In the world of sports, few things ignite more passion, fury, and endless debate than a “greatest of all time” list. It is a declaration, a line in the sand that attempts to chisel legacy into stone. This week, the Associated Press, in honor of the 50th anniversary of its women’s basketball poll, did just that. They assembled a panel of 13 former players and AP sports writers to name the all-time greatest players in women’s college basketball history. And in doing so, they lit a match and tossed it into a storehouse of cultural and athletic dynamite.

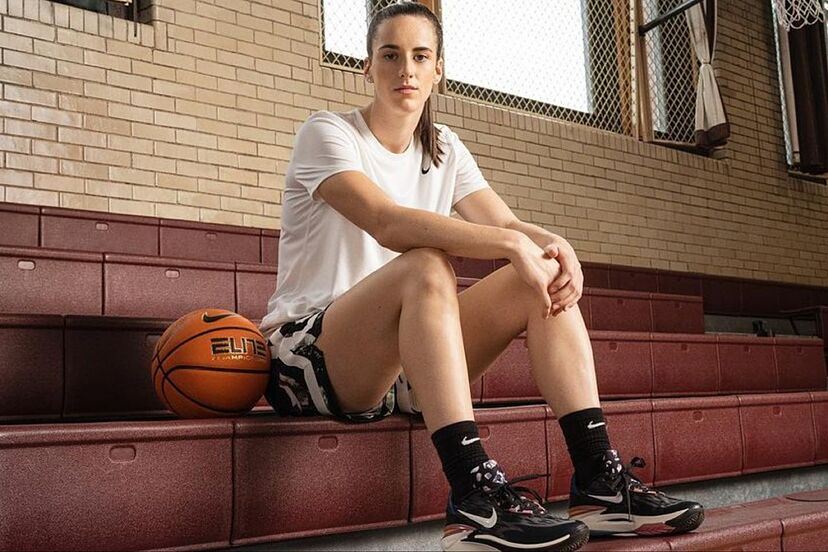

The resulting first team is a pantheon of titans: Brianna Stewart, Candace Parker, Cheryl Miller, and Diana Taurasi. And then, there is the fifth name: Caitlin Clark.

The moment the list was published, the internet fractured. The inclusion of the Iowa sensation—arguably the most transformative college athlete of her generation—was met with both rapturous applause and absolute, unadulterated outrage. The reason is simple, stark, and to many, disqualifying: Every other member of that first team is an NCAA champion. Caitlin Clark is not.

This single fact has triggered a meltdown of spectacular proportions, dominating sports talk, flooding social media timelines, and exposing a deep, fundamental rift in how fans, media, and even players define “greatness.” The backlash has been swift and merciless, with thousands crying foul that a player who never won the ultimate prize could be elevated above legends who did.

The central argument of the critics is laser-focused on championships. How, they ask, can Clark be on the first team when a icon like Maya Moore—a two-time national player of the year and two-time NCAA champion—was relegated to the second team? Social media comments have been brutal: “All these players won national championships except one.” “Where are the chips?” “This is a joke, it’s all about hype.” “Ain’t no way in hell she’s better than Maya Moore in college.”

To her critics, this is an unforgivable sin, a recency bias that disrespects the very foundation of competitive sport: winning. They see it as a publicity stunt, a nod to her current fame rather than a sober reflection of her place in history. They argue that to be the “greatest,” one must complete the journey. For them, the debate is over before it begins. No ring, no entry.

But this fiery, single-minded argument misses the entire point. It conveniently, and perhaps deliberately, ignores the very rules of engagement set forth by the AP panel itself.

The 13 voters, which included legends like Rebecca Lobo, were not instructed to simply count rings. The official criteria given to the panel were explicit. They were to select players based on their college careers only, considering “championship pedigree, record-breaking statistics or simply their ability to will their teams to victory.”

The operative word here is or.

The outrage mob has clung to the first criterion as if it were the only one. They have forgotten, or chosen to forget, the other two. And it is in those other two categories that Caitlin Clark does not just qualify; she may well be the new standard.

