At 6:02 on the morning of June 4th, 1942, Enson Albert Kyle Ernest sat in the cockpit of a Grumman TBF-1 Avenger on Midway Island, watching mechanics fuel a torpedo bomber that had never seen combat. 25 years old, zero combat hours, zero enemy kills. Behind him in the turret sat Seaman Firstclass J Manning, age 20.

Below in the vententral position crouched radioman thirdclass Harry Frier 17 years old. The Japanese had dispatched 108 aircraft to destroy Midway that morning supported by four carriers and the entire combined fleet. Ernest TBF was aircraft 8T1 bureau number 00380, first aircraft off the Grumman production line. The TBF1 Avenger had arrived at Pearl Harbor 6 days earlier.

Ernest and five other pilots from Torpedo Squadron 8 had flown them to Midway three days ago. The rest of VT8 was somewhere at sea aboard USS Hornet flying the obsolete TBD Devastator. Ernest Detachment had the new plane bigger, faster. Nobody knew if that would matter. Lieutenant Langden Fbring commanded the six plane detachment.

At 32, the other pilots called him Old Langden. He’d briefed them 2 days earlier. The Japanese fleet was coming. four carriers, battleships, cruisers, the entire Kido Bhai that had struck Pearl Harbor. Midway had 52 combat aircraft to stop them. Three American carriers waited somewhere north. If Midway fell, Pearl Harbor was next. At 555, a truck raced down the flight line.

Marines were shouting, “Enemy carriers bearing 320° 150 nautical miles out. Launch everything.” Ernest started his engine. The right cyclone radial roared to life. He’d never dropped a live torpedo. None of them had except Febrling. Six TBF Avengers lifted off midway at 600 hours. No fighter escort. The Marine Wildcats were already scrambling to defend the island. Ernest flew behind Feverling.

Manning test fired his turret gun. Frier checked his vententral gun and radio. They climbed to 8,000 ft and turned northwest. Nothing but water for 150 m. By 1942, torpedo bombing had become a suicide mission. You had to fly low, straight, slow. The Japanese knew this.

Their zero fighters were faster than anything America had at Coral Sea. One month earlier, American torpedo squadrons had been slaughtered. Most torpedo bomber crews didn’t survive their first attack. At 0710, Ernest saw the Japanese fleet. Four massive carriers in formation, battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and above them, black specks diving toward the six American planes. Zero fighters, too many to count.

Feebrling dove toward the carriers. The other five Avengers followed. Ernest pushed his stick forward. Manning opened fire. Frier was firing from below. Tracers were everywhere. The first TBF exploded in midair. The second tumbled into the sea, then the third. Then the fourth. Ernest saw Feebling’s plane spiral down. Five Avengers gone in less than 3 minutes.

Ernest was alone. Zeros were coming from three directions. 20 mm cannon fire punched through his windshield. Glass shrapnel hit his neck. Blood ran down inside his flight suit. His instrument panel exploded. The compass stopped working. Manning’s gun went silent. Frier came on the intercom. Manning was hit. Bad, maybe dead.

Frier himself was wounded. Ernest was 200 ft above the water. He opened his bomb bay doors and released his torpedo at the nearest cruiser and missed. More cannon fire tore through the fuselage. His elevator controls went dead. The stick wouldn’t respond. The Avenger should have crashed. Instead, it kept flying level. If you want to know whether Ernest survived the flight back to Midway, please hit that like button.

Every like helps YouTube share this story with more people. And please subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to Ernest. He was still taking fire. Bullets hitting the armor plate behind his seat. His hydraulics were shot. One landing gear wheel wouldn’t extend. No compass, no airspeed indicator, no altimeter, no radio. Manning was definitely dead. Blood everywhere in the turret.

The right engine was still running. And when he adjusted his elevator trim tabs, the aircraft responded. Not much, just enough to gain altitude and turn slightly. He was controlling a 3-tonon aircraft with trim tabs designed for fine adjustments. Ernest nursed the crippled TBF into a cloud bank. The zeros broke off.

They assumed he was finished. He flew east by dead reckoning, following the morning sun. If he missed midway, the next land was Pearl Harbor, 1,200 m away. He had maybe 2 hours of fuel, one wheel, no instruments, a dead gunner, a wounded radio men, and 73 bullet holes he didn’t know about yet. Ernest flew at 2,000 ft inside the cloud.

