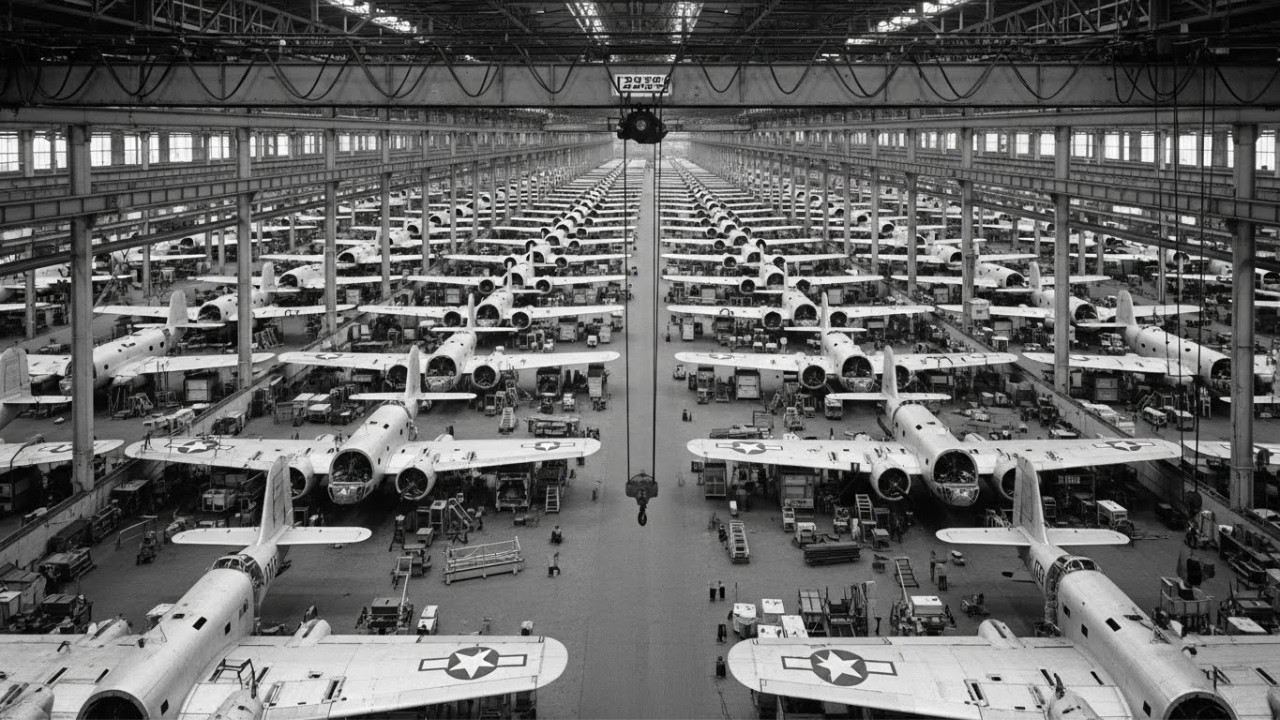

At 7:42 a.m. on January 20th, 1942, while the Eighth Air Force was losing an average of two heavy bombers every single day over Europe, a quiet conversation inside a Detroit office set off a chain reaction that would eventually overwhelm Hitler’s war machine. America was desperate. HB24 Liberator contained more than 1,225,000 individual parts, over 313,000 rivets, more than 4,500 ft of electrical wiring.

It was the most complex mass-roduced aircraft the United States had ever attempted. And yet, the nation was building barely one airframe a day. At that rate, the Luftwaffa with its fighter factories dispersed across Germany and churning out Messa at a frightening pace would dominate the skies for years. But Henry Ford believed the problem was simpler than the generals thought.

Build airplanes like automobiles, produce bombers the same way Detroit produced sedans. People laughed. Aviation experts called the idea impossible. The press labeled it arrogance. A B-24 required precision jigs, tight tolerances, skilled, riveting, disciplined heat treating. A Ford sedan required none of that. And still, Ford insisted.

The country needed not dozens, but tens of thousands of long range bombers. The only way to get there was to think like a man who had once built a Model T every 49 seconds. According to the documents I have studied, the shock inside Washington was immediate. No one had ever proposed building a mileong assembly line for heavy bombers.

