June 1942, the Solomon Islands. Morning light slicing through scattered clouds. A Japanese Navy pilot in his Mitsubishi A6M0 rolls into a lazy turn, scanning the sky below for American fighters. His radio crackles with laughter as his wingman spots them. Six Breman F4F Wildcats climbing sluggishly through 12,000 ft, looking fat and slow.

The Zero pilot’s voice cuts through the static, dripping with contempt. Look at these American trash cans. They climb like refrigerators with wings. Watch me carve them up like training dummies. He pushes the stick forward, diving toward the wild cats, already imagining the flames.

Before we dive in, make sure you’re subscribed. Every week, we uncover the stories the world forgot. What he didn’t know was that the lead Wildcat pilot had seen him 3 minutes ago, had already briefed his flight, and was about to execute a maneuver so brutally simple that it would rewrite the Pacific Air War, not with technology, but with cold mathematics and iron discipline. The Americans weren’t flying trash cans.

They were flying the Grumman F4F for Wildcat, a tubby fighter that looked like it had been designed by a committee of pessimists. It weighed 7,952 lbs fully loaded, carried six Browning M2.50 caliber machine guns, each spitting 800 rounds per minute with 240 rounds per gun, creating a convergence zone at 250 yards where all six streams of fire met in a cone of destruction 20 ft wide.

The Radar 1830-86 Twin Wasp radial engine turned out 1,200 horsepower, pushing the Wildcat to a maximum speed of 318 mph at 19,400 ft. Service ceiling 34,900 ft. Rate of climb 1,950 ft per minute. Range with drop tank 770 mi. On paper, it was hopelessly outclassed by the Zero, which could turn tighter, climb faster, and dance circles around it.

The Zero topped out at 331 mph, climbed at 3,100 ft per minute, and could pull turns that would black out American pilots. But the Wildcat had something the Zero didn’t. 212 lb of armor plating protecting the pilot and fuel tanks. self-sealing fuel cells that could absorb bullets without exploding and a radial engine that could take 20 mm cannon hits and keep running.

It was built like a bank vault with wings. And the Americans were about to prove that survival beats elegance every single time. But first, they had to learn how to stay alive long enough to fight. In the early months of 1942, Wildcat squadrons were getting slaughtered. Pilots fresh from training. Young men with 200 flight hours in John Wayne dreams climbed into turning fights with zeros and died screaming.

The Zero could outturn anything in the sky. Try to dog fight one with suicide. VF3 flying off the carrier Lexington lost nine aircraft in 3 weeks. VF42 defending Guadal Canal from Henderson Field buried 12 pilots in 2 months. The afteraction reports read like horror stories. Engaged four zeros at 15,000 ft. Attempted scissors maneuver. Lost visual. Zero on my six.

Wingman shot down. I barely made it back. The problem wasn’t courage. It was tactics. The Navy had trained its pilots to dogfight, to turn and burn, to get into foam booth brawls at close range against zeros. That was murder. Lieutenant Commander John S. Jimmy Thatch, commanding officer of the F3, sat in a ready room aboard the Yorktown in May 1942, surrounded by exhausted pilots and empty coffee cups and said something that became doctrine.

Forget everything you learned about turning. The zero will outturn you, outclimb you, and kill you if you play his game. So don’t. We fight in pairs. We dive, we shoot, we extend. If a zero gets on your six, your wingman kills him. If a zero gets on your wingman, you kill him. We never turn. We never climb.

We dictate the terms or we die. He called it the thatch weave. And it saved hundreds of lives. The first survival legend came on June 4th, 1942 during the Battle of Midway. Lieutenant Junior Grade Scott McCuskkey flying F4F 4 number 13 off the Yorktown was on combat air patrol at 22,000 ft when 12 zeros bounced his four plane division.

