September 14th, 1944. RAF Northolt airfield, northwest of London. Wing commander Alan Wright stood in the operations room as the duty officer hung up the telephone receiver with unusual slowness. Outside the pre-dawn darkness still held, but something in the officer’s expression made Wright’s stomach tighten.

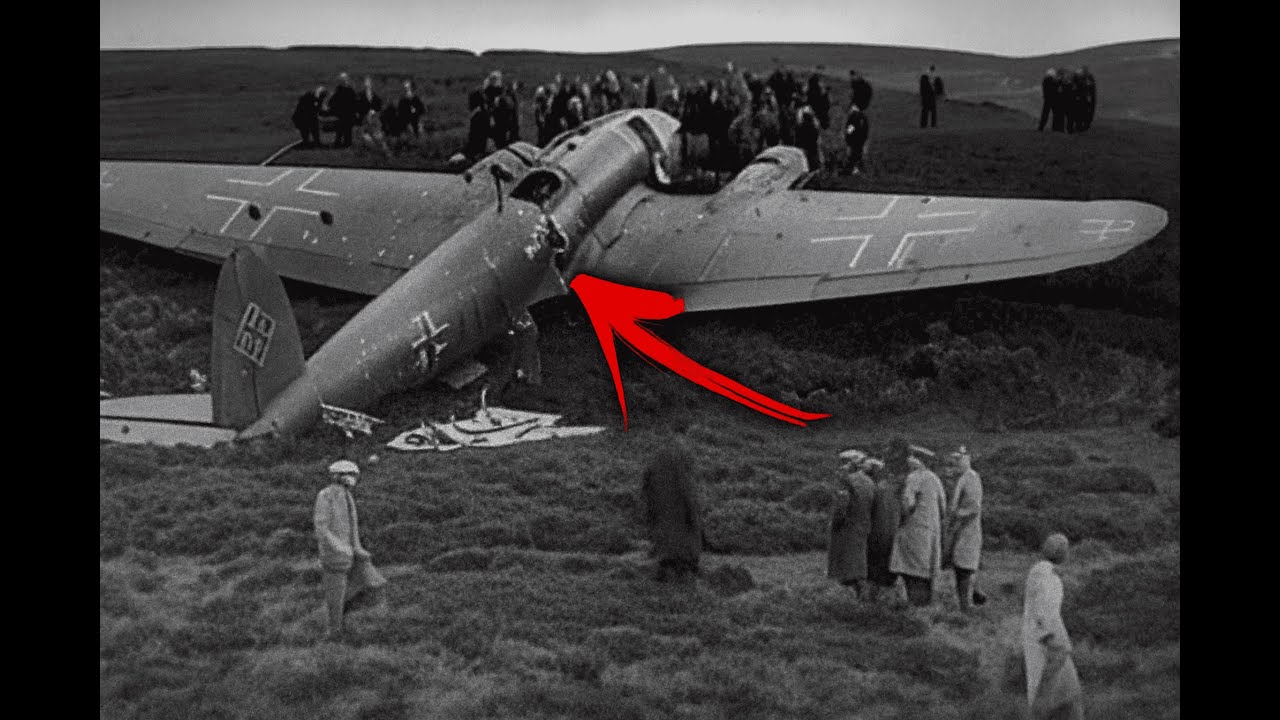

Another one, sir, the officer said quietly, crashed near Auxbridge. Henchel 126 reconnaissance markings. Wright walked to the plotting table where three other markers already sat. Four German scout planes in six nights. All within 15 mi of each other. All found in fields or forests with their cockpits torn open and their pilots dead.

No bullet holes, no burn marks, no explanation that made any sense. The first crash they’d attributed to engine failure. The second raised questions. By the third, intelligence officers were demanding answers. Now the fourth had fallen, and Wright could see the pattern emerging on the map, like some invisible drag net was sweeping German reconnaissance aircraft from the night sky.

What made it more unsettling was the silence. No anti-aircraft batteries had fired. No night fighters had scrambled. Observer posts reported hearing the German engines approach and then simply stop, followed by the distant sound of impact. It was as if something invisible was reaching up and plucking aircraft from the darkness.