The TBF shuddered with every adjustment of the trim tabs. The big cyclone engine was running rough, but it was running. That was all that mattered. He had no way to check his fuel. The gauge was destroyed along with everything else on his instrument panel. He estimated he’d burned maybe half his fuel getting to the Japanese fleet and attacking.

That left him roughly 90 minutes, maybe less. 200 m back to Midway. He had to find it. The Pacific Ocean covered 64 million square miles. Midway atal was 2 square miles of coral and sand. Miss it by 5 miles and he’d never see it. He’d run out of fuel and ditch in the ocean. With one wheel down, the TBF would cartwheel and break apart on impact.

He and Frier would have maybe 30 seconds before it sank. Frier’s voice came through the intercom. He was conscious again. He’d been knocked out by the same 20 mm shell that killed Manning. Blood was running down from the turret into his position. He couldn’t tell if it was Manning’s blood or his own. He was wounded, but he could move.

He tried to see into the bomb bay through the small window to confirm the torpedo was gone, but Manning’s blood covered the glass. Ernest told Farrier to stay on the intercom. He needed to know someone else was alive. The solitude at 2,000 ft with a dead crewman behind him and instruments that looked like a junkyard was making it hard to think.

Frier acknowledged his voice was weak but steady. The trim tabs were designed to make tiny adjustments during level flight. Ernest was using them to control pitch and maintain altitude. When he adjusted the tab nose down, the aircraft descended. Nose up, it climbed. But the response was slow, sluggish. If he overcorrected, the TBF would enter a dive or climb he couldn’t recover from.

He had to think 5 seconds ahead of every adjustment. His rudder still worked. That gave him directional control. He could turn, but every turn bled off air speed and altitude. He had to keep the turns gentle. The aircraft was barely controllable in straight flight. A hard turn would probably kill him.

At 0745, he broke out of the clouds. The sun was higher now, still east. He corrected his heading slightly. Frier asked if they were going to make it. Ernest didn’t answer. He didn’t know. The flight back was taking longer than the flight out. He was flying slower, more cautious. The TBF was damaged in ways he couldn’t see. Control surfaces were probably shot up.

The airframe had taken dozens of hits. Something could fail at any moment. A fuel line could rupture. The engine could seize. The tail could fall off. He was flying a dying aircraft and hoping it would last 30 more minutes. At 0820, he saw smoke on the horizon. Black smoke. Midway was burning.

The Japanese strike had hit the island while he was attacking their carriers. He corrected his heading toward the smoke. The island came into view 10 minutes later. Sand, buildings, runway. He’d found it. Now he had to land on one wheel with no hydraulics, no flaps, no speed control. The Marines on Midway had just been bombed. They’d be trigger-happy. Ernest had no radio to announce his approach.

He had to follow the emergency procedure for damaged aircraft. A specific flight pattern with specific turns. If he didn’t execute it perfectly, the anti-aircraft guns would shoot him down half a mile from safety. And if he survived that, he still had to land a three-tonon aircraft on one wheel using only trim tabs at 120 mph.

on a runway probably cratered by Japanese bombs. Ernest circled midway at 1500 ft. The runway was intact. The Japanese had hit fuel tanks and buildings but missed the runway. He could see fires burning across the island. Smoke drifted south. He began the emergency approach pattern. Left turn, straight leg, right turn, straight leg.

The specific sequence that told ground forces he was friendly and damaged. Anti-aircraft gunners tracked him but held fire. They recognized the pattern. One of their own was coming home. Ernest completed the sequence and turned onto final approach. The runway was 6,000 ft long, plenty of distance, but he had one wheel and no flaps.

Normal landing speed for a TBF was 75 knots. Without flaps, he’d be coming in at over a 100 knots. Fast. Very fast. He adjusted the trim tabs to descend. The nose dropped slightly. The TBF began losing altitude. 300 ft. 200 100. The island was rushing toward him. He could see Marines running toward the runway. Ambulances fire trucks. They knew what was coming. 50 ft.

