Somewhere on the Baltic front, 1943, the crew of a German Panza saw a brief flash in the treeine 400 m away. Seconds later, the tank erupted in flames. In the minutes that followed, three German military tractors were destroyed the same way. Four armored vehicles, four catastrophic explosions, four shots. The Germans searched for anti-tank guns, heavy mortars, perhaps undetected landmines. No rifle could do that.

But the man who destroyed them had none of those things. He had only a standard Mosen the Gant rifle and four bullets that shouldn’t even exist. How is it possible that 7.62 62 rifle ammunition, the same that kills soldiers, could explode German tanks as if they were paper. To understand how Ivan Sidorenko could do this, you first need to understand the war he was fighting and why what he did was considered impossible by every military doctrine of the time.

By 1942, the Eastern Front had become the largest and deadliest theater of war in human history. Over 400 kilometers of frozen hell stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. The Vermachar had pushed deep into Soviet territory, and the Red Army was bleeding divisions faster than Moscow could replace them.

The German war machine seemed unstoppable. Their Panza divisions were the most feared armored units on Earth. A single Panza 3 tank required a direct hit from a 45 mm anti-tank gun to be stopped. The idea that a man with a rifle could destroy one was absurd. It violated the basic mathematics of warfare. The doctrine was clear.

Infantry kills infantry. Artillery kills fortifications. Tanks kill tanks. That was the hierarchy. A sniper’s job was to eliminate offices, machine gun crews, and communication personnel. Vehicle destruction belonged to specialized anti-tank units with weapons weighing hundreds of pounds. But on the Baltic front, in the forests of Estonia and Latvia, the rules were about to be broken by a man who understood something.

The generals didn’t. The environment wasn’t just terrain. It was a weapon. The Baltic forests were dense, primordial, and unforgiving. Visibility dropped to 50 m in some areas. Roads were narrow, muddy, and easily blocked. German armor designed for the open steps and French plains became trapped in kill zones where maneuverability meant nothing.

And in those forests, waiting in the frost and shadows, were men like Ivan Cedoreno. Men who had grown up hunting in these woods. Men who understood patience not as a virtue, but as a survival skill. And now, zoom in. pull the camera back from the maps and the generals and the grand strategy and focus on one man.

Ivan Mkhyovich Sidoreno, born September 12th, 1919 in the Glinkovski district of Smealinsk Oblast, a rural area where the closest thing to a city was a collection of wooden houses around a dirt road. He wasn’t a career soldier. He wasn’t from a military family. Before the war, Ivan was a hunter and a competitive marksman.

Not a sport shooter, a hunter. That distinction matters. Sport shooters fire at stationary targets under controlled conditions. Hunters fire at animals that don’t want to be seen, don’t want to be heard, and will vanish the moment they sense danger. Hunters learn to read the forest.

The way branches move in wind versus the way they move when something is pushing through them. The way snow compresses under weight. The way sunlight reflects off metal or glass. These weren’t military skills. They were farming skills, survival skills. But when the Vermacht invaded in June 1941, these farming skills became the foundation of something terrifying.

