July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not from fear, but from exhaustion. In front of him sits a 5- foot wide sphere covered in 32 precisely machined explosive blocks, and he’s drilling into them with a dentist’s drill.

The chemist turned bomb maker has discovered air pockets in the explosive lenses, tiny voids that could ruin everything. In less than 3 days, this device, nicknamed the gadget, will either compress a plutonium core to criticality and unleash the power of the atom, or it will scatter 5,300 lb of the world’s most expensive explosives across the New Mexico desert.

Kistiakowski fills each void with liquid explosive, working through the night. His colleagues watch nervously. One wrong move, one spark, and months of impossible engineering vanish in an instant. But here’s what makes this moment truly remarkable. Just 18 months earlier, every physicist at Los Alamos believed this design was impossible.

The idea of using explosions to create a perfect implosion, forcing divergent shock waves to converge with microscond precision, defied everything they knew about explosives. It was, as they said, going against nature. Today, you’re going to discover how a team of brilliant scientists solved one of World War II’s most complex engineering challenges.

Not with a single breakthrough, but through hundreds of failed experiments, revolutionary mathematics, and explosives that didn’t even exist at the war’s beginning. This is the story of the 32 explosive lenses that made the atomic age possible. Let’s rewind to spring 1944. Los Alamos’s scientific laboratory. The Manhattan project has been running for 2 years.

Thousands of people are working in secret facilities across America, racing to build an atomic bomb before Nazi Germany. The original plan seems straightforward. Use a gun type design. Fire one piece of uranium at another. Create a critical mass. trigger a nuclear explosion. Simple, elegant, it works beautifully for uranium 235. Then April 1944 arrives.

The first reactor produced plutonium samples come from Hanford. Alio Segre’s team tests it immediately. The results are catastrophic. Reactor bred plutonium contains plutonium 240, an isotope with a spontaneous fision rate five times higher than pure plutonium 239. Feed it through a gun type assembly and it will pre-detonate.

The nuclear material will blow itself apart before reaching full criticality. Instead of a 20 kiloton explosion, you’d get maybe 200 tons, a fizzle that wastes all that precious plutonium. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the laboratory’s director, faces an impossible choice. They can abandon plutonium entirely and bet everything on uranium 235, which Oak Ridge is producing at an agonizingly slow rate, or they can pursue an alternative method that most physicists consider science fiction. Implosion.