Wright stared at the markers on the map, each representing a dead German pilot and a destroyed aircraft. Someone in the room muttered about gremlins. Another suggested mechanical sabotage, but Wright had been a pilot long enough to know that four identical failures in one week wasn’t coincidence. What RAPH investigators would discover in the wreckage would prove more effective than squadrons of night fighters and more terrifying to German air crews than any radarg guided interceptor Britain possessed.

For 2 years, German reconnaissance aircraft had operated over southern England with impunity. The Henchel H’s 126 and Feasler FI 156 Storch were purpose-built for lowaltitude observation work capable of flying at speeds as slow as 50 mph. While their observers photographed radar stations, airfields, and troop concentrations, their ability to loiter at altitudes between 500 and 2,000 ft made them nearly impossible targets for conventional defenses.

British anti-aircraft doctrine had been developed to counter high altitude bombers with heavy guns positioned to engage aircraft at 10,000 ft or above. The light automatic weapons that could threaten low-flying aircraft required visual acquisition of the target, and German reconnaissance pilots had learned to exploit the brief window between sunset and full darkness when they remained nearly invisible against the ground.

They flew without navigation lights, their darkly painted aircraft vanishing into the twilight. Night fighters presented their own challenges. The Bristol Bow Fighter and the Newer De Havlin Mosquito were formidable interceptors, but their minimum effective speed was nearly three times that of a slowly cruising reconnaissance aircraft.

Radar operators described the frustration of watching German scout planes appear on their screens, vectoring fighters to the contact, only to have the bow fighter overshoot before the pilot could even acquire the target visually. One mosquito pilot reported passing a fasler storch three times in a single engagement, unable to slow enough to bring his guns to bear without stalling.

The statistics told a grim story. Between June and September 1,942, German reconnaissance aircraft had flown an estimated 240 successful sorties over southern England, losing only six aircraft to all causes. British intelligence officers watched helplessly as Luftvafa photographic interpreters mapped every new radar installation within hours of its activation.

The Germans knew where fighter command was dispersing its squadrons. They knew which airfields were being expanded. They knew which convoy routes were being used. Squadron leader Richard Faulner, commanding a night fighter unit at Tangmir, described the situation in his operational diary with barely concealed frustration.

Chasing these bloody scouts is like trying to shoot a snail from a racing car, he wrote. We can see them on radar. We know they’re there, but by the time we slow enough to engage, they’ve disappeared into ground clutter or simply landed in the nearest field until we pass. The problem was tactical, technical, and psychological. Tactically, British defenses were configured for high-speed interception.

Technically, existing weapon systems couldn’t effectively engage such slowmoving targets at night. Psychologically, the continued success of German reconnaissance was demoralizing to RAF crews who felt impotent despite Britain’s growing technological advantage in radar and night fighting. What made the reconnaissance threat particularly acute in late summer 1942 was its role in the larger strategic picture.

Hitler had ordered preparations for operation celion to be maintained indefinitely, requiring regular intelligence updates on British coastal defenses. Simultaneously, the Luftwafa was planning retaliatory raids following RAF bomber commands thousand bomber attack on Cologne. German planners needed current reconnaissance photographs to select targets and plan approach routes.

Senior RAF commanders understood that every German reconnaissance sorty represented not just a violation of British airspace, but actionable intelligence that could cost Allied lives. Each photograph of a radar station meant German bombers could plot courses around detection. Each image of a fighter airfield meant Luftwafa planners knew where to expect interception.

The slow flying scouts weren’t dropping bombs, but they were enabling those who would. Several experimental solutions had been attempted and abandoned. Search light batteries tried to illuminate low-flying aircraft for anti-aircraft gunners, but the scouts simply descended below the beam’s effective range. Some fighter pilots advocated for slower biplane fighters to be retained for night reconnaissance interception, but production priorities made this impossible.

One particularly desperate proposal suggested training pilots to ram reconnaissance aircraft and bail out, but the obvious risks and questionable success rate prevented implementation. Luftwafa reconnaissance doctrine explicitly exploited British defensive limitations. Intelligence reports captured from a downed henchel 126 in August 1,942 included tactical guidance that bordered on contemptuous English night defenses are optimized for Chnel bombers and cannot engage low-speed observation aircraft.