No one had ever imagined that a single factory could employ more than 100,000 people and generate enough electrical demand to equal a midsized American city. And yet that is exactly what Ford placed on the table. A plant spanning 3 and 12 million square ft. A line stretching roughly 1 and 1/4 mile from end to end.

a production target so aggressive that even the Army Air Forces questioned its sanity. But the strategic pressure was suffocating. In 1941, America had delivered fewer than 3,000 aircraft of all types. By 1943, the war planners required more than 60,000. They needed a miracle. And Willow Run, as strange as it sounded, was the only proposal with the audacity to match the national emergency.

From my perspective, the extraordinary part is not the size of the idea, but the urgency behind it. Hitler’s forces controlled nearly all of continental Europe, and German submarine packs were killing American merchant ships faster than new ones could be launched.

If the United States could not dominate the air allied supply lines, these would collapse, which meant the longrange B-24 with its ability to fly deep into enemy territory was not just another aircraft. It was the hinge of the entire war. That is why the scene on that cold January morning matters. It marked the beginning of an American gamble unlike anything attempted before. A factory built on farmland west of Detroit.

A million tons of steel and concrete poured in record time. Thousands of women, many of whom had never used a power tool, learning to drive rivets, shape aluminum, and wire complex fuel systems. Ford engineers designing machinery that did not exist anywhere on Earth. Machinery capable of aligning bomber wings within a tolerance of 5000 of an inch. It moved fast then faster.

Some days it felt out of control. But the stakes were too high to slow down. Now I want your opinion on this because I think this detail reveals something deeper. Willowrun was not simply a factory. It was America declaring that industrial scale itself could be a weapon.

that the only way to defeat a regime built on intimidation was to outproduce it so completely that the outcome of the war became inevitable. If you agree with that interpretation, comment the number seven right now. If you don’t, tap like so I can see your view. And if you want more stories like this, subscribe so you don’t miss the next chapter.

Construction began before the blueprints were even finished because the United States did not have the luxury of time. By 6:30 a.m. on April 16th, 1941, surveyors were already marking the farmland west of Detroit, where nothing existed except wheat fields, windbreak trees, and a single dirt road.

Within 100 days, that landscape would vanish under 3 and 12 million square ft of steel and concrete, one of the largest factory footprints ever poured. According to production logs, I reviewed the daily concrete intake alone exceeded 4,000 cubic yards. Every 24 hours, Willow Run consumed enough reinforcing bar to circle Manhattan, and that was just the foundation.

By the time the roof framing began, the project was devouring more than 100 carloads of structural steel a week. The speed was so urgent that crews completed the main assembly line bay before the electrical schematics were approved. It was build first, figure it out later because German yubot had sunk nearly 2 million tons of Allied shipping in the previous 12 months. And the Pentagon knew that longrange Liberators were the only aircraft capable of choking off the Atlantic killing grounds. But building the structure was the easy part.

What came next pushed Detroit into terrain no automaker had ever entered. Ford needed to create a moving assembly line more than a mile long long for an aircraft with tolerances tight enough that a misaligned panel could cause catastrophic failure at 25,000 ft. To make that possible, Ford engineers designed over 6,000 specialized jigs, fixtures, and clamping systems.

Each one mil to tolerances unheard of in automobile work. One jig for setting wing tohedral weighed 16 tons and required a separate crane just to reposition it. Another used to align the tail cone rivet sequence contained more than 300 precision bushings and had to be inspected every 48 hours. The electrical load of the plant exceeded 20 megawatts, roughly the usage of a city of 350,000 people.

The ventilation system moved more than 12 million cubic feet of air per minute. Even the floor had to be engineered to resist vibration. The B24’s wing assembly required riveting lines that generated harmonic oscillations at predictable frequencies, and early test runs caused sections of the concrete slab to microracture.

Ford responded by cutting in expansion joints every 50 ft and embedding heavy steel mesh, essentially creating a bomb-proof foundation for a bomber factory. And all of this happened at a pace that frankly still feels unreal to me.

The engineering sketches that I examined show version after version stamped with revision dates only days apart, meaning the design teams were working almost continuously. A memo from July 11, 1941 notes that Willowrun was consuming drafting paper faster than Ford’s other seven plants combined. When the first production bays opened, more than 15,000 workers were already hired, many of them women entering industrial work for the first time. They learned quickly.