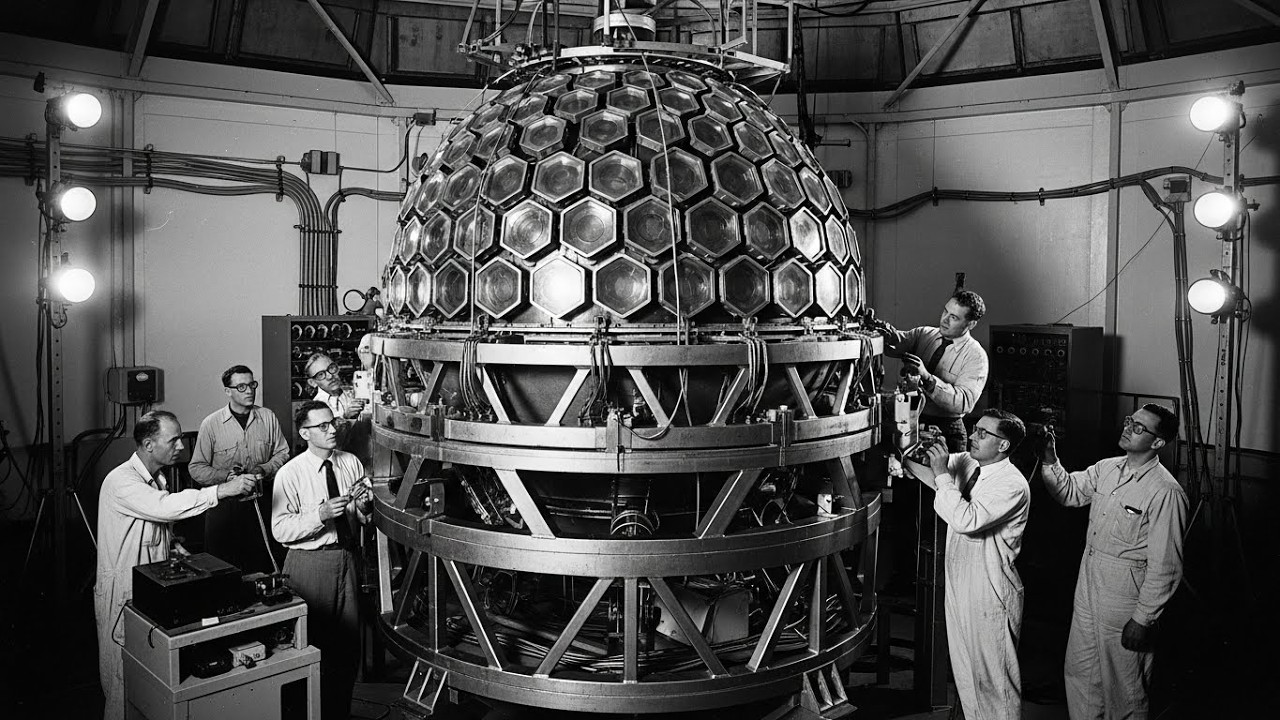

The concept sounds insane. Surround a subcritical sphere of plutonium with high explosives. Detonate them simultaneously from multiple points. create a spherically converging shock wave that compresses the plutonium core to twice its normal density in less than a microscond. Seph Netterme, a physicist from Caltech, has been tinkering with implosions since 1943.

His early experiments involve wrapping pipes with explosives and detonating them. The results are not promising. The cylinders emerge twisted, asymmetrical, looking like crushed beer cans. Nothing even remotely resembles the perfect spherical compression needed for a nuclear weapon. But what they didn’t know was that the solution would require abandoning traditional explosive science entirely and inventing a completely new field, precision explosives.

January 1944, James Conand, chairman of the National Defense Research Committee, makes a phone call to Harvard University. He’s looking for George Kistakoski. The Ukrainian-born chemist is already leading division 8 of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Explosives and Propellants. He knows more about high explosives than almost anyone in America, but he’s skeptical.

When Conan describes the implosion concept, Kistiakosski thinks it’s impossible. You’re asking explosives to do something they’re not designed to do, he tells Conan. Explosives diverge. They destroy. You want them to converge with microscond precision. Conan is persistent. By June 1944, Kistiakosski arrives at Los Alamos.

Within weeks, Oppenheimer promotes him to associate division leader of the explosives division. Nettermire, the original implosion advocate, is demoted to senior technical adviser. It’s a brutal move, but Oppenheimimer knows they’re running out of time. Kissakoski inherits a disaster. His team is conducting explosive test after explosive test.

Every result shows asymmetric compression. The plutonium sphere would emerge deformed, never reaching the density needed for criticality. Then a brilliant Hungarian mathematicianarrives at Los Alamos, John Vonoman. Vanimoman looks at the problem differently. Instead of trying to make a single explosive converge, what if they used multiple explosives with different detonation velocities? Think of it like an optical lens.

Light travels at different speeds through different materials. Glass bends light from a divergent beam into a convergent focal point. What if they could do the same thing with explosive shock waves? The concept of the explosive lens is born. But the real breakthrough came when British scientist James Tuck arrived in April 1944.

Tuck had spent years developing shaped charges for anti-tank weapons, explosives precision designed to focus energy into a single penetrating jet. He understood how to sculpt explosive geometry. Together, Vonoman and Tuck developed the mathematics. They need two explosives, one fast, one slow.

The fast explosive creates the initial divergent shock wave, but instead of letting it expand outward, they place slow explosive in a carefully calculated geometry. The shock wave hits the slow explosive at an angle, bends just like light through a lens, and redirects inward toward a single point. 20 hexagonal lenses, 12 pentagonal lenses, 32 total, arranged in a perfect sphere around the plutonium core.

On paper, it’s brilliant. In practice, they need to actually build it. And that means finding the right explosives. Here’s the problem. In 1944, the United States doesn’t have the explosives they need. For the fast explosive, they need something with a detonation velocity around 7.9 millimeters per microscond.

For the slow explosive, around 4.9 mm per microcond. And critically, they both need to be melt castable, allowing them to be poured into precise molds. TNT had been around since 1863. It’s stable, predictable, castable, but it’s too slow. Only 6.9 mm per microscond. Enter RDX, research department explosive. First synthesized by German chemist Gayorg Friedrich Henning in 1898.

RDX wasn’t practically useful until World War II. Britain’s Woolwitch arsenal developed production methods in the early 1940s. It’s 1.5 times more powerful than TNT, twice as powerful by volume with a detonation velocity of 8.7 mm per microcond. But there’s a problem. The British Woolwitch method of manufacturing requires 10 kg of nitric acid for every kilogram of RDX.

It’s expensive, impractical for mass production. Kistyakowski, remembering his days leading the explosives division, contacts Verer Bachmann at the University of Michigan. Bachmann has been working on a more efficient production method. Within months, he perfects what becomes known as the Bachmann process, combining Canadian techniques with direct nitration.