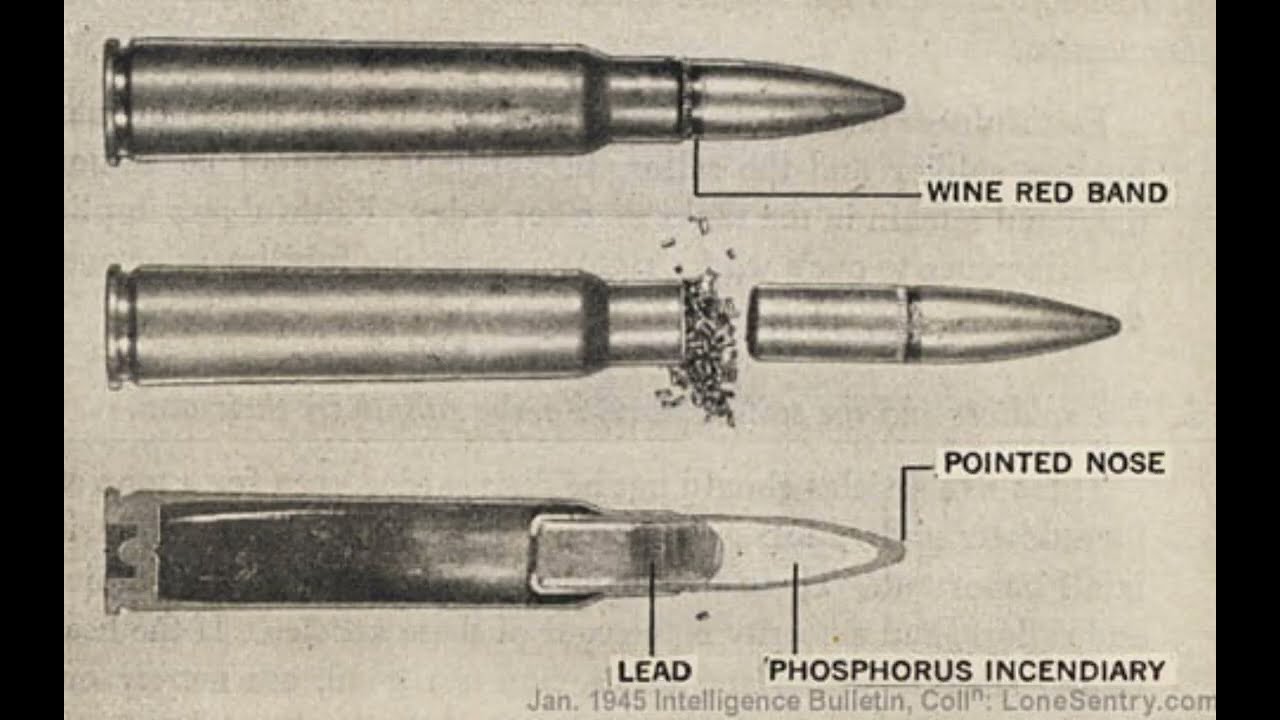

By 1942, Sidoreno had already been recognized as an exceptional sniper. His kill count was climbing into the hundreds. But what made him truly dangerous wasn’t just his accuracy. It was his understanding of a weapon that most Soviet snipers never even knew existed. The B32 incendurary armorpiercing round. Standard Soviet doctrine distributed these rounds in extremely limited quantities.

They were reserved for less than 1% of snipers, elite of the elite. Why? Because they weren’t designed to kill people. They were designed to kill vehicles. The B-32 round looked almost identical to standard 7.62x 54 mm R ammunition. Same brass casing, same size, but inside, instead of a solid lead core, was a small incendurary charge and a hardened steel penetrator.

When it struck metal, it didn’t just penetrate, it ignited. The charge was small, barely a few grams of incendurary compound, but it didn’t need to be large. It just needed to reach the right place. a fuel tank, an ammunition storage compartment, an engine block full of flammable fluids. But here’s the secret that separated Cidoreno from every other sniper who had access to these rounds.

He understood the anatomy of German vehicles. Most snipers saw Panza and thought armored target impossible to penetrate. Cidorenko saw a Panza and thought mobile fuel container with weak points. He had studied captured German vehicles during training rotations. He knew where the fuel tanks were located. He knew the thickness of the armor at different points.

He knew that the rear engine deck of a Panza 3 had ventilation grills that were only 15 millimeters thick. and he knew that if you put an incendury round through that grill at the right angle, it would detonate the fuel vapors inside the engine compartment. This was farmer logic applied to industrial warfare. A hunter doesn’t try to kill a bear by shooting it in the skull.

Too thick, too risky. A hunter shoots for the heart, the lungs, the arteries, the weak points. Cidorenko applied the same principle to steel. And on one particular mission on the Baltic front, he was given the opportunity to prove his theory under the most pressure-filled conditions imaginable. He was training an apprentice sniper, a young soldier who needed to learn not just how to shoot, but how to think.

