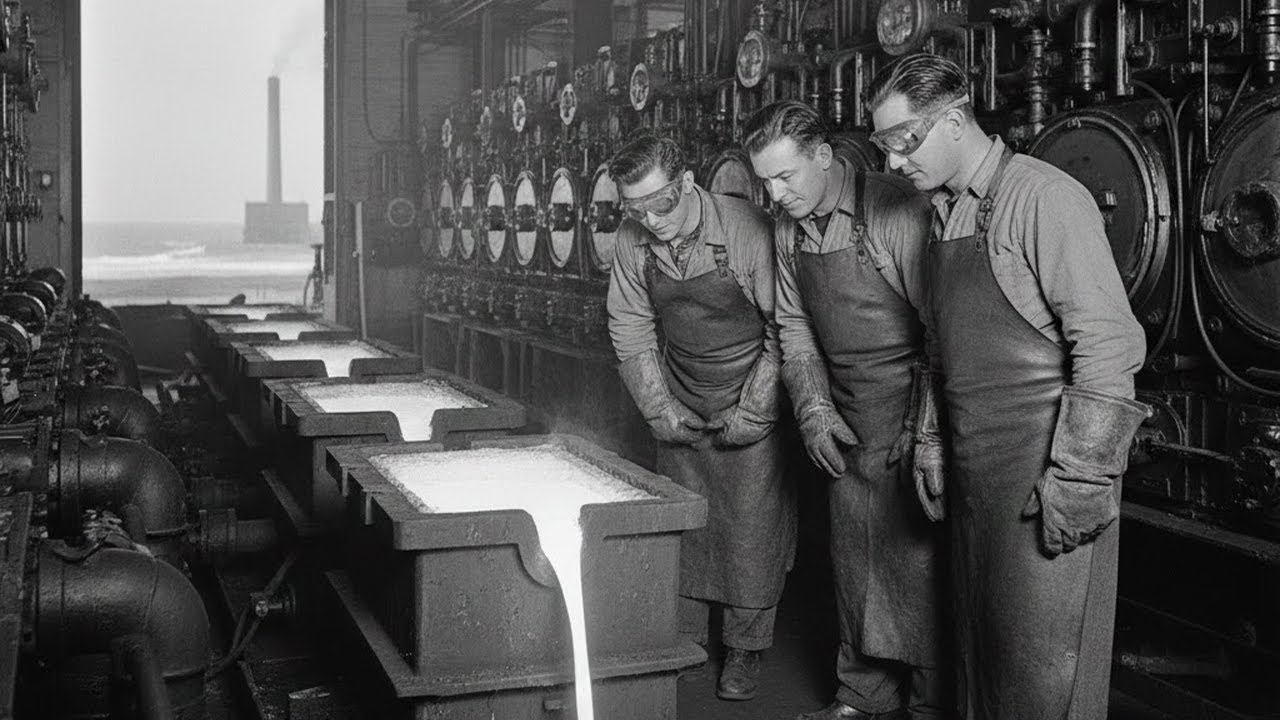

January 21, 1941, Freeport, Texas. The molten magnesium glowing white hot at 1,292° F poured from the electrolytic cell into an iron ingot mold. Workers at the brand new Dao chemical plant watched as the first ingot of magnesium extracted from seawater solidified. A silvery white metal that would become critical to American air power within months.

This was the culmination of Herbert Dao’s dream begun in 1924 to mind the ocean itself. For the first time in human history, a commercially useful metal had been extracted directly from seawater at industrial scale. The timing was extraordinary. This plant came online just 11 months before Pearl Harbor, exactly when America would need it most desperately.

Within a year, the United States would be at war and the Freeport plant would be producing 84% of America’s magnesium supply. Without this metal, lightweight, strong, and essential for aircraft construction, the Allied air campaign might have been impossible. This is the documented story of how Dao Chemical turned the Gulf of Mexico into a mine, processing 800 tons of seawater for every ton of magnesium, and in doing so helped win World War II.

Magnesium is everywhere and nowhere. As the eighth most abundant element on Earth, it comprises roughly 2% of the planet’s crust. It’s the third most plentiful element dissolved in seawater at concentrations around 1,300 parts per million. Yet, despite this abundance, magnesium doesn’t occur naturally in metallic form.

Its chemical reactivity is so strong that it exists only in compounds carbonates, chlorides, sulfates. To obtain pure magnesium metal requires chemistry and enormous amounts of energy. The metal’s initial discovery is credited to Scottish chemist Joseph Black, who performed experiments with magnesium carbonate in the 1750s. In 1808, British chemist Humphrey Davyy reported that magnesia was the oxide of a new metal.

