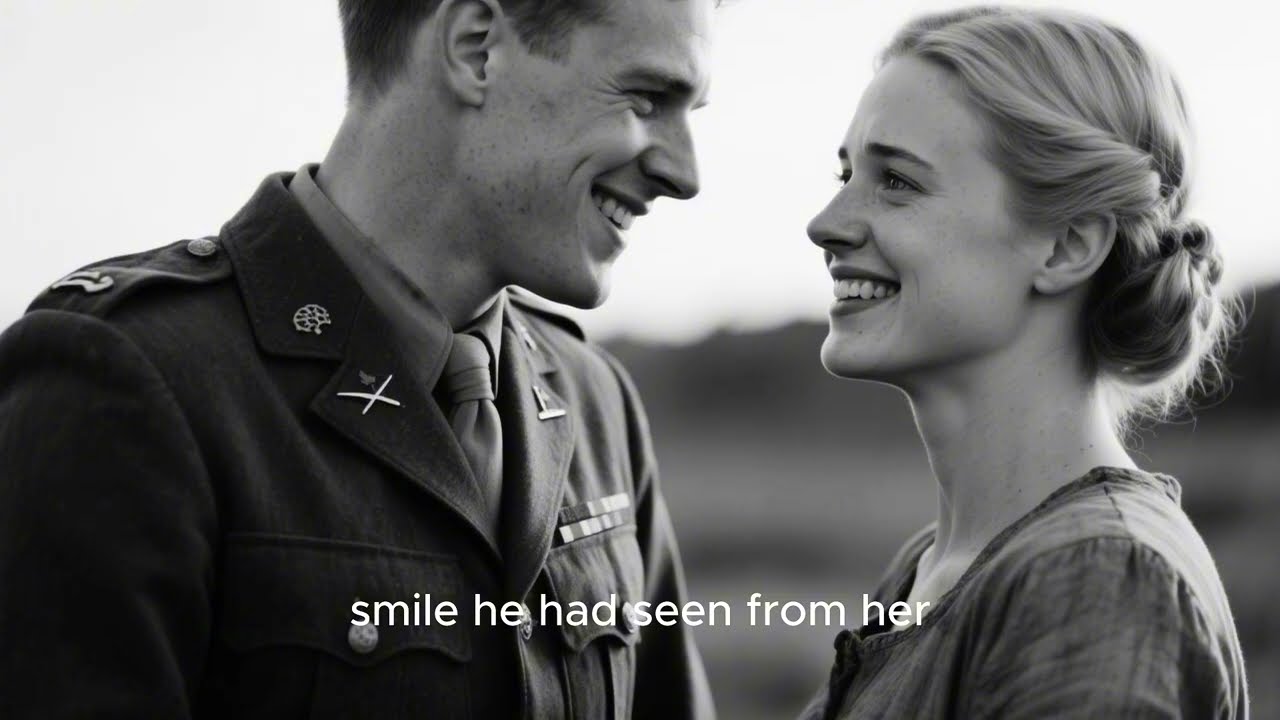

Germany, May 1945. The war was ending, but hunger had just begun. In a bombedout village near the Elba River, a young woman named Margaret Fischer knelt in the rubble of what had been her family’s bakery, searching for grain between shattered bricks. Her hands trembled, not from cold, but from weakness. She weighed 78 lb.

When the American jeep rolled into the square, dust rising behind it like a curtain, she expected nothing. Liberation meant chaos. Freedom meant starvation. But then a sergeant stepped out, looked at her for a long moment, and said three words that would change everything.

The spring of 1945 came to Germany without mercy. Fields layow, cities smoldered, and the roads filled with millions of displaced souls moving in all directions at once. Soldiers surrendering, refugees fleeing, survivors searching. In this chaos, hunger became the new enemy, more ruthless than any army. Margaret Fischer was 23 years old.

Before the war, she had been a school teacher in the small town of Toga, 40 mi northeast of Leipzig. Her father had run the town bakery for 30 years. Her mother had taught piano lessons in their parlor overlooking the Elba. Her younger brother Klouse had been conscripted in 1943 and died at Stalingrad. The family never recovered. By April 1945, Toga had become a ghost.

