6:47 a.m.. March 12th, 1944. The morning fog outside Cassino, Italy, clung to the Liri Valley like wet cotton. Deep inside a muddy ditch. Corporal James Jimmy Dalton wasn’t looking at a map, and he certainly wasn’t consulting a rulebook. He was watching a German armored scout car grind its way toward his position at exactly 15 mph in a fair fight.

This would be a death sentence. The 222 was the Wehrmacht’s predator of choice. Four wheel drive fast enough to outrun artillery and armed with a 20 millimeter autocannon that could turn a foxhole into a grave in seconds. American doctrine was very clear on how to handle this threat.

The official field manual designated 16 approved methods for disabling light armor. You used anti-tank rifles, you used mines, or you used bazookas. But on this particular morning, Jimmy Dalton didn’t have any of those. The 34th Infantry Division was grinding through a logistical nightmare. The mines were reserved for the rear guard.

The anti-tank rifles had been phased out months ago, and the bazookas due to mud choked supply lines in the mountains. Dalton’s battalion had exactly zero functional tubes, so the Paper Tiger, the official doctrine written by engineers in warm offices back in Washington, said Dalton was helpless. It said he should stay hidden and pray the Germans didn’t spot him.

But the cast iron reality of the Italian front was different. Dalton held the only weapon he had left a length of rusted barbed wire wrapped tightly around a standard issue entrenching shovel. It looked like garbage to the officers at Battalion Command. It looked like insubordination.

In fact, Dalton had been threatened with a court martial twice for even experimenting with it. They called it an unauthorized field modification that endangered personnel. They told him to trust the supply chain. But trust is a hard thing to maintain. When you’ve watched 11 of your friends die in three weeks. Private Kowalski, Sergeant Brennan, Corporal Vargas, all dead because the approved methods required equipment that simply didn’t exist. Dalton wasn’t thinking about the court martial.

He was thinking about the physics he learned working the rail yards in Gary, Indiana. He knew that a machine is only as strong as its weakest moving part. And as that German engine whined closer, the commander standing in the open hatch, scanning the tree line. Dalton tightened his grip on the wire. He was about to bet his life and the lives of his entire company on a piece of rusted scrap metal.

The manual said it was impossible. The officers said it was illegal. But in the next 90s, a 19 year old switchman was about to prove that when the supply chain fails, American ingenuity takes over. The wire trembled in his hands. The scout car was 50 yards away. The theory was over. The experiment was about to begin.

To understand why a 19 year old corporal was risking a court martial in a muddy ditch. You first have to understand the specific hell of the Italian campaign. By September 1943. The 34th Infantry Division wasn’t marching. It was grinding. They moved up the peninsula like a millstone, fighting for every village, every river crossing and every rocky ridge. But the terrain wasn’t just difficult.

It was deceptive. In the open fields of France, American firepower could dominate. But in the tight, winding mountain roads of Italy, heavy armor like the German Tigers and Panthers struggled to maneuver. They were too wide, too heavy and too prone to mechanical failure on the steep grades. So the Wehrmacht adapted. They didn’t send monsters. They sent ghosts.

The German solution was the Sd.Kfz. 222, a vehicle that became the nightmare of the infantry. It was a masterpiece of light engineering, powered by a reliable Horch V-8 engine. It was armed with a 20 millimeter autocannon and an MG 34 machine gun. But its greatest weapon wasn’t its firepower, it was its agility.

These scout cars were fast enough to escape trouble, armored enough to shrug off rifle fire, and light enough to navigate the goat paths that bogged down the Shermans. They appeared at dawn and dusk. The gray ghosts of the Liri Valley. Now, American doctrine treated these vehicles as a minor nuisance. The manual viewed them as reconnaissance assets that should be easily dispatched.

But the manual had been written by men who weren’t ducking 20 millimeter shells. In reality, the 222s were lethally effective. They would emerge from the fog rake, an American position with cannon fire to pin everyone down, and then vanish before anyone could return fire. But the real damage came later. The scout car’s job wasn’t just to kill.