The document stated maintain altitude below 2,000 m and air speed between 80 and 140 km per hour. Their fighters will overshoot. their anti-aircraft cannot track. German pilots flying these missions weren’t noviceses. Many were veteran Eastern Front observers who had conducted reconnaissance over Soviet positions where anti-aircraft fire was abundant and often accurate.

They knew how to read terrain, how to exploit twilight conditions and how to abort a sorty if conditions became unfavorable. Flight records showed most reconnaissance pilots had 500 or more operational hours. They were professionals conducting their work with methodical efficiency. The confidence extended to Luftwafa high command.

Airfleet 3 responsible for operations over England had lost so few reconnaissance aircraft that they considered the British night defense problem essentially solved from their perspective. Resources were being diverted from reconnaissance protection to bomber escort and ground attack roles.

After all, why allocate fighters to protect aircraft that weren’t being shot down? British attempts to counter the threat had become increasingly desperate and increasingly unsuccessful. In July, RAF Fighter Command had assigned an entire squadron of hurricanes to lowaltitude night patrol over suspected reconnaissance routes. In three weeks of intensive operations, they had achieved exactly two sightings and zero kills while consuming enormous quantities of fuel and pilot fatigue.

The squadron was reassigned to bomber escort duty. Ground observers reported the same frustration. Home Guard units and Royal Observer Corps posts could hear German engines passing overhead, could sometimes even see the dark silhouettes against the lighter sky, but possessed no weapons capable of engaging aircraft.

They could only watch, report grid coordinates to operations rooms and listen as the German scout departed unmolested. The psychological impact extended beyond military frustration. Civilians who had endured the Blitz took a certain pride in Britain’s increasingly effective night defense. The knowledge that German aircraft were still operating freely in British skies, even if they weren’t dropping bombs, undermined confidence in the RAF’s ability to protect the homeland.

Local newspapers in southern England occasionally published carefully worded stories about reconnaissance aircraft observed over the region. Though sensors prevented specific details, what neither German air crews nor British commanders fully understood was that a solution already existed. It wasn’t being developed in a laboratory or tested at a proving ground.

It had been proposed 3 months earlier by a civilian engineer whose background was in construction, not aviation. His memo had been filed, discussed briefly at a lower level planning meeting, and then effectively dismissed as impractical. The engineer’s name was Thomas Aldridge, and his idea involved piano wire, hydrogen-filled balloons, and a defensive concept so simple that experienced military officers had assumed it couldn’t possibly work until September 1942 when it started killing German pilots with mechanical efficiency. Before we

continue, I’d love to know where you’re watching from and what you know about unconventional air defense systems from World War II. Drop a comment below and let me know if you’d heard about balloon barrage modifications before. And if you’re enjoying these deep dives into the lesserknown innovations of the war, hit that subscribe button.

These stories take serious research to uncover, and knowing you’re out there makes tracking down these forgotten tactical developments worthwhile. Thomas Aldridge was not a military man, but he understood structural engineering. Before the war, his firm had specialized in suspension bridge design, work that required intimate knowledge of cable tension, load distribution, and material stress tolerances.

When the Ministry of Home Security contracted his company to assist with barrage balloon installations in 1940, Aldridge had approached the assignment with an engineer’s eye for optimization. The British barrage balloon program was already extensive by 1942. Nearly 2,000 balloons floated over London and key industrial centers.

Their steel cables designed to force German bombers to higher altitudes where anti-aircraft fire became more effective. The concept worked against level bombers, but reconnaissance aircraft simply flew under the balloon line, operating at altitudes where balloons weren’t deployed because they would interfere with friendly fighter operations.

In June 1942, Aldridge submitted a proposal that modified existing doctrine. Instead of raising balloons to 5,000 ft or higher, he suggested deploying smaller balloons at extreme low altitude between 500 and 1,000. 500 ft specifically along known reconnaissance routes. The revolutionary element wasn’t the balloons themselves, but the cables suspending them.

Standard barrage balloon cables were three 8- in steel, thick enough to be visible in daylight and designed to sever a bomber’s wing through sheer structural force. Aldridge proposed something different, piano wire, specifically high tensile steel wire measuring just 0.047 in in diameter, virtually invisible even in daylight and completely undetectable at twilight or night.

