In the early months of 1942, American pilots in the Pacific were facing a nightmare they could not escape. The Japanese Mitsubishi A6M0 had become the most feared fighter plane in the world. It was faster, it was more agile, and it was killing American pilots at an alarming rate. The Zero could climb at over 3,000 ft per minute.

It could turn tighter than any American fighter. Its two 20 mm cannons and two 7.7 m machine guns could tear through an enemy plane in seconds. Japanese pilots had trained for years. They were aggressive. They were skilled and they believed they were invincible. The United States Navy’s primary carrier fighter at this time was the Grman F4F Wildcat.

On paper, it was inferior in almost every way. The Wildcat weighed between 2.5 to 3 tons. It had a maximum speed of only 318 mph. The Zero could reach 346 mph. In a turning fight, the Wildcat had no chance. The Zero could complete a full turn in just over 5 seconds. The Wildcat needed much longer. American pilots were dying at Wake Island, at the Marshall Islands, and across the Pacific.

The story was the same. Pilots who tried to dogfight the Zero rarely came back. Those who survived told stories of enemy fighters appearing from nowhere, turning inside them with ease, and filling their aircraft with bullets. But the Wildcat was not completely helpless. It had advantages that many overlooked.

The F4F4 model carried six 50 caliber machine guns with serious firepower. It had self-sealing fuel tanks that could survive multiple hits without exploding. Behind the pilot sat a thick plate of case hardened steel that could stop even 50 caliber bullets. The Zero had none of these protections.

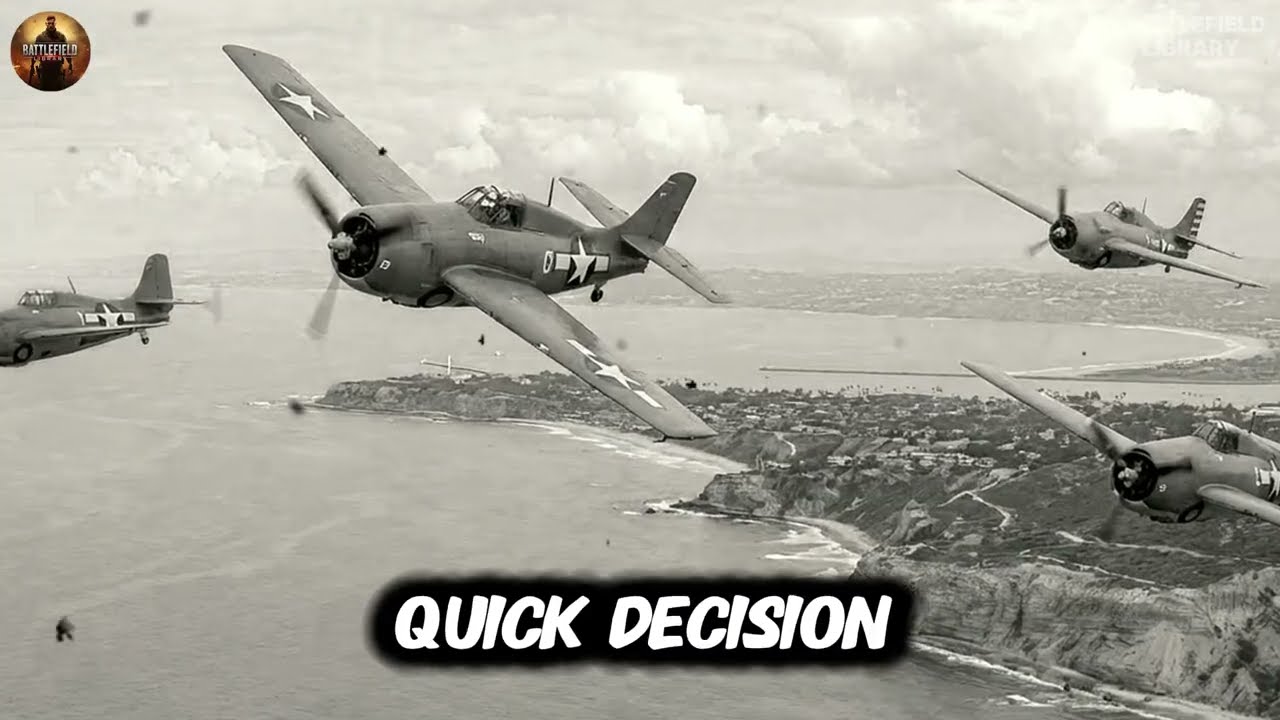

Its fuel tanks were simple vented boxes. One tracer round could turn it into a fireball. The problem was simple but deadly. American pilots could not survive long enough to use their advantages. They needed to hit the zero hard and fast. But how could they get into firing position against a plane that could outmaneuver them at every turn? In San Diego, California, one man was asking himself this exact question.

