Uncover the sh0cking truth behind Dale Earnhardt’s tragic cr4sh that changed NASCAR forever — the secrets hidden for decades, the hau.nting final moments before impact, the mysterious chain of events that investigators never revealed, and the mind-blowing discoveries that will completely transform how you see this legendary racer’s final ride.

On February 18, 2001, the world of motorsports was irrevocably altered. It was a sun-drenched day at the Daytona International Speedway, a day meant to be a landmark celebration for NASCAR. With a brand-new, billion-dollar broadcasting deal with Fox Sports, the 2001 Daytona 500 was poised to bring stock car racing to millions of new fans. The stands were electric, packed with nearly 150,000 spectators, all there to witness the high-octane drama unfold. At the center of it all was the sport’s most iconic figure, a man whose legend was as much about his fearless persona as his seven championships: Dale Earnhardt, “The Intimidator.” No one in that roaring crowd could have imagined that in a matter of hours, they would bear witness to the final, tragic moments of his life.

The story of that day, however, began long before the green flag dropped. It was woven with threads of eerie premonitions, ignored warnings, and a profound, uncharacteristic emotional shift in a man known for his stoic, tough-as-nails demeanor. Just two days before the race, during a television interview with his former rival Daryl Waltrip, Earnhardt did something unusual. He suddenly jumped from his chair, arms thrown wide, and shouted with raw emotion, “I’m a lucky man. I’ve got it all.” He spoke with heartfelt sincerity about his wife, his children, and the incredible speed of his race cars. For those who knew him, it was a startlingly sentimental display, a public vulnerability that felt, in hindsight, like an unconscious farewell.

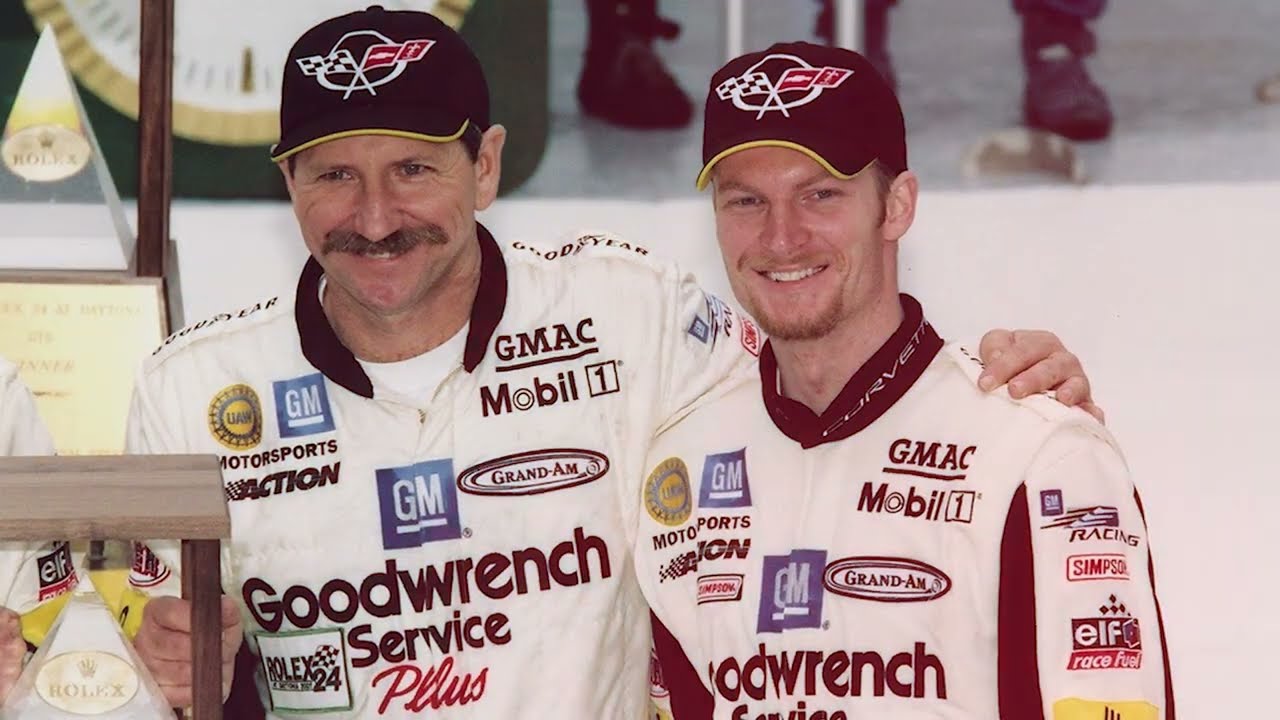

The strange premonitions continued. The night before the race, during a business meeting with fellow driver Terry Labonte, Earnhardt concluded their discussion about a promising deal with a chillingly offhand remark. “That’s if I make it that far,” he muttered. While everyone else laughed it off as Dale’s signature dark humor, he remained quiet, distant. On the morning of the race, he approached his son, Dale Earnhardt Jr., not with his usual stoicism, but with a rare moment of paternal encouragement. “We’re going to do this together,” he said, a simple gesture that would become a cherished, final memory for his son.

Beneath these personal moments, a more significant and deadly conversation was unfolding within NASCAR’s inner circle—one that Earnhardt actively resisted. In the 12 months leading up to the Daytona 500, three promising young drivers—Adam Petty, Kenny Irwin Jr., and Tony Roper—had all been ki.lled by the same devastating injury: a basilar skull fracture. This injury, caused by the violent whiplash effect of a high-speed crash, had become a terrifying pattern. In response, safety experts were desperately pushing a new, life-saving innovation called the HANS (Head and Neck Support) device. Made of carbon fiber, it was designed to stabilize a driver’s head and neck during an impact, preventing the very injury that had proven so fatal.

