At 5:47 a.m. on January 12th, 1943, the first shift bell rang across the Willowrun bomber plant in Ipsellante, Michigan. 42,000 men and women moved through the gates. They didn’t come to eat. They came to build the weapon that would end the war. But without food, the weapon would never leave the ground. What followed wasn’t just logistics.

It was survival architecture on an impossible scale. Ford’s cafeteria system became the second largest food operation in America, surpassed only by the US army itself. It consumed more resources daily than the entire Nazi Vermacht used to feed its eastern front. And it was run by a woman most of history forgot.

If you’re drawn to untold stories of innovation under pressure, this is exactly where you need to be. Hit that subscribe button now because the stories we uncover here don’t just inform, they reveal the invisible machines that built victory. The statistics were never supposed to work. 12 cafeterias scattered across a single production complex.

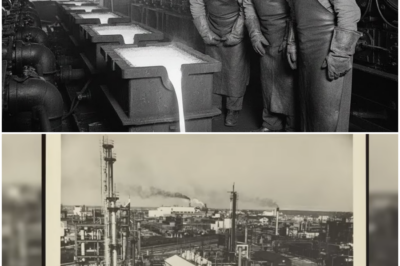

Each one a self-contained fortress of steel counters, industrial stoves, and walk-in refrigerators the size of small houses. 4,000 meals served every 15 minutes during peak hours. Not 4,000 over a lunch period, 4,000 every quarter hour, like a metronome of human hunger ticking against the clock of war production. 18 tons of meat delivered daily, arriving in refrigerated trucks that had to navigate security checkpoints, unload in designated zones, and disappear before the next shift change.

gridlocked the service roads. 90,000 eggs cracked before dawn. Each one a fragile calculation in a system that couldn’t afford a single morning’s failure. Bread baked in shifts so relentless the ovens never cooled below 400°. Their heating elements glowing like the forges that shaped bomber fuselages three floors above.

Coffee brewed in vats large enough to drown a man. percolating constantly in 40-gallon batches that were consumed and replaced before they had time to go stale. This wasn’t a cafeteria. It was a supply chain operating under wartime rules, feeding a workforce larger than most American cities, with margins of error measured not in percentages, but in whether people collapsed at their stations or kept working.

If the food stopped, the bombers stopped. If the bombers stopped, men died over Germany, over the Pacific, over cities whose names most of these workers couldn’t pronounce, but whose liberation depended on aluminum wings they’d never touch. The kitchen had become a weapon, and nobody knew it yet. Not the workers who ate there, not the managers who approved budgets, not even the woman who would spend three years proving it was true.

The woman who built it had never managed anything larger than a country club dining room. Her name was Edith Clark, though Ford’s personnel files listed her as EM Clark to avoid questions from union reps who didn’t believe women could command industrialcale operations. She’d been hired in 1941 to oversee a single employee cafeteria at the River Rouge plant.

1,200 workers, predictable hours, standard menu rotation, meatloaf on Tuesdays, fish on Fridays, apple pie when sugar rations allowed. It was institutional food done competently, which was all Ford expected. Then Willow Run opened and the numbers became incomprehensible. Clark was given three weeks to design a feeding system that didn’t exist anywhere in civilian America.

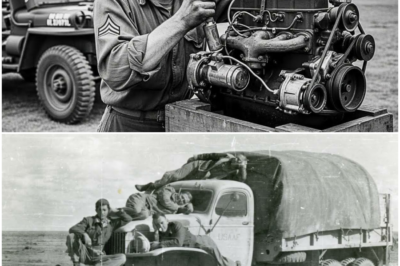

No precedent, no manual, no second chance. She started by visiting army mess halls at Fort Kuster and Camp Livingston, standing in serving lines with young men about to ship overseas, watching how sergeants moved proteins and starches with assembly line efficiency. What she learned terrified her. Military kitchens operated on rationing, repetition, and the assumption that soldiers would eat anything or starve.

Meals were designed for nutritional sufficiency, not satisfaction. Calories met minimum requirements. Taste was irrelevant. Morale wasn’t a line item on the menu. Factory workers wouldn’t tolerate that. They’d walk out. They’d call union reps. They’d slow production through a thousand small acts of resistance that no foreman could prove, but everyone would feel.