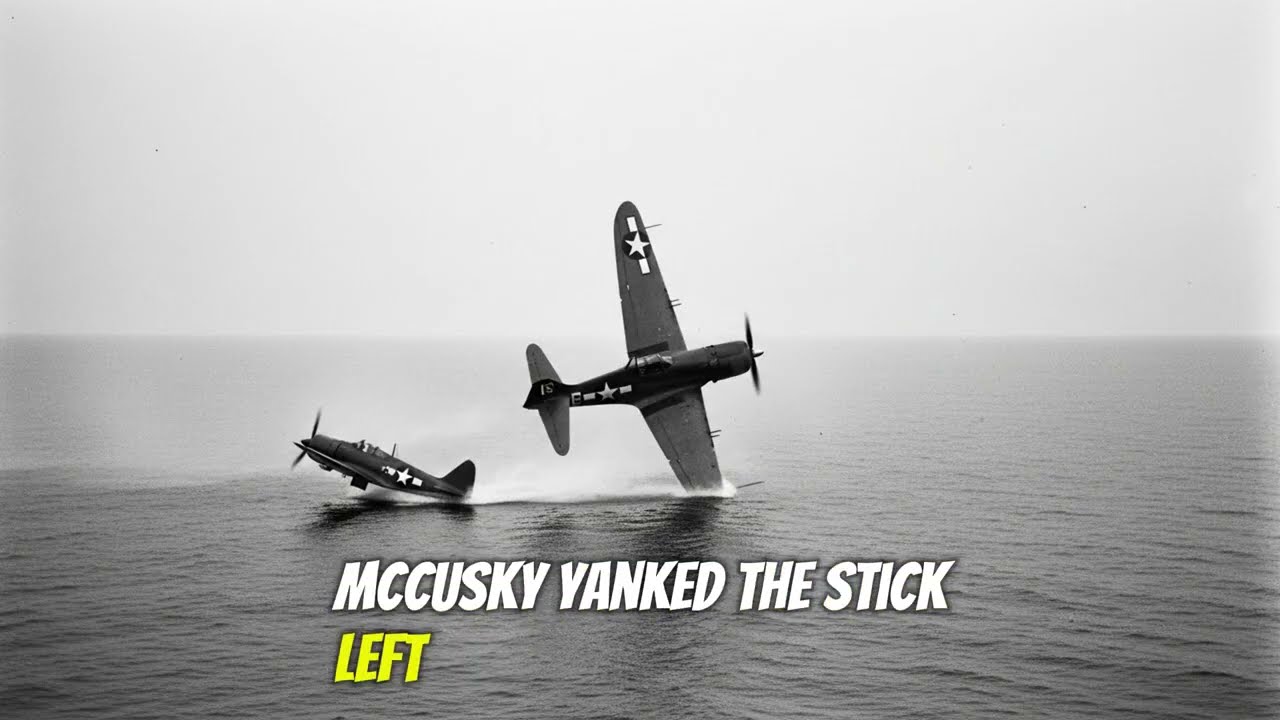

McCusky’s women died in the first pass, canopy shattered, aircraft tumbling into the sea trailing smoke. McCusky broke left hard pull for GS and felt the Wildcat shutter as the Zero’s 20 mm cannon shells stitched across his right wing. Two rounds punched through the aileron, one more through the engine cowling. The radial engine coughed, bulched black smoke, then kept running. Pistons hammering, oil pressure holding.

McCusky rolled right, dove for the deck, pushed the throttle to the firewall. The airspeed indicator climbed past 280, past 300, past 320 mph in the dive. The zero followed, closing slowly, firing in short bursts. McCusky leveled out at 500 ft above the wave tops. Saltwater spray misting his canopy. Engine screaming.

The Zero pulled up behind him. Close now, maybe 200 yd. McCusky yanked the stick left, then right, then left again. Violent jinking, skidding the Wildcat through the air like a drunk driver. The Zero pilot fired again, tracers arcing past McCusky’s canopy, close enough to see individual rounds.

Then McCusky’s wingman, Lieutenant Junior Grade William Leonard, who had circled back instead of running, came screaming down from 8,000 ft in a near vertical dive, triggered a 650s at 400 yd, and walked a convergence, zoned straight through the Zero’s engine. The Japanese fighter exploded, engine block spinning into the ocean, and Leonard pulled up in a chandel waggling his wings. McCusky’s Wildcat, trailing oil and smoke.