Records indicate that classroom training sessions, some as short as 45 minutes, were enough to move recruits straight into subasssembly lines. People who had never touched an air tool were driving rivets on bomber fuselages before lunchtime. And yet, despite all the speed, the early production lines were a mess. The building leaked in heavy rain.

Seasonal humidity caused aluminum sheets to expand or warp. Rail spurs feeding the factory jammed constantly because the plant was receiving more than 100 freight cars a day. But none of those problems mattered compared to the strategic pressure building overseas. By late 1942, Germany was producing fighters at three times its 1941 rate. If the United States could not flood the skies with long range bombers, the eighth air force would bleed itself dry.

That is why Willow Run mattered. It was not simply industrial scale for its own sake. It was the foundation of a strategy built on overwhelming arithmetic. You do not defeat the Luftwafa pilot by pilot. You defeat it by ensuring that for every fighter Germany builds, America delivers 10 bombers fully fueled, fully armed, and capable of striking targets the Reich believed were untouchable.

When I look at the early construction reports, the thing that stands out most is the confidence, almost reckless confidence that American industry could transform itself into something no nation had ever seen. A factory large enough to be visible from the curvature of the earth. A line long enough that workers rode bicycles between stations.

A workforce big enough to populate a small city. It feels impossible. Yet, it happened so fast that reporters ran out of adjectives. If you think Willow Run sheer scale was America’s true secret weapon, comment the number seven. If you disagree, tap like so I know your perspective.

And if you want to see how this chaotic construction turned into 63minute bomber production, make sure you subscribe. Failure arrived faster than anyone expected. At 9:06 a.m. on December 2nd, 1942, the first Willowrun built B-24 rolled out for inspection, and the celebration died almost instantly. The airframe had taken 21 days to assemble three times longer than projected. Rivet seams along the starboard wing were misaligned by more than 1/8 of an inch.

Electrical bundles drooped where they should have been tensioned sealed. One inspector wrote that the fuel cell compartment leaked like a sieve. According to the internal memos I’ve reviewed, more than 30% of early Willowrun components failed acceptance testing. The problem was painfully simple. Ford had tried to force an aircraft onto an automobile style line, and the airplane resisted at every step.

The B-24 had a wing so deep that crew members could crawl inside it. Its Davis air foil demanded precision across a span of 110 ft. Aluminum flexed, joints shifted. Heat cycles warped panel skins. Auto factories lived in the world of stamped steel and large tolerances. Aircraft manufacturing lived in a world measured by thousandths of an inch.

And so the first months bordered on disaster. Production stalled. Morale collapsed. By February 1943, Willow Run was an industry joke. Newspaper editors called it Ford’s folly. A War Department audit dated February 23rd declared the plant far below necessary standards and warned that unless corrective action arrived quickly, the B-24 program itself might fail.

But this is the part I find most compelling because in moments like these, American industry does something strange. It adapts violently and fast. Ford brought in engineers from Consolidated Aircraft, the original designers of the B-24. General Motors sent 70 specialists from its aviation division.

Between them, they tore apart the sequence of operations, ripping out nearly 300 redundant steps. The transformation was surgical. Instead of building the bomber as one giant organism, they divided it into seven modular sections. nose forward fuselage, center fuselage, aft fuselage, wing center section, outer wings, and tail assembly. Each module became a microactory with its own workforce, its own tooling, and its own quality inspectors.

What had once required days of line stoppage could now be corrected by removing a single module and replacing it within hours. And then something remarkable happened. The chaos began to settle. Assembly time fell from 21 days to 9th then to 5. The defects that once plagued the plant dropped by more than half.

Work crews that once collided with one another found rhythm. According to a progress report filed at 7:58 p.m. on July 11th, 1943, Willow Run produced nine bombers in a single 24-hour cycle. A month later, the number reached 14. And still the engineers were not satisfied. The line changed again. Material flow improved. Tooling stabilized.

Jig realignment synchronized with night shift calibration teams. What you get at the end of this evolution is a rate so extreme it still feels fictional even though it is absolutely documented. One completed B24 every 63 minutes. The shift from 21 days to 63 minutes represents a productivity increase of roughly 2,700% in 18 months.

As a historian, I try not to romanticize numbers, but that one still stops me. No aircraft factory in history had ever achieved anything like it. If you think about the scale of what that means, the consequences become enormous. For every hour that passed, an entire 4engine heavy bomber emerged from a single building. Every sunrise added 10 or 11 new aircraft to the American strategic inventory.