His name was Lieutenant Commander John Smith Thatch. He was 36 years old. He had been born in Pineluff, Arkansas. He had graduated from the Naval Academy in 1927, and he was about to change the history of aerial combat forever. Thatch was the commanding officer of Fighting Squadron 3, known as VF3. He was an expert in aerial gunnery.

He had spent years as a test pilot and instructor. He knew the Wildcat’s strengths and weaknesses better than anyone, and he had read the intelligence reports on the Zero with growing concern. The reports came from China, where the Zero had been devastating Chinese and American volunteer pilots since 1940. They described a fighter that seemed impossible.

Speed, range, climb rate, maneuverability. The Zero excelled in everything. Many American officers dismissed these reports as exaggeration. Thatch did not make that mistake. He understood a terrifying truth. If American pilots continued using traditional tactics, they would continue dying. The standard American formation was a three plane section, one leader and two wingmen flying in a Vshape.

This formation was too slow and clumsy against the nimble zero. When a zero got on your tail, your wingmen could not help you. You were alone, and alone against a zero meant death. Thatch needed something new, something revolutionary, something that would turn the wild cat’s weaknesses into strengths.

Night after night, he sat at his kitchen table in San Diego. His wife, Meline, would find him there late into the evening, deep in thought. In front of him were simple wooden matchsticks. He would arrange them on the table, move them around, and study the patterns they made. His fellow officers thought he was obsessing over nothing, but Thatch knew that somewhere in those matchsticks was the answer to saving American lives.

The breakthrough came after weeks of experimentation. Thatch had tried dozens of formations with his matchsticks. He had imagined countless scenarios. What if the zero attacks from above? What if it comes from behind? What if there are multiple attackers? Traditional wisdom said that when attacked, you should turn into your attacker. Force a head-on confrontation.

But against the zero, this was suicide. The Japanese fighter could simply turn inside you and end up on your tail again. No matter what you did, the zero always seemed to have the advantage. Then thatch had his revelation. What if he stopped thinking about individual planes? What if he thought about pairs working together? Two planes, not as leader and wingman in the traditional sense, but as equal partners, each one protecting the other.

He arranged his matchsticks in a new way. Two matchsticks side by side, separated by a distance equal to the wild cat’s turning radius. This was approximately 300 to 400 yd. He called this the beam defense position. The two planes would fly parallel to each other. Both pilots watching the sky and watching each other. Now came the crucial part.

What happens when a Zero attacks one of the planes? Thatch moved his matchsticks and found the answer. When an enemy fighter commits to attacking one Wildcat, both American planes immediately turn toward each other. They cross paths in the middle. The attacking zero, focused on its target, suddenly finds itself flying directly into the guns of the second wildcat.

Thatch stared at his kitchen table in amazement. It was so simple, so elegant, the Zero’s greatest strength, its ability to stay on a target’s tail, had become its greatest weakness. By committing to the attack, the Japanese pilot put himself in a trap. He could not see the second wildat coming until it was too late.

But would it work in the air? Matchsticks on a table were one thing. Real combat at 250 mph was something else entirely. Thatch needed to test his theory. He needed a pilot he could trust completely. He needed someone with quick reflexes, perfect timing, and absolute faith in the tactic. He found that pilot in a young enen named Edward Butch O’Hare.

O’Hare had just arrived at VF3, fresh from flight school. He was eager, talented, and hungry to learn. Thatch made O’Hare his wingman, and began teaching him everything he knew. The two men practiced the new maneuver again and again. They would fly side by side, then turn into each other at Thatch’s command, crossing paths with perfect precision.

The results exceeded Thatch’s expectations. Even when they simulated attacks with the throttle restricted to half power, making their Wildcats even slower than normal, the weaving maneuver frustrated every attack. Pilots playing the role of zeros could not line up a clean shot. They would commit to an attack and suddenly find themselves staring at the guns of the second Wildcat.

In early 1942, Thatch arranged a formal test. His four plane formation went into mock combat against another four planes, all wildcats. To make things harder, Thatch’s planes had their throttles restricted. They could only use half power. Normally, this would have made them easy targets. Instead, Thatch’s formation dominated the exercise.

The enemy pilots could not get a clean shot no matter how hard they tried. Word spread quickly through the Pacific Fleet. There was a new tactic. It might work against the zero. If you are enjoying this story, make sure you like and subscribe for more incredible true stories from history. The date was June 4th, 1942. The location was approximately 200 m northeast of Midway Island in the central Pacific Ocean.

The time was shortly after 900 a.m. Lieutenant Commander John Thatch sat in the cockpit of his F4F4 Wildcat on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown. The carrier was part of Task Force 17 under the command of Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher. Two other American carriers, USS Enterprise and USS Hornet, were operating nearby as Task Force 16.