Limp back to the Yorktown with 47 bullet holes, a dead radio, and hydraulics so shot up he had to hand crank the landing gear down. He touched down, taxi to the side, shut down the engine, and climbed out. The plane captain, a chief petty officer from Alabama named Ray Stubs, walked around the aircraft counting holes and said, “Son, you just proved Grman builds flying tanks. Any other bird would have dropped you in the water 10 mi back.

” McCusky just nodded, lit a cigarette with shaking hands, and said, “Tell Grimman thanks.” The second vignette unfolded two months later on August 7th, 1942. During the initial landings at Guadal Canal, Marine Fighter Squadron VMF 223 flying F4F 4S from Henderson Field, a barely operational strip carved out of canny grass and mud, launched 16 aircraft to intercept a raid of 180 fighters escorting nine Mitsubishi G4M bombers.

The Wildcats climbed to 18,000 ft, positioned themselves up sun, and waited. The Japanese formation drawn toward Guadal Canal in tight V’s. Confident, almost lazy, the Wildcat leader, Captain Marian Carl, clicked his radio twice, the signal to attack, and the 16 fighters rolled in from above and behind, diving through 15,000 ft at 350 mph.

Carl picked a zero on the left flank, centered it in his gun sight, and squeezed the trigger at 300 yd. The 650s roared, a sound like tearing sheet metal amplified a thousand times. The convergence zone, six streams of armor-piercing and incendiary rounds meeting in a 20-foot cone, enveloped the Zero’s fuselof. The fighter came apart in midair, wings folding, tails shearing off.

Pilot still strapped in the cockpit as the wreckage tumbled toward the jungle below. Carl didn’t watch it fall. He was already extending, pushing his Wildcat back up to 12,000 ft, gaining altitude, setting up for another pass. The other wild cats followed doctrine. Dive, shoot, extend, climb, repeat. No turning, no chasing, just brutal, repetitive execution.

The Zeros tried to engage, pulling hard turns, climbing vertically, everything their superior maneuverability allowed. But the Wildcats refused to dance. They stayed in pairs, covering each other, diving on any zero that committed to a single target. When the fight ended, 7 minutes of screaming chaos above the jungle.

Six zeros were burning in the trees. Two more were trailing smoke toward Rabal and the bomber formation had been scattered. The MF 223 lost one wildcat. The pilot bailing out over Tagi and swimming ashore. A captured zero pilot fished out of Iron Bottom Sound 2 days later told his interrogators, “We were told the Americans couldn’t fight. We were told their pilots were cowards. Their aircraft were inferior.

That was propaganda. They fought like wolves, patient, coordinated, ruthless. They did not panic. They did not chase. They killed us methodically. And we could do nothing to stop them. But the Wildcat kept evolving. In late 1942, Grumman introduced the F4F for successor upgrade package, improved armor behind the pilot seat, an additional 40 lbs of face hardened steel plate that could stop 20 mm cannon rounds at 200 yd, and a new reflector gun sight, the MK8 Mod 4, which projected an illuminated reticle onto an angled glass plate in front of the pilot’s face, allowing for faster

target acquisition and better deflection shooting. The gun sight changed gunnery. Instead of lining up iron sights and guessing lead angles, pilots put the illuminated pipper on the target, calculated deflection instinctively, and fired. Hit probability jumped from 2% to nearly 8%.

Still not great, but in a fight where you fired, 1440 rounds per aircraft per sorty, 8% meant kills. The improved armor also changed tactics. Wildcat pilots began accepting head-on passes with zeros, something they’d never dared before. A head-on pass closed at 600 mph combined. Both pilots fired at pointlank range, and whoever flinched first died. The Zero had no armor, no protected fuel tanks.

A single 50 caliber round through the engine or cockpit was a kill. The Wildcat could absorb hits and keep coming. Pilots started calling these encounters chicken runs, and they almost always ended the same way. The Zero pulled off first, and the Wildcat pilot stitched him as he turned. The sound of the improved Wildcat became a signature.