It was to map. They would spot the American foxholes, radio the coordinates back to the heavy batteries, and 12 hours later, precision artillery would rain down on those exact spots. If you saw a 222 in the morning, you were likely dead by evening. The frustration among the rank and file was absolute because they knew exactly how they were supposed to kill them.

The field manual listed the tools for the job. Anti-Tank rifles. Bazookas or defensive mines. On paper, the 34th Division was a fully equipped modern force. In reality, they were fighting a poor man’s war. The logistics were in shambles. The old anti-tank rifles had been phased out as obsolete. Yet the replacements hadn’t arrived.

Mines were strictly rationed for major defensive lines, not for daily patrols or forward operating bases. So when the scout cars came, the Americans had no answer. They were forced to fight armor with rifles and courage. And the result was a slaughter. The cost wasn’t abstract. It had names and faces that Jimmy Dalton knew by heart.

It started with Private First Class Eddie Kowalski on February 18th. Kowalski was a machinist’s son from Pittsburgh, a kid who understood steel just like Dalton. When a 222 rolled past his foxhole at dawn, Kowalski did what he was trained to do. He fired his M1 Garand at the vision slits. It was a brave act and entirely futile. The .

30-06 rounds simply sparked off the sloped German armor. The scout car’s turret rotated. The MG 34 answered, and Kowalski took three rounds to the chest. He was 20 years old. Five days later, it was Sergeant Mike Brennan. Brennan was the squad leader who had taught Dalton how to keep his feet dry in the Italian mud. He was 24, from Brooklyn with four sisters waiting for him back home when another dawn patrol rolled through. Brennan tried to close the gap. He broke cover to throw a grenade from 30 yards.

He missed the autocannon, didn’t. His mother received the telegram on March 2nd. Then came Corporal Luis Vargas on March 4th. Vargas was the heart of the squad. A kid from El Paso who spoke better Spanish than English and always shared his cigarettes. Even when he was down to his last three, by March, the German crews were getting bolder.

The scout car that killed Vargas didn’t even use cover. It drove right through the company position at dusk, machine guns blazing. Vargas made a run for cover, but the 20 millimeter shell caught him. The medic couldn’t stop the bleeding. In just six weeks, the division lost 47 men specifically to reconnaissance vehicles.

These weren’t casualties from a major offensive. They were men picked off day after day by an enemy they couldn’t touch. The anger in the ranks began to curdle into something dangerous. It wasn’t just fear of the Germans. It was resentment toward their own command. The official response from battalion headquarters was almost insulting, and its detachment.

