April 23rd, 1943. Camp Hood, Texas. The sun beat down on the wire fence like a hammer on an anvil. Inside the compound, a young Japanese soldier named Hiroshi Tanaka pressed his face against the chain link, staring at the endless messed hills rolling toward the horizon. Behind him, 200 prisoners shuffled through evening roll call.

Before we continue, hit like and subscribe and tell us where you’re watching from. Tokyo, Texas, or anywhere between. This story spans oceans and decades. And we’re grateful to have you here with us right now. Now, back to that Texas evening in 1943. Tanaka had been a prisoner for 7 months. But as the guard turned his back and the dust devils danced beyond the wire, he made a decision that would erase him from history.

He would not return to Japan. He would not return to the barracks. And in that moment, he realized that survival meant becoming someone else entirely. The war in the Pacific had been raging for nearly 2 years. When Tanaka arrived at Camp Hood, he’d been captured during the Illusian campaign, one of the first Japanese soldiers taken alive in a conflict where surrender meant dishonor worse than death. The statistics were staggering.

Of the roughly 140,000 Japanese military personnel who became prisoners during World War II, fewer than 1% surrendered voluntarily. Most were captured while unconscious or too wounded to resist. The cultural weight of Bushidau, the warrior code made capitulation unthinkable. To return home after surrender was to return as a ghost, dead to family and country.

Camp Hood sprawled across 200,000 acres of central Texas grubland. It had been built in 1942 to train tank destroyer battalions, but by 1943 a section had been converted to house access prisoners. The Japanese were kept separate from German and Italian po. Language barriers made integration impossible.

Cultural differences made it dangerous. Tanaka spent his days hauling rocks, mending roads, and learning fragments of English from guards who treated him with a mixture of curiosity and contempt. At night, he lay on his cart and listened to the coyotes howl across the hills. He thought often of his village outside Hiroshima. His father had been a fisherman, his mother a seamstress.

He’d been conscripted in 1940, trained on Hokkaido, and shipped to the Illusions in early 1942. The cold there had been biblical. Men froze to their rifles. Frostbite claimed more casualties than bullets. When American forces landed on Atu Island in May 1943, Tanaka had been part of a supply unit caught in a mountain pass. An artillery shell had knocked him unconscious.

He’d woken in an American field hospital with his hands bound and his honor shattered. But Texas was different from Alaska. Texas was warm. The land breath, and the guards rotated frequently, were often young farm boys who barely understood the war they were guarding. One evening in late April, Tanaka noticed something. The northwestern perimeter where the fence met a dry creek bed was watched by a single tower.

The guard on duty that night was a kid from Oklahoma named Jimmy Curtis. Curtis had a habit of reading pulp westerns during his shift. Tanaka had observed this for 3 weeks. He knew Curtis turned pages every 4 to 6 minutes. He knew the sun set behind the tower at 7:47 p.m. blinding anyone looking west. On April 23rd, Tanaka made his move.

He’d saved a piece of wire from the motorpool. During evening formation, he slipped away from the line and crawled toward the fence. The ground was hard and cracked. Dust clung to his sweat. He reached the chain link just as the sun dropped behind Curtis’s tower. The wire parted under his makeshift tool with a soft metallic whisper.

He slipped through. No shout came. No siren wailed. He ran. The mkuit and cedar swallowed him within minutes. By the time roll call revealed his absence, Hiroshi Tanaka had vanished into 200,000 acres of Texas wilderness. The MPs launched a search that lasted 2 weeks. Dogs tracked him to a creek 5 mi north, then lost descent in the water.

Helicopters swept the hills. Roadblocks went up on every highway within 50 mi. They found nothing. The official report filed in May 1943 listed Tanaka as escaped presumed dead in wilderness. The case was closed, but Tanaka was not dead. He was hiding in a limestone cave 7 mi northwest of the camp, surviving on creek water and prickly pear cactus.

He’d learned about the cave from another prisoner, a man who’d worked on a ranch crew before the war. The cave was cool, hidden by cedar brakes, and unknown to the local ranchers. Tanaka stayed there for 2 months, emerging only at night to forage. He caught fish with his hands. He ate me beans.

