January 26th, 1945 1447 Holtz, France. Second Lieutenant Audi Murphy stood on the engine deck of a burning M10 Wolverine tank destroyer and fired a Browning M2HB 50 caliber machine gun at German infantry approaching from three sides. The M10 beneath his boots carried 54 rounds of 762 mm ammunition and 750 L of diesel fuel. One penetrating hit and the vehicle would detonate.

Murphy weighed 50 kg. He was 165 cm tall. He was 19 years old. Six Panza Fors and 250 Gabbergs Jagger veterans from the Arctic were advancing across open snow toward his position. Behind him, 18 men from Company B, First Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment, had retreated to a treeine 150 m distant.

Those 18 men were all that remained of the 120 who had entered combat 48 hours earlier. Murphy’s parents were dead. His father had abandoned the family. His mother died when Murphy was 16. He had 12 siblings. He fed them by hunting rabbits in East Texas with a 22 rifle. The Marines rejected him in 1942 for being too short. The paratroopers rejected him for weighing too little.

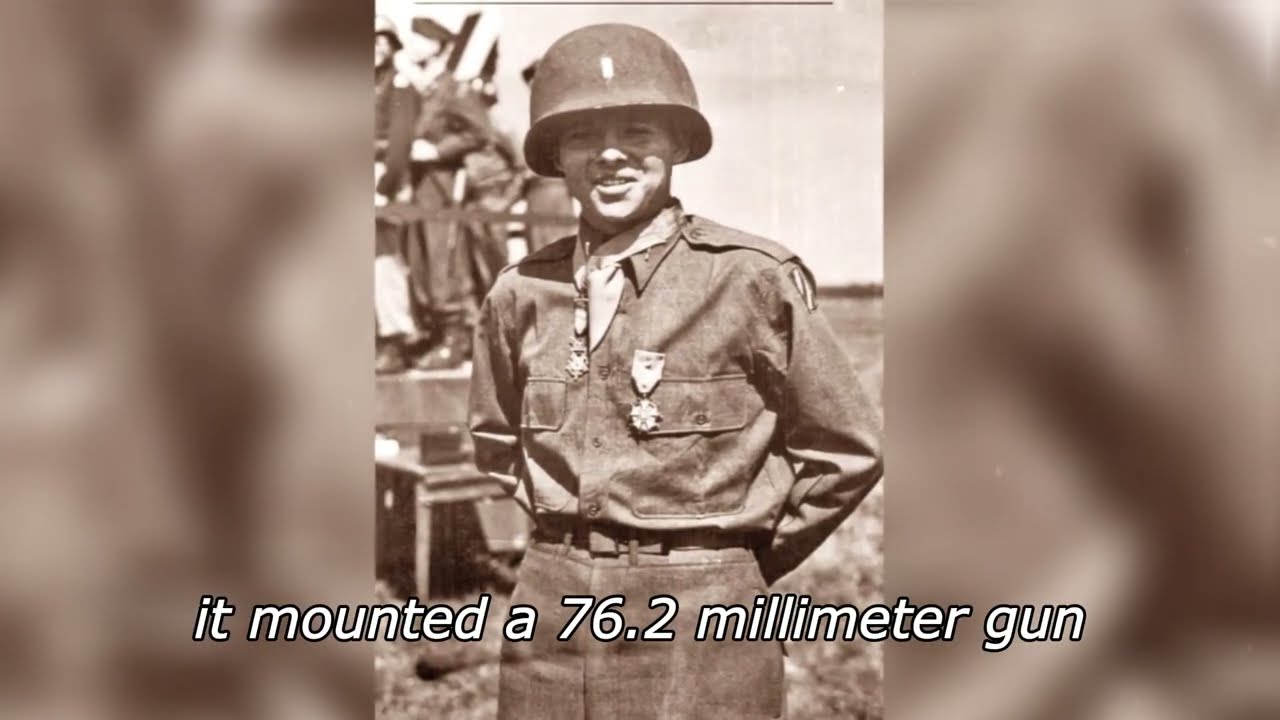

The Army accepted him, but his platoon thought he would die in his first engagement. He did not die. By January 26th, 1945, Murphy had killed Germans in Sicily, at Anzio, and across southern France. He had earned the Distinguished Service Cross, two silver stars, one Bronze Star, and two Purple Hearts. He was the youngest second lieutenant in his regiment.