And Cidurenko decided to teach him a lesson that would be recorded in Soviet military archives as one of the most technically perfect engagements of the war. Four targets, one Panza, three military tractors, four shots, four hits, four catastrophic kills, zero misses, 100% mechanical precision against moving armored targets.

But the real genius wasn’t the shooting. The shooting was just execution. The genius was the preparation. Cidorenko had positioned himself in a treeine overlooking a German supply route. He had ranged the road at multiple points using landmarks. He knew exactly how far away each position was. 400 m, 375 m, 425 m.

He had calculated the drop and wind drift for each position, and then he waited, not for minutes, for hours, motionless, watching the road through iron sights. When the German convoy appeared, he didn’t fire immediately. He waited until they were in the kill zone, until all four vehicles were exposed and vulnerable, and then he began the demonstration.

First shot, the Panza rear engine deck. The round punched through the grill and ignited the fuel vapors. The explosion was instantaneous. The crew didn’t even have time to react. Second shot, lead tractor, fuel tank. Same result. Third shot. Second tractor. Engine block. Fire spread to the cargo. Fourth shot. Rear tractor.

The driver tried to reverse. Too late. The vehicle erupted. Four shots. Four explosions. In less than 2 minutes, Cidorenko had destroyed an entire German supply convoy with a weapon that, according to every military manual, should not have been capable of doing what he just did. His apprentice stared in disbelief. Cidareno simply marked the kills in his log and began the retreat.

To him, it was just applied physics. Locate the weak point, calculate the trajectory, execute the shot. The same process he had used a thousand times hunting deer in the forests of Smealinsk, except now the deer were made of steel. But this wasn’t an isolated incident. This was Cidorenko’s routine, his daily work.

And as his kill count climbed from 100 to 200 to 300 confirmed kills, the psychological effect on German forces became impossible to ignore. German soldiers on the Eastern Front began reporting a phenomenon they couldn’t explain. Vehicles would explode without warning. Officers would drop dead from wounds that seemed to come from nowhere.

Machine gun nests would be silenced by invisible fire. And the reports all came from the same sector, the Baltic front. Wherever the 1122nd Rifle Regiment was operating, Soviet records from May 1st, 1943 contain a chilling entry in the regiment’s war diary. Captain Cidorenko, the regiment’s best sniper who killed 349 Germans, was nominated for hero of the Soviet Union.

The regiment’s distinguished snipers killed 15 fascists today. Of them, Cidorenko 4, Tishchenko 3, Mizoyan three. Four kills in a single day. Not remarkable for Cidoreno. That was a slow day. On other days, the number would climb to double digits. But it wasn’t just the quantity. It was the precision, the inevitability.

German soldiers captured by Soviet forces during interrogation described the terror of fighting in Cidoreno’s sector. They called it the hunting ground. Every movement felt watched. Every position felt exposed. They would hear a distant crack and someone would drop. No muzzle flash, no follow-up shot, just one crack and one death.

The psychological warfare was as effective as the physical kills. German units began refusing to advance into certain forest sectors. Morale collapsed. Officers stopped wearing rank insignia because Cidareno was known to target them specifically. But the true measure of Cidoreno’s effectiveness came when his existence became a problem not just for frontline commanders but for German high command.

Somewhere in the winter of 1943 a report landed on the desk of a vermarked intelligence officer. The report detailed an impossible anomaly. a single Soviet sniper operating in Estonia who had been confirmed responsible for over 300 German casualties. Worse, he was training other snipers. By December 1942, Soviet records show that Sidoreno had personally trained two apprentice snipers who had accounted for 71 additional kills.

By 1943, that number had grown. He wasn’t just killing Germans. He was creating a multiplication effect. Every sniper he trained would go on to train others. The German response was predictable. Kill him. But how do you kill a ghost? German counter sniper units were deployed to the Baltic front with one mission. Locate and eliminate Ivan Cidorenko.

