The road burned under the noon sun. Dust rose around Ida Mabel’s ankles with every step she took. The air shimmerred with heat, bending the horizon into a silver blur. Her throat achd from thirst, and her worn sandals cut into her swollen feet, but she kept walking. Stomping meant thinking, and thinking hurt worse than the sun.

She had been walking since dawn, clutching an old suitcase that held little more than a few clothes and too many memories. Behind her, the small village of San Barlo faded into the heat along with the angry voice that had sent her away that morning. “A thief and a liar,” Donatamasa had shouted. Mabel could still hear it.

10 years she had worked for that family, sewing, mending, cleaning. Her hands cracked and bleeding from years of service. She’d stitched their dresses, embroidered their tablecloths, even sewn the baptism cloth for their youngest child. Yet one piece of lace went missing, and suddenly she was the villain. No husband, no family, no one to defend her name.

Just the word thief echoing in her ears. She stopped beside a dry agave plant and sank to her knees, chest heaving. The air smelled like salt and sand. Above a vulture circled, lazy and patient. “God,” she whispered, pressing her hands together. “Please don’t let me die here. Not like this.” Then came a sound, steady, rhythmic, hooves, a creaking wheel.

She looked up and saw a cart in the distance, a brown horse pulling it slow and sure. A tall man sat at the rains and several small figures huddled behind him. Mabel hesitated. Strangers could mean trouble, but the cart slowed, then stopped beside her. The man’s face was shaded under a wide hat. His beard was neat, stre with gray.

His shirt was clean but worn like someone who worked hard and didn’t waste words. “Senorita,” he said, voice deep and calm. “Are you hurt?” Mabel shook her head. “Just tired,” she said. “It’s a long walk to the next town.” The man stepped down from the cart, boots pressing perfect marks in the dust. Five girls peeked from behind him, their faces full of curiosity.

“Where are you headed?” he asked. South, Mabel said quietly. Maybe Santa Cruz. Maybe somewhere that doesn’t know my name. He nodded slowly. That’s 20 km at least. On foot. You won’t make it before nightfall. She didn’t reply. What could she say? A small voice broke the silence.

Papa, she looks sad, said one of the girls. The man looked at his daughter, then back at Mabel. What’s your name? Eda Mabel, she said. Just Mabel. He adjusted his hat. I’m Dante Adoro. I have a ranch a few miles west of here. Five daughters. He motioned toward the cart. I could use help around the house. Mabel frowned. You don’t even know me. He shrugged.

No, but I know what it’s like to need a chance. The words landed deep inside her chest. No one had ever spoken to her like that. Not with pity, not with suspicion, but with understanding. What kind of work? She asked. housekeeping, cooking, watching the girls when I’m out with the livestock. You’ll have food, a room, and fair pay.

” Mabel hesitated. “Are you sure?” she asked. “I’m not what people expect.” Teodoro almost smiled. “Neither am I.” Quote. One of the youngest girls giggled and reached out a tiny hand. “Come, Senora,” she said. “We have chickens.” Something inside Mabel cracked, not from sadness, but from remembering what kindness sounded like.

She picked up her suitcase and whispered, “All right, I’ll come.” Teodoro helped her onto the cart. The wood creaked under her weight, but none of the girls laughed. The smallest nestled against her side as they rolled on. The horizon stretched wide and pale. Mabel held her suitcase close. She didn’t know if she was heading toward hope or heartbreak, but at least she was moving.

After some time, she asked, “Why are the girls so quiet? They’ve had too many people come and go,” Teodoro said. “They don’t talk much to strangers anymore.” “Then I’ll try to stop being one.” He glanced at her, a flicker of something like approval in his eyes. The youngest, Luna, tugged at Mabel’s sleeve. Are you going to live with us now? Mabel smiled faintly.

Looks like it. Good. Luna whispered. We need someone who sings. Mabel blinked. Sings. Uh-huh. Mama used to sing when it rained. The house doesn’t like the silence. The word stayed with Mabel as the cart turned off the main road. The ranch came into view. A wooden house standing alone against the red evening sky. Fields stretched dry, but waiting.

Mabel swallowed hard. It looked like a place that wanted to be home again, but didn’t know how. When the cart stopped, Teodoro climbed down first, then helped Mabel to the ground. The boards of the porch creaked underfoot. The air smelled of hay and old wood. The door opened suddenly, and a teenage girl stood there, arms crossed, eyes sharp.