The right main gear was down and locked. The left gear was stuck retracted. When the right wheel touched, the aircraft would pivot left and cartwheel. Standard procedure was to land as slowly as possible and try to keep the wing up as long as possible. But Ernest didn’t have that option. He was coming in hot with almost no control, 20 ft.

He adjusted the trim tabs to level off. The TBF settled toward the runway. The right wheel touched concrete at 0944. The aircraft bounced, came down again. The right gear held. The left wing dropped. Ernest fought to keep it up using rudder and trim. The wing tip scraped the runway. Sparks flew. The propeller was still turning. If the left wing dug in, the aircraft would flip.

The TBF slew left. Ernest kept the rudder hard right. The tail swung around. The aircraft spun 90° and stopped. Engine still running. Ernest shut it down. silence. He sat in the cockpit for 3 seconds. He was alive on the ground at midway. Marines surrounded the aircraft. Medics climbed onto the wing. They pulled open the canopy. Ernest tried to stand, but his legs wouldn’t work.

They lifted him out. Blood covered his flight suit. His neck wound had bled for 90 minutes. He pointed to the turret. Manning was up there. They needed to get Manning. Two medics climbed to the turret. They looked inside and climbed back down. One of them shook his head. Ernest already knew.

He’d known since 0715 when Manning’s gun went silent. Frier was pulled from the vententral position. He was conscious, wounded, but walking. 17 years old, and he just survived what nobody should survive. Ground crews examined the TBF. They started counting bullet holes. Seven in the engine cowling, 15 in the fuselage, 20 in the wings, 30 in the tail section. They stopped counting at 73.

64 hits from 7.7 mm machine guns. Nine hits from 20 mm cannons. The elevator control cables were severed. The hydraulic lines were cut. The compass was destroyed. One propeller blade had a bullet hole through it. A photographer arrived. Bureau number 00380 needed to be documented. First TBF Avenger in combat. Only survivor of six.

Flew 200 miles with no elevator control. Landed on one wheel. The aircraft would be shipped to Pearl Harbor for examination. Engineers needed to understand how it stayed airborne. Ernest was taken to the base hospital. Doctors removed glass fragments from his neck. The wound wasn’t deep, but he’d lost blood. They cleaned it and bandaged it.

he’d be fine physically, but five pilots were dead. Jay Manning was dead. 15 more VT8 pilots had launched from Hornet that morning in TBD Devastators. None of them came back except Enson George Gay, who was picked up from the ocean the next day. Torpedo Squadron 8 had sent 21 aircraft into combat on June 4th. 48 men, three survived. Ernest Farrier Gay. 45 dead. 94% casualties.

The highest loss rate of any American squadron in any single action in the entire war. And the battle wasn’t over yet. American dive bombers were still attacking the Japanese carriers. The outcome of the entire Pacific War was being decided while Ernest sat in a hospital bed on Midway.

By noon on June 4th, the outcome of the Battle of Midway was clear. American dive bombers from Enterprise in Yorktown had caught three Japanese carriers with their decks full of armed aircraft. Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu were burning. A fourth carrier here was hit that afternoon and sank the next day. Japan had lost four fleet carriers in one day. The backbone of the Keobai was broken.

The carriers that had struck Pearl Harbor were gone. The sacrifice of torpedo squadron 8 had made it possible. The six TBFs from Midway attacked first, then 15 TBD Devastators from Hornet, then torpedo planes from Enterprise in Yorktown. All three attacks failed to score a single torpedo hit, but they pulled the Japanese fighter cover down to sea level. They forced the carriers to maneuver constantly.

They prevented the Japanese from launching their own strike. And while the Zeros were busy destroying torpedo planes at wavetop height, American dive bombers arrived at altitude unopposed. VT8 had bought that window with blood. 45 men dead, 21 aircraft destroyed, zero torpedo hits, but they changed the course of the war. Ernest remained in the hospital on midway for 2 days.

Admiral Chester Nimttz flew in from Pearl Harbor on June 5th to inspect the island and meet with survivors. He visited Ernest in the hospital. The admiral asked what happened. Ernest told him the launch, the attack, Manning killed, the flight back on trim tabs alone, the landing. Nimttz listened without interrupting. When Ernest finished, the admiral was quiet for several seconds.

