In January 1942, Boeing plant 2 in Seattle, which was supposed to churn out B17 flying fortresses at a pace that could darken German skies, looked more like an industrial traffic jam than a weapon of war. 63 incomplete bombers sat on the assembly line. Each one a promise America hadn’t yet fulfilled.

While the Army Air Forces had ordered 3,615 for the year, and Boeing had delivered a mere 9, a failure that enraged General Henry Hap Arnold, who warned executives in a fiery meeting that without bombers, the strategic bombing campaign would stall, leaving American soldiers to face a fully entrenched Nazi war machine.

And every day of delay meant more German factories producing more planes, more ships sunk in the Atlantic, and more time for Hitler to consolidate his grip on Europe. The problem wasn’t manpower. The plant had hired over 30,000 workers in 6 months. Many of them women who had never set foot in a factory before.

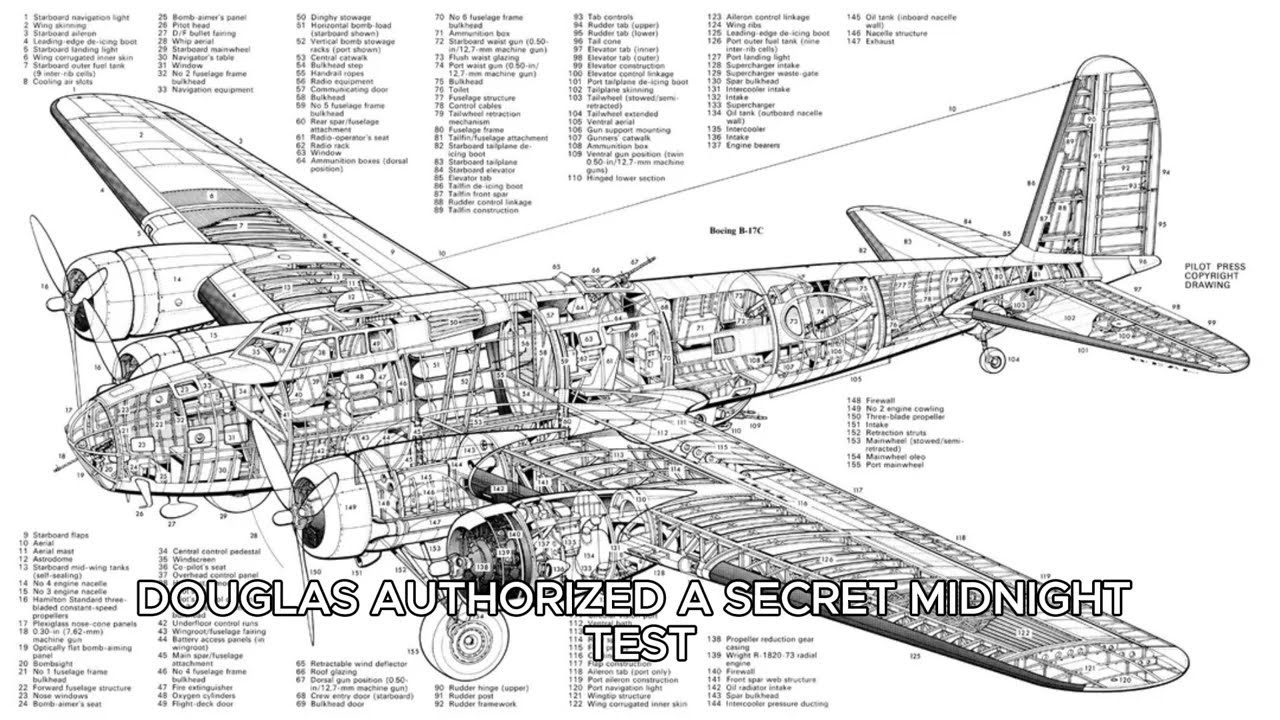

Nor was it aluminum, which flowed in from Alcoa faster than it could be used. The crisis was the bomber itself. Each B17G contained 140,000 parts, the wings alone requiring 12,000 rivets per side, connecting seven overlapping layers of aluminum skin to an internal framework designed to withstand six times the force of gravity in combat maneuvers.

A complexity that rendered traditional assembly methods ineffective and caused production to grind to a halt. Production manager Philip Johnson walked the floor each morning at 5:00 a.m. Clipboard in hand, watching workers at wing assembly station 4 struggled to install rivets, jostling for space, waiting for one another, constantly tripping over pneumatic hoses and electrical cords.