She won’t last a week,” she said in Spanish. Mabel met her gaze and gave a small nod. “Maybe not, but I’ll give it my best.” The man’s silence spoke louder than words. He showed her to a small room with a plain bed and a single window facing the hills. “It’s not much,” he said. “It’s enough,” Mabel replied softly.

That night, she cooked stew from whatever she found. beans, onions, a pinch of herbs. The girls hovered in the hallway, half curious, half unsure. Mabel served them first, then Teodoro. No one said much until Luna whispered, “Gracias!” For the first time in days, Mabel smiled. As the moonlight slid across the floorboards, she sat alone at the kitchen table, listening to the wind outside.

The house was quiet, but not empty. It felt like it was waiting, like her, and though Mabel didn’t know it yet, that waiting was about to end. Morning came with the cry of a rooster and the smell of wet dirt. It had rained a little before dawn, just enough to soften the ground and quiet the dust. Eda Mabel rose before anyone else.

Her body achd, but it was the kind of pain that reminded her she was still alive. She tied her hair back with a ribbon, washed her face in cold water, and stepped outside. The garden behind the house was a tangle of weeds and forgotten tools. She knelt beside a patch of dry soil and ran her fingers through it.

It was rough, stubborn, but not dead. “We’ll start with you,” she whispered. She began clearing away broken branches, her hands moving steady and sure. An hour passed before she heard footsteps. It was No, one of the middle girls. the quiet one with dark curls. She stood there holding a glass of water. “Papa says you shouldn’t work so early,” she said. Mabel smiled.

“The Earth doesn’t wait for anyone, Nia.” No answer, but she left the glass beside her and went back inside. When the sun climbed higher, Mabel had cleared a whole corner of the garden. Sweat trickled down her neck, and her dress clung to her back, but her chest felt lighter. For the first time in weeks, she had purpose.

Inside the house, the oldest girl, Leah, watched from the upstairs window. Her jaw was tight, her eyes unreadable. In her hands, she held a small wooden box. She opened it just enough to see what was inside. Packets of old seeds her mother had once kept. Then she shut it again. By noon, Mabel returned to the kitchen.

The house smelled faintly of soap and smoke. She made coffee and began cooking lunch, fried plantains, eggs, and fresh tortillas. When the girls came down, they hesitated before sitting. Mabel didn’t rush them. She set the food on the table and said simply, “Eat.” Quote, “They did, even Leah,” though she didn’t meet her eyes. After the meal, the girls scattered, some to chores, others to the porch.

Mabel washed dishes at the sink. She could feel the house watching her, testing her, wondering if she’d last. In the late afternoon, she found Leah outside standing near the clothesline with that same wooden box in her hands. “What’s that?” Mabel asked. “Nothing,” Leah said quickly. “Just something Mama left.” Quote. Mabel nodded.

“You miss her.” Leah’s voice was sharp. You wouldn’t understand. Maybe not your way, Mabel said. But I understand missing people who should have stayed. Leah looked at her, surprised by the calm in her tone. You talk too much, she muttered. Maybe, Mabel said, but only when it matters. Later, while sweeping the floor, Mabel heard faint crying from upstairs.

She went up quietly and found Sarah, one of the younger girls, sitting by the window, her knees pulled to her chest. “Bad dream?” Mabel asked. Sarah wiped her face. “Leah says mama left because we were too much trouble.” Mabel knelt beside her. “Mama left because grown-ups make bad choices, not because of you,” Sarah sniffed.

“Do you think she’ll come back?” “No,” Mabel said softly. but you’ll be okay anyway.” Sarah leaned into her, small and trembling. Mabel wrapped an arm around her and hummed an old tune her own mother used to sing. The girl’s breathing slowed, and for a moment, the air in the room felt almost safe. That night, while everyone slept, Mabel went back outside.

The moon hung low, and the garden glowed silver. She carried a lantern and the wooden box Leah had left on the porch. Inside were seeds, beans, maragolds, squash, and one marked floor day. Mabel smiled and began pressing them into the soil. By morning, Leah found her still there covered in dirt. What are you doing? She demanded. Starting something new, Mabel said.