The military planning committee that reviewed Aldridge’s proposal raised immediate objections. Piano wire lacked the strength to damage a bomber. At such low altitudes, balloons would interfere with friendly aircraft operations. The cost of deploying additional balloon units was prohibitive. The memo was filed in the category of interesting but impractical civilian suggestions.

What changed the equation was wing commander right. After the fourth unexplained German reconnaissance crash in early September, Wright had requested all recent proposals related to lowaltitude air defense. Aldridge’s memo landed on his desk along with a dozen others. But Wright saw something the committee hadn’t.

German reconnaissance aircraft weren’t bombers. They weren’t heavily armored. They flew slowly with minimal structural reinforcement because their mission profile prioritized endurance and visibility, not survivability. Wright ran calculations. A Henchel 126 at 80 mph and countering a 0.047in piano wire wouldn’t hit it with enough force to sever the cable.

Instead, the wire would slice through fabriccovered control surfaces, tear through thin aluminum cowlings, and potentially enter the cockpit itself. The aircraft wouldn’t explode or even necessarily crash immediately, but the damage could be catastrophic. On September 7th, Wright obtained authorization for an experimental deployment.

12 small balloons were positioned along a fivemile corridor south of Auxbridge, each suspended by piano wire at staggered altitudes between 800 and 1,400 ft. The balloons were smaller than standard barrage types, measuring just 8 ft in diameter and filled with hydrogen rather than helium to achieve lift with minimal volume.

The piano wire was rated for 2,000 lb of tensil strength, more than adequate to hold the balloon, but thin enough to be essentially invisible. The deployment was rushed and imperfect. Some balloons had to be repositioned when they drifted out of the intended corridor. The piano wire installation required specialized handling because the thin cable could slice through leather gloves if tension was applied incorrectly.

Ground crews worked through the afternoon of September 7th to establish what Aldridge had started calling the neckline, though official documentation referred to it as experimental lowaltitude cable installation. One German reconnaissance aircraft operated on fairly predictable schedules with most sorties occurring in the hour after sunset when light levels made visual observation possible but provided cover from fighters.

At 1,847 hours on September 8th, an RAF observer post reported a German aircraft engine approaching from the south. The sound passed overhead, continuing northward along the expected route. At 1,851 hours, the engine note changed. Observers described it as a sudden roughness followed by a mechanical scream.

The sound lasted approximately 3 seconds before cutting off abruptly. Four minutes later, a home guard unit reported fire and wreckage 2 miles north of the last balloon position. RAF investigators reached the crash site by 2,000 hours. The aircraft was a Henchel 126 with reconnaissance markings. The pilot and observer were both dead, killed on impact.

What made the crash seemed distinctive was the damage pattern. The aircraft’s fabriccovered rudder had been sliced nearly in half by a clean cut running diagonally across the control surface. A second cut had severed three of the four bracing wires in the horizontal stabilizer. Most devastating, a piano wire had entered the cockpit through the side window, cutting through the pilot’s leather helmet and continuing forward through the instrument panel.

Wrapped around the tail section, nearly invisible against the dark metal, was 18 ft of 0.04 047in piano wire still attached to a small piece of balloon fabric. The investigators photographed everything, collected the wire for analysis, and filed an urgent report to Fighter Command headquarters. The following night, September 9th, two German reconnaissance aircraft approached the same corridor. Neither returned to base.

The wreckage of both was found within the experimental balloon line, both exhibiting similar damage patterns. By September 13th, five German reconnaissance aircraft had been destroyed by the piano wire installation. On September 14th, Wing Commander Wright was standing in the operations room examining markers for three more kills, all within the same defensive corridor.

The eighth German aircraft fell on September 16th, its pilot managing to radio a brief emergency transmission before his aircraft struck a wire and went down. The transmission partially intercepted by British listening stations consisted of four words before cutting to static wire. Unseen controls gone. Engineers and intelligence officers who examined the wreckage discovered something more elegant than a conventional weapon system.

The piano wire acted like a microscopic blade deployed across an entire corridor of airspace. At the wire 0.047 047 in diameter. It was effectively invisible from any aircraft cockpit at night, even in daylight. Pilots would have difficulty seeing it unless sunlight struck the wire at precisely the right angle. The physics of the engagement were brutally simple.