He watched the stars wheel overhead, and wondered if he would ever see another human being. In late June, desperation drove him out. He’d grown weak. His clothes were rags. He needed food, real food, or he would die. He began moving south away from the camp, staying off roads and avoiding farms. On the night of June 28th, he stumbled onto a ranch 30 mi south of Camp Hood.

It was a small operation 300 acres, a modest house, a barn owned by a widowerower named Earl McCulla. McCulla was in his 60s, a former cavalry officer who’ retired to raise cattle after World War I. He was also half deaf from artillery exposure, which is why he didn’t hear Tanaka slip into his barn that night. Tanaka found sacks of cornmeal, a ham wrapped in cloth, and a jug of water.

He ate like a wolf, crouched in the dark between hay bales. When he finally looked up, Earl McCulla was standing in the doorway with a lantern in one hand and a revolver in the other. The old man’s face was unreadable. He stared at the skeletal figure in rags, then lowered the gun. He said one word. “Hungry?” Tanaka understood the tone, if not the language. He nodded.

McCulla turned and walked back toward the house. After a long moment, Tanaka followed. What happened next defied every regulation in the US military handbook. Macala fed Tanaka a meal of beans, cornbread, and coffee. He gave him a blanket and let him sleep in the barn. In the morning, he brought him soap and clean clothes worn ranch ear that hung loose on Tanaka’s frame. They did not speak much.

Mikallo’s English was Texan draw. Tanaka’s English was fractured and minimal, but they communicated through gestures and work. Makulla needed help mending fences, hauling feed, and clearing brush. Tanaka needed food, shelter, and invisibility. An unspoken agreement formed. Tanaka worked the ranch for 3 years.

He learned to rope cattle, brand calves, and repair windmills. He slept in a small shed behind the barn. Mccala never asked about his past. Tanaka never offered. The war raged on Saipan Ewima Okinawa, but it felt distant, abstract. Radio reports reached the ranch, but Tanaka understood little, and Makulla commented less.

In August 1945, when news of Hiroshima’s destruction crackled over the airwaves, Tanaka was replacing a fence post 3 mi from the house. He did not learn what had happened to his city until 2 days later. Makulla told him simply, “Wars over. Japan surrendered.” Tanaka sat down in the dirt and did not move for an hour.

He asked Makulla if he should turn himself in. The old man shook his head. Where would you go? He said, “Japan don’t want you. Army don’t need you. You got a place here.” It was the most Makulla had said in months. Tanaka stayed. Over the next 2 years, Makulla taught him English with a patience that bordered on fatherly. Tanaka learned to read livestock auction notices, weather reports, and eventually warm copies of Zay Grey novels McCulla kept on a shelf.

He learned American idioms, Texas slang, and the rhythms of ranch life. He also learned to hide in plain sight. When neighbors visited, Tanaka became Harry, a hired hand from California. His features and accent raised eyebrows, but Mechallo’s reputation as a straight shooter kept questions shallow. Harry was quiet, hardworking, and kept to himself.

In a state still scarred by war, that was enough. By 1950, Tanaka had saved enough money to buy a small parcel of land adjacent to Michel’s ranch. He registered the deed under the name Harold Tekashi Thompson, a fabricated identity that blended his heritage with American convention. The county clerk barely glanced at the paperwork.

The 1950s passed in a rhythm of cattle sales, droughts, and fence repairs. McCulla died in 1957, leaving Tanakan, now known universally as Harry Thompson, his ranch in a handwritten will. Lawyers questioned the bequest, but no relatives contested it. Tanaka expanded the property, adding another 100 acres over the next decade.

He married in 1962, a quiet woman named Linda, who worked at the county library. She knew he was Japanese. She never asked how he’d ended up in Texas. They had two children, a boy and a girl. Both raced speaking English and riding horses before they could read. By 1970, Hurray Thompson was a fixture in the community.

He served on the school board. He judged livestock at the county fair. He sponsored a little league team. His past had been sanded smooth by time and routine. Even his children knew only fragments. Dad came from Japan. Dad worked hard. Dad didn’t talk much about the war. The details had dissolved into the limestone dust of the Texas hills.

And then in 1978, a researcher from the University of Texas arrived in town. Her name was Dr. Ellen Kaufman, and she was compiling oral histories of World War II P camps in Texas. She’d been reviewing old military records and had noticed discrepancies in Camp Hood’s escape reports. One name kept appearing in footnotes.