Then he said Ernest’s return flight was an epic in combat aviation. The words weren’t casual praise. Nimttz had commanded submarines in World War I. He’d seen combat. He knew what was routine and what was extraordinary. Flying 200 m with no elevator control and landing on one wheel was extraordinary.

Two weeks later, the Navy announced Ernest would receive two Navy crosses for June 4th. The first for pressing home his attack against overwhelming opposition. The second for bringing his aircraft and crew back to Midway. Two Navy crosses in one day for one mission. Almost unprecedented. The citations were approved before the damaged TBF had even reached Pearl Harbor for inspection. Frier also received the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Purple Heart.

He’d been wounded but stayed conscious. He’d helped Ernest by confirming systems and providing whatever information he could from his position. 17 years old and decorated for valor, but the awards meant little compared to the losses. Lieutenant Feebrling was dead. The five other TBF pilots were dead. Their gunners and radio men were dead.

18 men total from the Midway detachment and from Hornet, Lieutenant Commander John Waldron was dead. Every pilot and crewman from his 15 TBDs was dead except George Gay. VT8 had been effectively annihilated. The squadron was reconstituted in July. New pilots, new aircraft, new crews. The rebuilt VT8 was assigned to USS Saratoga and sent to the Solomon Islands.

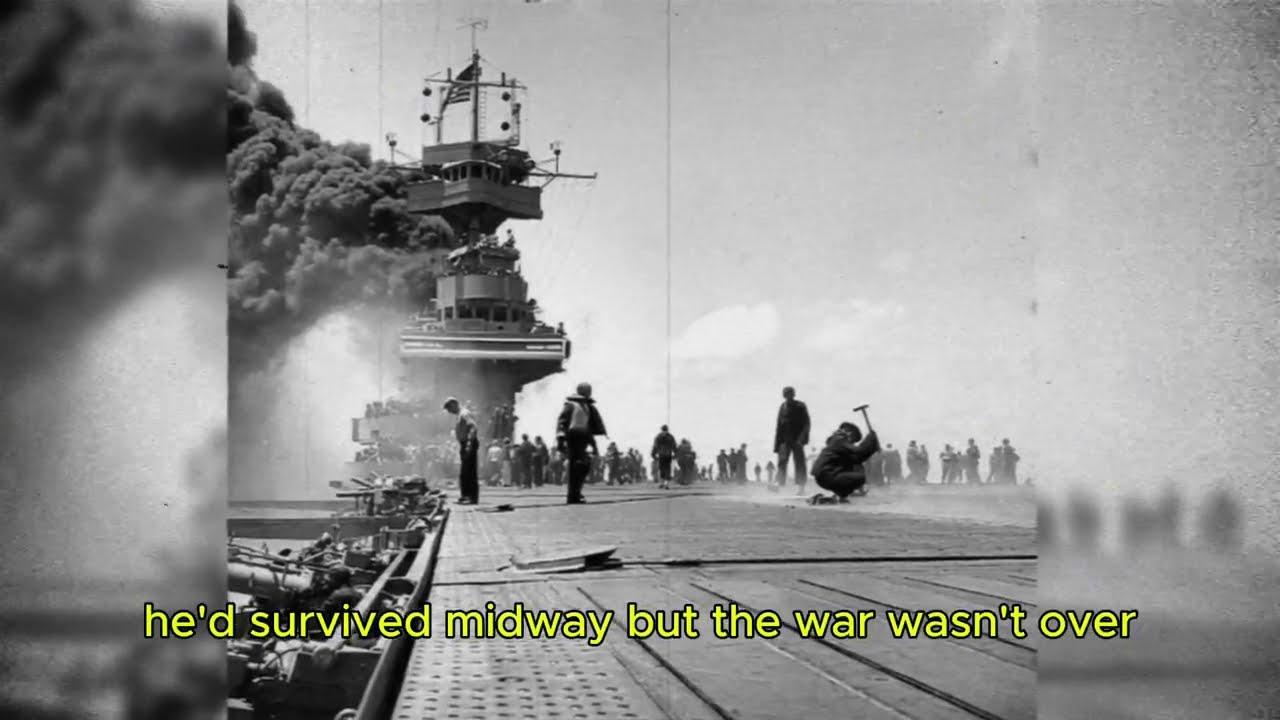

The Marines had landed on Guadal Canal in August. Japanese forces were counterattacking. The Navy needed every torpedo squadron in the Pacific. Nest went with them. He’d survived midway, but the war wasn’t over. He was 25 years old with three months of combat experience. The Navy needed experienced pilots, men who’d seen action and lived. Men who knew how to survive.