These weren’t ordinary soldiers. They were sharutzen, the vermach’s elite marksmen, equipped with scoped mouser car 98k rifles and trained in the same hunting techniques Sidoreno used. But they made a critical mistake. They were hunting a man who had been hunting since childhood.

A man who understood that the hunter’s greatest advantage is patience. Cidorenko didn’t engage in sniper jewels. He didn’t take the bait. When German counter snipers moved into his sector, he would simply relocate. He operated on a rotation system, never staying in the same position for more than one engagement. He used decoys, false positions, and misdirection.

And when the German snipers finally thought they had located him, Sidoreno would be 500 m away, watching them through iron sights, waiting for them to expose themselves. Then one shot. The counter sniper unit would lose their best marksmen and the survivors would retreat. The reports back to German command were humiliating.

Target remains active. Counter sniper operations ineffective. The Germans escalated. If snipers couldn’t kill him, artillery would. Soviet records indicate that certain forest positions in Estonia were subjected to sustained artillery bombardment specifically to eliminate suspected sniper nests. Hundreds of shells would be fired into a single square kilometer of forest.

Trees would be shredded. The ground would be crated. And when the smoke cleared and German patrols moved in to confirm the kill, they would find nothing. Cidoreno had already moved hours earlier. The only evidence he had been there at all would be a carefully concealed spider hole now collapsed and a handful of spent 7.

62 mm casings. The Germans tried one final tactic. Overwhelming force. If they couldn’t outshoot him and couldn’t outweight him, they would simply remove the forest. Flamethrower units, incendurary shells, systematic destruction of tree cover. The strategy was desperate and costly. But it revealed something important.

The German high command was now dedicating significant resources to neutralizing a single man. That’s when Moscow took notice. By early 1944, Ivan Sidoreno had become a legend in the Red Army. His confirmed kill count had reached 500. He had trained over 250 snipers. He had survived eight wounds in combat.

He was, by every metric, one of the most effective soldiers the Soviet Union had ever produced. And that’s exactly why on June 4th, 1944, he received two pieces of news that would define the rest of his life. The first he was awarded the title hero of the Soviet Union, the highest military decoration the country could bestow.

The second he was being removed from combat permanently. The order came directly from high command and it was non-negotiable. Cidoreno protested. He wanted to continue fighting. He wanted to be on the front lines when the Red Army pushed into Germany. But Moscow’s logic was cold and mathematical. Cidorenko’s value as a sniper was significant, 500 confirmed kills.

But his value as a force multiplier was exponential. Every sniper he trained would kill dozens of Germans. Every sniper they trained would kill dozens more. The Soviet military had done the math. If Sidoreno died in combat, they would lose 500 future kills. If he survived and continued training snipers, he would be responsible for thousands of enemy casualties indirectly.

The decision was strategic. He was too valuable to lose. So they pulled him from the war. Not because he was broken, because he was too effective. The same year, 1944, Cidorenko was severely wounded in Estonia during one of his final combat operations. The injury was serious enough to hospitalize him for the remainder of the war.

By the time he recovered, Germany had surrendered. But here’s the question that haunts military historians. What was the real reason Moscow pulled him? Was it truly about preserving him as a trainer, or was it something else? Consider this. By 1944, the Soviet Union knew they were going to win the war. The question wasn’t if, it was when.

And as the Red Army pushed deeper into Europe, Stalin was already thinking about the post-war world, about propaganda, about heroes, about symbols. Dead heroes are useful, but living legends are powerful. Cidurenko wasn’t just a sniper. He was proof that a Soviet farmer could defeat German military technology.

He was a narrative. And Moscow needed that narrative alive. After the war, Ivan Cidoreno didn’t return to the forests of Smolinsk as a hunter. He remained in the military, training the next generation of Soviet snipers. He passed on everything he had learned. the weak points in armor, the psychology of patience, the discipline of the single shot.