On this day, Murphy would earn the Medal of Honor by holding a position no other man in his company believed could be held. The citation would state he killed or wounded approximately 50 Germans in one hour while exposed to fire from three sides. Germans closed to within 10 yards before Murphy cut them down. How a 19-year-old orphan with a fifth grade education stopped six panzas and 250 veteran infantry using a weapon mounted on a vehicle designed to explode at any moment is what this story documents. Murphy was born June 20th, 1925 in

Kingston, Texas, sharecropper family. His father left when Murphy was young. His mother died in 1941. Murphy became the head of a household of 12 children at age 16. He fed them by hunting. East Texas in the depression offered no employment for a boy with no education. Murphy became expert with a rifle out of necessity. He trapped rabbits. He shot squirrels at distance.

He learned to judge wind, to control breathing, to wait for the right moment. These were not military skills. They were survival skills. But survival skills translated directly to combat effectiveness. When Murphy finally entered the war in 1942 at age 17, Murphy attempted to enlist. The Marines rejected him.

Height requirement 5’6 in minimum. Murphy measured 5’5 in. The paratroopers rejected him. Weight requirement 120 pounds minimum. Murphy weighed 110 pounds. The army accepted him with reservations. His baby face made him look 14. His drill instructors doubted he would survive basic training. His fellow recruits thought he would die in his first firefight. Murphy did not argue. He trained.

He qualified on the M1 Garand. He learned infantry tactics. He deployed to North Africa in 1943 with Company B 15th Infantry Regiment, Third Infantry Division. Sicily, July 1943. Murphy’s first combat. Company B assaulted German positions near Polarmmo. Murphy saw a German Panza advancing on his squad.

No anti-tank weapons available. Murphy grabbed a belt of grenades and crawled to within 30 m of the tank. He threw four grenades at the tracks. The tank stopped. The crew evacuated. Murphy shot two of them with his garand. His platoon leader recommended him for a bronze star. Murphy was 18 years old. Anzio, January 1944.

Company B fought for four months in static positions against entrenched German defenders. Murphy learned to operate in conditions where visibility was measured in meters and survival was measured in hours. He became proficient at reading terrain, at identifying covered approaches, at moving without sound. Southern France, August 1944.

Operation Dragoon. Murphy’s platoon was pinned down by German machine gun fire near Ramatu. Murphy flanked the position alone. He killed six Germans, wounded two, and captured 11. His commanding officer recommended him for the Distinguished Service Cross. The citation was approved.

Murphy was promoted to staff sergeant. October 1944. Lommet Quarry, Cluri River Valley. Murphy led an assault on German positions. He exposed himself to enemy fire to direct his squad’s advance. He killed multiple Germans at close range. He was awarded his first Silver Star. 5 days later, during operations near the Moselle River, Murphy again led from the front. His squad destroyed German fortifications and captured a strategically important hill.

He received his second silver star. Murphy had been wounded twice by this point. Once by mortar shrapnel in September 1944 near Vleure. Once by sniper fire to the hip on October 26th, 1944. Each time Murphy refused extended medical evacuation, he returned to his unit within days.

On January 14th, 1945, Murphy was promoted to second left tenant. He was 19 years old. He had been in combat for 18 months. He had seen more fighting than officers twice his age. January 1945, the Kulmar pocket. German forces held a salient in Alsace, Eastern France. The pocket contained approximately 50,000 German troops from the 19th Army. Allied command ordered the pocket eliminated.

The mission was designated operation cheerful. The third infantry division was assigned to assault the northern edge of the pocket. Murphy’s company B was tasked with seizing the Bad Reedvier, a forested area near the village of Holtzvier. The terrain was flat agricultural land now covered in snow. Visibility was poor.