Let’s talk about “record-breaking statistics.” Clark’s college career was a four-year statistical supernova. She didn’t just break the all-time NCAA Division I scoring record; she shattered it, obliterating a 54-year-old benchmark held by “Pistol” Pete Maravich. She became the only D-I player in history—man or woman—to amass over 3,000 points and 1,000 assists. She is a three-time AP Player of the Year. Her statistical dominance is not just impressive; it is unprecedented. On this criterion alone, her case for the first team is ironclad.

Then, let’s look at the third criterion: “ability to will their teams to victory.” This is perhaps her most potent qualifier. Did she win a title? No. But she took an Iowa program that was not a traditional blue-blood powerhouse and willed them to back-to-back national championship game appearances. She put an entire university, state, and at times, the entire sport on her back and carried it to heights it had never seen.

But her “ability to will” went beyond the box score. It extended past the court and into the very fabric of American culture. This is the “Caitlin Clark Effect.” She willed millions of people to watch women’s basketball for the first time. Her games smashed viewership records, with her final collegiate game drawing more viewers than the Men’s NCAA final for the first time in history. She willed networks to change their programming, willed ticket prices to skyrocket, and willed the national conversation to center on her sport.

The very people who are so furiously debating this list are, in many ways, only doing so with this level of passion because of Caitlin Clark. She is the conversation. That, in itself, is a form of greatness the AP panel rightfully recognized.

The “haters,” as they’ve been dubbed by defenders, are not just arguing against Clark; they are arguing against a new definition of legacy. They are stuck in a rigid, outdated mindset that a player’s worth can be boiled down to a binary “champion or not.” It’s a comfortable, easy metric that requires no nuance. It’s the argument of someone who wants a simple answer to a complex question.

This debate is not really about Caitlin Clark versus Maya Moore. It’s about a philosophical war: Is greatness defined only by its conclusion, or is it defined by the journey and the sheer, earth-moving force of the talent itself? Is it better to be a critical cog in a dynastic championship machine, or is it better to be a singular force of nature who revolutionizes the game, captures the world’s attention, and rewrites the record books, falling just short of the final prize?

The AP panel, with its multi-faceted criteria, made a modern, intelligent choice. It declared that greatness is not a monolith. It recognized that a player who scores more points than anyone in history and single-handedly elevates their sport to a new stratosphere of cultural relevance has a resume that is just as powerful, just as “great,” as one who holds a trophy.

Caitlin Clark’s inclusion on the all-time first team is not an insult to the legends who came before her. It is an acknowledgment that the game has evolved, and the ways in which a player can achieve immortality have evolved with it. She didn’t just play the game; she changed it. And that, by any definition, is the very essence of all-time greatness.

News

Little Emma Called Herself Ugly After Chemo — Taylor Swift’s Warrior Princess Moment Went VIRAL BB

When Travis Kelce’s routine visit to Children’s Mercy Hospital in November 2025 led him to meet 7-year-old leukemia patient Emma,…

The Coronation and the Cut: How Caitlin Clark Seized the Team USA Throne While Angel Reese Watched from the Bench BB

The narrative of women’s basketball has long been defined by its rivalries, but the latest chapter written at USA Basketball’s…

“Coach Made the Decision”: The Brutal Team USA Roster Cuts That Ended a Dynasty and Handed the Keys to Caitlin Clark BB

In the world of professional sports, the transition from one era to the next is rarely smooth. It is often…

Checkmate on the Court: How Caitlin Clark’s “Nike Ad” Comeback Silenced Kelsey Plum and Redefined WNBA Power Dynamics BB

In the high-stakes world of professional sports, rivalries are the fuel that keeps the engine running. But rarely do we…

The “Takeover” in Durham: How Caitlin Clark’s Return Forced Team USA to Rewrite the Playbook BB

The questions surrounding Caitlin Clark entering the Team USA training camp in Durham, North Carolina, were valid. Legitimate, even. After…

From “Carried Off” to “Unrivaled”: Kelsey Mitchell’s Shocking Update Stuns WNBA Fans Amid Lockout Fears BB

The image was stark, unsettling, and unforgettable. As the final buzzer sounded on the Indiana Fever’s 2025 season, Kelsey Mitchell—the…

End of content

No more pages to load