The deeper throaty roar of the R 1830 at full throttle, combined with the staccato hammer of 650s firing in unison, echoed across Pacific ats from Guadal Canal to Terawa. Japanese troops on the ground learned to recognize it. American fighters inbound and Dove for cover. Range became the next problem to crack. The Wildcats internal fuel gave it roughly 845 miles of range, enough for defensive patrols around carriers or island bases, but not enough to escort bombers deep into enemy territory or loiter over contested zones. Grumman’s solution was the 58gal Centerline drop

tank, a streamlined external fuel cell that bolted beneath the fuselage and could be jettisoned in combat. With the drop tank range extended to 1,15 mi, giving Wildcat pilots an extra 30 minutes of combat time or the ability to strike targets 200 m farther out. The tanks became standard by early 1943, and the effect was immediate.

Suddenly, American fighters could range across the Solomons, could escort dive bombers to Rebel, could patrol shipping lanes far from friendly bases. The Japanese, already stretched thin, found themselves with no safe zones. A captured logistics document from Rabbal, dated March 1943, complained, “American fighter patrols now extend to our forward airfields.

Resupply convoys are being attacked 300 km from Guadal Canal. We cannot move reinforcements by day. Morale among flight crews is deteriorating. The drop tank, a simple aluminum cylinder holding 58 gallons of aviation gasoline, had turned the Wildcat from a defensive weapon into an offensive scalpel. The role shifted with the range.

Wildcats, originally tasked with fleet defense and combat air patrol, began flying ground attack missions, strafing Japanese airfields, supply dumps, coastal installations, anything that supported the enemy’s shrinking perimeter. The 650s loaded with a mix of ball, armor-piercing, and incendiary rounds, shredded parked aircraft, blew apart fuel trucks, and set ammunition dumps ablaze.

A typical mission log from July 1943 reads 0730 hours launched from Munda 6 F4FS dropped tanks at coast strafed Kahili airfield destroyed three zeros on ground two Mitsubishi Betty bombers one fuel Bowser light AA fire no losses returned to base 0915 hours the tempo was relentless squadrons flew three for sorties per and the cumulative damage mounted.

By mid 1943, Japanese commanders reported critical shortages of replacement aircraft, spare parts, and experienced pilots. A diary entry from a zero pilot stationed at Bugenville, dated August 1943, reads, “We have 15 aircraft, six operational, fuel for perhaps 20 sorties. The Americans fly overhead every day, sometimes twice a day. They do not engage unless we launch. They are waiting for us to exhaust ourselves.

They have already won. The respect began filtering back through prisoner interrogations and captured documents by late 1943. Japanese pilots, those few still alive with enough experience to offer informed opinions, expressed a grudging, exhausted acknowledgement of American tactics.

Lieutenant Saburro Sakai, one of Japan’s leading aces with 64 confirmed kills, was shot down over Gualokal in August 1942 and survived to write about the encounter. His post-war memoir noted, “The Wildcat was inferior to the Zero in speed, climb, and maneuverability. On paper, we should have massacred them, but the Americans refused to fight on our terms.

They used discipline, teamwork, altitude. They turned our advantages into irrelevance. A zero pilot alone against two wild cats was a dead man. Not because the Wildcat was better, but because the Americans understood something we did not. Warfare is not about individual skill. It is about system dominance. Another pilot captured after bailing out near Vela Lavella in September 1943 told his interrogators, “We called them iron birds because they would not die.

You could hit them, see the strikes, watch smoke pour from the engine, and they would keep flying, keep shooting. Our aircraft were made of aluminum and hope. Theirs were made of armor and fury. The captured technical assessments were even more revealing.

A Japanese Navy intelligence report from October 1943 recovered from rebal after its capture analyzed the F4F for in clinical detail. Enemy fighter demonstrates inferior performance characteristics but superior survivability and firepower. Armament concentration devastating at close range.

Pilot protection allows continued combat effectiveness after damage that would destroy our aircraft. Tactical employment emphasizes mutual support and energy management. Assessment, technological inferiority offset by doctrinal superiority and industrial capacity. That last phrase, industrial capacity, was the real story. The American industrial machine didn’t just produce wildcats. It vomited them into the Pacific like a conveyor belt feeding a furnace.

Roman’s Beth Page, New York facility, running two shifts 6 days a week, completed 7,885F4F Wildcats between 1940 and 1943. 7,885. Each airframe required 12,400 rivets, 3,800 ft of electrical wiring, 92 separate hydraulic fittings, and a radial engine assembled from 2,600 precision parts. The workers, riveters, electricians, machinists, many of them women pulled into the workforce by the war.

