France, September 1944. The war had turned inside out. Only three months earlier, the fields of Normandy had been filled with German armor. Tigers and panthers prowling through hedge under banners that still promised victory. Now the same roads were littered with burnt metal and black smoke, pointing east like wreckage, trying to crawl home.

A small Vermached field maintenance unit trailed behind the retreating army, its trucks coughing fumes and its men running on exhaustion instead of fuel. Sergeant Carl Noman, 34 years old, was the unit’s chief mechanic, a man who had built engines before the war and spent the last 5 years trying to keep them alive. His convoy consisted of two Opal Blitz trucks, one halftrack with a broken starter, and 12 mechanics who carried more wrenches than bullets.

Their orders were simple and impossible. Recover any usable equipment left by retreating units and keep the roads clear for the remnants of the Seventh Army. But by early September, the roads were clogged with refugees, burning vehicles, and Allied aircraft that owned the skies. One afternoon outside the ruined town of Compenia, they spotted something strange.

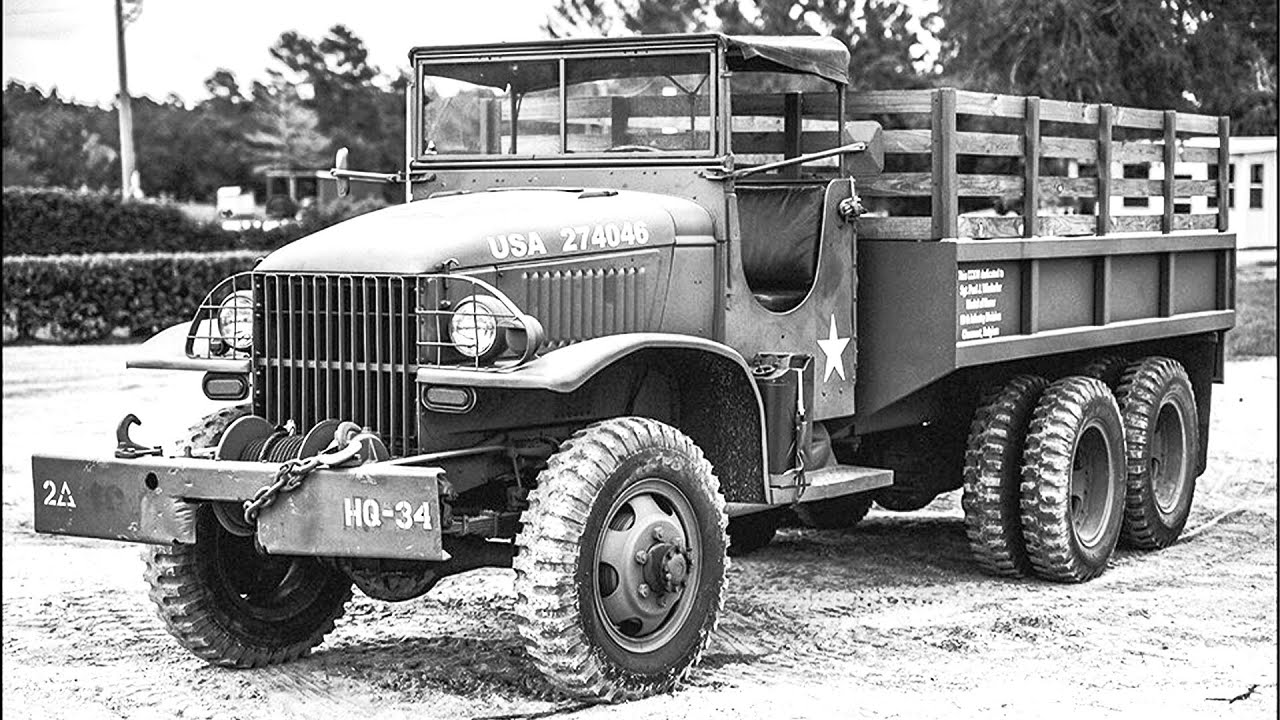

A large truck stood abandoned in a ditch, half hidden by smoke from a nearby barn. Its olive paint glimmered under layers of dust. The white star of the Allies barely visible beneath soot. The tires were intact. The engine looked unscathed. It wasn’t German. Noman ordered his men to approach cautiously, expecting mines or booby traps.

But when they circled the hood, they saw the logo embossed into the metal. GMC. They had heard rumors about these trucks, the Americans magic machines that could carry supplies over any terrain. The Vemar had captured Jeeps and the occasional Dodge before, but never one of these. The truck was enormous, far larger than any German transport.