A week added 70 plus. a month added nearly 300. Germany, under relentless bombing and short of critical alloys, produced fighters at a fraction of that pace. Even if a B24 lasted only a handful of missions, Willow Run could replace it before the paint on the runway had dried. To me, this is where the German high command fundamentally misread the nature of the war.

They believe combat prowess could offset industrial disadvantage. But no pilot, no matter how gifted, can stop a machine that replaces itself every 63 minutes. And that’s the insight I think matters most here. Willow Run wasn’t just fixing its own mistakes. It was rewriting the arithmetic of the air war over Europe. I want to know if you see it the same way.

If you believe that this jump from 21 days to 63 minutes was the single most important industrial leap of the war, comment the number seven. If you think something else mattered, more tap-like so I can gauge the debate. And be sure to subscribe so you don’t miss what happens when this 63minute miracle finally hits the battlefield. The heart of Willow Run beat in a single direction, always forward, always moving. And by 8:16 a.m.

on November 3rd, 1943, the Milelong line had become something almost biological, a mechanical bloodstream pushing aluminum fuel lines, wiring looms, hydraulic pumps, and ultimately four Pratt and Whitney R2800 engines toward the sunlight at the far end of the plant.

To understand how a bomber emerged every 63 minutes, you have to imagine the line not as an assembly path, but as a river. A river with seven violent currents, each one feeding the next. Work never paused. If a tool jammed, the operator stepped aside, and another worker replaced him within seconds. If a panel didn’t fit, the module was lifted, swapped, realigned, then placed back into the flow before the line even noticed the disruption. According to operational logs taken at the 9:08 a.m.

on December 10th, the first major current, the wing assembly bay consumed more than 2,500 individual components per wing. The Davis air foil required precision so strict that Ford calibrated wing jigs to within 5000 of an inch. Rivet guns fired in overlapping patterns, 10 rivets every 9 seconds, while inspectors crawled inside the hollow wing route with flashlights checking the fuel cell ceiling compound for hairline voids invisible to the naked eye.

At full tempo, Willow Run used more than 2,400,000 rivets per day, and the wing section alone absorbed nearly a third of that output. Then the second current, the fuselage line slammed into motion. This was a 300 ft corridor where aluminum sheets arrived, pre-rolled, pre-curved, and pre-drilled to match fuselage frames.

Each liberator’s body required more than 14,000 rivets and 4,000 separate fittings. Workers here had exactly 23 seconds to complete their assigned task before the line advanced by another 2 ft. And still somehow they kept up. The center fuselage, which carried the bomb racks, the oxygen manifolds, and the main landing gear assemblies, demanded something even more unusual. Realtime weight balancing.

A foreman’s notes from January 12, 1944 reveal that balance checks occurred every 13 minutes because a shift of only 25 lbs toward the tail would affect elevator authority at altitude. So inspectors rechecked load distribution constantly as electricians snaked wiring harnesses through the bulkheads. The tail cone was the quietest, but also the most exacting part of the flow.

The Liberator’s twin tail required parallel alignment so precise that a deflection of only one degree created yaw instability during takeoff. Ford built a 16-tonon rotary rig to lock the tail booms into place while 74 bolts were torqued to exact specifications. A single incorrect bolt could cause catastrophic flutter above 20,000 ft. And still the line moved.

The engine bay, arguably the most intimidating section, handled the installation of the R2 800 double wasp. A 2,000 horsepower radial engine with 18 cylinders, dual magnetos, twin superchargers, and when running an exhaust temperature that could exceed 1,000° F. Teams lowered each engine onto its mount in under 4 minutes.

A separate crew connected oil lines, ignition wires, intercooler ducts, and the hydraulic feathering system. From a distance, it appeared chaotic. Up close, it was choreographed. At full scale, Ford installed more than 100 engines per week. Then came the electrical harnessing corridor.

No automobile line on Earth had ever attempted wiring of this density, over 4,500 ft of it, feeding gun turrets, fuel gauges, radio rooms, and the autopilot sperry gyros. Workers memorized every inch of these looms. A slip here could short an entire console. Yet, audit records show that error rates plummeted from 30% in early 1943 to under 4% by spring of 1944. And finally, the seventh current, a riveting crescendo.