Hiroshi Tanaka, escaped April 1943, presumed dead, but no death certificate had ever been filed. No remains had been found. Kaufman’s academic curiosity turned into obsession. She began interviewing locals who’d lived near the camp during the war. Most remembered nothing useful, but one elderly woman mentioned a strange fella who’d worked for Earl McCulla back in the 40s.

Kaufman followed the lead. She found Mick Cull’s property records, traced the deed to Harry Thompson, and cross-referenced Thompson’s naturalization papers. The dates didn’t align. Thompson claimed to have immigrated in 1946, but no entry records existed. His social security number had been issued in Texas, not California, and his age matched Tanaka’s almost exactly.

Kaufman drove out to the ranch on a scorching July afternoon. Harry Thompson met her at the gate. He was 73 years old, lean and weathered, with silver hair and hands like cured leather. She introduced herself. She explained her research. She asked very carefully if he’d ever heard of a Japanese P named Hiroshi Tanaka.

Thompson stared at her for a long moment. Then he smiled, a sad, distant expression. Haven’t heard that name in 35 years, he said. They sat on the porch for 3 hours. Thompson told her everything. The escape, the cave, Makulla, the slow transformation from prisoner to rancher. He showed her documents, his original Japanese military identification, hidden in a tin box in the barn.

He showed her letters he’d written to his family in Hiroshima, but never sent because he’d learned in 1946 that his entire village had been vaporized. Kaufman asked if he regretted his decision. Thompson shook his head. “I regret the war,” he said. “I regret what happened to my family, but I don’t regret surviving.

” She asked if he wanted to go public. He thought about it. Then he shook his head again. I’m Harry Thompson now, he said. I’ve been Harry longer than I was Hiroshi. Kaufman respected his wishes. She published her findings in an academic journal under a pseudonym changing identifying details to protect his identity.

The article appeared in 1979 titled the invisible veteran, a case study in P integration. It was read by approximately 300 scholars and forgotten by history. Harry Thompson continued ranching until 1985 when a stroke forced him to sell the property. He moved into a small house in town with Linda. His children took over parts of the land.

He spent his final years reading, gardening, and occasionally attending Rotary Club meetings. He died in 1991, age 86, surrounded by family. His obituary listed him as Harold T. Thompson, rancher and community leader. It made no mention of Japan camp or the war. At his funeral, over 200 people gathered.

They remembered him as a fair employer, a devoted husband, and a man who kept his word. But his daughter found something while sorting his belongings. She had come to his house in the days after the funeral, moving through the rooms, slowly touching the objects he had touched, feeling the quietness gather around her like dust. He had lived simply never worn for souvenirs or the sentimental, so she expected to find little more than old receipts, worn flannel shirts, and the tools he kept sharpened even in old age.