Operated with assembly line precision, a single wildcat moved through 19 stations. Fuselov assembly, wing attachment, engine installation, fuel system integration, hydraulics, electrical, armament, final inspection, test flight. Average build time, 2,800 man-h hours, down from 4,200 hours for early production models.

The Beth Page plant consumed 180 tons of aluminum per week, 12,000 gallons of hydraulic fluid per month, 1.4 million rounds of 50 caliber ammunition for test firing every completed aircraft. Right. Aeronauticals Patterson New Jersey facility churned out are 1830 twin Wasp engines 20 per day by mid 1943 each one test run for 30 hours before shipping. The logistics were staggering.

Completed Wildcats were flown from Beth Page to San Diego, loaded onto escort carriers, transported across the Pacific to forward bases, assembled by maintenance crews, fueled, armed, and flying combat sordies within 96 hours of arrival. The entire pipeline factory floor to combat mission took 23

days. 23. The Japanese, by contrast, were cannibalizing zeros for spare parts, flying aircraft with mismatched engines, rationing ammunition to 10 rounds per gun per sorty. A comparison. In July 1943 alone, Breman delivered 312 F4F for Wildcats to the Navy and Marines. Japan produced 286 A6M that month and lost 340 in combat. The mathematics were extinction.

Meanwhile, Grumman was already rolling out the Wildcat successor, but the F4F kept fighting, kept killing, kept proving that simple, rugged, wellsupported beats elegant and fragile every time. Production shifted to General Motors Eastern Aircraft Division in 1943, which built another 5,280 Wildcats designated FM1 and FM2 with improved engines, reduced weight, and better climb performance.

The FM2 powered by a 1,350 horsepower right 1820 engine could climb at 3,650 ft per minute and reach 332 mph at 28,800 ft. It wasn’t a new aircraft. It was the Wildcat refined, optimized, made even more lethal, and they kept coming month after month. An avalanche of stubby fighters pouring into the Pacific theater.

By late 1943, every escort carrier, those small, slow jeep carriers built on Merchant Hull, carried a squadron of Wildcats. Every Marine airfield from Guadal Canal to Terawa had Wildcats on strip alert. Every Navy task force had Wildcats flying combat air patrol. The Japanese couldn’t sink them faster than America could build them.

Couldn’t shoot them down faster than new pilots graduated from training. could now produce the industrial colossus, grinding them into dust. The Wildcat’s most critical test came when it faced Japan’s evolved threats. The Mitsubishi A6M50, a faster, more heavily armed variant introduced in late 1943 and the Nakajimaki 848, a new Army fighter that could match American performance in speed and firepower.

The A6M5 topped out at 351 mph, carried heavier 20 mm cannons with more ammunition, and featured improved armor protection. The Key 84 was even better. 388 mph for 20 mm cannons, self-sealing fuel tanks, and a climb rate that rivaled anything in the Pacific. On paper, the Wildcat was hopelessly outclassed again. In practice, the same tactics applied.

discipline, teamwork, energy management, and the coal calculation that two wildcats could kill any single enemy fighter regardless of performance. On November 20th, 1943, during the invasion of Terawa, Marine Fighter Squadron VMF 224 engaged a mixed formation of 12 A6M50 and six K84s trying to attack the landing fleet.

The 16 Wildcats, eight FM2s, and eight older F4F4s climbed to 20,000 ft, positioned themselves between the Japanese formation and the fleet, and waited. The enemy aircraft came in low and fast, trying to slip under the combat air patrol, and hit the transports, unloading Marines onto the bloody beaches.

The MF224’s commander, Major Robert Fraser, rolled in from above with his entire squadron, diving through the Japanese formation at 400 mph, splitting them apart. The Wildcats didn’t engage individually. They attacked in pairs, one high, one low, covering each other, refusing to turn, executing textbook thatch weaves.