Temperature ranged between -20 and -25° C. The Germans defending the area were from the second Gberg’s division, mountain troops who had fought in Finland and Norway. These were not garrison soldiers. They were experienced winter warfare specialists. January 24th, Company B began its assault. 120 men advanced into the Badavier.

German resistance was immediate and coordinated. Machine gun positions, mortars, and pre-registered artillery. The forest was a prepared defensive zone. Company B fought for 2 days. On January 25th, the company emerged from the forest with 18 men still combat effective. 102 men killed or wounded in 48 hours.

Murphy was one of the 18. On the morning of January 26th, Company B was ordered to hold a defensive position along a tree line west of Haltzere. The position overlooked an open snow-covered field approximately 400 meters wide. On the far side of the field was another tree line. German positions.

Two M10 Wolverine tank destroyers were assigned to support company B. The M10 weighed 29,600 kg. It mounted a 76.2 mm gun. It carried 54 rounds of ammunition, 300 rounds of bank 50 caliber for the roof mounted Browning M2HB, and 750 L of diesel fuel. The armor was thin, 51 mm on the glacis, 25 mm on the sides and rear.

The M10 was designed for mobility, not survivability. Murphy established his command post approximately 40 m forward of the tree line. He had a field telephone connected to the 39th Field Artillery Battalion. Murphy had learned to call artillery precisely. He could adjust fire by sound and by observing impact.

He did not need a forward observer. He could direct the guns himself. At 1,400 on January 26th, German artillery began impacting around Company B’s positions. The barrage lasted approximately 10 minutes. Shells landed in the tree line in the open field near Murphy’s command post. The ground was frozen.

Explosions created larger fragmentation patterns than they would have in soft earth. Murphy crouched in a shallow foxhole and waited. The telephone line remained intact. When the barrage lifted at 1410, silence followed for approximately 30 seconds. Then Murphy heard engines, diesel engines, heavy vehicles. He looked across the field toward the German treeine 300 m distant.

Six shapes emerged from the forest. Panza fours or threes. Murphy could not distinguish at that distance through the snow. The vehicles advanced in a line. Behind them, approximately 50 meters back, came infantry, white winter camouflage uniforms. Murphy counted quickly. More than 200 men, probably 250. The Germans were executing a combined armor infantry assault.

Murphy assessed the situation. Company B had 18 men, two M10s, small arms, and access to artillery support. The Germans had six tanks, and 250 infantry. The math was not favorable. If Company B remained in position, they would be overrun within minutes. Murphy made his decision.

He picked up the telephone and called his company. His order was direct. fall back to the tree line. Prepare defensive positions. I will stay forward and direct artillery fire. His men hesitated. Several asked if Murphy was coming with them. Murphy’s response, “Someone needs to call the artillery. Go.” The 18 men withdrew. Murphy remained at his command post alone. He called the 39th Field Artillery Battalion. Fire mission.

Enemy armor and infantry advancing. Range 300 meters. The guns responded. Murphy heard the shells incoming. The first salvo landed approximately 200 m in front of the advancing panzas. Murphy adjusted. Drop 50 m. Shift right 20 m. The second salvo was closer. Explosions among the German infantry. Murphy saw men fall.

The panzas continued advancing. The German infantry spread out using shell craters for cover. Murphy continued adjusting fire. The artillery killed Germans, but it did not stop the advance. At 14:15, the M10 positioned 50 m from Murphy’s command post was hit. A German 75 mm shell struck the M10’s right side.

The armor was only 25 mm thick on the flanks. The shell penetrated. Fire erupted immediately. The diesel fuel ignited. Black smoke poured from the engine compartment. The five-man crew evacuated within seconds. They ran toward the tree line where company B had withdrawn. The M10 continued burning. Murphy watched the vehicle.