Though he couldn’t isolate it in pure form, it took until 1828 for French scientist Antoine Busussy to obtain magnesium in its pure metallic state through chemical reduction. Commercial production of magnesium began in Germany in 1886 using electrolytic cells developed by German chemist Robert Bunson. Germany dominated world magnesium production for the next three decades, producing the metal from carnelite and other mineral deposits.

This monopoly would prove strategically significant when World War I began in 1914. During World War I in 1916, Herbert Dao, founder of the Dao Chemical Company in Midland, Michigan, received news about a new weapon being used on the Western Front. These star shells glowed eerily as they descended over enemy trenches, illuminating them for attack.

The critical component in these incendiary flares was magnesium, a metal that burned with brilliant white light. The British naval blockade of Germany had cut off all magnesium exports. Prices spiked immediately. Magnesium that had sold for050s per pound before the war jumped to $2.75 per pound virtually overnight, a 450% increase.

Herbert Dao along with half a dozen other American firms swiftly began manufacturing magnesium to fill the shortage. But Dao had a unique advantage. Beneath his chemical plant in Midland, Michigan, lay prehistoric brine deposits, the residue of ancient seas rich in magnesium chloride. Dao had already figured out how to extract bromine and chlorine from this brine through electrolysis.

But extracting and selling chemicals was one thing. Fabricating metals was something else entirely. Metals required much higher temperatures, different cell designs, and expertise DAO’s company didn’t yet possess. After a period of trial and error, Dao employees produced the first ingot of magnesium in 1916. It was only a small cake from an experimental electrolytic cell, but it proved the concept.

By 1918, DAO had sold 3,852 lbs of magnesium with nearly all going to the war effort. After the war ended, demand collapsed. Most American companies abandoned magnesium production immediately. By 1927, Dao Chemical was the only US company still manufacturing magnesium. Herbert Dao kept the operation going, convinced the metal had a future beyond military applications.

If Dao was going to stay in the magnesium business, Herbert Dao recognized he needed large volume civilian applications. Magnesium’s key property being 1/3 lighter than aluminum while maintaining good strength made it attractive for any application where weight mattered. Dao focused on automobile pistons.

In the 1920s, engine performance was limited partly by piston weight. Heavier pistons meant more inertia to overcome, reducing acceleration and fuel efficiency. Magnesium pistons, marketed as Dowo metal, offered dramatic performance improvements. The 1921 winner of the Indianapolis 500 used Dow metal pistons. Racing teams quickly adopted them.

DAO’s advertisements touted magnesium as the metal of the future, lighter than aluminum with properties that would revolutionize transportation.But the piston campaign ultimately failed commercially. While performance advantages were real, magnesium’s higher cost and tendency to corrode in certain environments limited adoption.

Automanufacturers stuck with proven aluminum technology. By the late 1920s, DAO’s magnesium operation was marginally profitable at best. The company extracted magnesium from Michigan brine deposits, but volume was limited. Herbert Dao was still searching for the breakthrough that would make magnesium economically viable. Then he had a realization.

If brine was simply the residue of ancient oceans, why not extract magnesium directly from seawater itself? The ocean was an essentially infinite resource. It was an audacious idea, extracting metal from seawater at a concentration of only 0.13% requiring processing hundreds of tons of water for each ton of metal.

Herbert Dao began planning the seawater extraction project. But on October 15th, 1930, he died suddenly at age 64. The vision would fall to his son to complete. Willard Henry Dao had been groomed from birth to lead his father’s company. Born in 1897, he spent summers during college working as a laborer at the Dowo plant, moving from department to department in coveralls, learning the business from the ground up.

When Herbert Dao died in October 1930, Willard’s transition to president was seamless. He was 33 years old and taking over a chemical company just as the Great Depression devastated the American economy. Most business leaders were retrenching, cutting costs and postponing expansion. Willard Dao did the opposite.

Like his father, he considered research, not production or sales, the key to the company’s future. Despite the depression, he approved significant expenditures for research into prochemicals, plastics, and the extraction of chemicals from seawater. The seawater project became a priority. In the mid 1930s, Dao set up a pilot plant at Curry Beach, North Carolina to perfect the process of extracting chemicals directly from the ocean.

