high concentrations of magnetite, a naturally magnetic iron oxide. The water from his well had elevated levels of dissolved minerals that could theoretically enhance electrical conductivity.

And on the morning of May 12th, Cambridge had experienced unusual atmospheric conditions that created a natural ionospheric disturbance. In other words, Colin Barrett had built his lightning trap in the one place at the one time where the Earth itself was primed to amplify electromagnetic energy. He’d been brilliant, but he’d also been impossibly lucky. Dr. Mitchell published her findings in 1997. The story made headlines for about a week.

Some called Colin a forgotten hero. Others called it exaggerated wartime mythology. But here’s what matters. What really matters beyond the science and the history and the debate. Colin Barrett died in 1989, 5 years before the files were declassified. He died quietly in his sleep on the farm where he’d spent his entire life. He never knew that historians would eventually vindicate him.

He never knew that his crazy trick would be studied in militarymies and electrical engineering courses. He died thinking he’d gotten lucky once a long time ago on a morning when the sky was full of danger and he’d been desperate enough to try something impossible. Colin Barrett saved hundreds of lives that morning.

British pilots, ground crews, people who went home to their families because 40 German fighters never reached their target. History remembers the generals and the fighter races, the big battles with the big names. But it was the engineer in the barn, the farm boy with crazy ideas, who changed the outcome of one very important morning in the spring of 1944.

His story reminds us that courage doesn’t always wear a uniform. Sometimes it wears overalls and smells like diesel fuel and doesn’t even realize it’s being brave. So here’s my question for you. If you were Colin standing in that field watching those planes approach, would you have run toward the barn or away from it? Drop your answer in the comments and tell me where you’re watching from around the world.

I read every single comment and your stories matter. If this forgotten piece of history moved you, if it reminded you that ordinary people can do extraordinary things, then do me a favor. Hit that subscribe button and join the Echoes of London family. We tell stories like this every day. stories that deserve to be remembered. Stories about courage that history almost forgot.

Thank you for watching. Thank you for caring about these stories. And remember, the next time you think you’re too ordinary to make a difference, think about Colin Barrett and his lightning trap. Sometimes the most powerful weapon in the world is one person who refuses to do nothing. I’ll see you in the next story.

News

The Kingdom at a Crossroads: Travis Kelce’s Emotional Exit Sparks Retirement Fears After Mahomes Injury Disaster DT

The atmosphere inside the Kansas City Chiefs’ locker room on the evening of December 14th wasn’t just quiet; it was…

Love Against All Odds: How Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Are Prioritizing Their Relationship After a Record-Breaking and Exhausting Year DT

In the whirlwind world of global superstardom and professional athletics, few stories have captivated the public imagination quite like the…

Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Swap the Spotlight for the Shop: Inside Their Surprising New Joint Business Venture in Kansas City DT

In the world of celebrity power couples, we often expect to see them on red carpets, at high-end restaurants, or…

The Fall of a Star: How Jerry Jeudy’s “Insane” Struggles and Alleged Lack of Effort are Jeopardizing Shedeur Sanders’ Future in Cleveland DT

The city of Cleveland is no stranger to football heartbreak, but the current drama unfolding at the Browns’ facility feels…

A Season of High Stakes and Healing: The Kelce Brothers Unite for a Holiday Spectacular Amidst Chiefs’ Heartbreak and Taylor Swift’s “Unfiltered” New Chapter DT

In the high-octane world of the NFL, the line between triumph and tragedy is razor-thin, a reality the Kansas City…

The Showgirl’s Secrets: Is Taylor Swift’s “Perfect” Romance with Travis Kelce a Shield for Unresolved Heartbreak? DT

In the glittering world of pop culture, few stories have captivated the public imagination quite like the romance between Taylor…

End of content

No more pages to load