It had a wide solid frame, massive suspension, and a cargo bed packed neatly with crates marked US Army, rations, spare parts. One of the younger mechanics, Otto, whistled. Her sergeant, this one could carry three opals inside it. Noman, climbed into the driver’s seat. Everything felt different. the smooth steering column, the precision of the gauges, the perfect tension in the pedals.

Even after months in the field, the cab smelled faintly of oil and leather, not diesel smoke and despair. He turned the ignition, and the engine roared to life instantly. No choke, no delay, no coughing. The men stared speechless. This, Noman muttered, was built by a country that doesn’t run out of steel. By evening, they had pulled the truck to the side of the road and started examining it piece by piece.

The engine was massive, a six-cylinder, 270 cubic in monster that could run on poor fuel, climb steep hills, and carry three tons without strain. The American engineers had designed it for one purpose: endurance. Otto ran his hands along the transmission housing and shook his head. This isn’t a truck.

It’s a factory on wheels. In the fading light, they opened one of the crates in the back. Inside were dozens of identical spare parts, hoses, filters, bearings, each wrapped in wax paper and labeled in English, ready to be swapped in minutes. For German vehicles, every repair required improvisation. For the Americans, it was mass production at a scale none of them could comprehend.

Noman stared at the mountain of replacement parts and understood something no propaganda could hide. Germany was fighting a nation that could build these trucks faster than the Vermacht could destroy them. He turned to his men and said quietly, “Boys, if they have a thousand of these, the war’s already lost.” They parked the big American truck beneath a shattered plane tree and set to work like surgeons.

Even in the failing light, the thing looked deliberate. Nothing rattled. Nothing sagged. Where German vehicles showed the scars of field repairs, wire twisted through bolt holes, odd-sized metric screws stolen from three different factories, the GMC looked as if it had rolled off the line an hour ago. Otto crawled under the nose and whistled again.

6×6 drive, he called, tapping the transfer case. Selector for low range and a front-mounted winch rated stronger than our halftracks. He slid out, palms black with clean grease. Clean. The Americans even made dirt look orderly. Newman pulled down a canvas pouch clipped behind the seat and found a laminated lubrication chart, a simple map of nipples and intervals readable by a farm boy.

Next to it, a thick manual stamped TM10-1563 with step-by-step drawings, torque values, parts numbers, exploded diagrams. You could hand this book to a baker and he’d service the truck by supper. Look, Otto said, prying open another crate. Inside lay oil filters in waxed cartons, a dozen fan belts marked with identical codes, bundles of spark plugs wrapped in oiled paper.

A canvas roll of tools matched the manual exactly. Every SAE wrench nested in its pocket, each size printed in bold. They build a problem, Otto murmured, then ship the solution with it. The cargo bed yielded more surprises. Green tins stamped US–10in1 rations stacked beside D-ration chocolate bars, cigarettes, instant coffee, and morphine cigarettes in a medic’s tin.

There were jerry cans, proper ones with wide mouths and rubber gaskets that didn’t leak, filled with gasoline, not the watery sats that chewed through German carburetors. A tarpolin bundle hid two spare tires with deep NDT tread still chalk striped from an American depot. Nuoman ran a thumb over a stencil on the tailboard. CKW352 2 and 1/2 ton.

He’d heard the nickname from prisoners taken near a ranches. Deuce and a half. The men said it with an affection you reserved for a friend. He could see why. Starter, he told Otto. The engine caught on the first twist. Inline six, smooth and even, like an electric motor pretending to be an engine. Noman listened.

No knocks, no coughing fits, a steady burble through a muffler that didn’t sound like a parade. He pulled the long gear lever and felt synchrome bite. No double clutch dance, no grinding teeth. The hydraulic brakes took the weight without drama. The truck settled as if it trusted its own stopping power. They rolled onto the empty road.

Headlights louvered to blackout slits. The big truck soaked up potholes that would crack an opal’s spine. A ruined culvert forced them into the ditch. Noman dropped to low range, engaged the front axle, and eased it out with the winch, worring, cable singing. the whole machine behaving like a patient ox that had no intention of quitting.

“A French farmer, cap in hand, stepped from a gate and pointed up the road.” “Leameó,” he said, drawing a long line with his arm. “Tut lanui all night convoys.” He rubbed his fingers together to show number beyond counting. Back by the plain tree, the men ate American biscuits like a sacrament and took inventory.