The Browning M2HB machine gun was still mounted on the open turret. The gun appeared undamaged. Murphy looked at the advancing Germans. The Panzas were now approximately 180 m away. The infantry was at 150 m and closing. Murphy calculated. If the Germans reached the tree line, company B would be overrun. 18 men with rifles could not stop 250 infantry supported by armor.

The only weapon capable of engaging multiple targets at that range was the 50 caliber on the burning M10. Murphy left his command post. He sprinted 50 m to the M10. Heat radiated from the vehicle. Flames were visible inside the crew compartment. The ammunition for the 762 mm gun was stored in racks below the turret.

If those rounds cooked off, the M10 would explode. Murphy climbed onto the vehicle. The metal was hot. It burnt his hands through his gloves. He reached the turret. The Browning M2HB was mounted on a pedestal. The gun weighed 382 kg. A belt of 300 rounds was fed from an ammunition box. Murphy checked the weapon. It was loaded. The belt was intact. The gun was functional.

Murphy positioned himself behind the Browning. Below him, 54 rounds of 762 mm ammunition. Around him, 750 L of burning diesel. In front of him, six panzas and 250 German infantry. Murphy gripped the butterfly trigger and aimed at the advancing soldiers. At 1417, Murphy opened fire.

The Browning M2HB fired at a rate of 450 to 600 rounds per minute. The 50 BMG cartridge had a muzzle velocity of 890 m/s. Every fifth round was a tracer. Red lines streaked across the snow toward the German infantry. Murphy aimed center mass on the lead soldiers. The first German fell, the second, the third. The Browning’s recoil pushed against Murphy’s shoulder. He braced himself against the turret and continued firing.

Short bursts, six to eight rounds per target. The Germans were at 150 m. Effective range for the M2HB was 1,800 m. At 150 m, Murphy could not miss. German soldiers fell in clusters. The advancing line wavered. Return fire began immediately. German MG42 machine guns, MP40 submachine guns, and KR 98K rifles all directed fire at Murphy’s position. Bullets struck the M10’s hull.

The sound was sharp and metallic. Ting, ting, ting. Murphy was exposed from three sides, front, left flank, right flank. He rotated the Browning, engaging targets across a 180° arc. The first wave of Germans took casualties and stopped advancing. The Panzas, now without close infantry support, halted their advance. Murphy had been firing for approximately 30 seconds.

He had killed or wounded at least 15 Germans. The initial assault was disrupted. At 1425, the Germans regrouped and launched a second wave. This attack was more cautious. The infantry used shell craters and snow bankanks for cover. They advanced in shorter bounds, moving from position to position. Murphy adjusted his fire. He no longer had clear targets standing in the open.

He had to anticipate movement. When a German rose to advance, Murphy fired. The 50 caliber rounds penetrated light cover easily. Wooden debris, snow, equipment. The bullets created massive wound cavities. Men hit by 50 BMG rounds did not survive. Murphy identified leaders, German sergeants directing squads, officers pointing with map cases.

He targeted them first. When the leader fell, the squad hesitated. That hesitation created opportunity. Murphy engaged the rest of the squad while they were disorganized. The heat from the burning M10 intensified. Murphy felt the souls of his boots beginning to melt. Smoke obscured his vision intermittently.

He fired through the smoke, aiming at muzzle flashes and movement. The ammunition belt fed smoothly. Murphy did not count rounds, but he estimated he had fired approximately 100. That left 200 in the belt. The second German wave faltered. 20 to 30 more casualties. The panzas remained at 120 m, unable to advance without infantry support. At 1435, the Germans attempted a third attack.

This assault came from multiple directions simultaneously. One squad advanced from the left flank, another from directly ahead. A third attempted to circle right. Murphy was now fighting in three directions. He prioritized threats. The right flank was most dangerous because it offered an approach that would put Germans behind him.

Murphy swung the Browning 90° to the right and engaged the flanking squad at 30 m. He fired a sustained burst. Eight Germans fell. The rest retreated. Murphy rotated back to the front. Germans were advancing at 50 m. He fired short, precise bursts, five to six rounds per target. The Browning was overheating. The barrel glowed faintly. Murphy ignored it. The ammunition belt was running low.