The bakery had been requisitioned by the Vermacht in 1944, then bombed by Allied aircraft in February 1945. Her father had died of a heart attack in the cellar during the raid. Her mother had simply stopped eating, fading away in March like a photograph left in the sun. Margaret found herself alone in a town that no longer existed, surrounded by rubble and the constant sound of artillery growing closer.

The Americans arrived on April 25th. She remembered the date because it was her mother’s birthday. The fighting was brief. The remaining German defenders, mostly old men and boys, surrendered within hours. Then came the occupation. Jeeps rolled through streets lined with broken buildings. Soldiers set up checkpoints. Military police began registering civilians.

Margaret had hidden in the bakery cellar for 3 days after the Americans came. Not from fear of violence, but from exhaustion. She had nothing left, no family, no home, no food. The cellar walls still smelled of flour and yeast, phantom scents from another lifetime. She survived on rainwater collected in a tin bucket and three potatoes she’d buried in ash.

On the fourth day, she climbed the cellar stairs. The sunlight blinded her. The square was unrecognizable. Rubble had been pushed to the sides. American trucks lined the street. Soldiers moved with purpose, setting up tents, unloading supplies. The sound of their voices, foreign and sharp, filled the air. She stood there swaying slightly. Her dress hung on her like fabric on wire.

Her hair, once thick and dark, had grown brittle. Her reflection in a broken window showed a stranger, hollowedeyed and gray. That’s when she saw him. Sergeant William James Barker of the 69th Infantry Division, Third Army, 31 years old, from a small farm outside Tulsa, Oklahoma. He had landed at Utah Beach 11 months earlier and fought his way across France, through the Ardan, across the Rine.

He had seen towns like this before, dozens of them, bombed, burned, emptied of life. But something about the woman in the square stopped him. She was kneeling in the rubble, digging with her bare hands, not frantically, but methodically, as if performing a ritual. Her movements were slow, careful. He watched her for a full minute before walking over.

“What are you looking for?” he asked in English. She looked up. Her eyes were pale blue, startling in her thin face. She didn’t understand the words, but she understood the tone. She held up a handful of dust and grain mixed together, showed it to him, then let it fall through her fingers. William understood. He had grown up on a farm during the dust bowl. He knew what hunger looked like. Real hunger.

The kind that turns people into ghosts. He reached into his jacket and pulled out a D-ration chocolate bar. Standard issue. 4 ounces of compressed chocolate, oats, and skim milk powder. Soldiers complained it tasted like dirt. He held it out to her. Margaret stared at the chocolate. She had not seen real food in weeks. Her hands remained at her sides.

This was a trick. It had to be. German propaganda had spent years telling them Americans were savages. That occupation would mean brutality and theft. Why would a soldier give her food? William stepped closer, knelt down beside her in the rubble. He unwrapped the chocolate, broke off a piece, and ate it himself. See, he said, “Safe.

” Then he held out the rest. Her hand moved without conscious thought. She took the chocolate. It felt heavy, substantial, real. She brought it to her mouth. The first taste made her eyes close. Sweetness, richness, calories. Her body awakened with desperate hunger. She forced herself to chew slowly, but her hands shook so badly she nearly dropped it. William watched her eat.

He had two more rations in his pack. He gave her both. Then he stood, said something in English she didn’t understand, and walked back to his jeep. She watched him go, still holding the rapper, not quite believing what had happened.

That evening, in the temporary mess tent, William told his friend, Corporal Daniel Reeves, about the woman in the square. Dany had grown up in Brooklyn, joined the army in 1942, survived Normandy and the Bulge. He was cynical about most things, but practical about survival. “You gave her your rations,” Dany said. “It wasn’t a question. She was starving,” William said simply. They’re all starving.

You can’t feed the whole country. I know. But William couldn’t stop thinking about her. Something in her eyes. Not just hunger, dignity. She had been someone before the war destroyed her. He could see it in the way she moved. The way she had knelt in that rubble, searching for grain like an archaeologist searching for artifacts. The next morning, he went back to the square.