The Army hires Eastman Kodak to build a production facility in Tennessee. The Holston Army Ammunition Plant begins churning out RDX. Today, 80 years later, it’s still America’s primary supplier of military explosives. They mix 59.5% RDX with 39.5% TNT and 1% wax desensitizer. The result, composition B. Detonation velocity 7.

9 mm per microcond. Perfect for the fast explosive. But what about the slow explosive? Kistyakowski makes another call, this time to his former colleagues at the Explosives Research Laboratory in Brutin, Pennsylvania. He needs something much slower than TNT. Dr. Duncan McDougall and his team begin experimenting with barryium nitrate mixed with TNT.

Pure TNT isn’t slow enough, but barryium nitrate is almost inert. Mix them together, and you can tune the detonation velocity by adjusting the ratio. They settle on 76% barium nitrate 24% TNT. The result barl detonation velocity 4.9 mm per microcond. Now they have their materials but the biggest challenge was still ahead actually manufacturing 32 perfect explosive lenses each weighing over 80 lb with tolerances measured in thousandth of an inch. April 1945.

The X division casting facility at Los Alamos runs 24 hours a day. Imagine the challenge. You’re working with 5300 lb of high explosives. You need to melt them, pour them into molds, machine them to precise specifications, then assemble them into a perfect sphere. And you’re doing this while Nazi Germany might be attempting the same thing.

The composition B arrives as solid chips. Workers load them into steam jacketed kettles, heating them to 100° C. The TNT melts first, becoming a clear liquid. Then they slowly add water wet RDX, stirring continuously. Water evaporates. Finally, they mix in the wax desensitizer. The liquid explosive goes into molds, some hexagonal, some pentagonal, each carefully designed by von Newman’s mathematics.

They apply vacuum to remove air bubbles. Density is critical. Air pockets mean asymmetric detonation. The barl is trickier. Barerium nitrate doesn’t melt. It stays as fine powder suspended in molten TNT creating a thick slurry. They add 0.1% nitroc cellulose to reduce viscosity. Just before casting they add steroxy acetic acid to prevent cracking. Again, vacuum removes trappedgas.

Each lens is actually two pieces, a composition B outer section and a barl inner section. precision machined to fit together. The interface between them, where fast explosive meets slow explosive, is where the magic happens. The shock wave hits that boundary and bends inward, converging toward the center. But here’s what makes it truly remarkable.

They can’t test the actual lenses. They’re too expensive, too consuming to produce. Instead, they use surrogate materials, steel plates, aluminum spheres, and X-ray photography to watch shock waves propagate. Bruno Rossi, an Italian physicist who fled fascism, leads the diagnostic team. They develop multiple techniques. high-speed flash photography, rotating mirror cameras, the pin method, where metal pins connected to oscilloscopes are struck by the implosion providing timing data.

The most ingenious test is the Rala experiment, radioactive lanthnum. They place a gamma ray source at the center of a test assembly. As the shock wave compresses the metal sphere around it, the gamma rays are increasingly absorbed. Detectors positioned around the explosives measure the intensity changes, revealing the symmetry of compression.

Test after test, adjustment after adjustment. By summer 1945, they’ve conducted hundreds of experiments. And then Luis Alvarez solves the final puzzle. Even with perfect lenses, one problem remains. Timing. 32 explosive lenses mean 32 detonation points. If they don’t all fire within a few micros secondsonds of each other, the implosion will be asymmetric.

The plutonium core will squirt out the side instead of compressing uniformly. Traditional detonators use a primer cap, a small explosive charge that responds to heat or impact. But they’re inconsistent. Timing varies by tens of micros secondsonds. Completely unacceptable. Lewis Alvarez, an experimental physicist running the electronic detonators group, invents the solution.

Exploding bridgewire detonators. Here’s how they work. A thin wire, the bridge wire, is placed in contact with the explosive. When high voltage is applied, the wire doesn’t just heat up. It vaporizes explosively, creating a shock wave strong enough to initiate the main explosive charge. And critically, they’re fast and consistent.

Timing variation less than one microscond. But there’s another problem. Signal delay. Electricity travels fast but not instantaneously. If the wires from the firing unit to each detonator are different lengths, the signals arrive at different times. The solution is elegant. Make every wire exactly the same length.

The firing cables snake through the gadget’s interior, carefully measured to ensure simultaneous arrival. They even account for the thickness of insulation, which affects signal propagation speed. Two detonators per lens, 64 total, all connected to a single firing unit. If any single detonator fails, its backup ensures the lens still fires.

The entire system must function perfectly. There’s no room for error. There won’t be a second chance. Which brings us back to that night at McDonald Ranch House. Kistioski drilling out air pockets. The Trinity test is less than 3 days away. July 15th, 1945. The evening before Trinity. Oppenheimer is nervous.