A Henchel 126 cruising at 80 mph covered approximately 117 ft pers. When any part of the aircraft contacted the piano wire, the wire didn’t snap because its 2,000lb tensil strength exceeded the force generated by the collision. Instead, the wire acted as a cutting edge, slicing through whatever material it encountered based on the pressure per square inch generated by the aircraft’s forward momentum.

Fabric control surfaces were particularly vulnerable. The Henchel 126’s rudder and elevators were fabric covered for weight savings. and piano wire could slice through them as easily as a razor through paper. In three of the eight crashes, investigators found that control surfaces had been severed or severely damaged, making the aircraft effectively unflinable.

Two pilots had died trying to control aircraft with no rudder authority. The second failure mode was structural. Piano wire cutting through wing bracing or tail structure created cascading failures. One fasler storch had suffered catastrophic tail separation when a wire cut through three fuselage stringers, the structural members that gave the tail section rigidity.

The pilot had no warning before his aircraft literally came apart in flight. The most disturbing failure mode from the German perspective involved direct cockpit penetration. In two cases, piano wire had entered the cockpit area through side windows or gaps in the fuselage. The extreme thin diameter of the wire, combined with the aircraft’s forward momentum, meant the wire could penetrate leather helmets, instrument panels, and even seatbacks.

One pilot had been killed instantly when wire entered through the right cockpit window and struck his head. His observer, sitting behind him, survived the initial strike, but died in the subsequent crash. Wing Commander Donald Finlay, assigned to analyze the tactical implications, wrote in his assessment that the piano wire system represented a passive defense mechanism operating with mechanical consistency regardless of visibility, radar coverage, or fighter availability.

Unlike anti-aircraft guns that required target acquisition or fighters that needed vectoring, the piano wire simply existed in the airspace. Waiting. The psychological impact on German reconnaissance crews began manifesting within days. Luftwafa signals intelligence intercepted and decrypted at Bletchley Park showed reconnaissance sorty cancellations increasing dramatically in midepptember.

Flight logs captured from a downed aircraft later in the month revealed that pilots were refusing to operate below 2,500 ft over southern England, effectively moving above the altitude where low- speeded reconnaissance was most effective. What made the system particularly valuable was its scalability.

Each balloon installation cost approximately 47 pounds, roughly 120th the cost of a single radar installation and requiring only a ground crew of three to maintain. The piano wire itself was readily available from British steel manufacturers who had been producing it for musical instruments and industrial applications.

Unlike complex weapon systems requiring specialized manufacturing, the neckline could be rapidly deployed using existing materials and minimal training. By October 1942, 37 separate piano wire installations had been deployed around probable German reconnaissance routes. Intelligence reports suggested German photographic reconnaissance over southern England had declined by 73% compared to August figures.

Luftwaffa commanders, unaware of the specific defensive mechanism, attributed losses to improved British night fighter tactics or new radar systems, neither of which was accurate. The Germans were flying higher, slower, and far less frequently. The invisible neckline had achieved what squadrons of Knight fighters could not. The piano wire defensive system remained in operation through the spring of 1,943, ultimately credited with destroying or damaging 23 German reconnaissance aircraft.

An additional seven probable kills were recorded in cases where aircraft were seen or heard in distress, but wreckage was not recovered. The killto cost ratio was extraordinary. 23 confirmed kills at a total deployment cost of approximately 1,600, making it the most economically efficient air defense system Britain employed during the war.

Thomas Aldridge received no public recognition during the war years. His contribution classified under regulations governing defensive installations. In 1947, he was quietly awarded the Order of the British Empire for services to national defense, though the citation made no specific mention of the piano wire system. He returned to bridge engineering and died in 1968, having given only one interview about his wartime work to a military historian researching unconventional defense measures.

The German Luftwaffa never fully understood what was killing their reconnaissance aircraft. Postwar examination of captured German intelligence files showed that analysts attributed the losses to multiple causes. New anti-aircraft proximity fuses, improved night fighter tactics, possible radarg guided ground weapons, and mechanical failures.

The actual mechanism, nearly invisible piano wire suspended from small balloons, was not documented in German intelligence assessments. The simplicity of the system worked as camouflage. German analysts expected sophisticated technology and overlooked the possibility of such a primitive solution.