She was there again in the same spot, digging in the same rubble. He brought more rations. This time she didn’t hesitate. She took them and ate while he watched. He tried to speak to her in slow English, but she only shook her head. A local interpreter eventually helped. An older German man who spoke broken English. Through him, William learned her name.

Margaret, teacher, family dead, alone. The interpreter, whose name was Hair Schmidt, explained the situation. Thousands of German civilians had no food, no shelter, no means of survival. The occupation forces provided basic rations at distribution centers, but supplies were limited and chaos reigned.

People fell through the cracks. Margaret was one of them. William made a decision that would have gotten him court marshaled if his commanding officer had known. He started bringing Margaret food everyday, not just rations. Real food from the army mess. bread, eggs, sometimes soup in a thermos. He would find her in the square, sit with her while she ate, then leave. She began to gain weight slowly.

Her cheeks filled out slightly. Color returned to her face. But more than physical recovery, something else was happening. She started to trust. By the third week of May, she was strong enough to walk more than a few blocks. William, on a rare afternoon off, showed her where the American supply depot had been set up.

He introduced her to the Red Cross workers distributing aid. He made sure she was registered for rations. He did all of this without fanfare, without expecting anything in return. One evening, after he had walked her back to the cellar where she still lived, she spoke to him in halting English.

The interpreter had been teaching her basic phrases. Why? She asked. Why you help me? William was quiet for a long moment. The sun was setting behind the ruins of the town, painting everything gold and shadow. He thought about his farm in Oklahoma, his mother’s kitchen, the way she would feed anyone who showed up at their door during the depression, hobos, drifters, neighbors who had lost everything. His father would complain about wasting food.

But his mother never stopped. Because you needed help, he said finally. It was the simplest answer, the truest answer. But for Margaret, who had spent years in a country that valued strength above compassion, that answer was revolutionary. June arrived with unexpected warmth. The occupation settled into routine. German civilians began rebuilding. American soldiers waited for orders to redeploy.

The war in Europe was over. But the war in the Pacific continued, and everyone knew what that meant. Williams unit received notice they would be shipping out to France, then possibly to the Pacific theater. He had 3 weeks left in Toga. He spent nearly every free hour with Margarette.

Their relationship was undefined. Not quite friendship, not quite romance, something deeper and stranger. She was learning English rapidly, and his German was improving. They would sit in the square, now partially cleared of rubble, and talk for hours. She told him about teaching children about her family, about the slow collapse of everything she had known.

He told her about Oklahoma, about farming wheat and cotton, about thunderstorms that rolled across the plains like freight trains. She asked him once if he had killed anyone. It was a direct question, startling in its honesty. Yes, he said. He didn’t elaborate. The weight of that yes hung between them. Are you sorry? She asked. For stopping the people who did this to you? He gestured at the ruined town.

No, for having to do it. Yes, she understood the distinction. The war had forced everyone into impossible positions. Moral clarity was a luxury neither side could afford. One afternoon in mid June, something shifted. William found Margaret at the bakery ruins.

She was sitting on what had been the front step, staring at nothing. When he approached, he saw tears on her face, not crying, just tears, as if her body was finally releasing years of held grief. He sat beside her, didn’t speak, just sat. After a long time, she said in quiet English, “I have nothing, no family, no home. When you leave, I will have nothing again. The words hit him harder than he expected.

He had been trying not to think about leaving, about what would happen to her. The occupation would continue, but individual soldiers rotated out. He would be gone, and she would be alone again in this destroyed town. He turned to her. The evening light made everything look soft, unreal. Come with me, he said. She looked at him, not understanding. When I leave, come with me to America.

It was an insane suggestion. There were regulations, laws, military protocols. Enemy nationals couldn’t just immigrate. Fraternization was officially discouraged. Marriage between occupying soldiers and German civilians was complicated, difficult, sometimes impossible. But William was serious. Completely serious. How?” she asked. “I don’t know yet, but I’ll find a way.

” Over the next week, William investigated every possible avenue. He talked to chaplain, to officers, to Red Cross officials. The answer was always the same. Possible, but difficult. There were procedures, applications, background checks. It could take months, maybe years. And most importantly, marriage was required.