You can’t just take her seeds. I didn’t take them, Mabel said. I’m giving them a chance. Leah stood silent for a long moment. Then she crouched down beside her. “She never planted them,” she whispered. “Maybe she was waiting for the right season,” Mabel said. Leah handed her another packet. “Then let’s see if they still remember how to grow.

” Together, they worked until the sun burned through the clouds. By the time they finished, six neat rows stretched across the garden. The girls came running to see. Luna clapped her hands. Sarah said it smelled like rain. No brought a picture of water and poured it carefully over the rose. When Teodoro returned from the fields, he stopped in surprise.

“What’s this?” “Our garden,” Mabel said. Leah straightened. “Mine and hers.” Teodoro nodded, his face unreadable. “It’ll need fencing.” “Rabbits will get to it.” “We’ll build one,” Mabel replied. That night, laughter returned to the dinner table. It was small, uncertain, but real. Luna told a story about a chicken that tried to sit on a cat.

Sarah pretended not to laugh, but her shoulders shook. After the dishes were done, Mabel stepped out to the porch. The wind carried the soft clinking of the new windchime she’d found in the shed. Teodoro joined her, leaning against the railing. “You’ve done more in a week than anyone since she passed,” he said quietly. Mabel didn’t turn.

“I didn’t come to fix a house, Don. Teodoro, I came because I had nowhere else to go. He looked at her, his eyes steady. Maybe that’s exactly why you’re the one who can. Mabel stared at the dark field stretching beyond the fence. Somewhere out there, coyotes called. But for the first time in a long time, she wasn’t afraid of the dark.

Because inside, there was light again. The storm came without warning. The wind howled through the valley, bending the trees and slamming shutters against the walls. Rain pounded the roof like an army trying to break through. Eda Mabel stood in the doorway, holding the frame steady as lightning flashed over the hills. “Stay inside!” she shouted, her voice cutting through the noise.

“The girls clung together near the hearth, eyes wide.” Teodoro ran past her toward the barn. “The horses!” he yelled. “If the doors give, they’ll break their legs. Without thinking, Mabel grabbed her shawl and ran after him. The rain was cold and heavy, soaking her dress within seconds. The mud pulled at her boots as she reached the barn.

Teodora was fighting to tie the gate, his hands slipping on the wet rope. Together, they pushed until the doors slammed shut. For a moment, they just stood there, breathless, faces inches apart, the storm screaming around them. “You didn’t have to come out here,” he said. Mabel wiped water from her face. “You’d do the same for me.

” Lightning cracked again, white and wild. The horses stomped nervously. Teodoro grabbed her hand. “Come on,” he said. “We’ll ride it out inside.” By the time they got back, the girls had built a small fire in the kitchen. Luna was crying softly, holding her stuffed donkey. Mabel knelt and pulled her close. “It’s only rain, baby,” she whispered.

“The house is strong.” The night dragged on. Thunder rolled over the hills like drums. Mabel sang softly, an old song her mother used to hum. The words didn’t matter. The sound alone was enough. One by one, the girls fell asleep against her. When dawn finally broke, the storm had passed. The ranch was a mess.

Fences bent, branches scattered, but it was still standing. So were they. Teodoro came in from checking the damage, his hat dripping. We lost a few posts, but the animals are fine, he said. Could have been worse. Mabel poured him coffee. Well fix it. He nodded. We will. His eyes lingered on her for a moment. You kept them safe. They keep me safe, she said softly.

Later that morning, Leah came running from the garden. The plants, she cried. Mabel followed her outside. Rows of soil stretched in front of them, drenched and torn by wind. Most of the seedlings were gone. Leah dropped to her knees, tears mixing with rainwater. They’re ruined. Mabel knelt beside her.

Not ruined, she said, brushing her hand across the mud. Some roots are still alive. Leah shook her head. You don’t know that. I do, Mabel said. The ground always gives back if you keep trying. Together, they worked to fix what they could, replanting the seeds that hadn’t washed away. Soon Sarah and No joined, followed by Luna carrying a bucket of water almost too big for her arms.

Even Teodoro came, hammering broken posts back into place. By afternoon, the garden looked like itself again, not perfect, but alive. That night, after dinner, Teodoro sat beside Mabel on the porch. The air was cool and sweet after the rain. The stars blinked faintly through the thinning clouds. You know, he said, “You’ve changed this place.