The tactical impact extended beyond direct kills. German reconnaissance over southern England declined from an average of 42 sorties per month in summer 1942 to fewer than eight per month by January 1943. This intelligence blackout came at a critical period when the allies were preparing for the eventual invasion of Europe. German commanders operating with outdated information about British force dispositions made planning decisions based on reconnaissance photographs 6 or 8 months old.

The piano wire concept influenced post-war thinking about airspace denial. During the Korean War, United States Air Force planners briefly considered deploying similar systems against low-flying North Korean POE, two biplanes conducting harassment raids. The concept was rejected not because it wouldn’t work, but because jet aircraft operating in the same airspace would be at risk from their own defenses.

The fundamental principle that invisible barriers could deny airspace to slowmoving aircraft remained sound. Wing Commander Wright, promoted to group captain by 1945, later wrote that the piano wire system demonstrated how engineering creativity could overcome tactical problems that conventional military thinking couldn’t solve.

“We were trying to shoot mosquitoes with artillery,” he noted in his memoirs. Aldridge suggested a net. Sometimes the simplest solution is the one nobody in uniform considers because we’re trained to think in terms of firepower rather than physics. The last piano wire installation was dismantled in May 1945. The balloons were deflated.

The wire was recycled for industrial use and the ground crews were reassigned. No memorial marks where they stood. War drives innovation not just in weapons but in thinking. The piano wire defense succeeded because it abandoned conventional assumptions about what an air defense system should look like. No radar, no guns, no explosives, just tension, geometry, and the lethal precision of a wire invisible until the moment of impact.

The German pilots who died flying into those wires weren’t victims of superior technology. They were defeated by superior adaptation, by an engineer who looked at an unsolvable problem and asked a different question. Not how do we shoot them down, but how do we make the airspace itself lethal? The answer cost 47 pounds per installation and changed how both sides thought about lowaltitude operations.

Thomas Aldridge never flew an aircraft and never fired a shot in combat. Yet, his contribution saved an unknown number of lives by denying German intelligence the photographs they needed to plan effective bombing raids. The reconnaissance aircraft he helped destroy represented eyes that would have guided hundreds of bombers to British targets.

Sometimes the most effective weapon isn’t the one that makes the loudest noise or carries the biggest warhead. September 14th 1,942 Four German pilots dead in crashes no one could explain. By month’s end, eight aircraft destroyed by an invisible barrier that existed in three dimensions but couldn’t be seen, heard, or detected until it was too late.

One navigation error would have been chance. Eight aircraft, one defensive system, and a lesson in how physics defeats confidence. Sometimes the most dangerous weapons are the ones you never see coming. If you found this story as fascinating as I did researching it, I’d appreciate if you’d like this video and subscribe to the channel.

There are dozens more untold stories from World War II’s unconventional innovations that deserve to be remembered, and I’ll be bringing you a new one every week. What lesserk known defensive system or tactical innovation should I cover next? Let me know in the comments below.

News

“Don’t Leave Us Here!” – German Women POWs Shocked When U.S Soldiers Pull Them From the Burning Hurt DT

April 19th, 1945. A forest in Bavaria, Germany. 31 German women were trapped inside a wooden building. Flames surrounded them….

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft DT

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory in Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

Inside Ford’s Cafeteria: How 1 Kitchen Fed 42,000 Workers Daily — Used More Food Than Nazi Army DT

At 5:47 a.m. on January 12th, 1943, the first shift bell rang across the Willowrun bomber plant in Ipsellante, Michigan….

America Had No Magnesium in 1940 — So Dow Extracted It From Seawater DT

January 21, 1941, Freeport, Texas. The molten magnesium glowing white hot at 1,292° F poured from the electrolytic cell into…

They Mocked His Homemade Jeep Engine — Until It Made 200 HP DT

August 14th, 1944. 0930 hours mountain pass near Monte Casino, Italy. The modified jeep screamed up the 15° grade at…

Beyond the Stage and the Stadium: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Unveil Their Surprising New Joint Venture in Kansas City DT

KANSAS CITY, MO — In a world where celebrity business ventures usually revolve around obscure crypto currencies, overpriced skincare lines,…

End of content

No more pages to load