He proposed to her on June 20th, 1945 in the ruins of her family’s bakery. No ring, no elaborate speech, just a simple question. Margaret, will you marry me and come to Oklahoma? She said yes before he finished the sentence. The wedding was arranged quickly through the military chaplain. Chaplain Robert Morrison, originally from Michigan, had performed dozens of such marriages.

He understood that love bloomed in strange places during war, that sometimes survival and affection became inseparable. The ceremony took place on June 27th in a small undamaged church on the outskirts of Toga. Margaret wore a dress provided by Red Cross volunteers. William wore his dress uniform.

The witnesses were Corporal Danny Reeves and Hair Schmidt, the interpreter who had facilitated their first real conversation. The chaplain spoke in English, then German, then English again. Do you, William James Barker, take this woman. Do you, Margaret Fischer, take this man? They did. They said the words. They signed the papers. After the ceremony, William took both of Margaret’s hands in his. His face was serious, intense.

You’re mine now, he said in English. Heres Schmidt translated. The phrase in German sounded different. Protective rather than possessive. Dugahurst yet. You belong to me now. Not as property but as family. As someone to be cared for, protected, brought home. Margaret understood. She was his responsibility now, and he was hers.

In a world that had fallen apart, they were building something together. The paperwork began immediately. Military bureaucracy moved with glacial slowness, but the chaplain and several sympathetic officers expedited what they could. Margaret was officially registered as the spouse of an American serviceman. She received temporary papers. A visa application was submitted. The wheels of immigration, slow and grinding, began to turn.

Williams unit received orders to ship out in early July. He would be leaving Toga, heading to France, then home. Margaret couldn’t go with him yet. Not immediately. The visa process would take months. She would have to wait in Germany alone again, but this time with papers, with status, with a future, their last night together, they sat in the square where they had first met. The summer air was warm.

Somewhere in the distance, someone was playing an accordion. Rebuilding had progressed. Some buildings had been partially repaired. Life was returning slowly, painfully, but undeniably. “I will send for you,” William said. “As soon as the papers clear. As soon as you can travel, I will send for you. I will wait,” Margarett said.

Her English had improved dramatically. She spoke in full sentences now with only a slight accent. “Promise me you’ll eat,” he said. “Promise me you’ll stay strong.” She smiled. It was the first real smile he had seen from her. I promise. He gave her everything he could before he left.

Money, addresses, contact information for Red Cross officials and military administrators who could help her. He wrote out detailed instructions in both English and German. He made sure she had food supplies, ration cards, a place to stay in a partially repaired boarding house.

The morning his unit left, he found her waiting by the convoy assembly point. She wore the same dress from their wedding. Her hair was pinned back. She looked stronger now, healthier, but her eyes were afraid. They had 90 seconds. That’s all the time his sergeant would allow. William held her face in his hands, looked at her like he was memorizing every detail.

I love you, he said. He had never said it before. The words felt enormous. She said back. I love you. Then he was in the truck. The convoy was moving. She stood on the road, one hand raised, watching him disappear into dust and distance. Summer 1945 became autumn. Autumn became winter. The war in the Pacific ended with atomic fire over Japan.

Soldiers began returning home by the millions. But Margaret remained in Germany waiting. The visa process was a nightmare of bureaucracy. Forms lost, interviews rescheduled, background checks delayed. Her status as a German national, even as the wife of an American soldier, meant scrutiny. Every detail of her life was investigated. Her father’s membership in the local business guild was questioned.

Had he supported the Nazi party? The answer was complicated. Like most Germans, he had made compromises to survive. He had paid dues, attended meetings, never enthusiastically. But compliance and enthusiasm looked the same on paper. Margarett lived in the boarding house William had arranged.

She worked for the American Occupation Administration as a translator and clerk. Her English continued to improve. She wrote to William every week. Long letters describing her days, her progress with the paperwork, her dreams of Oklahoma. His letters came back irregularly. Mail from America was slow, unpredictable. But when his letters arrived, she would read them dozens of times, memorizing every word.