One crate held sealed ignition sets, points, condenser, rotor, bagged as a kit. Another brake cylinders identical, each in its own tin. A canvas satchel contained convoy placards, a chalkboard strip, and a stencil of a red circle with an arrow. Noman frowned, then understood. root markings. He’d heard the enemy’s black joke in the cafes of Chartra.

Red ball, the Americans rolling highway that ran without sleep from the ports to the front. He found the proof under the seat, a grease stained tag, penciled in English, red ball express, convoy B47, le a chartre shaong. Departure, halts, fuel points, check times. It read like a train timetable. Trains of trucks. He crouched on the running board and stared at the card until the numbers blurred.

Berlin had promised a rational war. Plans, timets, exactitude. This This was industrial rhythm turned into motion. A factory that never stopped on wheels. Klouse, the oldest mechanic, leaned his back to the tire and said what they were all thinking. We repair a panther with hand tools in the rain.

They replace an axle in 20 minutes and file a form. We nurse one tank for 3 days. They send 10 trucks an hour. The comparison spilled out of them. German engines were exquisite. Each factory its own little kingdom of tolerances, gears, and bolts that refused to match any other makers. A Maybach from Castle sulked if you fed it poor fuel.

Abusing last month refused a Bosch pump scavenged from an old chassis. Every vehicle was a personality. Every repair an argument. The American truck was standardization with a soul. Every hose fit. Every thread matched. Every part number led to a warehouse already emptied into another truck. They had built a machine that forgave mistakes and rewarded speed.

Paint out the star. One of the men suggested, “Half a joke, half survival. We keep it.” Noman looked up at the sky. The high growl of Jaros fighter bombers haunted every clear hour. Paint wouldn’t fool thunderbolts. A white star or a smeared cross, the silhouette would still read enemy, and an American convoy would be back for this truck by dawn, or a P47 would turn curiosity into shrapnel.

He climbed down from the cab and sat on the step, the big engine ticking as it cooled. “Listen,” he said, voice even. “We tow it east until dark. Strip what we can use and push the rest into the river. If it stays on this road, it will bring the enemy to us.” Otto hesitated. “Hair, Sergeant, this one truck, it could carry our whole section.” Noman nodded.

One truck won’t change a war. He held up the red ball card between two fingers. This is the war. Schedules, fuel points, thousands of these, nose totail, day and night, while we argue over a gasket. They fell silent, the kind of silence that comes when men stop lying to themselves. A month ago they had believed the talk of miracle weapons and counterstrokes.

Tonight a single captured truck had taught them more than a year of speeches. They worked by touch until midnight. Belts, filters, plugs, hoses, anything they could adapt to German engines went into a pile. The jerry cans they kept whole. Good gaskets were rarer than luck. The medical tin they divided without words.

Morphine was a currency that bought time from pain. Noman made them take the tool role too. Not for the sizes but for the habit. A place for every spanner, a number for every part. When the moon lifted, they winched the emptied GMC toward the culvert. It rolled like a dignitary. At the lip, Noman paused and put a palm on the fender.

You win, he said, not to the truck, but to the idea that had built it. They eased it over. Metal groaned. Water splashed. The big shape settled into reads and shadow. Now what? Klouse asked. Now, Noman said, folding the red ball card into his breast pocket. We stop pretending we can fix this war with a wrench. Dawn would bring orders, aircraft, and more roads pointing east.

But the men climbed into their ailing opals with a new unwelcome clarity. Somewhere beyond the horizon, an American dispatcher chalked B-48 on aboard and sent another river of trucks rolling. Germany, Noman realized, wasn’t being beaten by better tanks or braver men. It was being outs supplied on a scale no courage could repair.

Two nights later, they found themselves camped on the edge of a forest near Raz, waiting for orders that never came. The Vermach retreat had turned chaotic. Bridges blown too early, fuel convoys bombed, and columns tangled like veins clotted with wrecks. For Carl Noman’s maintenance detachment, there was nothing left to maintain.

Their last opal coughed itself to death outside a village where the church had lost its roof but not its bell. At dusk, Noman climbed a small ridge to scout the road. What he saw below didn’t look like a war. It looked like industry on the move. A line of American trucks, headlamps hooded but glowing faintly, rolled east at a steady pace, one every few seconds, the rhythm as precise as a machine press.

He counted 10, then 20, then stopped. There was no point. The convoy stretched beyond sight, their engines humming like an enormous heartbeat that never missed a beat. Every truck looked exactly like the one they had found. The same star, same cargo frames, same disciplined spacing. They bore placards painted with numbers and colored symbols. B48 R12 convoy A.