The plant initially focused on bromine production which it sold to the Ethel Corporation for use in anti-NOC gasoline additives. The Curry Beach operation was extraordinarily successful. The pilot plant processed more than 6 cub miles of ocean water to produce nearly 2.4 billion pounds of bromine. The process worked.

Dao had proven that industrialcale chemical extraction from seawater was economically viable. But magnesium required much more energy than bromine. The metal had to be produced through high temperature electrolysis, not simple chemical precipitation. The technology needed further development and the economics remained uncertain.

Then world events intervened. War was coming to Europe and suddenly magnesium wasn’t just an interesting research project. It was becoming a strategic necessity. By the late 1930s, military aviation was transforming warfare. Aircraft were getting faster, flying higher, carrying more payload. But performance was constrained by weight.

Every pound saved in airframe structure meant more bombs, more fuel, longer range, higher speed. Magnesium alloys offered dramatic weight savings. With a density of 1.74 g per cm, about 2/3 that of aluminum, magnesium was the lightest structural metal available. Aircraft manufacturers in Germany, Britain, and the United States were increasingly incorporating magnesium components into new designs.

engine blocks, transmission housings, wheel assemblies, structural frames. Anywhere weight reduction mattered, magnesium became attractive. The metal’s properties weren’t perfect. It corroded more easily than aluminum and was more expensive to work with. But for high-performance military aircraft, the weight advantage outweighed these drawbacks.

In 1940, America’s entire magnesium production capacity was approximately 6,000 tons per year. Germany, by contrast, was producing over 30,000 tons annually from its mineral deposits. Britain was scrambling to increase production through its magnesium electron limited facility. As war spread across Europe in 1940, the strategic importance of magnesium became starkly clear.

The German Luftvafa was building bombers and fighters using magnesium components. Britain, fighting for survival, desperately needed magnesium for aircraft production and was running short. In December 1940, Britain approached the United States for help. Could American manufacturers supply magnesium? The answer was sobering. Not at the scale needed.

US production capacity was inadequate for American needs, let alone supplying Britain. The US government recognized that if America entered the war, magnesium would be as critical as steel or aluminum. A massive expansion of production capacity was essential. But where would the raw materials come from? Michigan brine deposits were already at capacity.

Mineral deposits existed, but would take years to develop. Willard Dao had the answer, the ocean. Dao Chemical needed to build the world’s largestmagnesium plant, and it needed the perfect location. The seawater extraction process required four critical inputs: seawater, freshwater, abundant energy, and a source of calcium.

In January 1940, DAO’s board of directors met at a hotel in Corpus Christi, Texas, to decide between two Gulf Coast sites, Corpus Christi and Freeport. Most board members favored Corpus Christi until a norther blew into town, bringing a massive ice storm. The board packed up and moved up the coast to Freeport where the sun was shining. On March 7th, 1940, Dao bought 800 acres bordering Freeport Harbor.

It was perfect timing and a perfect location. Freeport sits on the Gulf of Mexico at the mouth of the Brzus River, providing access to both seawater and freshwater. The region had abundant natural gas reserves for energy and the Gulf Coast was rich with oyster shells, calcium carbonate that could be calcined to produce the calcium oxide lime needed for the extraction process.

Construction began immediately. The scale was enormous. Three separate plants had to be built simultaneously. A chlorine costic plant starting December 1940. a lime plant using oyster shells early 1941 and the magnesium from seawater plant itself. The chlorine plant was critical because the DAO process required hydrochloric acid to dissolve precipitated magnesium hydroxide.

The chlorine produced during magnesium electrolysis would be recycled into hydrochloric acid through reaction with natural gas, creating a closed loop. Building the infrastructure to support thousands of construction workers and future plant employees was a challenge. Freeport in 1940 was a small town. Dao commissioned urban planners and architects to establish the new community of Lake Jackson to house workers.

In just eight months from 1940 to 1941, the company built not just a chemical complex but an entire town. The construction pace was extraordinary. The project was completed in less than a year, driven by urgency as war engulfed Europe and the likelihood of American involvement grew daily. On January 21, 1941, the first ingot of magnesium from seawater was poured at Freeport.

The plant had a designed capacity of 18,000 tons per year, triple America’s entire previous production capacity. 11 months later, on December 7th, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. America entered World War II with a functioning seawater magnesium plant already in operation. The timing was, as one historian noted, little short of genius.

The DAO seawater process was an incredible feat of engineering that took 800 tons of seawater and turned it into one ton of magnesium metal through a series of chemical steps. Step one, precipitation, making it settle. Seawater was pumped into large tanks and mixed with calcium oxide or lime, which was made from heating up oyster shells.