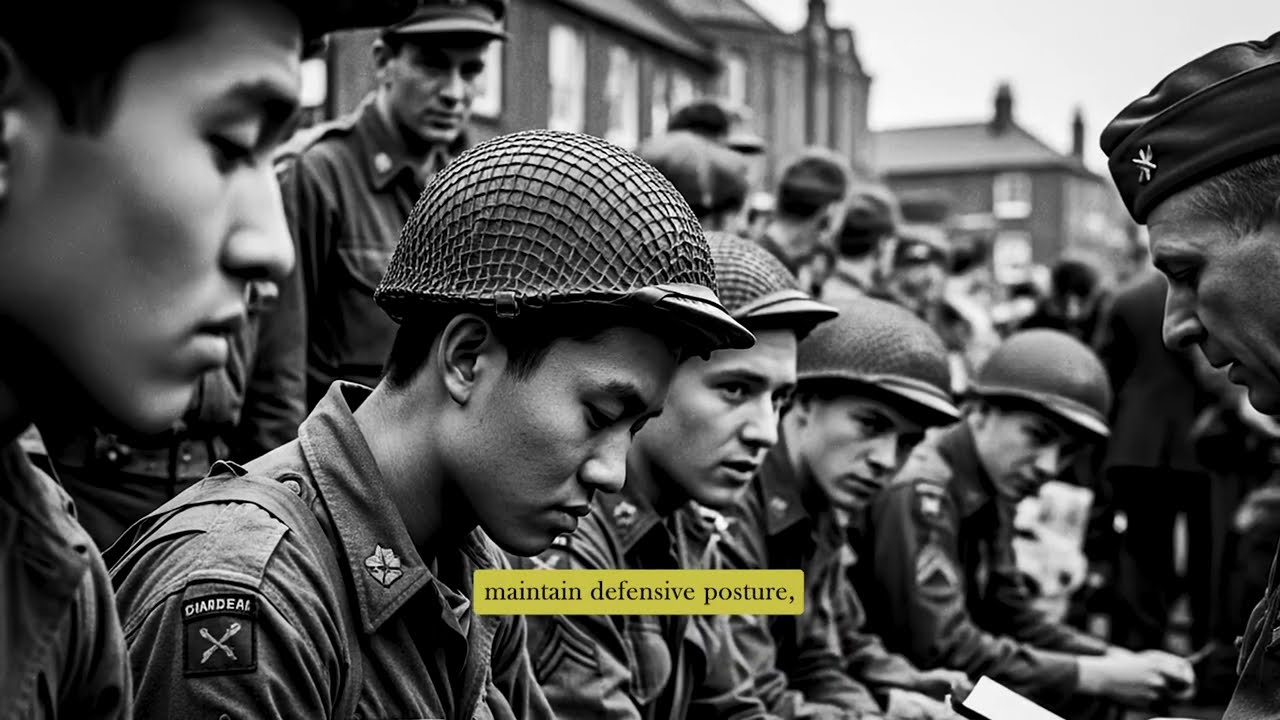

The orders were constant maintain defensive posture, conserve anti-tank assets, await resupply, await resupply. That phrase became a bitter joke in the foxholes. The breaking point for Dalton came during a briefing with Captain Reed after Vargas died. 20 exhausted, muddy soldiers gathered in a barn that smelled of gunpowder and wet wool.

Reed stood before them, and the first thing everyone noticed was his uniform. It was clean. He had just arrived from division headquarters that morning, and the contrast between his pressed fatigues and the filth covered soldiers was stark. Higher command is aware of the reconnaissance problem, Reed told them, his voice calm. Bureaucratic new bazooka shipments are expected within the month.

Until then, maintain discipline and follow engagement protocols. Dalton stood in the back, listening to the promise of next month. He knew next month might as well be next year. He looked around at the faces of the men left. Private Chen, a radio operator from San Francisco. Private Harrison, a farm boy from Oklahoma. They were terrified.

They knew that if a 222 appeared tomorrow, the engagement protocol said they should die. Like Kowalski and Brennan. It was a collision of two worlds. The officers lived in the world of logistics tables and future shipments. The enlisted men lived in the world of immediate ballistics. The cast iron reality was that no help was coming.

If they wanted to survive the next patrol, they couldn’t wait for Washington to send the right tool. They had to invent it. And Jimmy Dalton, standing in that barn, realized that the U.S. Army couldn’t save them. But maybe a switchman from Gary, Indiana, could. He didn’t have a bazooka, but he had a memory of the rail yards. He had a coil of wire, and he had an idea that was about to get him in a lot of trouble.

To understand the weapon Dalton was about to build. You have to realize that his education didn’t happen at West Point or Fort Benning. It happened in the rail yards of Gary, Indiana. Jimmy Dalton was the middle child of six raised in the shadow of the U.S. Steel blast furnaces.

His father worked 15 hour shifts handling molten iron, bringing home a paycheck that barely covered the rent. It was a hard life, the kind that forces you to grow up fast. While other kids were finishing high school. Jimmy was spending his afternoons down at the tracks. By 17, he was apprenticing as a switchman. Now, for those who haven’t worked the rails, being a switchman in the 1940s was dangerous work. It was a master class in physics and heavy machinery.

But more importantly, it taught you to think in systems. You stopped seeing a train as a single vehicle, and started seeing it as a collection of moving parts, couplers, cables, pins, and wheels. Dalton learned quickly that catastrophic failure often started with the smallest component. A loose coupler pin could derail six loaded cars.

A frayed cable could snap and cut a brakeman in half. You learn to spot the disaster before it happen, but the most valuable lesson U.S. steel taught him was cynicism. Just like the 34th Infantry Division, the rail company wasn’t interested in buying new equipment. If a coupling broke, you didn’t wait for a new one. You fixed it with whatever scrap metal, rope or wire you could find.