He described his family’s farm, the wheat fields stretching to the horizon, the red dirt roads, his mother’s kitchen with its wood stove and gingham curtains. His father skeptical but willing to meet her. His younger sister excited to have a new sister-in-law. He sent photographs. The farmhouse white with a wraparound porch. The barn massive and red. fields of wheat under endless sky.

She kept the photographs in a tin box under her bed and would take them out at night, studying this foreign landscape that was supposed to become home. Winter in Toga was brutal. Fuel was scarce. Food remained rationed, but Margarete survived. She was stronger now. The girl who had knelt in rubble searching for grain was gone.

In her place was a woman who had learned to navigate occupation bureaucracy, who could negotiate with both American and Soviet officials, who refused to give up. The town was slowly rebuilding. Some shops reopened. Families returned. Life tentative and fragile resumed. But the Cold War was beginning. The Soviets and Americans, allies in war, were becoming adversaries in peace. Togg sitting near the Elbec dividing line. Tensions rose.

Border controls tightened. In February 1946, 9 months after William had left, Margaret received the letter she had been waiting for. Her visa was approved. She could immigrate to the United States. Travel arrangements would be made through military channels. She would travel by train to Bremer Haven, then by ship to New York, then by train to Oklahoma. She cried when she read the letter.

Not delicate tears, but deep shaking sobs of relief and terror. She was leaving. Finally leaving. But leaving meant abandoning everything that remained of her old life. The language, the culture, the landscape, even the ruins of her family’s bakery. She visited the bakery one last time the day before she left. Spring was coming early. The first flowers pushed through the rubble. She knelt where she had been kneeling the day William found her.

the day he had given her chocolate and without knowing it given her a future. She placed her hand on the broken bricks. Goodbye, Papa. Goodbye, Mama. Goodbye, Clouse. I’m going to America now. I’m going to live. March 1946. The ship crossed the Atlantic in 12 days. Margaret was sick for most of the voyage, but she didn’t care. She was moving toward something instead of away.

toward William, toward Oklahoma, toward a life that had seemed impossible a year ago. New York Harbor appeared through morning fog. The Statue of Liberty rose like a promise. Ellis Island processed her with bureaucratic efficiency. She was legal, documented. Mrs. William Barker, permanent resident, bound for Oklahoma.

The train from New York to Tulsa took 3 days. She watched America scroll past the windows. Cities, farmland, mountains, plains. Everything was big, bigger than she had imagined. The sky stretched wider than any sky in Germany. The fields went on forever. William met her at the Tulsa train station on March 15th, 1946. 10 months since they had said goodbye. He looked different, civilian clothes instead of uniform, thinner, older.

But when he saw her step off the train, his face broke into a smile that made him look 20 years old. They stood on the platform for a long moment just looking at each other, confirming the other was real. Then he crossed the space between them and pulled her into his arms. “You made it,” he whispered. “You actually made it. I promised I would wait,” she said. “I promised I would stay strong.

” The drive to the farm took an hour. Dirt roads the color of rust. fields of winter wheat just starting to green. The sky was enormous, cloudless, burning blue. Margaret had never seen so much open space. The farmhouse looked exactly like the photographs.

White clapboard, wraparound porch, flowers planted along the front, not yet blooming. William’s mother, Sarah Barker, was waiting on the porch, 60 years old, gray hair pulled back, apron dusted with flower. She looked at Margaret with a farmer’s wife’s practical assessment, then smiled. “Welcome home,” Sarah said. “Home.” The word felt foreign and perfect.

William’s father, James Barker, was more reserved. He nodded to Margaret, shook her hand, said, “Ma’am.” His skepticism was visible, but not hostile. This was a German woman, former enemy, now daughter-in-law. He would need time. William’s sister Alice, 17 years old, was fascinated. She had never met anyone from Europe.

She bombarded Margaret with questions about Germany, about the war, about everything. Margaret answered carefully, translating her trauma into words a teenager could understand. That first evening, Sarah prepared a meal. Fried chicken, mashed potatoes, green beans, cornbread. Margaret sat at the table, surrounded by William’s family, and felt overwhelmed. Not by fear, but by abundance.

