2 MINUTES AGO: JonBenet Ramsey Twist EXPOSES the Audie Murphy Mystery – The Truth Stuns Everyone

Audie Murphy, the boy-faced Texan who became the most decorated American soldier of World War II, was a walking paradox. To the world, he was a hero, a symbol of courage and resilience who had single-handedly held off a company of German soldiers. To those who knew him, and to himself, he was a man haunted by the very demons he had unleashed on the battlefield. His life, a tapestry of extraordinary bravery and profound suffering, is a testament to the unseen wounds of war, the ones that fester long after the guns fall silent.

Born into abject poverty in rural Texas, Murphy’s early life was a relentless struggle for survival. The seventh of twelve children, he was forced to become the man of the house at the age of twelve after his father abandoned the family. With a fifth-grade education and a borrowed rifle, he became a crack shot, not for sport, but to put food on the table. This unforgiving upbringing forged in him a steely resolve and a chilling pragmatism that would later define his military career.

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Murphy, then a skinny, freckle-faced teenager, tried to enlist. He was rejected by the Marines and the Navy for being underweight and undersized. The Army reluctantly took him, initially trying to assign him to a cook and baker school. But Murphy was determined to fight, and through sheer persistence, he was sent to the infantry.

On the battlefields of Europe, Murphy transformed from a boy into a lethal soldier. He saw his first action in Sicily in 1943, and from that moment on, he was a force of nature. He fought with a cold, calculated fury, his small stature belying a ferocity that stunned his comrades and terrified his enemies. He was wounded multiple times, contracted malaria, and saw his friends die, including his best friend, Lattie Tipton. Tipton’s death, in particular, ignited a vengeful rage in Murphy, and he single-handedly wiped out the German machine gun crew that had killed his friend.

The defining moment of Murphy’s military career came on January 26, 1945, near the village of Holtzwihr in eastern France. With his unit decimated and facing an overwhelming German attack, Murphy climbed atop a burning M10 tank destroyer and, for an hour, single-handedly held off the enemy. Wounded and exposed, he used the tank’s .50-caliber machine gun to mow down wave after wave of German soldiers, all while calling in artillery strikes on his own position. His actions saved his men and earned him the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award.

By the end of the war, Murphy had been awarded every combat valor award the U.S. Army had to offer, including two Silver Stars, two Bronze Stars, and three Purple Hearts. He was credited with killing or wounding over 240 enemy soldiers. But the war had taken its toll. The boy who had gone to war was gone, replaced by a man who was emotionally numb and psychologically scarred.

When he returned to the United States, Murphy was a national hero. His face graced the cover of Life magazine, and Hollywood came calling. He was reluctant to embrace the limelight, but with few other prospects, he moved to California and began a new career as an actor. He starred in over 40 films, most of them Westerns, and even played himself in the 1955 film adaptation of his autobiography, “To Hell and Back.” The movie was a huge success, but for Murphy, reliving his wartime experiences on a film set was a form of torture.

Behind the glamorous facade of Hollywood, Murphy was fighting a losing battle with his inner demons. He suffered from severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a condition that was not well understood at the time. He was plagued by insomnia, nightmares, and anxiety. He slept with a loaded pistol under his pillow and was prone to violent outbursts. His first marriage, to actress Wanda Hendrix, lasted only seven months. His second marriage, to Pamela Archer, was also fraught with difficulty. In the later years of their marriage, Murphy lived in a converted garage at their home, a self-imposed exile from a world in which he no longer felt he belonged.

Murphy’s personal struggles were compounded by financial problems. He was a compulsive gambler, and by his own estimation, he lost over $3 million at the racetrack. He made a series of bad investments and, by the late 1960s, he was facing bankruptcy. The man who had once been one of Hollywood’s highest-paid actors was now struggling to make ends meet.

On May 28, 1971, Audie Murphy’s life came to a tragic end. He was a passenger in a private plane that crashed into a mountain in Virginia in foggy weather. He was 45 years old. The official cause of the crash was pilot error, but for those who knew Murphy, his death was the final, inevitable chapter in a life that had been defined by violence and tragedy.

Audie Murphy’s story is a cautionary tale about the cost of war. He was a hero, but he was also a victim. He survived the horrors of the battlefield, only to be consumed by them in the end. His life is a reminder that the wounds of war are not always visible, and that the greatest battles are often fought not on the battlefield, but in the silent, solitary confines of the human heart. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, his grave marked by a simple white headstone, just as he had requested. It is a humble tribute to a man who was anything but ordinary, a man who was both a hero and a casualty of the very war that had made him a legend.

News

You’re Mine Now,” Said the U.S. Soldier After Seeing German POW Women Starved for Days

You’re Mine Now,” Said the U.S. Soldier After Seeing German POW Women Starved for Days May 1945, a dusty processing…

December 16, 1944 – A German Officer’s View Battle of the Bulge

December 16, 1944 – A German Officer’s View Battle of the Bulge Near Krinkl, Belgium, December 16th, 1944, 0530 hours….

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost On March 17th, 1943, in a quiet woodpanled…

They Mocked His “Caveman” Dive Trick — Until He Shredded 9 Fighters in One Sky Duel

They Mocked His “Caveman” Dive Trick — Until He Shredded 9 Fighters in One Sky Duel Nine German fighters circle…

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost On March 17th, 1943, in a quiet woodpanled…

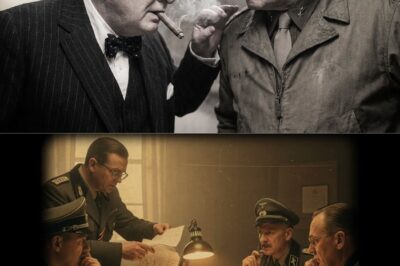

What Churchill Said When Patton Reached the Objective Faster Than Any Allied General Predicted

What Churchill Said When Patton Reached the Objective Faster Than Any Allied General Predicted December 19th, 1944. The war room…

End of content

No more pages to load