” Mabel smiled faintly. “No, the place changed me.” He looked at her hands, scarred, steady, gentle. “When I first saw you on that road, I didn’t know why I stopped. I just knew I couldn’t leave you there. Now, I think maybe that was the day everything started over.” She turned her gaze to the dark fields.

“You don’t owe me anything, Danteo.” He shook his head. Maybe not, but I’m grateful anyway. Silence stretched between them, not heavy, but full. Somewhere inside the house, the girls laughed in their sleep. Weeks passed, and the ranch began to heal. The garden sprouted again. Leah taught Luna how to read.

Sarah learned to carve small wooden animals. No started painting the old barn walls with bright colors, flowers, birds, sunlight. The house no longer echoed. It sang. Then one morning, as Mabel hung laundry in the yard, a rider appeared down the road. She narrowed her eyes. The horse was unfamiliar.

When he stopped near the gate, Mabel’s stomach tightened. It was Barollo Cortez, the man who had cheated Teodoro years ago. His smile was smooth as oil. Heard the Espinosa ranch got itself a new woman in charge, he said. Thought I’d come congratulate you. Teodoro came out of the barn, face hard. You’re not welcome here. Barollo shrugged.

“Business never dies, old friend. I came to collect what’s owed.” “You stole from me,” Touadoro said. “You got nothing coming but dust.” Barollo’s eyes slid toward Mabel. “Maybe she could make things right. A woman like that knows the value of peace.” Mabel’s hands clenched, but her voice stayed calm. “I know the value of work. You wouldn’t understand.

” He smirked. “Careful, big girl. Not everyone likes a woman who talks like a man. Quote, Before Teodora could move, Mabel stepped forward, and not everyone survives calling me that twice. Something in her tone made him flinch. He spat on the ground and climbed back on his horse. “This place won’t last,” he said.

“Then you’ll be disappointed,” Mabel replied. When he rode away, the dust he left behind settled slow, but the resolve didn’t. That evening, Mabel stood in the garden, looking at the small green shoots pushing through the soil again. Teodoro joined her. “He’ll come back,” she said. “I know. We’ll be ready.” He nodded. “We always are.

” The sun dipped low and the sky burned gold. Mabel took a deep breath of earth and air. She thought of the road that had brought her here, of the word thief that once clung to her name, of the girls laughter now echoing from the porch. She wasn’t the woman who’d beg God not to let her die alone on the road. She was the woman who had built a home from dust.

Theodoro watched her a moment longer, then said quietly, “You needed a roof. I needed someone who wouldn’t leave. Looks like we both got what we were looking for. Mabel smiled, eyes glistening in the fading light. No, she said softly. We got more than that. We got a family. And as the last light fell over the ranch, the wind carried the faint sound of laughter, the kind that stays.

News

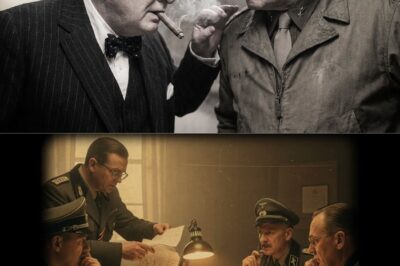

You’re Mine Now,” Said the U.S. Soldier After Seeing German POW Women Starved for Days

You’re Mine Now,” Said the U.S. Soldier After Seeing German POW Women Starved for Days May 1945, a dusty processing…

December 16, 1944 – A German Officer’s View Battle of the Bulge

December 16, 1944 – A German Officer’s View Battle of the Bulge Near Krinkl, Belgium, December 16th, 1944, 0530 hours….

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost On March 17th, 1943, in a quiet woodpanled…

They Mocked His “Caveman” Dive Trick — Until He Shredded 9 Fighters in One Sky Duel

They Mocked His “Caveman” Dive Trick — Until He Shredded 9 Fighters in One Sky Duel Nine German fighters circle…

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost

March 17 1943 The Day German Spies Knew The War Was Lost On March 17th, 1943, in a quiet woodpanled…

What Churchill Said When Patton Reached the Objective Faster Than Any Allied General Predicted

What Churchill Said When Patton Reached the Objective Faster Than Any Allied General Predicted December 19th, 1944. The war room…

End of content

No more pages to load