Ernest was now one of the most experienced torpedo bomber pilots in the Pacific Fleet. In September and October 1942, VT8 flew missions from Saratoga and later from Henderson Field on Guad Canal. Ernest flew strike missions against Japanese cruisers and destroyers. He bombed shore installations. He attacked transports.

The aircraft were better. The tactics were better. The Avenger was proving itself as the best torpedo bomber in the war. But the missions were still dangerous. Japanese fighters were still faster. Anti-aircraft fire was still deadly. On September 16th, Ernest was part of a strike force that put a torpedo into a Japanese cruiser.

On October 9th, he led a flight that bombed enemy positions at Cape Esperants. The missions added up. The risks added up. By November, the jungle and exhaustion had broken most of VT8. The squadron was withdrawn and disbanded for the second time. Ernest had earned a third Navy cross, three and 6 months.

But the question nobody could answer was how long his luck would hold. Ernest flew his last combat mission from Henderson Field on November 12th, 1942, 6 months after Midway. The squadron had lost more pilots and crews at Guad Canal. Not as catastrophically as June 4th, but steadily. One plane lost here. Two pilots killed there. The cumulative effect was the same.

By November, VT8 was exhausted. The survivors were rotated back to the United States. Ernest combat record was extraordinary. Three Navy crosses, multiple strike missions, zero aircraft lost under his command after Midway. He’d proven that June 4th wasn’t luck.

He was simply one of the best torpedo bomber pilots in the Navy. Calm under fire, excellent judgment, able to make decisions when everything was going wrong. Those were the qualities that kept pilots alive. The Navy recognized it. Instead of giving Ernest a desk job, they made him an instructor. New torpedo bomber pilots needed to learn from someone who’d survived, someone who could teach them what worked and what got you killed.

Ernest spent 1943 training the next generation of naval aviators. He taught them how to approach a target, how to evade fighters, how to survive when your aircraft was damaged, how to fly on instruments that weren’t there anymore. But Ernest didn’t stay an instructor forever. The Navy needed experienced combat pilots for new missions.

After the war in the Pacific ended in August 1945, Ernest remained in the Navy. He joined in 1941 expecting to serve a few years, but naval aviation was his career now. He was good at it. The Navy needed men like him. In the years after the war, Ernest flew different missions, hurricane reconnaissance, weather observation, search and rescue.

The Navy was adapting to peaceime operations, but still needed skilled pilots. Ernest flew B17s modified for hurricane hunting, flying into storms that would destroy most aircraft, reading weather patterns, saving lives by providing early warnings. It wasn’t combat, but it was dangerous work that required the same skills, situational awareness, calm decision-making, ability to handle damaged aircraft.

He was promoted steadily, lieutenant, lieutenant, commander, commander, captain. Each promotion brought more responsibility. He commanded squadrons. He commanded air stations. In the 1960s, he was given command of Naval Air Station Oceanana in Virginia, one of the largest naval air stations on the East Coast, thousands of personnel, hundreds of aircraft. The boy who’d flown a Shotup Avenger back to Midway was now responsible for an entire air station.

Ernest retired from the Navy in 1973. 31 years of service. He’d seen the Navy transform from propeller-driven torpedo bombers to supersonic jets. From 1942, when America was losing the war to 1973, when America had the most powerful navy in the world, he’d been part of that transformation.

After retirement, Ernest rarely spoke about Midway. Other veterans from the battle became famous. George Gay wrote a book and appeared on television. He was called the sole survivor of Torpedo Squadron 8. Ernest and Frier joked that they were the other sole survivors. But Ernest didn’t seek publicity. He’d done his duty. That was enough.

The Battle of Midway remained the defining moment of his life. June 4th, 1942. The day he lost friends. The day he flew an aircraft that shouldn’t have stayed airborne. the day he learned what he was capable of when everything was falling apart. Those 90 minutes from the Japanese fleet back to Midway had tested him in ways nothing else ever would. Historians later studied the battle.