Production would collapse, not from sabotage, but from silent refusal. Morale was an ingredient she couldn’t omit. It wasn’t written in any manual, but every conversation she’d had with line workers told her the same truth. Feed them like prisoners and they’ll work like prisoners. Feed them like human beings and they might just build the thing that ends the war.

Her first decision violated every efficiency model Ford had ever published. She refused to centralize. 12 cafeterias meant 12 supply chains, 12 kitchens, 12 management teams. Ford’s engineers called it wasteful. Clark called it necessary. Workers on the far end of the mileong assembly building wouldn’t walk 20 minutes for a meal.

They’d bring cold sandwiches, eat them in 6 minutes, and return to the line exhausted. She neededfood close, fast, and hot. So she scattered the kitchens like outposts across a battlefield. Each one had to function independently. Each one had to survive if the others failed. This wasn’t redundancy. It was resilience.

The kind armies learned through defeat. She was building it before the first plate was served. The engineering problems appeared immediately. Willow Run ran three shifts 24 hours non-stop. The cafeterias never closed. Breakfast blurred into lunch. Dinner became midnight steak and eggs for the graveyard crew.

Peak demand hit at shift changes when 18,000 workers flooded the lines simultaneously, expecting to be fed and back at their stations within 30 minutes. Standard industrial kitchens couldn’t handle the surge. Clark studied train station restaurants. stadium concessions and military field kitchens. She borrowed techniques from each and invented what none had needed.

Conveyor systems for dirty trays, pre-portioned meals wrapped in wax paper, modular serving stations that could expand or contract based on crowd density. Every decision was a bet against chaos, and chaos was always waiting. The supply chain was where the impossibility became visible. 18 tons of beef arrived daily, delivered in refrigerated trucks that had been diverted from civilian grocery routes.

Rationing meant every pound required federal approval. Clark had to prove to the war production board that feeding willowrun workers was as essential as feeding soldiers. She submitted production data, absenteeism reports, and physician testimonies about malnutrition related accidents on the line. It took 4 months.

When approval came, it arrived with conditions, no waste, every ounce accounted for, monthly audits, one violation, and the allocation would be revoked. She built a tracking system more rigorous than Ford’s parts inventory. Meat arrived pre- butchered. Bones went to rendering plants for glycerin used in explosives. Fat became soap for decontamination stations.

Scraps fed hog farms that supplied the next week’s pork. Nothing left the system. Waste wasn’t just inefficiency. It was sabotage. Eggs presented a different crisis. 90,000 per day delivered in crates stacked floor to ceiling in refrigerated warehouses. Breaking them by hand would have required a team working full shifts just to prep breakfast.

Clark contacted a machinery supplier in Detroit who’d been designing automated egg cracking systems for large bakeries, but had never scaled them to this volume. She gave them two weeks and unlimited access to one of Ford’s machine shops. They delivered a contraption that looked like an assembly line for fragility.

Eggs rolled single file onto padded conveyors, struck a blade at precise angles, and emptied into chilled vats without a single shell fragment. It cracked 1,200 eggs per hour. Clark ordered six units. They ran 18 hours a day. When one broke, the others compensated. Redundancy again. She was learning the language of war without ever wearing a uniform.

Bread was the silent crisis. Each cafeteria served 2,200 loaves daily. Not sandwich bread, not dinner rolls. full onepound loaves that workers could take to their stations, break apart during 10-minute breaks, and consume without needing plates or utensils. Industrial bakeries couldn’t meet the demand without cutting civilian supply, which would have triggered rationing protests, congressional inquiries, and public relations disasters Ford couldn’t afford.

while presenting itself as a patriotic manufacturing partner. Clark couldn’t wait for federal intervention. Bureaucracy moved in months. She had weeks. She installed commercial ovens in each cafeteria basement, massive steel chambers with rotating racks that could bake 60 loaves simultaneously, and hired bakers directly from closed down neighborhood shops who’d lost business to wartime shortages and ingredient restrictions.