American codereakers had discovered Japan’s plan to attack Midway Island. Admiral Chester Nimitz had positioned his carriers to ambush the Japanese fleet. Four Japanese aircraft carriers were approaching. The Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu. They were the pride of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The same carriers that had attacked Pearl Harbor 6 months earlier.

Thatch had a problem. His squadron had been devastated by transfers and reassignments. Before the Battle of the Coral Sea in May, he had loaned most of his experienced pilots to other squadrons. Now, as Midway approached, VF3 was rebuilt with a mix of veterans and rookies. Some of his new pilots had never seen combat.

Some had barely finished flight training. At approximately 8:38 a.m., Yorktown began launching her strike group. 12 TBD Devastator torpedo bombers from Torpedo Squadron 3 took off first, led by Lieutenant Commander Lance Massie, then 17 SBD Dauntless dive bombers, and finally Thatch’s fighters, only six Wildcats, six fighters to protect the entire strike group against the most powerful carrier force in the Pacific.

Thatch had hoped to take eight planes. He had trained his men in two four-plane divisions, but he was given only six. This created a problem. His beam defense maneuver worked best with four planes in two pairs. Six planes did not divide evenly. Thatch made a quick decision. He would fly with Enen Robert Ram Dib as his wingman.

Lieutenant Junior Grade Brainard Mccumber would lead the second section with Enen Edgar Basset. That left two extra pilots, machinist Tom Cheek and Enen Daniel Sheided. Thatch assigned them to fly behind the torpedo bombers as additional protection. There was another problem. Makumber was from a different squadron, VF-42. He had never trained in Thatch’s beam defense maneuver.

He did not know the technique that had spent months perfecting. In the chaos of preparing for battle, there was no time to teach him. The strike group formed up and headed northwest toward the Japanese fleet. The Devastators flew low, barely above the waves. The Wildcats flew higher at around 1,500 ft above the torpedo bombers.

The dive bombers were supposed to climb even higher and attack at the same time as the torpedoes. But in the confusion of launch, the groups became separated. At approximately 10:00 a.m., the American formation spotted the Japanese fleet. Four aircraft carriers surrounded by battleships, cruisers, and destroyers.

Black puffs of anti-aircraft fire began appearing in the sky, and then from above came the Zeros. The Japanese Combat Air Patrol spotted the incoming Americans. Between 15 and 20, Zeros dove down to intercept. They came like wolves attacking a flock of sheep. Their primary targets were the slow, vulnerable devastators, but they would have to go through that’s six wild cats first.

The moment of truth had arrived. Matchsticks on a kitchen table were about to face the deadliest fighters in the world. The first zero attack came from above and behind. It was perfectly executed. A Japanese pilot dove on the American formation with the sun at his back. His 20 millionth cannons opened fire. One of Thatch’s wild cats exploded into flames and fell toward the ocean.

The pilot never had a chance. Another Zero attacked almost simultaneously. This one targeted Thatch’s wingman, Ram Dib. The burst of fire did not hit Dib’s plane, but it destroyed his radio. Now Dib could hear commands, but could not respond. Communication in combat had just become extremely difficult. Thatch looked around and felt his heart sink.

One wild cat was already gone. Cheek and Sheidi had disappeared somewhere in the chaos. He could see only three American fighters, himself, Dib, and Mccumba. Three Wildcats against 15 to 20 Zeros. The torpedo bombers below were completely exposed. The Zeros swarmed around the Americans like angry hornets. They made slashing attacks from every direction.

Thatch tried to turn with them, but it was hopeless. The Zero could complete a turn in the time it took a Wildcat to start one. Then remembered his matchsticks. He remembered the countless hours at his kitchen table. He remembered the mock combats that had proven his theory. This was the moment everything had led to. Thatch keyed his radio and called to Dib.

He told the young Enson to execute the beam defense maneuver. Dib acknowledged. He slid out to the right, opening the distance between himself and Thatch. Approximately 300 yd now, separated them. They were flying parallel, just as Thatch had practiced so many times before. The Zeros saw what looked like an easy target, a single wildat flying alone, separated from his leader. They took the bait.

One zero locked onto Dib’s tail and began closing for the kill. Dib saw the zero coming. He did exactly what Thatch had taught him. He turned hard toward Thack. At the same instant Thatch turned toward Dib. The two wild cats crossed paths in the middle, their wings nearly touching. The zero pilot was committed.

He was focused on Dib. He did not see Thatch coming until it was too late. Suddenly, instead of shooting at Dib’s tail, he was flying directly across Thatch’s gunsite. Thatch pressed the trigger. 650 caliber machine guns roared to life. The Zer’s engine cowling shattered. Flames erupted from the fuselage.