You improvised. You rigged temporary fixes that became permanent solutions because the alternative was stopping the line and stopping the line got you fired. So when Dalton looked at the Sd.Kfz. 222, he didn’t see an invincible war machine. He saw a mechanical system with a flaw, while the rest of the platoon was terrified of the 20 millimeter cannon.

Dalton was studying the wheels. He noticed that despite all their armor and firepower, these scout cars were bound by the laws of physics. They were top heavy. They moved fast and critically. They were predictable. The German drivers, confident in their speed, always use the same dirt roads to probe the American lines. They relied on momentum to keep them safe.

Dalton’s blue collar ballistics theory was simple math from the rail yard. If you can’t blow it up, trip it up. He realized that if you could arrest the forward motion of the front axle while the rest of the vehicle was moving at 15mph, physics would take over. The momentum would have nowhere to go but up. He sat on this idea for weeks.

He played the angles in his head, but in the Army, having an idea and getting permission to use it are two very different things. The collision between Dalton’s ingenuity and army bureaucracy happened in that barn with Captain Reed after the briefing, while the other men were filing out to clean their rifles. Dalton stayed behind.

Sir Dalton asked, what if we rigged wire across the roads? Low, taut enough to catch the axles? Captain Reed looked at him like he had just suggested, fighting the Germans with spitballs. Reed was a good officer, but he was a by the book officer. And the book the field Manual was very specific about wire. Corporal Reed sighed.

The field manual is very clear. Wire entanglements are defensive measures. They require specific positioning engineering support, and depth. They are not booby traps. Dalton pressed him. But, sir, if we just. The answer is no. Reed cut him off. We are not setting random tripwires that could injure our own men or vehicles.

It’s unauthorized, it’s dangerous, and it violates doctrine. Dismissed. It was a hard no. In the military, that’s supposed to be the end of it. You salute. You turn around and you follow orders. But Dalton walked out of that barn into the cold Italian mud, and he couldn’t let it go. The rail yard instinct was screaming at him.

He saw a loose coupler, the gap in their defenses, and he knew how to fix it. The captain saw a regulation. The corporal saw a solution. Over the next 48 hours, the cost of following the rules became unbearable. Another scout car rolled through at 4 p.m., killing Privates Chen and Harrison. Harrison.

The farm boy who just wanted to go back to Oklahoma, was cut down because a vehicle drove down a road nobody could block. That was the turning point. Dalton sat in his foxhole and did the calculation. It was simple math. If he did nothing, more men would die. If he tried his rusted shovel idea, he risked a court martial. In the logic of the yard. You don’t ask permission to save the train. You just throw the switch.

On the night of March 11th, 1944. Dalton made his choice. He decided that saving his friends was worth the risk of a military prison. He stopped being a soldier following orders, and went back to being a switchman. Fixing a broken system. He didn’t tell his squad. He didn’t tell his sergeant.

He waited until midnight, grabbed a coil of barbed wire and two shovels and crawled out into no man’s land alone. He was going to build his trap, and he was going to do it exactly the way he learned back home with scrap metal, grit and zero authorization. On the night of March 11th, 1944. The Rapido River Valley was freezing. The mud in this part of Italy didn’t just coat you. It consumed you.

It was a thick, sucking clay that made every movement a struggle. At midnight, while the rest of the company tried to sleep through the distant rumble of artillery, Corporal Dalton moved out. He carried no rifle. He carried no grenades. His loadout for this unauthorized patrol was painfully simple. A heavy coil of rusted barbed wire scavenged from a supply dump, and two standard issue M 1943 entrenching tools.

For those of you who never had the pleasure of using one, the M 1943 was a folding shovel intended for digging latrines and foxholes. It was a stamped steel tool, barely two feet long when extended. It was never designed to stop a four ton armored vehicle, but Dalton wasn’t using it as a weapon. He was using it as an anchor.

He moved 400 yards into no man’s land. This was the gray zone. The strip of territory that belonged to the Americans by day and the Germans by night. If a patrol caught him here, he was dead. If an American sentry saw him coming back, he might get shot by his own side. But the risk was calculated. Dalton had been watching the road. He found his spot where the dirt track narrowed between two ancient oak trees.