There was so much food, so much space, so much safety. William reached over and took her hand under the table. “You okay?” he asked quietly. “Yes,” she said. “Yes, I am okay. But late that night, in the bedroom that would become theirs, she cried.” William held her while she sobbed, not from sadness, from release.

from the weight of everything she had survived finally lifting. The first year was hard, harder than Margaret had expected. The language was one barrier. Oklahoma English was different from the military English she had learned. The accent baffled her. Draws and colloquialisms, phrases that made no literal sense. The culture was another barrier.

Americans were loud, friendly, informal in ways that shocked her German sensibilities. Neighbors would drop by unannounced. People asked personal questions. The concept of personal space barely existed. But the hardest part was the suspicion. This was 1946. The war was over, but wounds were fresh. Americans had lost sons in Europe. Anti-German sentiment remained strong.

When people in town learned William had married a German woman, reactions ranged from curiosity to hostility. A woman at the feed store refused to serve her, called her a Nazi. Margaret stood there frozen while William’s face went hard. His mother, who had come along, stepped between them. “This is my daughter-in-law,” Sarah said quietly. “She is family.

You will treat her with respect or we will take our business elsewhere.” They left. But the incident shook Margaret. She asked William that evening if he regretted bringing her here. “Never,” he said fiercely. Not for one second, but the suspicion continued. People whispered. Some neighbors were kind, others were cold.

The local pastor visited and asked pointed questions about her faith, her politics, her past. William’s father remained distant, polite, but never warm. Margaret threw herself into becoming American. She studied English for hours every day. She learned to cook southern food. She attended church every Sunday.

Even though the services felt strange and emotional compared to the austere Lutheran traditions she had grown up with. She volunteered for community events. She tried desperately to fit in. Sarah became her ally. William’s mother had survived the depression, had fed strangers, had learned that survival required compassion. She taught Margaret how to can vegetables, how to make biscuits, how to speak with an Oklahoma accent that would hide her German origins. “Why are you helping me?” Margaret asked one afternoon while they were shelling peas on the porch.

Sarah was quiet for a moment. “Because you’re my son’s wife. Because you make him happy. Because the war is over and holding grudges won’t bring back the dead.” She paused. “And because I see how hard you’re trying.” By summer, Margaret was pregnant. The news transformed something in the family. James Barker, reserved and skeptical, suddenly became attentive.

A grandchild was coming. German or not, this was his blood. The pregnancy was difficult. Morning sickness lasted months. The Oklahoma heat was brutal, but Margaret endured. She was building a life, building a family. William worked the farm from dawn to dusk, wheat harvest, planting season, repairs.

His father was teaching him the business, slowly handing over responsibilities. At night, exhausted, he would sit with Margaret on the porch, his hand on her swelling belly, talking about the future. “What should we name him?” he asked. “How do you know it’s a hymn?” she said. “Just a feeling.” They debated names for weeks. American names, German names, compromises.

Finally, they settled on James after William’s father and Friedrich as a middle name after Margarett’s father. A bridge between two worlds. James Friedrich Barker was born in February 1947 during an ice storm. The roads were impassible. The doctor couldn’t reach the farm. Sarah delivered the baby with Margaret screaming in German and Sarah calmly giving instructions in English.

William paced in the kitchen, terrified, until he heard the baby cry. When he finally entered the bedroom, Sarah handed him his son. Small, red, perfect. William looked at Margaret, exhausted and radiant, and felt something click into place. This was his family. This was what the war had been for.

James Barker, William’s father, held his grandson and cried. It was the first time William had seen his father cry. All his skepticism, all his reservation melted. This was his grandchild. Nothing else mattered. The years unfolded like wheat growing slowly, steadily, with seasons that brought both harvest and hardship. Margarette became fluent in English.

Her accent faded to a soft lil that people found charming rather than foreign. She learned to navigate smalltown Oklahoma society, joined the church women’s group, volunteered at the school, baked pies for community fundraisers. People slowly accepted her, not all of them. Some remained cold, but enough neighbors became friends that she built a life beyond the farm.

