At 11:47 on the morning of February 9th, 1945, Private First Class Cleto Rodriguez crouched 18 m from the main entrance of Paco Railroad Station in Manila. In his hands, a type 99 Japanese light machine gun, 10.4 kg, 7.7 mm caliber, 750 rounds per minute. the weapon that had killed three of his platoon mates 90 minutes earlier.

Rodriguez was 21 years old, Mexicanamean, San Marcos, Texas. Before the war, he delivered newspapers at the Gunter Hotel in San Antonio. No military lineage, no formal weapons training before enlistment. 12 months earlier, he had not known how to field strip a bar. Now he was holding a captured enemy machine gun 30 seconds before throwing five M2 grenades through a doorway that would kill seven Japanese soldiers and wreck a 20 mm cannon.

His company commander had called the advance suicide. His sergeant had told him to fall back. Rodriguez did not fall back. He moved forward. Over the next 2 and 1/2 hours, he would kill 82 enemy soldiers. This is how a news boy from Texas used the enemy’s own weapons to save Paco Station and learned that when your rifle runs dry, you don’t retreat.

You find another rifle. February 9th, 1945,0900 hours. Manila, 3 days after American forces began the assault to retake the city. Company B, First Battalion, one 48th Infantry Regiment, 37th Infantry Division, had received orders to capture Paco Railroad Station. The station was concrete reinforced pre-war construction from the 1930s.

100 to 150 m in length, two to three stories, thick walls with sandbag firing positions. Intelligence estimated 50 to 80 Japanese soldiers inside. Defensive imp placements included type 99 light machine guns, a 20 mm cannon, heavy machine guns, multiple pill boxes surrounding the perimeter. The Japanese had transformed a civilian transportation hub into a fortress.

Rodriguez carried his primary weapon, the Browning automatic rifle M1918 A2, 8.8 kg unloaded, 9.3 with a 20 round magazine of 306 Springfield ammunition. Rate of fire, 550 rounds per minute on the fast setting. Effective range 457 m. Rodriguez carried four extra magazines on his belt, 80 rounds total. At sustained fire, that gave him approximately 4 minutes of shooting before running dry.

His partner was private first class John N. Reese Jr. from Prior, Oklahoma. Ree carried an M1 Garand 8.7 lb semi-automatic 8 round NB block clips. Reese’s job was covering fire while Rodriguez maneuvered. The platoon advanced across open ground toward the station. 100 yards of flat terrain with minimal cover. Japanese fire opened at 0900.

Concentrated machine gun bursts from multiple positions. The sound was distinctive. The type 99’s higher pitched crack versus the bar’s heavier report. Three men dropped in the first 15 seconds. The platoon went to ground. 40 men pinned down by interlocking fields of fire from a fortress they could not approach without taking catastrophic casualties.

Rodriguez looked at Ree. No words. Ree nodded. They left the platoon and ran forward. They sprinted 60 yards to a bombed out residential structure, one to two stories, partially collapsed walls, windows facing the station. The distance to Paco station was now 60 yards, approximately 55 m. Japanese fire intensified as they moved, bullets snapping past, impacting concrete around them, kicking up dust.

They reached the house at 09:15. Rodriguez took the north window, Ree, the east. They began engaging targets of opportunity for 1 hour from 0915 to 10:15. Rodriguez and Ree fired from that house. Rodriguez used the BAR in controlled bursts, 3 to five rounds per trigger pull to conserve ammunition. Ree fired semi-automatic with the Garand, one shot per squeeze.

The technique was alternating fire. When Rodriguez reloaded, Reese shot. When Ree reloaded, Rodriguez covered. The Japanese identified their position within 10 minutes and began concentrating suppressive fire on the house. rounds shattered remaining glass, chewed through wooden window frames, punched holes in plaster walls.

Rodriguez and Ree kept shooting. By 0930, they had killed eight Japanese soldiers attempting to man the pillbox positions outside the station. By 0950, the count was 20. The Japanese changed tactics. Instead of exposing themselves, they fired blind from behind cover, spraying rounds toward the house without aiming. Rodriguez adjusted.

He watched for muzzle flash, waited for soldiers to shift positions, took the shot when they moved. At 10:03, Rodriguez fired his last bar magazine, 20 rounds. Ree called out, “I’m down to two magazines.” 16 rounds remaining. Rodriguez scanned the area between the house and the station. Movement.

40 to 50 Japanese soldiers, replacements, attempting to reach the pill boxes to reinforce the defensive positions. If they reached the pill boxes, the American advance would stall indefinitely. Rodriguez pointed. Ree saw them. They left the house at 10:15 and ran toward the enemy reinforcements. They covered 40 yards using rubble and destroyed vehicles for concealment.