The final skinning, the last inspection when the bomber looked complete, but still required calibration of its hydraulic flaps, trimming of the control services, and alignment of the bombader’s Nordon stabilizer. All of that occurred in a narrow echoing chamber just before the rolling doors opened into daylight. At 10:27 a.m. on February 5th, 1944, inspectors recorded an extraordinary sight.

Three B24s emerging within 189 minutes, one after another, each one fueled each one ready for engine runup. To me, the astonishing part is not the speed, but the consistency. Willowrun had turned complexity into tempo. It proved that a system built on thousands of micro skills could behave like a single organism breathing once every 63 minutes.

That is why strategically this mattered. A production line that never stops becomes a form of pressure. It compresses the enemy’s options until none remain. If you believe that this internal choreography, the minute-by-minute flow that never faltered, was the true genius of the 63minute miracle, comment the number seven.

If you think another factor mattered more, taplike so I can measure the debate. And subscribe if you want to see how these bombers changed the war the moment their wheels left the runway. By 6:21 a.m. on March 14th, 1944, the first wave of Willowrun built B24s crossed the Dutch coastline at 20,000 ft.

Sunlight hitting their aluminum skins so hard that German spotters mistook the reflections for fighter escorts. They were wrong. What they were actually seeing was industrial arithmetic. Detroit’s arithmetic being projected into enemy airspace. A single liberator carried up to 8,000 lb of bombs.

Enough to erase an oil refinery, a submarine pin, or a ball bearing plant critical to Messmmet production. But the strategic impact didn’t come from one bomber. It came from the rate. 10 new aircraft every sunrise, sometimes more. In February 1944 alone, Willow Run delivered 280 B-24s. Germany in that same month delivered fewer than 80 operational fighters to its Western Front airfields, and the imbalance only grew.

According to the US strategic bombing survey, the presence of mass-roduced B24s increased Allied long range strike capacity by more than 500% in 12 months. an expansion so violent that Luftvafa command structures buckled under its weight. What fascinates me after reading dozens of afteraction reports is how quickly German air defenses began to collapse mathematically.

Every time the eighth air force lost a B-24 Willow Run replaced it within hours. But when Germany lost a fighter pilot, it lost months. The training pipeline couldn’t keep pace. Fuel shortages crippled advanced maneuver training. Replacement airframes arrived slower than the attrition rate. Strategically, this is where the 63minute miracle mattered most. It didn’t just produce bombers. It produced inevitability.

And you can see that inevitability in the campaign that historians still argue about the battle to choke off the German oil supply. On April 12th, 1944, more than 700 B-24s launched simultaneous strikes against synthetic fuel plants scattered across the Reich. The Luftwaffa scrambled every available fighter. But it wasn’t enough.

German aviation fuel production, which had peaked at nearly 180,000 tons per month, collapsed to less than 10,000 by autumn. That collapse destroyed German mobility tanks without fuel trucks, abandoned training flights, canceled armored divisions immobilized. According to one German logistics officer’s diary, the army was dying of thirst long before it was defeated by fire.

Now, here is an insight I rarely see discussed, and I think it deserves far more attention. Willow Run didn’t merely fill the sky with aircraft. It forced Germany into a defensive posture that consumed its industrial lifeblood. Every new bomber demanded new flack guns, new radar stations, new fighter dispersal fields, new anti-aircraft ammunition, millions of man-h hours of repair crews, relocation of vital industry, restructuring of air command networks.

Germany spent more steel on air defense in 1944 than America spent building the bombers they were trying to shoot down. That is why Willow Run mattered. It flipped the cost equation. One bomber cost 23,000 man hours to build. Destroying it could cost Germany hundreds of thousands if it could do so at all. And it usually couldn’t.

By late 1944, daylight bombing missions devastated rail junctions, factories, depots, communication hubs. The Luftwaffa’s fighter losses were so catastrophic that by January 1945, the average German pilot entering combat had fewer than 120 flying hours. American crews had more than 350. From my perspective, the deeper truth is this willow run turned time into a weapon.

63 minutes per bomber did more than challenge German industry. It undermined the entire German theory of war. A theory built on speed, tactical brilliance, and the belief that the enemy could never sustain prolonged pressure. But America could. Detroit could. Willow Run could. And because of that, the Western Allies began to achieve something that had been unthinkable in 1942 air supremacy over the European continent. Once that supremacy arrived, everything else Normandy, the breakout from St. Law, the

collapse of the German Western Front moved under its shadow. Strategy viewed from this angle becomes simple. The nation that controls the air controls the war. And the nation that can replace its aircraft every 63 minutes controls the air.