The last Kuitz magnetic test showed anomalous results. Hans Btha spent all night reanalyzing the data, concluding it was an instrumental error, but doubt lingers. George Castia finds Oppenheimer at base camp. The physicists were very skeptical as to whether the lenses would work properly. Castiacowski later recalled, “I bet Oppenheimer quite a bit of my money, about $6 or $700 against $10, that the explosive part would work.

It’s not just money, it’s confidence.” Kistiakowski has spent 18 months perfecting these lenses. He knows they’ll work. July 16th, 1945. 4:00 a.m. A thunderstorm delays the test. Meteorologist Jack Hubard predicts a narrow weather window between 5 and 6 a.m. 5:29 a.m. Mountain wartime. Kenneth Banebridge presses the firing button.

64 exploding bridgewire detonators fire simultaneously. 32 explosive lenses convert divergent shock waves into a perfect converging sphere. The shock wave travels inward at 24,000 mph. It reaches the plutonium core, a 6.2 kg sphere about the size of an orange, and compresses it to twice its normal density in less than a microscond.

The plutonium goes super critical. 80 generations of neutron multiplication occur in less time than a human heartbeat. The temperature at the core reaches 10 million°. Energy equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT release in a fraction of a second. A flash of light brighter than a thousand suns illuminates the New Mexico desert.

10 m away, observers feel the heat on their faces. The shockwave arrives 40 seconds later. The mushroom cloud rises 7 mi into the atmosphere. The gadget has worked perfectly. Christyowski finds Oenheimer afterward. “I slapped Oppenheimer on the back and said, I won the bet,” he recalled. Oppenheimer paid up. But this was onlythe beginning.

3 weeks later, a device identical to the Trinity gadget called Fat Man is loaded onto a B-29 bomber called Box Car. On August 9th, 1945, it detonates over Nagasaki, Japan, bringing World War II to an end. The explosive lens concept didn’t end with Fat Man. Today, explosive lenses continue to serve critical roles.

The shaped charges Tuck originally developed are used in oil well perforation. Drilling companies use radial arrays of small shaped charges, typically 12 to 36 per meter, to create flow paths between wellbor and petroleum reserves. Military applications include anti-tank weapons where shaped charge jets can penetrate armor several times the charg’s diameter.

The modern SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule uses linear shaped charges, essentially one-dimensional lenses, to cleanly separate rocket stages during flight. The Holston Army Ammunition Plant, built to produce RDX for the Manhattan project still operates today. It remains America’s sole producer of RDX, HMX, and specialized plastic bonded explosives.

The Bachmann process developed under wartime pressure is still the standard manufacturing method. But perhaps the most important legacy is conceptual. Before 1945, explosives were crude tools for destruction. The Manhattan project transformed them into precision instruments. The field of detonation physics, understanding shockwave propagation, equation of state modeling, hydrodnamic instabilities emerged from these wartime efforts.

Modern nuclear weapons still use implosion designs based on the Trinity gadgets principles. Though modern explosives are safer and more powerful, the fundamental concept remains unchanged. use precisely shaped explosive lenses to convert divergent waves into spherical convergence. And it all started with a Ukrainian chemist who bet his money that 32 blocks of carved explosive could create a perfect implosion. He was right.

So, what did we learn today? The Trinity Gadgets 32 explosive lenses represent one of World War II’s most remarkable engineering achievements. Scientists had to invent new explosives, develop manufacturing processes that didn’t exist, create precision diagnostics to measure microscond phenomena, and solve mathematical problems that pushed the boundaries of what was possible in 1945.

But more than that, they transformed how we think about explosives. They proved that with enough precision, creativity, and determination, you can make even destructive forces serve controlled purposes. The 5,300 lb of composition B and barl surrounding that 6.2 kg plutonium core changed history. Not because explosives are powerful.

Humans have always known that, but because for the first time, explosives became precise. If you found this story fascinating, hit that subscribe button. Next week, we’re diving into another atomic age engineering mystery. How the code breakers at Bletchley Park built Colossus, the world’s first programmable computer to crack the Loren Cipher.

A story of vacuum tubes, paper tape, and mathematics that helped win the war. And if you want to explore more technical problem-solving stories from military history, check out our video on the Malberry Harbors, how engineers built two floating ports in nine months to supply the D-Day invasion. Link in the description. Thanks for watching.

This has been another deep dive into the technical brilliance that shaped our

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

America Lost Malaysian Tin in 1942 — So Engineers Reinvented The Soup Can DT

February 15th, 1942. Singapore. When British Lieutenant General Arthur Persal surrendered Singapore to Japanese forces, 85,000 Allied troops became prisoners…

End of content

No more pages to load