This lime reacted with the dissolved magnesium chloride in the seawater causing magnesium hydroxide to settle out. Magnesium chloride plus calcium hydroxide or lime becomes magnesium hydroxide plus calcium chloride. The magnesium hydroxide sank to the bottom as a thick white sludge or slurry. This step concentrated the magnesium from 0.

13% in seawater to about 2 to 3% in the sludge, a roughly 10-fold concentration. Step two, conversion to chloride, turning it back. The magnesium hydroxide sludge was filtered and then reacted with hydrochloric acid to convert it back into a concentrated magnesium chloride solution. Magnesium hydroxide plus hydrochloric acid becomes magnesium chloride plus water.

Step three, evaporation, drying it out. The magnesium chloride solution was dried out through a series of heating steps to remove all the water, leaving behind anhydrris or water-free magnesium chloride. This step was essential. Any leftover water would ruin the final step, electrolysis. The final product had to be less than 0.5% moisture.

Step four, electrolysis, splitting with electricity. The dry magnesium chloride was melted at about 700° C or 1,292° F and fed into electrolytic cells. An electric current was passed through the molten salt to break it down. Magnesium chloride becomes magnesium plus chlorine gas. The molten magnesium metal was lighter than the salt bath, so it floated to the top where it was scooped out and poured into iron molds.

The chlorine gas that was produced was captured and reacted with natural gas or methane to regenerate the hydrochloric acid needed for step two. Chlorine gas plus methane becomes hydrochloric acid plus carbon. This created a system where the chlorine was mostly recycled, making the process largely a closed loop.

Energy and working conditions. Energy use was extremely energyintensive. Extracting magnesium from seawater was extremely hot and dangerous with temperatures reaching 700° C for the electrolytic cells. workers dealt with molten metal, highly corrosive chemicals, and dangerous chlorine gas requiring constant vigilance and protective gear.

Despite the challenges,the process worked, and within months of the attack on Pearl Harbor, it was running at maximum capacity around the clock. America’s entry into World War II transformed the magnesium industry overnight. Prior to the war, total world production was approximately 32,000 tons annually. By 1942, US production alone had reached 184,000 tons, nearly 6 times pre-war global output.

DAO’s Freeport plant supplied 84% of US magnesium production in 1942. The plant operated continuously with workers on rotating shifts keeping the electrolytic cells running 24 hours a day. Production increased steadily as DAO optimized the process and expanded capacity. In December 1941, DAO won the chemical engineering achievement award from the scientific journal chemical and metallurgical engineering for its pioneering seawater extraction research.

The recognition was welld deserved. Dao had accomplished something unprecedented in industrial history. The US government recognized that even Freeport’s capacity wasn’t enough. In 1942, the government funded construction of a second seawater magnesium plant in Velasco, Texas, just a few miles from Freeport.

Built by another company, but using the DAO process, this plant added thousands of additional tons of annual capacity. The magnesium shortage was so acute that the government also funded expansion of traditional magnesium production from mineral sources in California, Nevada, and other states. But the seawater plants represented the bulk of increased wartime capacity.

Dao became the principal supplier of magnesium for US and British aircraft during World War II. The metal went into engine blocks for bombers, structural components for fighters, and countless other applications. Every B17 Flying Fortress, every B-24 Liberator, every P-51 Mustang contained magnesium components. DAO advertisements from 1941 to 1945 featured dramatic images.

pirates finding silvery treasure in the sea, magnesium ingots stacked like precious bars, warplanes soaring overhead. The copy emphasized the DAO was recovering millions of pounds of magnesium from ocean water so that warplanes can fly faster, farther. The irony wasn’t lost on observers. America was literally mining the ocean to build aircraft that would bomb Germany, the nation that had dominated magnesium production before the war.

The rapid construction and operation of the Freeport plant required thousands of workers, creating a massive housing challenge. Freeport and nearby communities couldn’t accommodate the influx. Dao commissioned the creation of Lake Jackson, a planned community built specifically to support the magnesium operation.

In just 2 months in 1940, Camp Chemical was constructed. housing, schools, shops, and infrastructure for what would become Brazoria County’s largest city. Leo A. Curtis, one of the first Michigan employees sent to Texas to help start the magnesium plant, recalled his first visit to the site that became Lake Jackson. When Dutch Bud announced where Lake Jackson was going to be, it was basically empty land.