It was the Red Ball Express, the Allied lifeline feeding Patton’s Third Army. Over 6,000 trucks ran day and night, carrying ammunition, fuel, rations, and spare parts from the ports to the front. To Noman, it was like watching a myth come alive. He crouched behind a hedge, listening.

The road sang with a constant drone, not of chaos, but order. Every vehicle passed with the same even note, exhausts tuned, engines in harmony. The occasional jeep darted alongside, its driver waving a clipboard like a conductor correcting the tempo. They were not racing, not panicking. They were working. One of his men, Otto, whispered beside him, “They don’t even have guards.

They don’t need them,” Noman said quietly. “No one could stop them.” By morning, the road was empty again, but the smell of diesel and hot rubber lingered in the air, the scent of abundance. The Germans followed it north, hoping to rejoin retreating forces near the Ziggfrieded line, but every step along the way reinforced what they had seen.

Villages once stripped bare by years of German requisition now overflowed with Allied stockpiles, fuel drums stacked like walls, food crates marked rations, type K, and endless spare tires leaning against barns. Everywhere they looked, GMC’s, some loaded, some empty, were parked in perfect rows, engines idling as fresh crews swapped in.

Drivers looked barely older than boys, but they worked with practiced ease, unloading and moving on without shouting or confusion. Newman spoke enough English to understand the slang painted on some hoods. Memphis Bell Express, Kansas Mule, Detroit Rollers. He realized then that this wasn’t just a military operation.

It was a culture of logistics. America had weaponized motion itself. The contrast was unbearable. In German service, fuel was rationed by the liter, tires patched with canvas, and every broken axle meant another vehicle abandoned. Their engines coughed on airsat’s gasoline distilled from coal. Orders arrived late, maps were outdated, and the Luftwaffer no longer existed to cover them.

Even when Germany captured Allied trucks early in the war, it couldn’t keep them running. There was no compatible fuel, no standard parts, no time. But the Americans had everything and enough to waste. They reached an abandoned Luftvafa airirstrip where a handful of soldiers were dismantling radio equipment for scrap. The group’s officer, a gaunt Oberloidnant, looked up when Noman arrived and asked if they’d found any vehicles.

Noman hesitated, then told him about the captured GMC. The officer gave a weary laugh. Good. Maybe we can use it to tow our dreams home. He didn’t ask for it. Didn’t need to. He’d seen the same convoys himself. They bring fuel faster than we can burn it, he said, staring toward the western horizon.

They have turned the world into a road. Noman nodded. And we are running out of road. That night the sound returned, faint but steady. Another convoy miles away, invisible behind the hills, but unmistakable. It was as if the Americans had built a second front made entirely of engines and headlights. One of the younger mechanics, trying to sound hopeful, said, “Maybe the Furer has a countermeasure.

” Noman didn’t answer. He thought of the red ball card still folded in his breast pocket. the schedule, the precision, the orderliness of a country that treated logistics as seriously as artillery. He thought of the opal blitz they had once woripped as a workhorse, now a relic beside a machine that could run for a thousand miles without a hiccup.

And he thought of the irony that the Americans called their trucks by a simple name, deuce and a half. There was humility in it. Germany built weapons that demanded worship. Tigers, panthers, messes. America built tools that demanded use. And that, Noman realized, was why Germany would lose. Tools, not trophies, win wars.

The next morning, a British reconnaissance patrol rolled through the forest. Noman and his men didn’t fire. There was no point. They were unarmed, covered in oil and dust, their vehicles dead. The British officer who approached them seemed surprised they were mechanics, not infantry. “Working on anything interesting?” he asked in careful German.

Noman nodded toward the horizon where the rumble of engines still carried. “Yes,” he said. “Your trucks, they are working on us.” The officer smiled faintly, not understanding the full weight of the words, and motioned for the Germans to follow. Behind them, the road echoed again. Another convoy approaching, another river of machines that would not stop until the war itself did.

Noman didn’t look back. He didn’t need to. He had already seen Germany’s future, and it had GMC stamped on every part. The guns had gone silent, but the engines never stopped. Even in defeat, the rumble of Allied transport convoys rolled through the valleys of a broken Reich like an endless reminder of motion and of everything that Germany had run out of.

In a makeshift prisoner of war camp outside Mines, Sergeant Carl Noman sat at a wooden table surrounded by men who once believed they could fix anything. mechanics, drivers, depot clarks, the invisible backbone of a dying army. Their hands still bore the tattoos of grease and oil, but now they had nothing to repair except their thoughts.