They analyzed every decision, every attack, every loss. The sacrifice of Torpedo Squadron 8 was recognized as crucial to the American victory. The three torpedo attacks pulled Japanese fighters out of position. They prevented the Japanese counter-strike. They created the window for dive bombers to attack unopposed.

45 men dead, but four Japanese carriers sunk. The turning point of the Pacific War. TBF Avenger Bureau number 00380 was eventually retired from service. The aircraft that had been first off the production line and survived 73 bullet holes was displayed in museums, a reminder of what could be survived with skill and determination, a reminder of the price paid at Midway.

Harry Frier also made the Navy his career. The 17-year-old radioman who’d survived Midway continued flying combat missions through the rest of the war. He flew with VT3 and later returned to VT8 when the squadron was reconstituted again. He saw action in the Eastern Solomons and throughout the Pacific campaign.

He was commissioned as an enen in 1945 and retired as a commander in 1970. 25 years of service. Like Ernest, he rarely sought attention for what happened on June 4th. The two men stayed in contact after the war. They understood something nobody else could. what it felt like to be the only survivors. What it meant to watch five aircraft explode in 3 minutes. What it took to fly 200 m in a dying aircraft.

They didn’t need to talk about it often. They just knew. Over the decades, military historians became increasingly interested in the Battle of Midway. It was studied at the Naval War College, analyzed in staff colleges, written about in books and documentaries.

The tactical decisions, the intelligence breakthrough that revealed Japanese plans, the timing that put American carriers in position, the luck that put dive bombers over the Japanese fleet at exactly the right moment, and always the sacrifice of the torpedo squadrons. VT8 from Hornet and Midway. VT6 from Enterprise. VT3 from Yorktown. 51 torpedo bombers launched. 35 shot down. 89 men killed. Not a single torpedo hit.

But the Japanese fighters were drawn down. The carriers were forced to maneuver. The counterstrike was delayed. The dive bombers arrived unopposed. Military analysts called it the most one-sided tactical exchange in naval aviation history. 89 men killed for zero direct results. But strategically, it was decisive. Without those torpedo attacks, the dive bombers might have faced the full Japanese combat air patrol.

The battle might have ended differently. The war might have lasted years longer. Ernest understood this better than most. He’d been there. He’d seen Feebling go down. He’d seen the other four TBFs explode. He’d flown through the debris of aircraft that had been intact 30 seconds earlier.

He knew the sacrifice wasn’t wasted, but knowing didn’t make it easier. In the 1990s and 2000s, Ernest occasionally attended Midway commemorations. He met younger naval aviators. They asked questions about the battle, about the TBF, about flying on trim tabs, about landing on one wheel. He answered them matterof factly. No dramatization, no embellishment, just what happened. Some historians asked why he never wrote a book like George Gay did.

Ernest’s answer was simple. He’d done his job. That was all. Writing a book would have felt like seeking credit for something 45 other men paid for with their lives. He didn’t want that. The TBF Avenger became one of the most successful naval aircraft of World War II. Over 9,000 built, used by the Navy and Marines throughout the Pacific.

Reliable, tough, effective. The disaster at Midway was its combat debut, but not its legacy. The Avenger went on to sink dozens of Japanese ships and submarines. It proved the design was sound. The tactics just needed refinement. Bureau number 000380 became a symbol of that toughness. 73 hits and it flew home. Engineers who examined it at Pearl Harbor couldn’t fully explain how.

The elevator cables were severed. The hydraulics were destroyed. Fuel lines were punctured but sealed themselves. The right cyclone engine had taken seven hits but kept running. It should have been impossible, but impossible was a word that didn’t apply on June 4th, 1942. Impossible was staying in formation while five aircraft around you exploded.

Impossible was flying 200 m with no instruments. Impossible was landing on one wheel at 120 mph. Ernest had done all of it in 90 minutes and then spent the next 31 years serving quietly without expecting recognition. Albert Kyle Ernest died on October 27th, 2009. He was 92 years old, 67 years after Midway.