He estimated 40 rounds remaining. He began firing more conservatively. Single shots for targets beyond 50 m. Short bursts for targets closer. At 1442, Murphy saw movement at his right flank again. A German squad had crawled through a drainage ditch. They were 20 m away. Murphy had not seen them approach.

The squad leader stood to fire. Murphy rotated the Browning. He had eight rounds left in the belt. He fired. The squad leader fell. Two more Germans fell. The rest retreated back down the ditch. At that moment, a German mortar round exploded 5 m from the M10. Shrapnel struck Murphy’s left leg. The pain was immediate and sharp.

Blood soaked through his trousers. Murphy did not stop firing. At 1447, a final group of Gibger reached 10 yards from the M10, 9 m. Murphy could see their faces. Fear, determination, exhaustion. He fired the last rounds in the belt. Three Germans fell at point blank range. The Browning clicked empty. Murphy pulled the trigger again. Nothing. The belt was expended.

Murphy released the butterfly trigger. The browning was silent. Smoke continued to pour from the M10 beneath him. The vehicle had been burning for more than 30 minutes. The 76 2 mm ammunition had not detonated, but that was luck, not design. Murphy climbed down from the turret. His hands were burned.

His left leg was bleeding. He limped 50 m back toward the treeine. German infantry were withdrawing. Without the concentrated fire from Murphy’s position, they had attempted to press the attack, but the panzas were already reversing. Armored vehicles without infantry support do not advance into uncertain terrain. The Germans pulled back toward their original treeine.

The field was littered with bodies. Murphy counted quickly. At least 60 visible. More were likely wounded and had crawled to cover. Murphy reached the American tree line at 1450. His men were waiting. A medic ran forward. Murphy waved him off. “Where’s my company?” Murphy asked. The medic pointed. Murphy found his 18 men in defensive positions along the treeine. They stared at him. No one spoke.

Murphy picked up a field telephone and called the 39th Field Artillery. He requested fire on the retreating Germans. The guns complied. Shells impacted across the field, targeting the withdrawing infantry. Murphy then turned to his company. His order was direct. We’re going back. His men hesitated.

They had just survived an assault by overwhelming force. Now Murphy wanted to attack. Murphy did not repeat himself. He picked up an M1 carbine from a wounded soldier and began walking back toward the field. Company B followed. 18 men in a skirmish line. Murphy led the advance. Artillery fire walked ahead of them 100 m forward. German stragglers attempted to regroup.

Murphy identified them and called artillery on their positions. Company B advanced 200 m beyond Murphy’s original command post. They reached the edge of the German tree line. The Germans had completely withdrawn. Murphy ordered his men to halt and consolidate. They returned to the American treeine.

At 1600, Murphy finally accepted medical treatment. The shrapnel wound in his left leg required 12 stitches. The medic removed metal fragments and sutured the wound closed. This was Murphy’s third purple heart. The battalion commander arrived shortly after. He asked Murphy what he had been thinking. Murphy’s response was simple.

Someone had to stay. The recommendation for the Medal of Honor was submitted on January 27th. Murphy was evacuated to a field hospital on January 28th. He returned to duty 2 weeks later. On June 2nd, 1945, Lieutenant General Alexander Patch, Commander of the Seventh Army, personally presented Murphy with the Medal of Honor.

The ceremony was held on the French Riviera. Murphy’s citation was read in front of the entire Third Infantry Division. The numbers were documented. Six tanks repelled, 200 to 50 infantry engaged, approximately 50 killed or wounded by Murphy’s fire alone. One hour under fire from three sides, Germans closed to within 10 yards. Murphy continued fighting despite a leg wound.