Fraser personally flamed two zeros in a single pass. Dove fired, extended, climbed, dove again, fired again. His wingman, First Lieutenant Thomas Gregory, caught a key. 84 trying to climb away and stitched it from engine to tail. The Japanese fighter rolling inverted and spinning into the ocean, trailing fire. The fight lasted 9 minutes. When it ended, seven Japanese aircraft were burning in the water or scattered across Terawa’s reef.

Three more limped away trailing smoke and probably didn’t make it home. VMF 224 lost one wildcat. The pilot bailed out and was picked up by a destroyer 30 minutes later, bruised but alive. A captured Japanese pilot fished from the water near Bio Island told his marine interrogators, “Your wildat is slow.” “Your wildat is ugly, but your pilots fly like demons and there are always more wild cats. Always.

We shoot down two for more appear. We damage one, it returns the next day. You have made war into mathematics and we cannot solve the equation. The proof of inevitability came during Operation Flintlock, the invasion of the Marshall Islands in January and February 1944. 96 Wildcats spread across escort carriers Liskum Bay, Coral Sea, and Corodor flew 1,847 combat sordies in 31 days, providing combat air patrol, close air support, and anti-shipping strikes.

They shot down 63 Japanese aircraft, destroyed 127 on the ground, sank four cargo vessels, and damaged countless coastal installations. Wildcat losses 11 aircraft, seven pilots. The kill ratio, 5.7 to1 in the air, counting only aerial combat, didn’t capture the full picture. The Japanese couldn’t replace what they lost.

A radio intercept decoded by Navy intelligence on February 18th, 1944, captured a transmission from the Japanese fourth fleet headquarters to Imperial Navy Command in Tokyo. Marshall Islands lost. Air defense ineffective against sustained carrier operations. Enemy fighters maintain continuous patrols. Cannot reinforce. Cannot resupply. Request permission to evacuate remaining personnel.

The response came 12 hours later. Evacuation denied. Hold position. Reinforcements on route. The reinforcements never arrived. The Americans had already moved on to the next island, the next atal, the next step toward Japan. And the Wildcats kept flying, kept hunting, kept killing. The numbers compiled after the war told a story of systematic dominance achieved not through technological superiority, but through tactical discipline and overwhelming production.

Between 1942 and 1945, Wildcats flew approximately 96,000 combat sordies in the Pacific theater. They claimed 1,327 confirmed aerial victories, shootowns witnessed and verified against 178 aircraft lost in air combat. The kill ratio 7.46 to1. But the deeper statistics revealed the true impact. Wildcats destroyed an estimated 800 Japanese aircraft on the ground during strafing attacks, sank or damaged 127 naval vessels and merchant ships, and provided closeair support for dozens of amphibious landings from Guadal Canal to

Ewima. The average Wildcat pilot entered combat with 280 hours total flight time, 65 hours in type, and live fire gunnery training where they actually shot at tow targets over the Gulf of Mexico or Chesapeake Bay. The average Japanese pilot by mid 1943 had 150 hours total flight time, 40 hours in type, and had never fired his guns in training due to ammunition shortages.

The training differential was death. The fuel expenditure told its own story. The US Navy moved 8.6 million gallons of aviation gasoline to Pacific forward bases in January 1944 alone. The Japanese Navy had perhaps 400,000 gallons remaining across all of its Pacific holdings. 400,000 enough for maybe 2,000 sorties. The ammunition comparison was even starker.

American factories produced 1.8 8 billion rounds of 50 caliber ammunition. In 1943, Japan produced 94 million rounds of 7.7 mm and 20 mm combined. The sorty rates completed the picture. In February 1944, US Navy and Marine Wildcat squadrons flew an average of 127 sorties per squadron per week. Japanese fighter squadrons averaged 31 sorties per squadron per week and were losing aircraft faster than they could fly them.

The Wildcats ground attack missions in 1944 and 1945 accelerated Japan’s logistical collapse. Flying from escort carriers supporting the island hopping campaign. Wildcats ranged across bypassed Japanese garrisons, cutting them off from resupply, destroying coastal installations, sinking barges, and small craft trying to evacuate personnel.

A single four plane division armed with 50 caliber API and incendiary rounds could destroy a fuel dump, stray a bivwack area, and sink three barges in under 20 minutes. The cumulative effect was starvation. Japanese garrisons on truck Rabal Weiwac and dozens of smaller islands reported critical shortages of food, medicine, ammunition, everything.