These men worked alone, underground in 120° heat, shaping dough in darkness, while bombers took form in the light above them. They never saw the planes. They never walked the assembly line. But every loaf they baked kept a riveter at their station 10 minutes longer. Kept a machinist’s blood sugar stable enough to read micrometers accurately.

Kept a welder’s hands steady enough to seal fuel tanks that wouldn’t leak at 20,000 ft. Margin of survival measured in minutes and flour. One baker, a Polish immigrant named Ysef Zarnetski, worked 73 consecutive days without missing a shift. His hands developed burns that never fully healed. His lungs filled with flower dust that doctors later said contributed to the pneumonia that killed him in 1954.

When asked why he pushed himself past human limits, he said his brother was a pilot in the RAF, flying Spitfires over the channel. And every time he thought about stopping, he imagined his brother’s face and kept needing. The bread wasn’t food. It was a promise that someone somewhere was still fighting, and that the fight matteredenough to destroy yourself, keeping it supplied.

Coffee became a morale calculation. Ford’s management wanted to eliminate it to save costs and shipping weight. Clark refused. She’d interviewed workers during her first week and learned that coffee wasn’t refreshment. It was the pause that prevented mistakes. A machinist grinding turbine components couldn’t afford distraction. 10 seconds of focus lost could ruin a part worth $600 and three days of labor.

coffee gave them that 10 seconds back. She ordered industrial percolators capable of brewing 60 gallons per cycle. The coffee was strong enough to taste like punishment and weak enough to drink by the quart. Workers complained, then they drank it anyway. Taste wasn’t the point.

The warmth in their hands, the bitterness waking them up at 3:00 a.m. The shared moment at the N. Those were the reasons production stayed steady. Clark defended coffee like it was ammunition. In a way, it was. The human cost appeared in places no report could measure. Kitchen staff worked conditions worse than the assembly line.

Heat that made breathing feel like drowning. Noise that left ears ringing for hours after shifts ended. Grease fires that erupted without warning when fat dripped onto heating elements designed to run 24 hours without cooling. Scalding water that sent workers to the infirmary with secondderee burns on hands and forearms.

and the unrelenting pressure of 18,000 people who expected food exactly on time every time, regardless of equipment failures, supply shortages, or the fact that human beings have limits that machines don’t respect. Turnover was brutal. Clark lost a third of her workforce in the first 6 months. Women quit after 3 weeks.

men transferred to the assembly line where the work was hard, but at least you could see what you were building. She couldn’t offer higher wages. Ford’s union contracts fixed pay rates across all departments, and kitchen work was classified at the same level as janitorial services, which insulted every person who’d ever orchestrated a meal service for 4,000 people, while equipment malfunctioned and supplies ran short.

So, she offered something rarer than money, respect. She instituted a rule that floor supervisors could never yell at kitchen staff, a policy that got her called soft by Ford’s operations managers, who believed fear was the only effective motivator. Mistakes were addressed privately in offices with explanations rather than accusations. Exceptional work was recognized publicly.

Names called out during shift briefings. Written commenations placed in personnel files that actually mattered during promotion reviews. She rotated shifts so no one worked graveyard duty for more than 2 weeks straight. Because she’d learned that human circadian rhythms weren’t suggestions, they were biological limits.

And violating them consistently produced the kind of exhaustion that caused accidents. And she did something no other Ford manager had ever done. Something that scandalized the executive dining room and made her a legend among the workers. She ate with them. Every day Clark took her lunch in the kitchen, sitting on a flower sack or a stool near the dish line, eating the same food the workers ate from the same plates, listening.

She learned who had sick children at home and couldn’t afford the doctor visits that would diagnose the pneumonia before it became fatal. whose husband was overseas somewhere in the Pacific, missing for three months with no word from the War Department about whether he was alive, captured, or buried in an unmarked grave on an island whose name would never appear in newspapers, who hadn’t slept because of night terrors from the noise, the constant industrial roar that followed them home and invaded their dreams until they woke up

screaming about assembly lines that never stopped moving. She couldn’t fix those problems. She didn’t have the authority or the resources, but she could make sure their work wasn’t the thing that broke them. That the 8 or 10 or 12 hours they spent in her kitchens didn’t add to the weight already crushing them.