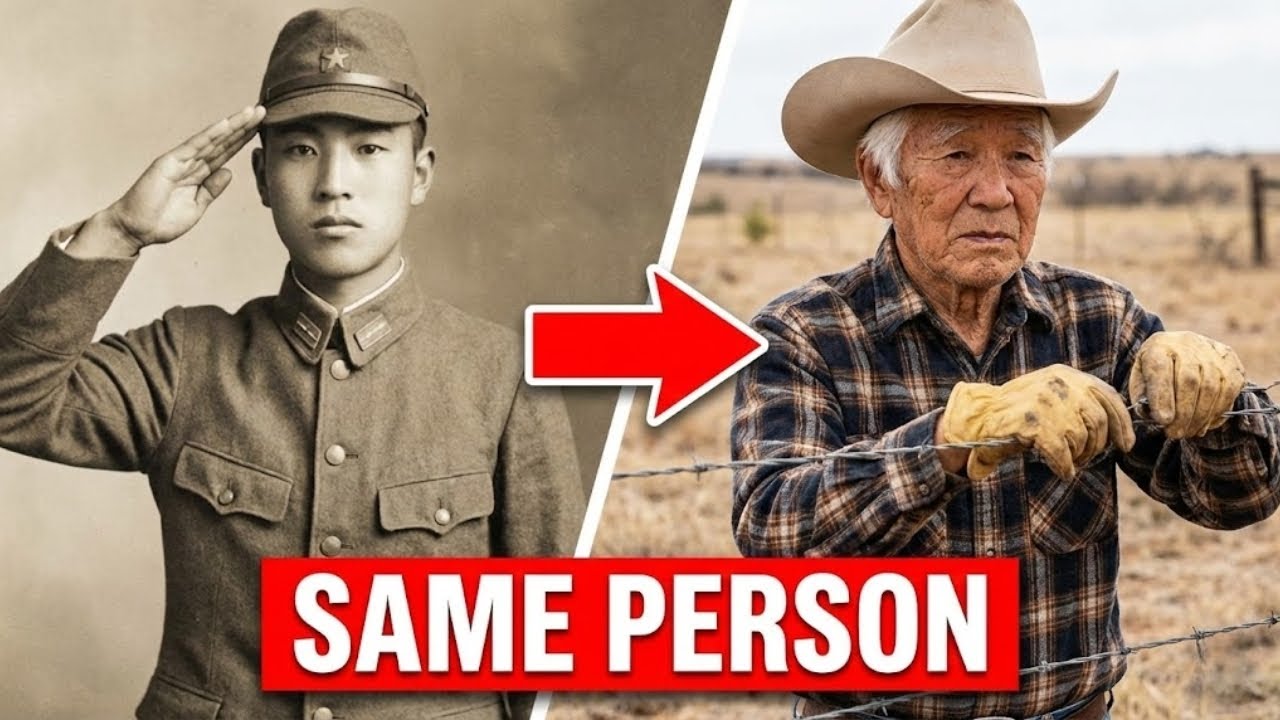

Yet in the back of a closet, wrapped in oil cloth stiff with time, was a small wooden box, no larger than a bread loaf. It was tucked beneath a stack of yellowing blankets, as though hidden decades earlier, with deliberate care. Inside was a photograph of a young man in an Imperial Japanese Army uniform, the face leaner and sharper than the one she had known.

There was a letter written in Japanese, the paper brittle at the edges, the ink faded to a soft gray, and beneath it, folded with a precision bordering on reverence, lay a creased map of Camp Hood, the place where her father, as she had always known him, had never claimed to be before 1947. She stared at the artifacts, feeling them tug at a part of her life she had never questioned.

She did not understand the letter, but she understood enough. This was the life before Harry Thompson. This was Hiroshi Tanaka. She kept the box. Years passed before she decided what to do with it. For a long time, it sat on a shelf in her home office, untouched, except for the occasional moment when she would lift the lid, look at the young soldier’s eyes, and wonder how two men, one in uniform, one in work boots, could live inside the same lifetime.

Eventually, as age soft the edges of her grief and sharpened her desire to honor the truth, she donated the box to the Camp Hood Historical Museum. She mailed it with steady hands and a note explaining only that it belonged to someone who had lived a quiet life nearby and who had wished perhaps for his silence to one day be understood.

It sits there now in a quiet corner of a small exhibit on P camps. Most visitors walk past without noticing. They come for the tanks, the barracks reconstruction, the photographs of young Americans training for a war that reshaped the world. But those who linger in that corner find a simple display, a wooden box, a sepia photograph, a letter whose translation is printed beside it, a faded map with pencil markings, and beside it all, a modest placard telling the story of Hiroshi Tanaka, the man who disappeared in 1943 and reappeared as

Harry Thompson. living proof that identity is not a fixed point, but a river that carves new channels through stone. The war produced millions of stories, most lost to time. Stories of men who rose and fell, who returned home changed or didn’t return at all. Some ended in triumph, others in tragedy. Tanaka’s ended in silence.

Not the silence of death, but the silence of transformation. It was a silence chosen, cultivated, lived in. He had crossed an ocean, fought a war, been captured, escaped a camp, and shed a name that no longer fit the shape of his life. He had lost his country, but found a different kind of belonging in the messed hills of Texas, where the sky was so wide it could swallow a lifetime.

He never returned to Japan, whether from fear, shame, or acceptance. Even his daughter never knew. He sought no recognition, wrote no letters, and let the man he’d been fade into the man he became. History remembers battles, not quiet men like Kanaka, who learned to men fences, coax soil to life, and leave footprints the wind erased.

His story is not escape, but arrival at a peace earned through silence and work. The Texas soil still holds him, more real than any legend.

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load