The Japanese fighter rolled over and fell toward the sea. Thatch felt a surge of triumph. The matchstick maneuver had worked, but there was no time to celebrate. More zeros were attacking. He and Dib continued the weave, turning toward each other again and again. Each time a zero committed to an attack, the other wild cat was there to punish it.

Makumber watched and understood. Even without formal training, he could see what thatch and Dib were doing. He tried to follow their movements, staying close enough to help. A second zero made the same mistake as the first. It locked onto Dib during one of his turns. The Japanese pilot was too slow in his pull out.

He stayed on Dib’s tail a moment too long. Thatch’s guns caught him in a devastating burst. The Zero shed pieces of its cowling. Then its engine caught fire. Another kill. A third zero attacked. This time the pilot did not pursue Dib through the turn. Instead, he continued flying straight, trying to break away, but he had misjudged his speed.

Thatch’s guns were already firing. The burst caught the zero before it could escape. Three kills in a matter of minutes. Dib also scored. During one of the weaves, he spotted a zero converging on Thatch and Mccumber from behind. He turned into it and fired. The Zero fell away, trailing smoke. The weave was working against all odds, against a superior enemy.

Three Wildcats were holding their own. The battle continued for what seemed like hours, but was probably only minutes. Thatch kept weaving with dib. Zeros attacked again and again. Some broke off their attacks, frustrated by the strange American maneuver. Others pressed in and paid the price. But the wildats could not protect everyone.

Below the devastator torpedo bombers were being slaughtered. The slow, obsolete aircraft were easy targets for the Zeros. Lieutenant Commander Massie, the torpedo squadron commander, was shot down and killed. One by one, the Devastators fell from the sky. Of the 12 that had launched from Yorktown, only two would survive the attack.

Neither scored a hit on the Japanese carriers. Thatch watched the destruction with helpless fury. His fighters had done everything possible, but six Wildcats against 20 zeros could not cover an entire torpedo squadron. Then something extraordinary happened. At approximately 10:25 a.m., while the Zeros were occupied at low altitude, fighting the Wildcats and destroying the Devastators, American dive bombers arrived from high above.

Two squadrons of SBD Dauntless aircraft from Enterprise and Yorktown had finally found the Japanese fleet. The Zeros were out of position. They were too low, too focused on the torpedo attack to intercept the dive bombers. The Japanese combat air patrol, which should have been protecting the carriers at high altitude, was down at sea level.

The Dauntless dive bombers attacked unopposed. Within 5 minutes, three Japanese aircraft carriers were mortally wounded. Bombs smashed into the Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu. Fuel and ammunition stored on their decks exploded in massive fireballs. All three carriers would sink within hours. The fourth carrier, Hiru, survived long enough to launch a counterattack against Yorktown, but later that afternoon, American dive bombers found Hiru, too.

By nightfall, all four Japanese carriers were destroyed or sinking. The battle of Midway was over. Japan had lost the core of its carrier striking force. The tide of the Pacific War had turned. Thatch and his surviving pilots landed on the Yorktown. They were exhausted, their ammunition spent, their aircraft riddled with bullet holes, but they had survived.

And they had proven something incredible. The beam defense maneuver created with matchsticks on a kitchen table had worked in actual combat against the most feared fighter in the world. American pilots had found a way to fight back. After Midway Thatch was pulled from combat duty. The Navy decided he was too valuable to risk. He spent the rest of the war teaching other pilots his techniques.

The Thatch weave, as it came to be called, was adopted throughout the Navy and Marine Corps. It became standard doctrine for fighting the zero. Commander James Flattley, who had helped Thatch develop the tactic, was the one who gave it that name. Thatch himself had simply called it the beam defense position.

But thatch weave captured the imagination of pilots throughout the Pacific. Thatch rose through the ranks after the war. He became a rear admiral, then a vice admiral, and finally a full admiral. He developed new defensive tactics against kamicazi attacks. He served as commander and chief of United States Naval Forces Europe.

A missile frigot the USS Thatch was named in his honor. He died on April 15th, 1981 in Coronado, California, 4 days before his 76th birthday. He was buried at Fort Rose National Cemetery in San Diego, not far from where he had first practiced his revolutionary tactic. But his true legacy was not his rank or his medals. His legacy was the lives he saved.

Hundreds, perhaps thousands of American pilots survived encounters with zeros because of what John Thatch figured out with matchsticks on his kitchen table. He had faced an impossible problem. The enemy was faster, more maneuverable, and better trained. Traditional tactics meant certain death. So, he invented new tactics.

He turned the enemy’s strengths into weaknesses. He proved that courage combined with intelligence could overcome any obstacle. The next time you face a problem that seems impossible, remember John Thatch. Remember those matchsticks. Sometimes the greatest solutions come not from superior resources but from superior thinking. If you enjoyed this story, don’t forget to like and subscribe for more incredible true stories from

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load