Attrition slowed, not because conditions improved. The heat was still unbearable, the hours still inhuman, the pressure still relentless, but because someone finally noticed they were human. And in a war that treated people like components in a machine, that recognition was more valuable than wages.

The system’s first real test came in March 1943. A rail strike in Ohio delayed shipments across the Midwest. A labor action triggered by wage disputes that had nothing to do with war production, but everything to do with the fact that railroad workers were dying from exhaustion at rates that made frontline combat look survivable. Supply lines dependent on predictable schedules began to fracture.

Willowr run system designed for daily deliveries with zero buffer inventory because warehouse space was allocated to aircraft parts began to starve. Meattrucks didn’t arrive. Produce rotted in a warehouse two states away. Visible through chainlink fencing, but untouchable due to jurisdictional regulations that prevented Ford trucks from crossing state lines to retrieve their own supplies.

By the third day, cafeteria managers were serving fried eggs and toast for every meal, breakfast, lunch, and dinner. The same plate, the same nutritional emptiness. Workers started bringing bag lunches again. Cold sandwiches wrapped in wax paper. Thermoses of weak coffee. Apples bruised from being carried in coat pockets. Absenteeism spiked.

Production dropped 4%, a number that sounds minor until translated into bombers. 4% meant 37 fewer aircraft completed that week. 37 crews without planes. 37 missions delayed or cancelled. 37 moments where air superiority faltered because men in Michigan couldn’t get pot roast. Clark knew she had 72 hours before the plant’s output fell below contractual minimums, triggering financial penalties and possible federal intervention that would replace Ford’s management with government appointees who’d never run anything larger than a

regional post office. She made a call to a black market food broker in Detroit, a man named Vincent Chelini, whose name appeared in FBI files under suspicions of rakateeering, but whose deliveries had never once failed to arrive on time. She’d been told to avoid him by every Ford accountant, every legal adviser, every manager who valued their career over their conscience.

He could deliver, but the prices were triple the federal ceiling, paid in cash with no receipts and no questions. Clark didn’t hesitate. She approved the purchase using discretionary funds allocated for facility repairs, then buried the expense across 6 months of budgets under line items labeled plumbing maintenance, electrical upgrades, and pest control.

The food arrived at midnight in unmarked trucks driven by men who didn’t speak and didn’t wait for signatures. By the next morning, the cafeterias were serving pot roast, mashed potatoes, and green beans. Workers noticed the quality was better than usual. No one asked questions. No one wanted to.

The strike ended 4 days later when federal mediators forced a compromise. Clark never mentioned what she’d done. The expense reports were audited twice and passed both times because the auditors were looking for theft, not patriotism disguised as embezzlement. But the kitchen staff knew. They’d watched the trucks unload.

They’d seen Clark standing in the loading bay at 1:00 a.m. supervising men who looked like they’d kill someone for asking their names. Loyalty wasn’t built through speeches. It was built through action under pressure. Through the willingness to risk everything, including federal prosecution, to make sure the people who trusted you didn’t go hungry while building the weapon that would end the worst war in human history.

If these stories matter to you, if you believe that history is written by the people no one thought to remember, then subscribe now. These narratives don’t go viral, they go deep, and that’s exactly why they matter. By mid 1944, the cafeteria system had become a self- sustaining machine. Each location operated with near zero waste, militarygrade punctuality, and morale metrics that puzzled Ford’s efficiency analysts.

Workers weren’t just fed, they were sustained. The difference was invisible on spreadsheets, but obvious on the floor. Accident rates dropped. Sick days declined. Productivity per worker hour increased by margins small enough to seem coincidental, but consistent enough to prove causation.

The food wasn’t just fuel. It was a signal that someone cared whether they lived or died. In a factory building machines designed to kill, that signal mattered more than anyone admitted. Clark’s system caught the attention of military logistics officers studying industrial food service for overseas operations. In August 1944, two army quarter masters visited Willow Run to observe cafeteria operations during a shift change, the most chaotic and revealing moment in any food service operation.