Murphy was promoted to first lieutenant 3 weeks after Holtzphere. He was removed from frontline duty and assigned to regimental headquarters. The war in Europe ended in May 1945. Murphy returned to the United States. He was 20 years old. Murphy’s combat record was extraordinary by any measure. Nine campaigns, 27 months overseas, 241 enemy soldiers killed according to official credit, 33 decorations, the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, two silver stars, the Legion of Merit, two bronze stars with V device for valor, three purple hearts, five French decorations, including the

Leon Donur, The Belgian cuadigar Murphy was the most decorated American combat soldier of World War II. He had enlisted at age 17, weighing 110. He had been rejected by two branches of the military. He had been told by his own platoon that he would not survive. He proved them all wrong. After the war, Hollywood discovered Murphy.

His story was too compelling to ignore. a baby-faced orphan from Texas who became a one-man army. In 1955, Murphy starred in the film adaptation of his autobiography, To Hell and Back. He played himself. The film was one of the highest grossing of the decade. Murphy’s portrayal was understated. He did not dramatize.

He simply showed what had happened. Audiences were stunned. On May 28th, 1971, Murphy died in a plane crash near Brush Mountain, Virginia. He was 45 years old. The aircraft crashed in bad weather. There were no survivors. Murphy’s funeral was held on June 7th, 1971.

He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, section 46, with full military honors. Thousands attended. His headstone is one of the most visited at Arlington. People come from across the country to pay respects. Not because Murphy was a movie star, because Murphy was a soldier who refused to let his men die when he could do something about it.

The Medal of Honor citation states that Murphy’s actions saved Company B from annihilation. 18 men lived because one 19-year-old lieutenant climbed onto a burning tank destroyer and fired a 50 caliber machine gun at an enemy force more than 10 times his size. Murphy did not call himself a hero. In interviews after the war, he deflected praise. He said he did what anyone would have done, but anyone did not do it.

Murphy did. The question Colonel Ferry asked John George after Guadal Canal applies equally to Murphy. Could he train other men to do what he had done? The answer is no. What Murphy did at Holtzphere was not a teachable skill. It was not about marksmanship or tactics or equipment.

It was about the refusal to accept defeat when accepting defeat was the rational choice. Murphy saw 250 Germans advancing on 18 Americans and decided the Germans would not pass. That decision made in a frozen field in Alsace in January 1945 is why Murphy’s name is remembered today. If this story moved you the way it moved us, hit that like button.

Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Murphy didn’t just save 18 men that day. He showed that courage doesn’t come from size or age, but from refusing to let your men die alone. Drop a comment and tell us where you’re watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada? Our community stretches across the entire world.

You’re not just a viewer, you’re part of keeping these memories alive. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure Audi Murphy doesn’t disappear into silence.

News

The Kingdom at a Crossroads: Travis Kelce’s Emotional Exit Sparks Retirement Fears After Mahomes Injury Disaster DT

The atmosphere inside the Kansas City Chiefs’ locker room on the evening of December 14th wasn’t just quiet; it was…

Love Against All Odds: How Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Are Prioritizing Their Relationship After a Record-Breaking and Exhausting Year DT

In the whirlwind world of global superstardom and professional athletics, few stories have captivated the public imagination quite like the…

Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Swap the Spotlight for the Shop: Inside Their Surprising New Joint Business Venture in Kansas City DT

In the world of celebrity power couples, we often expect to see them on red carpets, at high-end restaurants, or…

The Fall of a Star: How Jerry Jeudy’s “Insane” Struggles and Alleged Lack of Effort are Jeopardizing Shedeur Sanders’ Future in Cleveland DT

The city of Cleveland is no stranger to football heartbreak, but the current drama unfolding at the Browns’ facility feels…

A Season of High Stakes and Healing: The Kelce Brothers Unite for a Holiday Spectacular Amidst Chiefs’ Heartbreak and Taylor Swift’s “Unfiltered” New Chapter DT

In the high-octane world of the NFL, the line between triumph and tragedy is razor-thin, a reality the Kansas City…

The Showgirl’s Secrets: Is Taylor Swift’s “Perfect” Romance with Travis Kelce a Shield for Unresolved Heartbreak? DT

In the glittering world of pop culture, few stories have captivated the public imagination quite like the romance between Taylor…

End of content

No more pages to load