She was no longer the German war bride. She was Mrs. Barker, William’s wife, James’s mother. Three more children followed. Elizabeth in 1949, Thomas in 1952, Sarah in 1955. The farmhouse filled with noise and life. Margarett taught her children German, but they spoke English. They were American completely. She made sure of that.

William expanded the farm, bought adjacent land, invested in new equipment. The post-war economy boomed. Wheat prices were good. The farm prospered. They added indoor plumbing, bought a television, got a telephone. The 20th century arrived in installments. But Margarette never forgot. On quiet evenings after the children were in bed, she would sit on the porch and think about Toga, about the square where she had knelt in rubble, about her parents, about her brother who died at Stalenrad, about the girl she had been starving and alone, and the man who had given her chocolate. William would find her there sometimes

lost in memory. You okay? He would ask. I am remembering, she would say. Good memories or bad? Both. In 1955, 10 years after the war ended, they received a letter from Germany. From Her Schmidt, the interpreter who had witnessed their wedding. Togg had been rebuilt. The bakery had been cleared away. New buildings stood where the ruins had been. He enclosed photographs.

Margaret looked at the images for a long time. The town looked nothing like she remembered. Everything had changed. Everyone she had known was dead or scattered. The past was truly gone. That evening, she took the photographs outside. She didn’t burn them. Instead, she placed them in the tin box where she kept William’s letters from 1945.

The ones that had sustained her through the weight, the ones that had promised her a future. William found her holding the box. “You never talk about it much,” he said. “The war? What happened to you?” “What is there to say?” she asked. “It happened. It’s over.” “But it’s not over for you.” “Not really,” she was quiet for a long time. “No,” she said finally. “It will never be over.

But I have learned to carry it. She told her children edited versions. When James asked why she had a funny accent, she said she came from Germany. When Elizabeth asked if she had been in the war, she said yes, but not in the way soldiers were. When Thomas asked if she had been scared, she said yes, always. But she never told them the full story.

Never described the hunger, the collapse, the feeling of kneeling in rubble searching for grain. The moment when an American soldier had offered her chocolate and without knowing it, offered her survival. Some stories were too heavy to pass down. 1985, 40 years after the war ended. Margaret was 63 years old. William was 71. Their children were grown. Grandchildren ran through the farmhouse.

The farm had passed to James, who ran it with the same steady competence his father had. William’s health was declining. heart problems. The doctor said he had maybe 5 years, maybe less. He was tired, the kind of tired that comes from living a full hard life.

One evening in spring, sitting on the same porch where they had spent countless evenings, William said, “We should go back.” Margaret looked at him. Back where? Germany. Toga. You should see it again. She was quiet. For 40 years, she had not returned. had not even considered it. Germany was the past. Oklahoma was home. But William’s face was serious. He was offering her something.

Closure maybe, or confirmation that leaving had been right. They flew to Berlin in June, then took a train to what was now East Germany. The Cold War had divided the country. Togg was behind the Iron Curtain. Getting there required paperwork, approval, escorts, but they managed it. The town was unrecognizable. Everything had been rebuilt in the stark, efficient style of Soviet architecture. The bakery was gone completely.

In its place stood a concrete apartment block. The square had been paved over. The church where they had married had been converted to a cultural center. Margaret walked through the town with William beside her. She felt nothing. No grief, nostalgia, just a distant recognition that this place had once mattered. They found the spot where the bakery had been. She stood there for a long time.

William held her hand. Neither spoke. An old woman approached them. She had been watching from across the street. She said something in German. Margaret responded. They talked for several minutes. The woman’s face changed. Recognition. Amazement. You are Margaret Fiser, the woman said. The teacher. I was your student. I am Greta. Greta Hoffman. Margaretta remembered.

A small girl with braids who had struggled with reading. Now an old woman with gray hair and tired eyes. What happened to you? Greta asked. I went to America. Margaret said simply. I married an American soldier. I have four children. I am a grandmother now. Greta stared at her. You survived? Yes, I survived. They talked for an hour.