They wore civilian clothes to avoid disrupting worker morale, but their posture gave them away. Military men always stood differently. They watched 18,000 workers move through the lines in 26 minutes. A choreographed chaos that looked like disorder, but functioned with the precision of a drill ceremony. Every worker knew their station.

Every server knew their portions. Every line moved at exactly the same speed, regulated not by supervisors, but by mutual understanding that delay meant someone behind you didn’t eat. The quarter masters reviewed Clark’s supply chain documentation, waste management protocols, and staffing rotations, spending 4 hours in her basement office reviewing binders thick enough to stop rifle rounds.

One officer, a colonel named Raymond Hutchkins, who’d coordinated supply drops over Normandy and watched men starve because weather delayed shipments by 6 hours, askedClark a single question. How much of this could be replicated in a field environment? She answered, “Honestly, none of it.” Her system depended on infrastructure, refrigeration that required constant electrical power, transportation networks that assumed roads existed and weren’t cratered by artillery.

A stable workforce that showed up every day because their homes weren’t being bombed and their families weren’t fleeing invasion. Remove any one of those variables and the model collapsed into the chaos she’d spent three years preventing. The colonel nodded. He’d expected that answer.

Then he asked a second question, and his voice changed. It became quieter, more personal. If you had to feed this many people with half the resources, what would you cut first? Clark didn’t hesitate. Variety. She’d serve the same meal three times a day if it meant everyone ate. Beans and rice, potatoes, and spam. Whatever could be stored without refrigeration, cooked with minimal fuel, and consumed without complaint because the alternative was starvation. Morale would suffer.

But starvation was worse. You could rebuild morale. You couldn’t resurrect the dead. The colonel wrote that down in a pocket notebook, his handwriting small and precise. Three months later, that logic appeared in revised Army feeding protocols for the Pacific Theater, distributed to every quartermaster corps officer from Brisbane to Manila.

Clark was never credited. Her name didn’t appear in the manual. She didn’t expect it to. The work was the point, not the recognition. But every soldier who ate a hot meal on Okinawa, every Marine who got beans and rice on Ewima instead of cold rations, owed their survival to a conversation in a basement office in Michigan, where a woman explained that feeding people wasn’t about abundance.

It was about not letting them die while they fought. The German comparison wasn’t propaganda. It was math verified by post-war analysis of captured Vermached logistics documents and quartermaster records seized by Allied forces in 1945. At its peak in 1944, the Nazi Vermacht allocated approximately 12 tons of food daily to feed frontline divisions on the Eastern Front, supplemented by irregular supply lines that depended on forced requisition from occupied territories, a system that was simultaneously a war crime and a logistical strategy.

German soldiers ate what they could steal from Ukrainian farms, Polish villages, and Russian towns, taking grain, livestock, and stored vegetables at gunpoint, while the people who’d grown that food starved in sellers and barns. It was conquest as food service. Barbaric, yes, but also practical in the way that evil often is when divorced from morality.

Ford’s Willowrun cafeterias consumed 18 tons daily under controlled continuous conditions with zero supply interruption, zero theft, and zero reliance on violence. The difference wasn’t abundance. America had abundance. The difference was precision. The ability to move food from farms to factories to plates without a single link in the chain breaking without a single shipment arriving spoiled, without a single worker going hungry because someone upstream made a mistake or a truck broke down or a warehouse burned.

German logistics relied on conquest and improvisation. American logistics relied on railroads, refrigeration, and a woman who understood that feeding people wasn’t about dominance or force. It was about systems thinking, about redundancy, about the unglamorous truth that wars aren’t won by the side with the best soldiers or the most tanks.

They’re won by the side whose supply chains don’t collapse under pressure. The Nazis fed armies to sustain territorial conquest. An empire built on blood and theft that could only exist as long as there were new territories to plunder. Ford fed workers to sustain production. A machine that could theoretically run forever as long as farms kept growing food and trains kept moving it.

One system built empires. The other built bombers. Only one of them won the war. And it wasn’t the one that relied on stealing bread from starving children. Clark’s personal toll remained unspoken, invisible to everyone except the people who knew what it cost to hold a system together through will alone when every structural support was failing.