The war they had lived through wasn’t the one the officers wrote about. It wasn’t grand maneuvers and glory. It was spare parts and shortages, improvised tools and missing bolts. It was rebuilding the same truck five times because there was no new one to replace it. And that Noman knew was where Germany had lost long before the bombs fell on Berlin.

Across the camp’s wire fence, Allied soldiers maintained their vehicles with quiet precision. Rows of GMC trucks, fresh, clean, gleaming with new paint, lined the field like a factory floor under open sky. Each morning, a detail of American mechanics in crisp coveralls serviced dozens in an hour.

Fluids checked, tires replaced, tanks refueled. The trucks purred to life and rolled off in perfect intervals. No man watched in silence, half admiration, half heartbreak. Every sound told him something about how the Americans had won. A hammer struck only once because bolts fit. Wrenches clicked in rhythm because threads matched.

Engines started without protest because fuel, oil, and parts all came from a single standardized world. On their side of the wire, the Germans scavenged wood to patch their shoes. One day, a young American sergeant approached the fence and tossed over a cigarette tin. Inside, neatly folded, was a maintenance pamphlet, an army motors bulletin showing diagrams of GMC brake systems.

No man studied it that night under candle light. Every number, every line, every note reflected a philosophy he’d never been taught. Make everything the same so everyone can repair it. When he translated the caption at the bottom, he almost laughed. It said, “Every man a mechanic, every mechanic a soldier.

” It was the opposite of the Reich’s creed. Germany had worshiped the master craftsman, the perfectionist who built machines too refined for mass war. America had trained its farmers and truck drivers to be engineers in uniform. They didn’t build for perfection. They built for replacement. A few weeks later, Allied officers arrived to question the German prisoners.

not about crimes or tactics, but about production capacity. The Americans were cataloging every captured factory, every rail line, every remaining engine. Newman was asked to help translate for a British logistics officer, a man named Captain Miller, who carried a clipboard thicker than a Bible. Miller showed him photographs of rows of American factories in Detroit.

Each building churning out hundreds of identical engines per day, assembly lines that never slept, powered by electricity, not ideology. He pointed to one picture and said, “That’s a week’s output for us.” Newman nodded, recognizing the shape of the GMC engine block he had once touched in the field. “A week?” he repeated softly.

That is more than we built in a month. Miller smiled. That’s why we never ran out of trucks. Noman asked almost out of habit how many the Americans had produced. Miller checked his notes. Just over half a million deuce and a halfs by this spring. Another quarter million dodges. About 60,000 jeeps a month at one point.

No man did the math in his head, then stopped. There was no point. Half a million trucks meant half a million supply lines, half a million arteries pumping fuel, food, and ammunition into a war Germany could never hope to match. It wasn’t the Sherman or the Mustang or the B17 that had crushed the Reich. It was the logistics that fed them all.

In August, rumors reached the camp of two new bombs dropped on Japan. weapons that ended the war overnight. But Noman didn’t need nuclear physics to understand inevitability. He had already seen the bomb that destroyed Germany. It just happened to have wheels. He often thought about the truck they had found near Compenia, how pristine it had looked, how alive.

He wondered if another German unit had found one, too, and felt the same sinking recognition. It didn’t matter. Even if they had captured a h 100red, the Americans had 10,000 more on the road that same day. One evening, as the sun fell behind the ruins, Otto asked him quietly. Do you think our machines were bad? Noman shook his head. No, they were too good.

Otto frowned. Too good? Yes. Too complex, too rare, too slow. We built masterpieces. They built momentum. He gestured towards the distant hum of engines beyond the camp. That sound you hear, that’s how they won. Not with genius, but with consistency. When the prisoners were released in 1946, Noman returned to a Germany that no longer believed in miracles.

The factories that had built tigers now made farm tractors. The railways that had carried Panza divisions now carried grain. But in every rebuilt workshop, one lesson endured. Efficiency beats artistry when survival is at stake. Years later, in a small repair shop in Hanover, Noman kept a relic on his workbench, a single Red Ball Express convoy tag, laminated and faded, rescued from the truck they had once found.

Whenever young apprentices asked about it, he would smile and say, “That’s the day I learned how wars are really won. Not by who shoots first, but by who can keep driving.” And outside his workshop, sometimes Americanmade trucks rumbled by on reconstruction duty, carrying supplies across the new roads of Europe.

The sound made him pause every time. The same low growl of engines that had once echoed through France, reminding him that the machine that had defeated Germany was not a tank or a bomber, but a truck built not for glory, but for endurance.

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load