While the wings blueprint dictated a sequential pattern that forced 17 workers to crowd a single section in a chaotic ballet that required 20 hours to complete a wing, a rate far too slow to meet wartime demands, and every failed rivet or misalignment multiplied the delay. Engineers experimented endlessly, changing tool access points, specialized jigs, fixture redesigns, even altering crew sizes.

But the bottleneck was intrinsic to the aircraft’s design. The rivets had to follow the parallel row pattern laid out in the blueprints, a pattern that made structural sense on paper, but ignored the physical reality of the three-dimensional wing and the human limitations of assembly. Amid this chaos, Frank Shamansky, a 31-year-old former Chrysler assembly worker with a wife and two daughters who had relocated to Seattle, observed the process differently than others.

While most riveters focused on their immediate task, line up the gun, fire, move to the next rivet, Frank saw the cascade of delays, how row three waited for row two, row two waited for inspection on row one, and all 17 workers burned daylight in a cramped space, generating heat, expanding aluminum slightly, and exhausting themselves while introducing mistakes that had to be corrected at a costly pace.

Drawing inspiration from his old car assembly experience where Dr. panels were installed from four corners simultaneously to allow parallel work, Frank sketched a new rivet pattern directly on his time card. Clusters positioned along structural ribs where access was easiest with radiating lines connecting clusters, creating separate zones for each worker so five riveters could operate at the same time without interference, eliminating the bottleneck, reducing fatigue and distributing heat more evenly, all while keeping the aluminum sheets aligned

within tolerances. His supervisor, Bill Hendris, who had risen from sheet metal worker to floor supervisor and was willing to listen to floor workers insights, recognized the risk, but understood the potential. Theoretical perfection was no match for practical efficiency. Hendrickx brought the idea to Donald Douglas, assistant production manager, who initially dismissed it, but reconsidered after reviewing 6 weeks of assembly logs that showed every wing took 19 to 22 hours to complete.

No crew finding a way to go faster, proving that the bottleneck was structural and not managerial. Without senior approval, Douglas authorized a secret midnight test on February 21st using a wing section previously failed in quality control, assigning Frank and four experienced swing shift riveters to implement the new pattern.

Starting at 12:14 a.m., the five worked simultaneously across the wing in their color-coded zones, executing the cluster pattern that looked chaotic, but allowed uninterrupted workflow. Within 127 minutes, the wing was complete. Less than 10% of the previous assembly time, and quality inspection by Jimmy Chen revealed virtually no defects, a fraction of the normal error rate, astonishingly precise.

Yet, structural theory still suggested the wing should fail under combat stress. So, Douglas ordered a full hydraulic stress test at 4:00 a.m., simulating flight loads up to 8.4 GS. To everyone’s shock, the wing performed flawlessly, distributing forces naturally along structural ribs with the radiating rivet connections channeling loads away from weaker points, essentially creating a wing stronger than those built to the original blueprint. By 6:00 a.m.

, Douglas knew the pattern had to be implemented immediately and escalated the results to James Murray. Boeing’s vice president of operations, who recognized the implications, scaling the pattern across all 42 wing stations could increase wing production 10-fold without hiring a single additional worker, solving the bottleneck that had crippled the entire B7 program.

Against protests from engineers and legal warnings, the new rivet pattern was rolled out in late February, leading to a staggering rise in production. 47 bombers in March, 91 91 in April, 186 by June, and 362 in September, surpassing all of 1941’s annual output, directly enabling massive eighth air force missions that overwhelmed the Luftvafa, creating formations so large that German fighters were decimated by overlapping fields of defensive fire, a wall of lead that ensured American bombers ers could strike deep into Germany, crippling

industrial targets, forcing Luftwafa attrition and sustaining the strategic bombing campaign. Frank Shamansky received a modest raise, a temporary title, and returned to relative obscurity after the war, never fully realizing the global impact of his innovation. Yet his method became the blueprint for post-war aircraft production, inspiring design for manufacturability practices across Boeing, Lockheed, Douglas, and modern aerospace engineering from the B-47 to the 787 Dreamliner, where fastener patterns are now optimized for assembly

efficiency as well as structural integrity, and where the insight that workers often understand practical construction better than designers themselves has become a cornerstone. stone of modern aerospace philosophy. A legacy proving that real innovation often comes not from theoretical genius alone, but from observing, understanding, and respecting the hands-on knowledge of those who build the machines that win wars.

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load