She worked 16-hour days, 7 days a week for three consecutive years. Not occasionally, not during crises, every single day from January 1943 through August 1945, arriving at 5:00 a.m. before the first shift bell, and leaving after 900 p.m. when the night crew had settled into rhythm, and the last supply delivery had been checked against inventory sheets.

She missed her daughter’s high school graduation, sending a telegram of congratulation that arrived 3 days late because she’d forgotten to mail it until the ceremony was already over. She didn’t attend her father’s funeral in Ohio. A man who’d raised her alone after her mother died of influenza in 1919 and who taught her that work wasn’tsomething you did for money.

It was something you did because people depended on you showing up. He died believing she didn’t care enough to say goodbye. She did, but 42,000 people needed to eat that day, and grief is a luxury that systems can’t afford. Her marriage dissolved quietly in 1945, not from infidelity or anger, but from absence so complete it became a form of abandonment.

Her husband, Daniel Clark, a tool and die maker at River Rouge, who worked 60-hour weeks himself and understood the demands of war production, filed for separation in July, citing irreconcilable differences. The real difference was simple. She’d chosen the work over everything else, over dinners together, over conversations that didn’t involve production schedules, over the idea that two people could build a life that wasn’t entirely consumed by the machinery of national survival.

He wasn’t wrong to leave. She’d stopped being a wife the moment she took the job. Not because she wanted to, but because 42,000 people depended on a system that would collapse if she stopped managing it for even a week. There was no one else. Ford’s management had never trained a replacement because they’d never believed the system would last beyond the war.

and training someone meant admitting a woman had built something they couldn’t replicate, which violated assumptions they weren’t willing to question. Clark knew the system wouldn’t last. Wartime always ends, but until it did, she couldn’t let it fail. The cost of that knowledge was her entire personal life, every relationship, every moment of peace, every possibility of being something other than the woman who fed Willow Run.

She paid it without complaint, then spent the rest of her life wondering if the trade had been worth it. If the bombers she’d helped build had saved more lives than her absence had destroyed. The math never balanced. It wasn’t supposed to. War doesn’t offer fair trades. It offers impossible choices and then judges you for whichever one you make. The end came abruptly.

On August 15th, 1945, Japan surrendered. Within 72 hours, Willow Run’s production schedule was cut by 60%. Workers were furoughed in waves. Cafeterias that had served 4,000 meals per shift now served 400. By October, eight of the 12 locations had closed permanently. Equipment was sold, staff laid off, supply contracts canled.

The system Clark had built to feed an army dissolved in six weeks. She was offered a position managing food services at Ford’s corporate headquarters in Dearbornne. A quieter job, regular hours. She declined. The work no longer required what she’d learned to give. She left Ford in November 1945 with a severance check, a letter of recommendation, and no public recognition of what she’d built.

Her name appeared in no histories of Willow Run, no documentaries about the homeront, no retrospectives on industrial food service. She became a footnote in a war that produced 10 million footnotes, most of them graves. She spent the next 30 years managing hospital cafeterias in Ann Arbor, applying the same principles on a smaller scale, precision, respect, resilience.

She never spoke publicly about Willow Run. When a local historian contacted her in 1974 for an oral history project on wartime production, she declined the interview. Her reason, written in a brief letter, was simple. The work had been necessary, not heroic. She’d done what the moment required, then moved on.

Heroism, she believed, was a word used by people who hadn’t been there. The real story wasn’t triumph. It was endurance. And endurance didn’t make good copy. She died in 1981, 3 weeks after her 79th birthday. The obituary in the Ann Arbor News mentioned her hospital work and her family. Willow Run wasn’t listed.

Neither was the fact that for 3 years she’d fed more people daily than any woman in American history. The cafeteria buildings were demolished in 1958 when the Willowrun site was converted into an automotive parts warehouse. No plaques were installed, no memorials erected. The ovens, the conveyors, the industrial percolators, all of it sold as scrap metal or repurposed for postwar diners and factory lunchrooms across the Midwest.