He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors, three Navy Crosses, 31 years of service, one of the last survivors of torpedo squadron 8. Harry Frier outlived him by 7 years. He died in May 2016 at age 90, also buried with honors. The last two survivors of the Midway TBF detachment were gone, but what they represented remained.

Courage under impossible circumstances. Duty when survival seemed unlikely. The willingness to fly into hell because someone ordered you to. And because your country needed you to. The story of June 4th, 1942 survived because people remembered. Veterans associations preserved records. Historians interviewed survivors.

The Navy maintained documentation. Photographs of Bureau number 00380 were archived. The bullet riddled TBF became evidence of what could be survived. Military aviation changed dramatically after World War II. Jet engines replaced propellers. Missiles replaced torpedoes. Carriers grew larger. Aircraft grew faster. But the fundamental lessons remain the same.

Training matters. Discipline matters. Courage matters. The ability to function when everything is going wrong matters most of all. Young naval aviators in the 21st century still study the Battle of Midway.

They analyze the tactical decisions, the communication failures, the coordination problems, why Hornets air groupoup flew the wrong heading, why torpedo squadrons attacked without fighter escort, why American torpedoes failed so often. The mistakes are studied so they won’t be repeated. But they also study what went right. The intelligence breakthrough that revealed Japanese plans. The positioning of American carriers.

The decision to launch strikes immediately despite incomplete information. The bravery of pilots who attacked knowing they probably wouldn’t survive. Those decisions won the battle. Ernest flight back to Midway is used as a case study in aviation survival. How he maintained control using only trim tabs. How he navigated without instruments. how he executed the emergency landing procedure perfectly despite catastrophic damage.

Flight instructors use his example to teach student pilots what’s possible when you don’t panic. The 73 bullet holes are particularly instructive. They show where a TBF Avenger could take damage and keep flying. The engine could absorb multiple hits. The wings could be riddled and maintain lift.

The tail could be shredded and still provide stability. But the elevator control cables were vulnerable. one good burst in the right place and the pilot lost pitch control. Ernest survived because he understood he could use trim tabs as backup controls. Most pilots wouldn’t have thought of that. Most wouldn’t have had the skill to execute it. Modern aircraft are more resilient.

Redundant systems, backup controls, computerass assisted flight. But they’re also more complex. More things can fail. Pilots still need the fundamental skills Ernest had. situational awareness, ability to improvise, calm decision-making under pressure. Those skills don’t change regardless of technology.

The sacrifice of Torpedo Squadron 8 is commemorated every year on June 4th. Ceremonies at Naval Air Stations, moments of silence, names read aloud. 45 men who died attacking the Japanese fleet, three who survived. The ratio tells the story better than any words. VT8 received two presidential unit citations. one for Midway, one for Guadal Canal, the only squadron to receive that honor twice in World War II.

The citations are displayed at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. Next to them are photographs of the pilots. Young men, most in their 20s, some like Frier, still teenagers. They look confident in the photos, ready. They had no idea what was coming. Museums preserve the physical evidence. Aircraft, uniforms, medals, photographs. But the real preservation happens when the story is told.

When someone explains what happened on June 4th, why six TBF Avengers attacked without fighter cover. Why five were shot down in 3 minutes. Why the Sixth flew 200 m home on trim tabs alone. Why it mattered. The story matters because it shows what human beings are capable of. Not superheroes, not movie characters, real people.

A 25-year-old pilot who’d never been in combat. A 17-year-old radio man who lied about his age to enlist. A 20-year-old gunner who died in his turret. They were ordinary people who did extraordinary things because their country needed them to.

That’s why the story survives, not because it’s about technology or tactics, but because it’s about people who faced impossible odds and refused to quit. People who watched their friends die and kept flying. People who flew damaged aircraft 200 m because going down wasn’t acceptable. People who sacrificed everything so others could live. Every generation needs to hear these stories. Not to glorify war, but to understand what previous generations endured, what they sacrificed, what they made possible.

The world we live in today exists because people like Ernest and Frier and Manning flew into hell on June 4th, 1942. Because they did their duty even when survival seemed impossible. Because they refused to fail even when failure seemed certain. The Japanese shot Albert Ernest plane 73 times. They killed his gunner. They wounded his radio man. They destroyed his instruments. They severed his control cables.