It was a natural choke point. The trees provided a canopy that shadowed the road, even in moonlight. But more importantly, they forced vehicles to stay centered. Dalton knelt in the mud and went to work. The engineering challenge here was immense. He had to create a barrier strong enough to absorb the kinetic energy of a moving vehicle.

But he couldn’t use concrete or steel posts. He had to use the earth itself. He started on the left side of the road. He unfolded the first shovel and locked the blade into place. He didn’t just drive it straight down. If he had done that, the force of the impact would have ripped it out of the ground like a loose tooth. Instead, Dalton applied the geometry of a deadman anchor.

He drove the blade into the mud at a sharp 45 degree angle, pointing back toward the American lines. This way, when the wire pulled tight, it wouldn’t pull the shovel up. It would pull it deeper into the earth. The soil resistance would multiply the holding power. The blade sank six inches. It wasn’t enough. The ground was rocky, fighting him every inch.

Dalton found a heavy rock and used it as a hammer. Clang, clang! He had to time the strikes with the distant thunder of artillery to mask the noise. He drove it down until the handle was flush with the mud. 12in of steel buried in the clay. He paced off the width of the road 18ft. He repeated the process on the right side.

Same angle, same depth. Now came the wire. This wasn’t modern smooth wire. This was 1940s. Military grade. Barbed wire, heavy, rusted and vicious. Handling it in the dark with numb hands was a recipe for disaster. But Dalton didn’t wear gloves. He needed to feel the tension. He wrapped the wire around the first shovel handle. Three full loops.

He twisted the end back onto the main line, creating a knot that would tighten under pressure rather than slip the barbs bit into his palms. He could feel the warmth of his own blood mixing with the freezing mud. But he didn’t stop. He crawled across the road, unspooling the coil. This is where the genius of the switchman came into play.

A regular soldier might have strung the wire at ankle high to trip a man or waist height to decapitate a motorcycle rider. Dalton set his wire at exactly 14in. This number wasn’t a guess. It was data. Two weeks earlier, during a daytime patrol, Dalton had examined the wreckage of a destroyed Sd.Kfz. 222, while others were looking for souvenirs. Dalton had taken out a tape measure.

He measured the distance from the ground to the center of the front axle. The 222’s suspension geometry was unique. It had double wishbone suspension with a ground clearance that varied depending on the load, but the axle itself. The solid steel bar that transferred power to the wheels sat between 13 and 15in off the deck.

If the wire was too low, the tires would simply roll over it. If it was too high, it would bounce off the sloped armor of the hull, but at 14in, at 14in, the wire was invisible to a driver looking through a vision slit. It would pass harmlessly under the front bumper, and then it would slam directly into the exposed axle shaft.

Dalton wrapped the second end around the right hand shovel. He pulled it taut. The tension had to be perfect. This was the tuning phase. If the wire was too loose, it would act like a rubber band, stretching and then snapping without stopping the car. If it was too tight.

The initial shock would shear the shovel handles before the energy could transfer to the vehicle. He pulled until the wire hummed. He plucked it like a guitar string. It sang in the cold air. A low metallic note. It was a terrifying sound because it meant the trap was live. The entire setup took 23 minutes. Dalton sat back in the ditch, his chest heaving. He checked his watch. 12:45 a.m.

the hard part was done, but the smart part was just beginning. A wire stretched across a road is easy to see if the sun hits it right, and two shovels sticking out of the ground looks suspicious to any veteran driver. So Dalton camouflaged his work. He took handfuls of the wet slurry from the ditch and carefully coated the wire.

He didn’t cake it on. That would make it heavy and cause it to sag. He applied just a thin veneer of mud to dull the shine of the metal in the gray light of dawn. The wire would vanish into the background color of the road. As for the shovels, he didn’t hide them completely. He left them partially exposed, caked in rust and dirt.

This was a psychological trick. The battlefield was littered with trash, discarded ration tins, broken crates, lost tools, a driver’s eyes trained to look for mines which are hidden, or anti-tank guns which are camouflaged. They don’t look for garbage. To a German commander scanning the road. Those shovel handles would look like just another piece of junk left behind by a retreating army.