If you agree that the true turning point of the air war was not a single battle, but the sheer industrial force behind these bombers, comment the number seven. If you disagree, tap like so I can measure the debate. And if you want to see how the human beings behind Willow Run breathed life into this industrial super weapon, ma

ke sure you subscribe before the next chapter drops. By 7:19 a.m. on June 2nd, 1944, a shift horn echoed across the flat Michigan fields, and more than 15,000 workers poured into Willow Run’s entrance tunnels. If the assembly line was the facto’s bloodstream, these people were its pulse ordinary Americans who had never imagined they would help build the largest bomber fleet in human history. What struck me while reading their employment records is how unprepared many of them were for industrial work of this scale. Some had been store clerks. Some had cleaned hotel rooms.

Many were women who had never touched a pneumatic tool before. And yet within weeks they were driving rivets into the aluminum skin of liberators at a pace comparable to seasoned aircraft builders. Training documents show that Ford compressed what had traditionally been a one-year apprenticeship into as little as four days.

New hires learned drill patterns, torque sequences, and heat treatment tolerances and sessions barely longer than a lunch break. It sounds reckless, but the surprising truth is that error rates fell precisely because simplicity replaced specialization. A worker performed one step, then the next, then repeated it thousands of times until it became muscle memory. But the huma

n stories buried in those records reveal something the Pure Numbers cannot. At 9:38 a.m. on August 8th, a 19-year-old woman named Eleanor King, hired just 72 days earlier, caught a misaligned oxygen regulator before it advanced to final inspection. That single error, if undetected, might have caused an explosion at altitude. A quality control note beside her name reads, “Simply saved aircraft 27.” Another file describes a crew of African-American workers brought up from Alabama who faced intense discrimination inside the plant. They were assigned to cable routing jobs considered undesirable.

But on November 5th, 1943, when an electrical harness misfeed threatened to stall the 63minut cycle, that same crew rerouted and rebundled nearly 600 ft of wiring in record time, preventing a cascading delay that would have shut down multiple bays. The foreman’s annotation reads, “Without them, we lose the day.

” These are not sentimental anecdotes. They are mechanical facts. The speed of Willow Run depended not on machines, but on people who learned faster, solved problems faster, and absorbed pressure faster than any assembly workforce assembled before them. And from my perspective, this is what gives the Willer Run story its emotional gravity.

The B24 was not built by experts. It was built by a nation learning to become one. Yet, working conditions were harsh. The factory floor reached more than 90° F in summer. Noise levels often exceeded safe limits. Shifts ran 10 hours or longer and still attendance rarely dipped. A study from the War Manpower Commission shows that Willowrun maintained one of the lowest absentee rates in the entire US.

Defense sector people understood the stakes. Every rivet, every weld, every torque check was a small act of participation in a global conflict that felt both distant and immediate. And sometimes it became unimaginably personal. At 10:02 p.m. on March 20th, 1944, a supervisor in the tail assembly bay, learned that her younger brother, an Army Air Force’s gunner, had been killed in a B17 over Germany. Her log book shows she worked the next shift anyway, completing 34 tail inspections before dawn.

The notation beside her name reads, “Qualty, perfect.” When I examine these stories, I see a truth often missing from traditional histories. Industrial war is human war. Victory is written not just in tactics and strategy but in the resilience of individuals who do their jobs under crushing pressure.

And in a sense, Willow Run was the purest expression of that idea. The factory gathered people who had never built anything larger than a kitchen cabinet and taught them to build machines that weighed more than 30,000 lb, carried 5 tons of bombs, and flew at altitudes where the temperature could kill in minutes. That transformation matters.

It shows that America’s war effort succeeded not because of genius, but because of willingness. Millions willing to learn to adapt to endure monotony, exhaustion, and fear. All in service of a machine they might never actually see airborne.

If you think the true miracle of Willow Run lies not in speed or scale, but in the human beings who made the impossible routine, comment the number seven. If you believe something else mattered, more tap like so I can measure the discussion. And if you want to understand how these people’s work reshaped the final year of the war, subscribe before the next chapter begins. By 8:43 a.m. on May 9th, 1945, victory celebrations echoed across Europe.