They should have killed him, but they didn’t. And the reason they didn’t tells us something important about human capability. It wasn’t the aircraft that survived. Bureau number 00380 was a machine. Metal and wires and fuel. It should have crashed into the Pacific. The right cyclone engine should have seized after taking seven hits.

The airframe should have broken apart after absorbing 66 more. The laws of physics and engineering said the TBF shouldn’t have made it back. But Ernest wasn’t bound by those laws. He found a way. When his elevator controls failed, he used trim tabs. When his instruments died, he navigated by the sun. When his hydraulics were shot, he landed on one wheel. He adapted. He improvised.

He refused to accept that survival was impossible. That’s the lesson. Not that war is glorious. Not that sacrifice is easy, but that human beings have the capacity to overcome impossible circumstances. When they refuse to quit, when they stay calm, when they think clearly despite fear and pain and chaos, when they do their duty regardless of cost. Torpedo Squadron 8 paid a terrible price on June 4th, 1942.

45 men killed, families destroyed, futures erased. Lieutenant Feebrling never saw his 33rd birthday. Jay Manning never came home to Washington. 14 other pilots from the Midway and Hornet detachments died that morning. Their sacrifice bought six minutes. Six minutes when Japanese fighters were out of position. 6 minutes that let American dive bombers attack unopposed.

6 minutes that changed the war. Was it worth it? The men who died can’t answer that question. The three who survived carried it for the rest of their lives. Ernest lived 67 years after Midway. Frier lived 74 years. They both served their country for decades. They both built families and careers.

They both died old men. But June 4th, 1942 never left them. The sound of Manning’s gun going silent. The sight of five TBFs exploding. The 90 minutes flying home wondering if they’d make it. They made it. And because they did, we know the story. We know what happened at Midway. We know the price that was paid.

We know what human beings are capable of when everything is falling apart. Modern naval aviators still study this mission. They analyze how Ernest maintained control, how he navigated without instruments, how he executed an emergency landing procedure under impossible conditions. His flight is taught at flight schools as an example of what can be survived with skill and determination.

The lessons go beyond aviation. They apply to anyone facing impossible circumstances. Stay calm. Assess your options. Use whatever tools you have left. Improvise. Adapt. Never accept that failure is inevitable. Earnest had trim tabs. Most people have something. The question is whether you can recognize it and use it when everything else has failed.

That’s why this story matters 83 years later. Not because of the technology, not because of the tactics, but because it shows what one person can do when quitting isn’t an option. When the aircraft is dying and the instruments are gone and you’re 200 m from safety, you find a way or you die trying.

Albert Ernest found a way and his story reminds us that we can too. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor, hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about pilots who save lives with trim tabs and determination.

Real people, real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer. You’re part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location.

Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching. And thank you for making sure Albert Ernest doesn’t disappear into silence.

News

Iraqi Republican Guard Was Annihilated in 23 Minutes by the M1 Abrams’ Night Vision DT

February 26th, 1991, 400 p.m. local time. The Iraqi desert. The weather is not just bad. It is apocalyptic. A…

Inside Curtiss-Wright: How 180,000 Workers Built 142,000 Engines — Powered Every P-40 vs Japan DT

At 0612 a.m. on December 8th, 1941, William Mure stood in the center of Curtis Wright’s main production floor in…

The Weapon Japan Didn’t See Coming–America’s Floating Machine Shops Revived Carriers in Record Time DT

October 15th, 1944. A Japanese submarine commander raises his periscope through the crystal waters of Uli at what he sees…

The Kingdom at a Crossroads: Travis Kelce’s Emotional Exit Sparks Retirement Fears After Mahomes Injury Disaster DT

The atmosphere inside the Kansas City Chiefs’ locker room on the evening of December 14th wasn’t just quiet; it was…

Love Against All Odds: How Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Are Prioritizing Their Relationship After a Record-Breaking and Exhausting Year DT

In the whirlwind world of global superstardom and professional athletics, few stories have captivated the public imagination quite like the…

Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Swap the Spotlight for the Shop: Inside Their Surprising New Joint Business Venture in Kansas City DT

In the world of celebrity power couples, we often expect to see them on red carpets, at high-end restaurants, or…

End of content

No more pages to load