They wouldn’t look like the anchor points of a weapon. Dalton did one final check, the height 14in the anchors angled and buried, the wire invisible. He crawled back toward the American lines at 1:15 a.m.. He had violated direct orders. He had misappropriated government property.

He had endangered his position by moving alone in no man’s land. Technically, he was 14in away from a court martial, but as he slid back into his foxhole and wiped the blood from his hands, Jimmy Dalton knew something the officers didn’t. He knew the trap was perfect. The system was rigged.

Now all he had to do was wait for the train to arrive. Dawn broke over the Liri valley with a silence that felt heavy. At 6:43 a.m. on March 12th, the fog was still thick enough to cut with a knife. Jimmy Dalton was sitting in his foxhole, eating cold rations from a tin, trying to keep his hands from shaking. He wasn’t shaking from the cold anymore.

He was shaking from the adrenaline of the gamble. The wire was out there, buried, hidden, waiting. Then he heard it. It started as a low vibrato in the ground before it became a sound in the air. The distinctive grinding whine of a German Horch V-8 engine. It was an Sd.Kfz. 222, and it was coming from the north.

Dalton didn’t move. He didn’t call out contact to the rest of the line. If he alerted them now, someone might fire a premature shot and spook the driver. The trap required the enemy to be comfortable. It required them to be arrogant. The gray shape emerged from the mist at 600 yards.

Through his own binoculars, Dalton watched the crew. They were relaxed. The commander was standing tall in the open hatch, scanning the tree line with his field glasses. The gunner was traversing the 20 millimeter cannon back and forth lazily, probably more out of boredom than tactical necessity. They were moving at 15mph, a moderate, confident patrol speed.

They had no idea they were driving toward a physics equation. The Dalton had solved the night before. At 400 yards, the car stayed dead center on the road. The oak trees were doing their job, funneling the vehicle exactly where Dalton wanted it. They were moving at 15mph. But as they approached the gap between the oak trees, Dalton’s kill zone, the driver did exactly what Dalton hoped he would do. He saw the open stretch of road and accelerated to minimize his exposure.

The engine roared. The tires spun. The vehicle surged to 30mph. Dalton put down his ration tin and picked up his rifle. He watched the front wheels. They were caked in mud, spinning a blur of gray and brown. 50 yards. 20 yards. Ten. At 6:47 a.m., the front right tire crossed the invisible line. The 14 inch height was perfect. The wire didn’t bounce off the tire.

It slipped under the fender and caught the solid steel of the axle in the fraction of a second that followed. The law of conservation of momentum took over. To understand the violence of what happened next, you have to look at the numbers. A four ton vehicle moving at 15mph possesses massive kinetic energy. That energy pushes forward.

But the wire anchored by those buried shovels, provided an absolute immovable stop. The wire pulled taut. The shovels were ripped through the earth, dragging 20ft, plowing deep furrows in the clay. But. And this is the miracle of the dead man. Anchor. They didn’t pull out. They dug in. The right side of the axle, stopped dead.

But the rest of the car, four tons of armor traveling at 44ft per second, kept going. The locked wheel became a pivot point. The car didn’t crash. It vaulted. It happened in terrifying slow motion for Dalton. First, the nose dipped violently, driving the front grille into the mud. Then the rear of the vehicle lifted.

The commander, who had been scanning the horizon a second ago, had no time to react. As the vehicle went vertical, he was thrown clear, catapulted from the hatch like a ragdoll. The car rolled once, then twice, then a third time. It tumbled down the road in a chaotic shower of mud, torn metal and gear. It came to rest upside down, 40 yards past the wire, its wheels spinning uselessly in the air.

Dalton didn’t wait to admire his work. He was already moving. Contact. Contact. Front. He screamed, not because he needed help fighting, but because he needed witnesses to the accident. Soldiers poured out of their foxholes, rifles up, expecting a firefight. What they found was a wreck. The scene was surreal.

The scout car’s engine was still running upside down, smoke pouring from the crushed engine compartment. The commander was dead. His neck broken by the fall. The gunner was trapped under the turret, unconscious, but the driver was alive. He was crawling out through the shattered windscreen, dazed, bleeding from a scalp wound.