Pieces of the system Clark built still exist, scattered and anonymous in places that have no idea where they came from. A diner in Flint still uses one of her original coffee earns. A high school cafeteria in Toledo serves food on trays that once fed B-24 Riveter crews. The machinery survived. The memory didn’t.

But the logic endured. Modern industrial food service from tech campus cafeterias to offshore oil rig galleys operates on principles Clark established under wartime pressure. distributed kitchens, waste tracking, redundant supply chains, morale-based menu design. None of these concepts were codified in her time, but all of them trace back to decisions she made when failure meant letting people starve while building the weapon that would end the worst war in human history. Shedidn’t invent industrial food service.

She perfected it under conditions no one else had ever faced. Then she walked away because the work was done and recognition was never the point. The final image is a photograph, undated, found in a box of personnel records donated to the University of Michigan archives in 1996. It shows a woman in a plain dress and apron standing beside an industrial oven, her face partially obscured by shadow.

No name is written on the back. No context provided, but the oven’s manufacturer’s plate is visible. Blahett Model J48. The same model installed in Willowrun’s cafeteria 7 in 1943. The same model that baked bread for 16,000 workers per day at the height of bomber production. The woman in the photograph is almost certainly Edith Clark, and she’s not smiling.

She’s looking at something beyond the camera, beyond the frame, with the expression of someone who knows exactly how much weight she’s carrying, and exactly how little credit she’ll receive for not dropping it. That look is the story. The rest is just numbers. If this story mattered to you, if you believe the invisible architects of victory deserve to be remembered, then subscribe because every week we uncover another name history tried to forget, and we make sure it’s spoken again.

The kitchen fed 42,000 workers daily. It consumed more food than an entire German army. It was run by a woman whose name appeared in no history books. And it worked. Not because it was easy, but because someone refused to let it fail. That refusal is what won wars, not tanks, not bombs, not speeches. The quiet decision made every morning at 5:47 a.m.

to keep the system running one more day. That’s the history worth remembering. And if we stop telling it, it dies with the people who lived it. The war ended, the ovens went cold, the workers went home, and the woman who fed them disappeared into a life that never asked her to be extraordinary again. She didn’t mind. Extraordinary had nearly killed her.

What she’d learned was simpler, harder, and more truthful than any medal or monument could convey. You don’t build victory through genius. You build it through endurance. One shift, one meal, one day at a time until the work is done. Or you are. Clark chose the work. The work chose history. And history as always forgot to say thank.

The silence that follows is the sound of 42,000 people who never went hungry because one woman decided that feeding them mattered more than being remembered for it. That silence is the loudest truth this war ever produced. And it echoes still in every cafeteria, every kitchen, every person who believes that the work, the real work is keeping people alive long enough to finish what they started.

Clark understood that the war proved her right. And then, as wars do, it moved on. But the lesson remains, invisible, essential, unbreakable. Just like the woman who taught

News

“Don’t Leave Us Here!” – German Women POWs Shocked When U.S Soldiers Pull Them From the Burning Hurt DT

April 19th, 1945. A forest in Bavaria, Germany. 31 German women were trapped inside a wooden building. Flames surrounded them….

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft DT

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory in Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

America Had No Magnesium in 1940 — So Dow Extracted It From Seawater DT

January 21, 1941, Freeport, Texas. The molten magnesium glowing white hot at 1,292° F poured from the electrolytic cell into…

They Mocked His Homemade Jeep Engine — Until It Made 200 HP DT

August 14th, 1944. 0930 hours mountain pass near Monte Casino, Italy. The modified jeep screamed up the 15° grade at…

Beyond the Stage and the Stadium: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Unveil Their Surprising New Joint Venture in Kansas City DT

KANSAS CITY, MO — In a world where celebrity business ventures usually revolve around obscure crypto currencies, overpriced skincare lines,…

Midnight Mercy Dash: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce’s Secret Flight to Dallas to Support Patrick Mahomes After Career-Altering Surgery DT

In the high-stakes world of professional sports and global entertainment, true loyalty is often tested when the stadium lights go…

End of content

No more pages to load