He spent decades teaching young soldiers that warfare wasn’t about bravery. It was about preparation, about understanding your enemy better than they understand themselves, about using your environment as a weapon. He lived quietly in Dagasthan after his retirement. No interviews, no public appearances. When journalists asked him about his kills, about the secret ammunition, about how he destroyed a Panza with a rifle, his answers were always the same.

Simple, technical, no drama. I studied the vehicles. I found the weak points. I practiced until I could hit them reliably. There was no secret, just preparation. But there was a secret. The secret was that Ivan Cidoreno understood something that modern militaries are only now beginning to fully appreciate. Technology doesn’t win wars, people do.

The Panza was technologically superior to a Mosin Nagant rifle. The German military was better equipped, better funded, and better trained than a rural Soviet hunter. But none of that mattered when that hunter understood the machine better than the people operating it. When he had the patience to wait for the perfect shot, when he treated warfare not as combat, but as hunting.

The B-32 incendry round gave Cidorenko the tool, but his childhood in the forests of Smolinska gave him the skill and his understanding that war is just problem solving under lethal conditions gave him the mindset. That combination made him unkillable. Not because he was lucky, because he was prepared.

And when you combine preparation with opportunity, you get a farmer with a rifle destroying a panzer with four bullets. You get a man who killed 500 enemy soldiers and trained 250 more snipers. You get a soldier so effective that his own army had to pull him from the war because losing him would cost thousands of future kills. Ivanne Cidorenko died on February 19th, 1994 at the age of 74.

He never wrote a memoir. He never sought fame. He spent his final years in quiet retirement the same way he spent his youth watching, waiting, and understanding the world around him with a clarity that most people never achieve. But his legacy lives on in every military sniper training program that teaches patience over aggression.

In every soldier who learns to study their enemy before engaging. In every military doctrine that emphasizes intelligence over firepower. Because Ivan Cidareno proved something that generals hate to admit. Sometimes the most dangerous weapon on the battlefield isn’t the biggest gun. It’s the quietest man with the best understanding of how things work.

And when that man has four bullets that shouldn’t exist and the patience to use them perfectly, he doesn’t need an army. He becomes one. If you found this story as fascinating as we did, please hit the like button. Subscribe to the channel if you want to hear more forgotten stories from World War II. And we’d love to hear from you.

Leave a comment below telling us where you’re watching from and if you know of any other soldiers whose stories deserve to be told. Thank you for watching and thank you for keeping these stories

News

Iraqi Republican Guard Was Annihilated in 23 Minutes by the M1 Abrams’ Night Vision DT

February 26th, 1991, 400 p.m. local time. The Iraqi desert. The weather is not just bad. It is apocalyptic. A…

Inside Curtiss-Wright: How 180,000 Workers Built 142,000 Engines — Powered Every P-40 vs Japan DT

At 0612 a.m. on December 8th, 1941, William Mure stood in the center of Curtis Wright’s main production floor in…

The Weapon Japan Didn’t See Coming–America’s Floating Machine Shops Revived Carriers in Record Time DT

October 15th, 1944. A Japanese submarine commander raises his periscope through the crystal waters of Uli at what he sees…

The Kingdom at a Crossroads: Travis Kelce’s Emotional Exit Sparks Retirement Fears After Mahomes Injury Disaster DT

The atmosphere inside the Kansas City Chiefs’ locker room on the evening of December 14th wasn’t just quiet; it was…

Love Against All Odds: How Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Are Prioritizing Their Relationship After a Record-Breaking and Exhausting Year DT

In the whirlwind world of global superstardom and professional athletics, few stories have captivated the public imagination quite like the…

Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Swap the Spotlight for the Shop: Inside Their Surprising New Joint Business Venture in Kansas City DT

In the world of celebrity power couples, we often expect to see them on red carpets, at high-end restaurants, or…

End of content

No more pages to load