He was a kid, maybe 22 years old, with blond hair, matted with oil and blood. He looked up at Dalton, eyes wide with shock, and raised his hands. There was no fight left in him. He had been driving down a clear road one second and tumbling through the air. He couldn’t process it. Dalton pulled him clear and shoved him toward Private Morrison. Watch him. Then Dalton did the most important thing of the morning.

While the rest of the squad was gaping at the burning vehicle. Dalton ran back to the impact site. He found the wire. It was still wrapped around the axle, stretched tight as a piano wire. The shovels had been dragged out of their holes, lying exposed in the mud like guilty evidence. Dalton worked feverishly. He unwrapped the wire from the axle, his hands burning from the heat of the metal.

He coiled it up, grabbed the shovels, and shoved the entire mess into his pack. He kicked dirt over the furrows in the road. By the time the officers arrived, the weapon was gone. Captain Reed, the clean officer from the briefing, showed up six minutes later. He walked around the overturned 222 his boots, squelching in the mud.

He looked at the dead commander. He looked at the prisoner, and then he looked at the vehicle itself. He was confused. He was looking for the blackened crater of a landmine. He was looking for the scorch marks of a bazooka. Impact. He found neither.

What happened here, corporal? Reed asked, poking the spinning wheel with his baton. Dalton stood at attention, his face a mask of innocent exhaustion. It flipped, sir. Must have hit a rut in the road at speed. Driver lost control. Reed narrowed his eyes. He walked back up the road, retracing the vehicle’s path. He saw the disturbed earth where the shovels had dragged, but without the wire, it just looked like churned up mud.

Corporal Reed said slowly. Sd.Kfz. 222s are stable platforms. They don’t just flip on flat roads. Yes, sir, Dalton replied. War is strange, sir. Reed stared at him. He knew he had to know. You don’t get to be a captain by being blind. He looked at Dalton. Then he looked at the captured German, and finally he looked at the faces of the other men.

Men who were alive because this car hadn’t called in artillery. The captain had a choice. He could launch an investigation into unauthorized equipment usage. Or he could accept the victory. Get this vehicle documented, Reed said, turning away. I want photographs and a report. Mark it down. Has non-combat maneuvering accident? Yes, sir. Dalton exhaled.

He had survived the German patrol, and he had survived the American bureaucracy. But as the company’s celebrated word spread quietly through the ranks. Soldiers are gossips. They saw Dalton cleaning mud off a shovel that shouldn’t have been used. They saw the wire in his pack. They connected the dots.

By noon, the official story was that the Germans were bad drivers. But the real story, the one whispered in the chow line, was that Jimmy Dalton had figured out how to trip a tank. And once you know a magic trick works, you don’t just watch it. You want to learn how to do it yourself. Secrets in the infantry don’t stay secret for long. Especially secrets that save lives.

That same afternoon, private Morrison, Dalton’s childhood friend from Gary, cornered him. I saw the wire, Jimmy. I saw the shovels. Dalton didn’t deny it. He just asked if I showed you. Could you keep your mouth shut? That night, under the cover of darkness, the Rusted Shovel School of Anti-Tank warfare held its first class. Dalton taught Morrison the geometry 14in high, 45 degree anchors.

Deadman tension. By March 15th, six men knew the method. By March 20th, the technique had viralized through the underground network of the 34th Division. It wasn’t written down. It wasn’t radioed. It was passed from foxhole to foxhole like contraband. And the results were immediate. On March 18th, a scout car on the road to San Pietro hit Private Jackson’s wire. It flipped, killing the commander.

Jackson cleaned up the evidence before the dust settled. On March 21st, another 222 hit corporal O’Malley’s trap near the Garigliano River. It didn’t flip, but the axle snapped, disabling the vehicle instantly. The crew bailed out and were captured. The Germans were baffled. Lieutenant Klaus Richter, a veteran reconnaissance commander in the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, was the first to realize something was wrong. He inspected the wreckage of three different vehicles.

He found no mine craters, no shell holes, just unexplained rollover damage and deep scratches on the front axles. Richter wrote a report to German intelligence. The Americans have deployed a new, invisible obstacle. It targets the running gear. German high command dismissed it. They couldn’t believe the Americans had a weapon they couldn’t see.