We had to build everything from scratch and fast. Curtis became one of the first superintendent of the magnesium plant at age 24. His experience was typical. Young engineers and chemists given enormous responsibility, working long hours under intense pressure to keep production running. The work was dangerous.

In the early years, Leroy Cervanka noted they produced about a pound of sludge, waste slag, for every 10 lb of magnesium. This sludge had to be removed from the electrolytic cells while they remained at operating temperature, 1292° F. Workers used protective equipment, but accidents happened. Burns from molten metal and exposure to chlorine gas were occupational hazards.

Over time, as engineers optimized the process, they reduced sludge production to just 1/10enth of a pound per 10 lb of magnesium, a t-fold improvement in efficiency. But achieving this required constant experimentation and refinement under wartime production pressure. When World War II ended in August 1945, magnesium demand collapsed immediately.

Total US production fell from a wartime peak of 184,000 tons to just 15,700 tons in 1950, a 91% decrease. The reason was simple. Military applications drove wartime demand. Civilian markets for magnesium existed but were small. The cost of power rose in the postwar period, tightening margins and making magnesium less competitive with aluminum.

Willard Dao had anticipated this problem. In 1946, after the war ended, he established a separate magnesium department within Dao Chemical. No longer just another chemical product, but an independent business unit with its own organization and leadership. DAO invested in developing civilian markets, consumer goods, automotive parts, photo engraving technology, and surface treatment systems.

The company succeeded in maintaining production though at levels far below wartime peaks. One notable application came in 1962. The Telstar satellite, the first activecommunications satellite, used magnesium components. Dao advertised this as proof that magnesium was indeed the metal of the space age. From extracting magnesium from seawater to launching it into orbit, a poetic arc.

But economics were challenging. In the 1950s and 1960s, as global trade recovered, magnesium imports from countries with cheaper energy costs began replacing domestic production. The energyintensive DAO process became less competitive. In the 1970s, magnesium enjoyed a brief resurgence when price controls imposed by President Nixon froze the price at 35 cents per pound.

When controls were lifted, prices rose, but so did competition from Chinese producers entering the market. By the 1980s, China was producing magnesium at prices Dao couldn’t match. In 1990, Dao, which had been the world’s largest magnesium manufacturer for decades, lost that position to Chinese producers. Then came the final blow.

In September 1998, Hurricane Francis struck the Texas Gulf Coast with devastating force. The Freeport Magnesium facility sustained major damage from flooding and storm surge. Combined with already marginal economics, Dao made the decision not to rebuild. The facility was decommissioned and raised soon after, ending 57 years of continuous production.

On a site that had once housed the world’s most advanced seawater extraction plant, nothing remained but concrete foundations and memories. The Dao seawater magnesium process accomplished something remarkable. It proved that oceans could be mined for metals on an industrial scale. Prior to 1941, this was considered fantasy.

After Freeport, it was proven technology. During its operational life from 1941 to 1998, the Freeport plant and its successor facilities produced hundreds of thousands of tons of magnesium that enabled the Allied air campaign in World War II, development of the jet age and space exploration, advances in automotive engineering, and modern consumer electronics and devices.

The process influenced thinking about resource extraction. If magnesium could be extracted from seawater at 1,300 parts per million concentration, what else was possible? Researchers have since explored extracting uranium, lithium, rare earth elements, and other materials from seawater. Today, companies like Magrathia Metals are developing modern seawater magnesium extraction processes, building on the foundation DAO established.

The potential integration with desalination plants using magnesiumrich brine as feed stock offers sustainability advantages that weren’t available in the 1940s. The environmental legacy is mixed. The DAO process was relatively clean by industrial standards. Seawater was returned to the ocean after magnesium extraction.

Oyster shells provided renewable calcium and chlorine was recycled rather than released. But the energy intensity meant substantial carbon emissions from natural gas combustion. Modern calculations estimate the process produced 5 to 10 kg of CO2 equivalent per kilogram of magnesium. substantially lower than some competing processes but still significant at industrial scale.

Ironically, Dowo Chemicals success in supplying magnesium to the war effort led to anti- monopoly charges from the US government by becoming the dominant American producer. Indeed, by being virtually the only US company that maintained magnesium production between the wars, Dao faced accusations of monopolistic practices. The charges were eventually resolved, but they highlighted an uncomfortable reality.