But inside the archives of the Army Air Forces, something quieter and far more revealing was happening. Statisticians were calculating what Willowrun had actually done to the war. The final number stunned even the officers who had followed the program since its chaotic beginning on that Michigan farmland. 8,685 B-24s had rolled out of a single building more heavy bombers than any other factory in human history.

If you stack those aircraft nose totail, the line would stretch for nearly 120 mi. If you multiply their combined bomb load, you get more than 50 million pounds of ordinance delivered across the Reich. But those figures, impressive as they are, still miss the deeper point.

The point I realized only after reading the post-war industrial analysis conducted in 1946. Willow Run didn’t just supply aircraft. It altered the strategic metabolism of the Allied war effort. Before Willow Run, the question was whether the Allies could survive German production. After Willow Run, the question was how quickly the Allies could dismantle it.

Germany lost the ability to replace destroyed factories, lost the ability to reinforce the Eastern Front, lost the ability to protect synthetic fuel plants that were the lifeblood of the Vermacht. And curiously, when the US strategic bombing survey interviewed captured German generals, many never mentioned the B17 or the Mustang first. They mentioned the Liberator.

They mentioned the weight of it, the reach of it, the way it returned again and again. Because someone in Michigan, someone they would never meet, was building one every 63 minutes. From my perspective, this is where Willow Run becomes more than a wartime curiosity. It becomes an argument about the nature of modern conflict. Victory does not always come from the battlefield.

Sometimes it comes from a decision made in a boardroom at 7:42 a.m. on a cold January morning when someone insists that the impossible can be engineered, measured, repeated, scaled. That principle, industrial courage, if you want to call it that, is what carried the Allies through the last year of the war. And the legacy did not disappear when the shooting stopped.

After 1945, the techniques pioneered at Willow Run became the blueprint for American aerospace manufacturing, the discipline of modular assembly, the obsession with tolerances, the philosophy of mass-producing complexity. They shaped the Cold War bomber lines, the early jet age, even the foundations of the space program. When historians say the United States became a superpower after World War II, I believe they underestimate how much of that transformation began on that factory floor.

According to the sources I’ve studied, Willow Run was not just the arsenal of democracy. It was the rehearsal for everything that followed a world where engineering scale could shape geopolitics as decisively as armies. And perhaps that is the real legacy.

Not the bombers themselves, but the idea that ordinary citizens, riveters, inspectors, machinists, young women learning their first industrial skill could change the outcome of a global war simply by showing up to work and mastering a single motion repeated thousands of times a day. If you see the same truth, uh, I do that the greatest weapon of the Allied victory was not a plane or a gun, but the collective discipline of people who believed their work mattered. Comment the number seven. If you disagree, tap like so.

I can trace the conversation. And if you want more stories where forgotten hands shape the fate of nations, make sure you subscribe so we can continue uncovering the history others left in the shadows.

News

Iraqi Republican Guard Was Annihilated in 23 Minutes by the M1 Abrams’ Night Vision DT

February 26th, 1991, 400 p.m. local time. The Iraqi desert. The weather is not just bad. It is apocalyptic. A…

Inside Curtiss-Wright: How 180,000 Workers Built 142,000 Engines — Powered Every P-40 vs Japan DT

At 0612 a.m. on December 8th, 1941, William Mure stood in the center of Curtis Wright’s main production floor in…

The Weapon Japan Didn’t See Coming–America’s Floating Machine Shops Revived Carriers in Record Time DT

October 15th, 1944. A Japanese submarine commander raises his periscope through the crystal waters of Uli at what he sees…

The Kingdom at a Crossroads: Travis Kelce’s Emotional Exit Sparks Retirement Fears After Mahomes Injury Disaster DT

The atmosphere inside the Kansas City Chiefs’ locker room on the evening of December 14th wasn’t just quiet; it was…

Love Against All Odds: How Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Are Prioritizing Their Relationship After a Record-Breaking and Exhausting Year DT

In the whirlwind world of global superstardom and professional athletics, few stories have captivated the public imagination quite like the…

Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Swap the Spotlight for the Shop: Inside Their Surprising New Joint Business Venture in Kansas City DT

In the world of celebrity power couples, we often expect to see them on red carpets, at high-end restaurants, or…

End of content

No more pages to load