But Dale Earnhardt wanted no part of it. A traditionalist who relied on instinct and feel, he found the device restrictive and uncomfortable. When asked if he would wear one, his response was blunt and became tragically ironic: “I ain’t wearing that damn noose.” NASCAR even held a special safety demonstration at Daytona, featuring one of the nation’s leading experts. Drivers like Dale Jarrett and Bill Elliott attended, getting fitted for the device just feet from Earnhardt’s garage. Dale stayed away. On race day, out of 43 drivers, only five wore the HANS device. One of them was Kyle Petty, still grieving the loss of his son, Adam, to the exact injury that would claim Earnhardt’s life just hours later.

The race itself was a spectacle of chaos and intensity, a perfect embodiment of the sport Earnhardt had come to define. For much of the race, he was in peak form, surging to the front of the pack four different times, each pass met with a deafening roar from the crowd. But with just 25 laps to go, the day took a violent turn. A massive pileup on the backstretch collected 20 cars, nearly half the field. At the center of the carnage was Tony Stewart’s bright orange car, which slammed head-on into the wall with terrifying force, flipping through the air before coming to a rest in a mangled heap of metal. Miraculously, Stewart walked away, bruised but alive. Watching the chaos unfold, Earnhardt got on the radio to his team owner, Richard Childress. His voice was serious, almost prophetic. “Richard,” he said, “they’re going to have to do something about these cars, or they’re going to get somebody ki.lled.”

As the race neared its conclusion, something shifted in Earnhardt’s strategy. For the first time in his legendary career, he wasn’t racing for himself. He was racing for his family and his team. His son, Dale Jr., and his longtime friend and driver, Michael Waltrip, were running in first and second place. With just a handful of laps remaining, Dale’s iconic black No. 3 Chevrolet transformed into a mobile fortress. His mission was clear: protect the two cars ahead of him at all costs. In an almost unthinkable move, he briefly took the lead, only to lift off the gas, allowing Waltrip and Junior to pass.

For the next 17 laps, Earnhardt put on a masterclass in defensive driving. At nearly 180 mph, he weaved left and right, blocking every challenge from charging competitors like Sterling Marlin and Rusty Wallace. It was a selfless, dangerous dance on the edge of disaster. His plan worked. As the white flag waved, signaling the final lap, Waltrip and Junior had a comfortable lead. But in protecting them, Earnhardt had placed himself in the most vulnerable position on the track—right in the middle of the storm.

Entering the final turn, Sterling Marlin made one last desperate move, diving low to get under Earnhardt. Dale instinctively dropped down to block him. The contact was minuscule, a slight tap from Marlin’s car to Earnhardt’s rear quarter panel. But at that speed, it was enough. Earnhardt’s car veered left, then shot back up the banking directly into the path of Ken Schrader. The impact was violent, sending both cars hurtling toward the outside wall at nearly 160 mph.

To the millions watching, it looked like a routine last-lap crash. But the physics of the impact were brutal. The car hit the concrete barrier at a deadly diagonal angle, subjecting Earnhardt’s body to a catastrophic deceleration of over 40 mph in just 80 milliseconds, with forces registering nearly 60 Gs. The impact shattered his left lap belt, which was later found to be worn and frayed, snapping it clean apart. His body was thrown with immense force, and his head whipped forward, causing the fatal basilar skull fracture.

Ken Schrader, whose car had come to a stop beside Earnhardt’s, knew instantly that something was terribly wrong. He rushed to Dale’s window, and what he saw would haunt him for the rest of his life. To this day, he has never publicly described the scene, only saying, “I just knew that it wasn’t good.” He began waving frantically for the safety crews, the first public sign that this was no ordinary crash.

Medical teams worked desperately on the track and later at Halifax Medical Center, but it was too late. Dale Earnhardt was pronounced dead. In victory lane, Michael Waltrip celebrated his first-ever Daytona 500 win, completely unaware of the tragedy that had befallen the man who made it possible. Dale Jr., after finishing second, sensed the horror when he saw the look on Ken Schrader’s face and ran to the hospital, where his worst fears were confirmed. The Intimidator, the man who seemed indestructible, was gone. The loss sent a shockwave through the world, and in its wake, NASCAR was forced into a new era of safety, finally mandating the very device that Dale Earnhardt had so tragically refused.

News

You’re Mine Now,” Said the U.S. Soldier After Seeing German POW Women Starved for Days

You’re Mine Now,” Said the U.S. Soldier After Seeing German POW Women Starved for Days May 1945, a dusty processing…

December 16, 1944 – A German Officer’s View Battle of the Bulge

December 16, 1944 – A German Officer’s View Battle of the Bulge Near Krinkl, Belgium, December 16th, 1944, 0530 hours….

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost On March 17th, 1943, in a quiet woodpanled…

They Mocked His “Caveman” Dive Trick — Until He Shredded 9 Fighters in One Sky Duel

They Mocked His “Caveman” Dive Trick — Until He Shredded 9 Fighters in One Sky Duel Nine German fighters circle…

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost On March 17th, 1943, in a quiet woodpanled…

What Churchill Said When Patton Reached the Objective Faster Than Any Allied General Predicted

What Churchill Said When Patton Reached the Objective Faster Than Any Allied General Predicted December 19th, 1944. The war room…

End of content

No more pages to load