A captured diary from a Japanese soldier on Mayus Island dated March 1944 read, “No ships come. The American fighters circle overhead like vultures. We try to fish at night. They found us with flares and machine gunned the boats. We are eating roots and insects.” The officers say relief is coming. No one believes them anymore.

The Wildcat pilots, many of them just 20 years old, became executioners of Japan’s outer perimeter, flying three and four sorties a day, returning with gun barrels hot enough to blister paint. Wings and fuselof stre with gunpowder residue and hydraulic fluid from targets shredded at point blank range. The acknowledgement, bitter, exhausted, complete, came through in the post-war interrogations and memoirs.

Saburo Sakai, the ace who survived the war, wrote in 1957, “The Zero was a beautiful aircraft, the finest fighter of its generation, but beauty does not win wars.” The Americans understood this. They built the Wildcat, which was ugly, slow, and tough as a battleship. They built thousands of them.

They trained their pilots to fight as teams, not individuals. They used tactics that negated our advantages and exploited our weaknesses. And they never stopped coming. That is why we lost. A Japanese Navy technical officer interviewed by American historians in 1946 admitted, “We studied captured Wildcats.

We were astonished by the simplicity of design, the heavy armor, the redundancy. Our aircraft were built for performance. Yours were built for survival. In a short war, performance wins. In a long war, survival wins. We did not understand this until it was too late. The diaries of Japanese pilots echoed the same themes.

One entry dated July 1944, found in a crash zero on Saipan, reads, “Engaged four wild cats today. They did not chase me. They did not panic. They worked together, covering each other, patient and methodical. I expended all my ammunition and hit nothing. They damaged my aircraft and I barely made it back. I do not think I will survive this war. The Americans have too many aircraft, too much fuel, too much of everything. We are fighting an avalanche with shovels.

The war in the Pacific ground toward its conclusion, and the Wildcat, gradually replaced by the faster F6F Hellcat and F4U Corsair, flew its last major combat missions in 1945 during the Philippines campaign and Okinawa. But even in the war’s final months, wildcats were flying.

From escort carriers providing anti-ubmarine patrols, from island bases running combat air patrols over bypassed garrisons, from training field stateside, where the next generation of Navy pilots learned the fundamentals of carrier aviation. On August 15th, 1945, when the war ended, 1,847 Wildcats remained in operational service across the Pacific.

The crews shut down the engines, tied down the aircraft, and walked away into the sudden, disorienting peace. A maintenance chief on the escort carrier Rudier Bay. A man named John Kowalsski from Pittsburgh ran his hand along the cowling of an FM, two that had flown 213 combat missions without an abort, and said quietly, “You weren’t the fastest.

You weren’t the prettiest, but you brought every one of my boys home. That’s all that mattered. Today, a Grumman F4F for Wildcat sits in climate controlled stillness on the floor of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, surrounded by velvet ropes and reverend crowds. The paint is faded, the tires are flat, the guns are deactivated, and the propeller is locked in place. Children press their faces close to read the placard.

Parents take photos and tour guides explain how this stubby fighter helped turn the tide in the Pacific. The aircraft is silent, static, a museum piece. But somewhere in the archives, preserved in fading ink on yellowed paper is an interrogation transcript from June 1942. A Japanese zero pilot shot down over midway and fished from the water by an American destroyer is asked what he thinks of the F4F Wildcat. His answer, translated from Japanese, reads, “We laughed at them.

We call them flying trash cans, slow and graceless. We thought the war would be easy.” The interrogator asks. And now the pilot is silent for a long moment, then says, “Now I know that Americans do not build aircraft to be beautiful. They build them to win, and they do not stop building until the war is over.

That is something we never understood.” The interrogation ends there. But the lesson echoes forward through 80 years, whispered in the wind that moves through museum halls and across forgotten air strips in the Pacific. A truth carved into history by rivets and armorplate and the courage of young men who refused to turn, refused to panic, and claimed the sky one brutal, disciplined engagement at a time.

If you love untold stories from history’s darkest hours, subscribe and join us on the next mission through

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load