Greta told her about the town, about who had died, who had stayed, who had left, about the Soviet occupation, about rebuilding, about decades of hardship and slow recovery. When they said goodbye, Greta hugged her. “You were right to leave,” she whispered. “There was nothing left here for anyone.

” That evening in a hotel room in East Berlin, Margaret sat by the window looking out at the divided city. William was asleep behind her. She thought about the past 40 years, about the girl she had been, about the woman she had become. She thought about hunger and chocolate, about rubble and wheat fields, about death and children and survival. William had saved her. That was true.

But she had also saved herself by being willing to trust, by being willing to start over, by being willing to become someone new. “You’re mine now,” he had said 40 years ago. And she was, but not in the way the words might suggest. They belong to each other. Two people who had found each other in a broken world and built something good. William Barker died in 1989 at the age of 75.

heart failure, quick and relatively painless. Margaret was with him at the end. Their children surrounded the bed. He died on the farm where he had been born, looking out at wheat fields under an Oklahoma sky. Margarette lived another 16 years. She died in 2005, age 83, in the same farmhouse. Her children and grandchildren were there. She died in spring when the wheat was just starting to green.

Her obituary in the local paper was brief. Margaret Barker, beloved wife, mother, grandmother, survived by four children, 12 grandchildren, three great grandchildren, preceded in death by husband William Barker, services at First Baptist Church, donations to the local food bank in lie of flowers. It didn’t mention that she was German. It didn’t mention the war.

It didn’t mention that she had once been starving in the rubble of a destroyed town. That an American soldier had given her chocolate. That three words, “You’re mine now,” had changed everything. But her children knew. Her grandchildren knew. And they told the story at her funeral. Not the whole story, not the darkest parts, but the essential truth. She had been lost. He had found her.

Together they had built a life. It was a small story in the vast history of the war. Millions died, millions suffered, millions were displaced. But in the midst of all that destruction, two people found each other and chose compassion over cruelty. That choice reverberated through decades, through children and grandchildren, through wheat harvests and Oklahoma thunderstorms, through an ordinary life made extraordinary by the circumstances of its beginning.

The bakery in Togo is gone. The square where Margaret Nelt is paved over. The farmhouse in Oklahoma still stands, occupied now by great grandchildren who never knew the war. But the story remains a testament to the idea that even in humanity’s darkest moments, individual acts of kindness can change everything.

William saw a starving woman and gave her food. Margarett accepted help from a former enemy. That was the beginning. Everything else followed. You’re mine now, he said. And he was right. She was his and he was hers. And together they built something worth remembering.

News

The Kingdom at a Crossroads: Travis Kelce’s Emotional Exit Sparks Retirement Fears After Mahomes Injury Disaster DT

The atmosphere inside the Kansas City Chiefs’ locker room on the evening of December 14th wasn’t just quiet; it was…

Love Against All Odds: How Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Are Prioritizing Their Relationship After a Record-Breaking and Exhausting Year DT

In the whirlwind world of global superstardom and professional athletics, few stories have captivated the public imagination quite like the…

Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Swap the Spotlight for the Shop: Inside Their Surprising New Joint Business Venture in Kansas City DT

In the world of celebrity power couples, we often expect to see them on red carpets, at high-end restaurants, or…

The Fall of a Star: How Jerry Jeudy’s “Insane” Struggles and Alleged Lack of Effort are Jeopardizing Shedeur Sanders’ Future in Cleveland DT

The city of Cleveland is no stranger to football heartbreak, but the current drama unfolding at the Browns’ facility feels…

A Season of High Stakes and Healing: The Kelce Brothers Unite for a Holiday Spectacular Amidst Chiefs’ Heartbreak and Taylor Swift’s “Unfiltered” New Chapter DT

In the high-octane world of the NFL, the line between triumph and tragedy is razor-thin, a reality the Kansas City…

The Showgirl’s Secrets: Is Taylor Swift’s “Perfect” Romance with Travis Kelce a Shield for Unresolved Heartbreak? DT

In the glittering world of pop culture, few stories have captivated the public imagination quite like the romance between Taylor…

End of content

No more pages to load