Strategic industries sometimes require monopolistic approaches to maintain capacity during peace time. The government wanted competition, but also wanted assured supply for national defense. Dao argued that it had kept magnesium production alive when every other US company abandoned it. The seawater extraction process represented enormous capital investment and technical risk that only DAO was willing to undertake.

Without that investment made years before war began, America would have entered World War II with negligible magnesium production capacity. The government ultimately acknowledged this contribution. Though the Monopoly investigation remained a sore point in company history, Willard Dao didn’t live to see the full impact of his seawater magnesium achievement.

On March 31st, 1949, he died in an airplane crash at age 51. He was flying from Midland to Texas when the plane went down. His death marked the end of an era. For 52 years, from Herbert Dao’s founding of the company in 1897 until Willard’s death in 1949, a Dao family member had led the Dao Chemical Company.

Leadership passed to Willard’s brother-in-law, Leland Don, beginning a new chapter in company history. But Willard Dao’s legacy endured. The seawater magnesium plant he built against conventional wisdom and during the Great Depression had proved essential to Allied victory in World War II.

His willingness to invest in seemingly impractical research, extracting metal from seawater atmicroscopic concentrations had paid dividends that exceeded even Herbert Dao’s original vision. The story of Dao’s seawater magnesium extraction is ultimately about vision, timing, and industrial chemistry solving strategic problems.

Herbert Dao dreamed in 1924 of mining the ocean. His son Willard built that dream during the depression when conventional wisdom said it was economically foolish. The plant came online in January 1941, 11 months before Pearl Harbor, just in time to matter decisively. Without Freeport, America’s aircraft industry would have faced severe magnesium shortages.

The alternative, developing mineral deposits, would have taken years longer. Those years might have meant fewer bombers over Germany, fewer fighters escorting them, longer war, more casualties. The technology was elegant in its way, using nothing but oyster shells, seawater, natural gas, and electricity to produce high purity metal from essentially infinite raw materials.

Processing 800 tons of seawater for one ton of magnesium sounds absurd until you realize the ocean is constantly replenishing what you remove. Today, as researchers explore mining seawater for lithium, rare earths, and other critical materials, they’re following the path DAO pioneered. The ocean contains trillions of dollars worth of dissolved materials.

The challenge isn’t abundance, it’s economics and energy. The Freeport plant may be gone, raised after Hurricane Francis in 1998, but the knowledge it generated, the techniques, the chemistry, the process engineering endures. Modern magnesium production still uses electrolytic reduction of magnesium chloride, the same basic method DAO perfected.

In 20121, the site that once housed America’s seawater magnesium plant is part of DAO’s massive Freeport complex, now the largest integrated chemical manufacturing facility in the Western Hemisphere. The ocean that Herbert Dao dreamed of mining in 1924 still laps at the shore nearby, containing the same dissolved magnesium it always has.

The difference is that now we know it’s possible to extract it. Dao chemical proved that in 1941 when America needed it most. The ocean was mined from metal. The metal built planes. The planes helped win a war. And it all started with one chemist’s audacious idea that you could extract treasure from seawater one ton at a time.

800 tons of water per ton of metal, but possible nonetheless. Herbert Dao had it right in 1924. The ocean was a mine. It just took his son 17 years to prove

News

The Maid Begged Her to Stop—But What the Millionaire’s Fiancée Did to the Baby Left Everyone Shocked DT

The day everything shattered began like any other inside the marble silent penthouse overlooking the city, a place where money…

Kevin Costner Halts Jimmy Fallon Show With SHOCKING Announcement DT

Three words from a 12-year-old boy stopped Jimmy Fallon mid laugh. But it wasn’t what Marcus said that shattered the…

Tim Scott ATTACKS Jasmine Crockett—Her Epic Clapback Leaves Him Speechless! DT

Have you ever witnessed a moment so raw, so unexpected that the entire room seemed to freeze in shock? Well,…

Kevin Costner SHOCKS Jimmy Fallon With UNIMAGINABLE Grandson Story DT

Four words from a dying child changed everything Kevin Cosner thought he knew about love. But it wasn’t what seven-year-old…

Dolly Parton ERUPTS LIVE On The View After Heated Exchange With Joy Behar DT

Everything seemed perfectly normal on the view at first. Dolly Parton entered the studio smiling and greeting the hosts warmly,…

Anthony Geary’s Final Confession on Jimmy Fallon Left the Studio in Tears DT

Sometimes five words can change everything you thought you knew about Hollywood. The microphone slipped from Jimmy Fallon’s trembling hand,…

End of content

No more pages to load