Reached a collapsed concrete wall with a clear line of sight to the approaching Japanese column, now 80 yards distant. Rodriguez set up the bar on the walls edge. Ree positioned 3 m to his left with the Garand. They opened fire at 10:45. The Japanese were moving in a loose formation, not expecting contact from that angle.

Rodriguez fired in sustained bursts, sweeping left to right across the formation. The bar’s 550 rounds per minute chewed through the column. Ree picked off soldiers attempting to take cover. For 30 minutes, Rodriguez and Ree massacred the reinforcement group. The Japanese tried to retreat back toward the treeine, but were caught in open ground.

Some attempted to rush forward to the pill boxes, but were cut down before reaching cover. By 11:10, 40 Japanese soldiers lay dead in the field. Rodriguez chambered his last round. The bar was empty. Ree fired his final four rounds and called out, “I’m dry.” Total kills in two hours, 75 plus. Total ammunition expended 160 rounds from Rodriguez’s bar, approximately 112 rounds from Reese’s Garand.

The platoon remained pinned 100 yd behind them. No resupply possible. Paco station still occupied 20 yards ahead. Rodriguez looked at the station entrance, saw a body, Japanese soldier dead from the earlier firefight. Next to the body, a type 99 light machine gun. Rodriguez crawled 10 m to the body while Ree provided security.

The Type 99 lay on its side, bolt open. Rodriguez picked it up. 10.4 kg, 1.6 kg heavier than the BAR. He checked the magazine. 18 rounds of 7.7 mm Arisaka ammunition remaining. found three additional 30 round magazines on the dead soldier’s belt. Total available 108 rounds. Rodriguez had trained with captured Japanese weapons during the month of combat in Luzon before Manila.

He knew the Type 99, knew the safety mechanism, the magazine release, the sight adjustments. The weapon was similar in operation to the BAR, but with a higher rate of fire, 750 rounds per minute, and a detachable magazine that reloaded faster than the BAR’s bottom-mounted fixed magazine. At 1120, Rodriguez test fired the Type 99.

Eight round burst toward a pillbox firing slit. The sound was different from the BAR, a sharper crack from the 7.7 mm cartridge. The recoil impulse was snappier. Japanese soldiers in the station hesitated for 2 seconds when they heard the Type 99’s report. They heard their own weapon. Confusion bought time. Rodriguez used that time.

He advanced in 5 m bounds while Ree fired the last four rounds in his Garand to suppress the station’s firing ports. Ree was now completely out of ammunition, but kept presenting the rifle to create the impression of active threat. Rodriguez reached 30 yards from the station at 11:30, killed three Japanese soldiers at the side entrance, pushed forward to 20 yards at 11:40.

Heavy machine gun fire from inside forced him behind a pile of rubble. At 11:45, Rodriguez reached the exterior wall 18 m from the main entrance. He had the Type 99 with 12 rounds remaining and five MK2 fragmentation grenades on his belt. He could not see inside the doorway, but heard voices, movement, the metallic sounds of weapons being reloaded.

Rodriguez pulled the pin on the first grenade, counted two seconds, threw it through the doorway. The explosion destroyed the 20 mm cannon position. Grenades 2 through 5 followed in rapid sequence. 5 seconds of overlapping detonations. When the smoke cleared, seven Japanese soldiers were dead inside the entrance.

The heavy machine gun was wrecked and the main defensive position was neutralized. At 11:52, Rodriguez called to Ree, “We’re out. Fall back.” They began the tactical withdrawal, alternating covering fire. Rodriguez moved first, running 10 m, while Ree aimed the empty Garand at the station to simulate suppression.

Then Ree ran while Rodriguez fired three to four round bursts from the Type 99. At 12:02 they had gained 40 yards. Japanese fire increased. Soldiers inside the station realized the Americans were retreating and tried to capitalize. At 1211, Ree was running 10 m from Rodriguez. A Japanese round hit center mass. Ree dropped.

Rodriguez went back, dragged Ree to cover behind a destroyed wall. Ree was bleeding heavily, sucking chest wound. He looked at Rodriguez and said, “Go. I’m done.” Rodriguez said nothing. He stayed for 30 seconds applying pressure, knowing it was insufficient. Then he ran, reached American lines at 12:15 alone. 82 Japanese soldiers confirmed dead in 2 and 1/2 hours. John Ree died at 12:20.