But the drivers believed it. By April, the behavior of the German reconnaissance units changed drastically. They stopped racing down roads. They moved at a crawl. Commanders dismounted to inspect every shadow. The Gray Ghost became timid. This caution broke their effectiveness. A scout car moving at five miles per hour is an easy target for a rifleman.

A scout car that stops to check for wire is a sitting duck. The statistics told a story that the officers at Division HQ couldn’t ignore, even if they didn’t understand it. In February, the division lost 47 men to scout cars. In March, after the wire spread, that number dropped to 12. In April, they lost three three men, down from 47. The artillery strikes, called in by German recon, dropped by 50%.

The 34th Division wasn’t just surviving. They were blinding the enemy. Captain Reed, the clean officer, eventually caught a soldier setting up a wire trap in broad daylight. He watched the man carefully measure the 14 inch height. Reed didn’t scream. He didn’t arrest him. He just pulled out his notebook, sketched the design, and walked away.

He sent a report up the chain validating the methods success rate at 87%. The response from Battalion was swift. Unauthorized discontinue immediately. Reed. Read the order. Then he filed it in the trash. The wire stayed up. The men stayed alive. The bureaucracy had said no. The statistics said yes.

And in war, the only vote that counts is the one that brings you home. James Dalton survived the war. He didn’t come home to a parade, and he didn’t come home to a medal ceremony. The army, in its infinite wisdom, decided that admitting a 19 year old corporal had outsmarted the entire engineering corps was bad for morale. So on November 1945, Dalton was discharged as a sergeant with a Combat Infantryman Badge and a train ticket back to Gary, Indiana. He did exactly what you’d expect a man of his generation to do.

He hung up his uniform, put on his work boots, and went back to the rail yards. U.S. steel hired him as a switchman in January 1946. He spent the next 41 years working the same tracks, fixing the same couplers and splicing the same cables that had taught him how to defeat the Wehrmacht. He married a woman named Dorothy.

They raised three kids, and in all that time he rarely spoke about Italy to his neighbors. He was just Jimmy, the guy who worked the night shift. His obituary in the Gary Post Tribune in 1987 didn’t mention the scout cars. It didn’t mention the 34th Infantry Division. It’s simply said he was a loving father and a loyal employee of U.S. steel.

But the men who were there remembered once a year on March 12th, the anniversary of that first successful trap. Dalton’s phone would ring. It would be Morrison or Williams or Jackson. They would call from across the country just to say hello. They didn’t talk about the war in grand terms. They talked about the mud. They talked about the fog. And they thanked him for the wire.

Conservative estimates suggest that Dalton’s unauthorized method destroyed or disabled 43 German vehicles between March and August 1944. If you do the math on the artillery strikes, those vehicles would have called in. James Dalton likely saved between 300-400 American lives. That is an entire battalion of men who got to come home, get married and meet their grandchildren because the switchman refused to listen to a captain.

The irony, of course, is that the system eventually caught up. In 1949, Army engineers released a revised field manual on anti vehicle obstacles buried in the technical diagrams was a new approved method. Wire obstacles and axle height. The manual credited the innovation to field observations from the Italian campaign. It didn’t name Dalton. It didn’t name the 34th.

It sanitized the history to make it look like part of the plan. But we know the truth. We know that innovation in war doesn’t come from committees in Washington reviewing PowerPoint slides. It doesn’t come from defense contractors with billion dollar budgets. Real innovation comes from the mud. It comes from the corporals who are tired of burying their friends.

It comes from the men who look at a rusted shovel and a piece of scrap wire and see a weapon, simply because they have no other choice. The manual is written by the victors, but the victory is won by the guys who ignore the manual. James Dalton died at 63 from a heart attack in his living room. He was a quiet professional to the end.

But somewhere in the archives of military history, there is a ghost in the machine, a simple rusted wire that proves once and for all that sometimes the guy with the dirty hands is the smartest man in the room. If you found this story compelling, please like this video and subscribe to stay connected with these untold histories.

Leave a comment telling us where you’re watching from. And as always, thank you for keeping these stories alive.

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load