Rodriguez was promoted to technical sergeant in the field. 2 days later, on February 11th, Rodriguez conducted another solo action, killed six more enemy soldiers, destroyed another 20 mm gun. On February 23rd, 1945, President Harry Truman presented Rodriguez with the Medal of Honor. The citation read, “Conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action above and beyond the call of duty.

” Rodriguez’s action at Paco Station saved an estimated 50 to 100 American lives by eliminating the fortified position without requiring a fullscale assault. The 37th Division suffered 45 killed and 307 wounded during the battle for Manila. Rodriguez’s improvisation using captured enemy weapons when American ammunition ran out was not adopted as formal doctrine.

The US Army never trained soldiers to routinely employ enemy firearms. But Rodriguez proved a principle that every soldier who survives long enough learns. When your weapon is empty, you don’t need to retreat. You need to find another weapon. Cle Rodriguez survived the war, discharged in 1945, reinlisted in the Air Force from 1952 to 54, returned to civilian life in San Antonio, Texas.

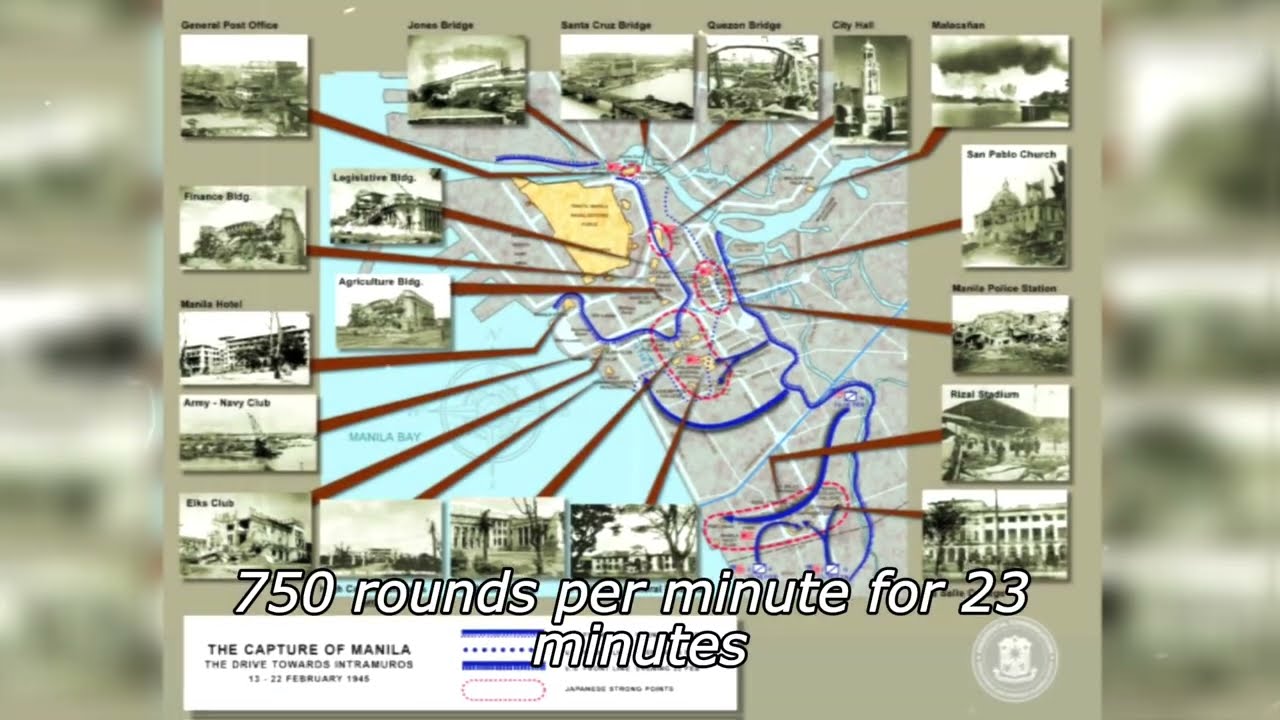

He rarely spoke about Manila. On December 7th, 1990, Rodriguez died at age 67. He is buried in San Antonio. The type 99 machine gun he captured and used during the withdrawal was never recovered. Discarded somewhere in the rubble of Paco Station. But the sound it made, 750 rounds per minute for 23 minutes, covered John Ree long enough for one man to make it home.

That was the sound of improvisation under fire. The sound of a news boy from Texas who learned war faster than the enemy could adapt. The sound of 82 confirmed kills in 150 minutes with two weapons and five grenades. If you want to make sure Cleto Rodriguez and John Ree are not forgotten, hit that like button and subscribe.

These men fought with whatever they had. We remember them with whatever we

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load