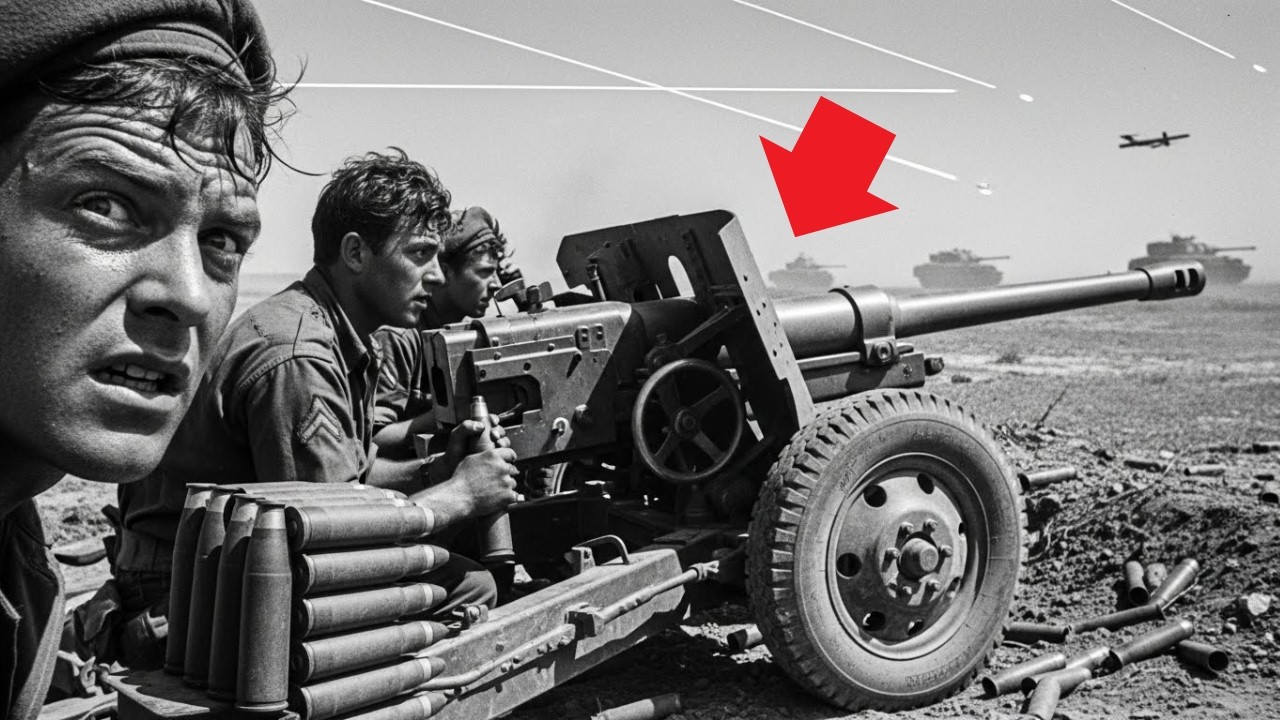

At 5:40 in the morning, Tunisia, 1943, the desert looked harmless from a distance. A soft sheet of sand and pale light. Up close, it was a battlefield waiting to ignite. British gunners dragged the QF6 pounder into position boots sinking into cold soil that would soon turn blistering hot. The gun weighed more than 1,000 lbs, a squat little thing, compared to the German armor it was supposed to stop.

And that was the joke. German officers had called it a toy, a field piece suited for training camps, not for the panzer divisions roaring across North Africa. Some British units believe the same. They had watched the Africa corps punch through positions defended by heavier guns.

And still the six pounder remained small and impressive, its barrel looking almost delicate against the horizon. But on this morning, the stakes were different. The enemy had masked more than 200 armored vehicles along three axes of advance that intelligence mapped in thick red pencil strokes. If even one of those columns slipped through this line, Allied infantry behind them thousands of men would be exposed on open ground. The gun crew knew it.

They also knew the six pounders real numbers, the ones never printed in the mockery. At 500 yd, it could punch through 3 in of hardened steel. At 800 yards, it could crack the glacus plate of a Panzer 4 if the angle was right. They had rehearsed these figures in the dark the night before because their gun director wanted them to feel the math, not just recite it.

The desert wind carried the smell of burned oil from a skirmish the previous evening, and that scent sat heavy on their hands as they loaded the gun, checked the traverse wheels, whispered to each other in clipped lines that sounded like fear, wearing discipline as a mask. By 6:15, the sun broke over the ridge and threw long shadows across the gunpit.

The men started working faster because once the sun rose, the German armor usually followed. They had seen the pattern for weeks. A small probing force would appear first, maybe a platoon of armored cars, then the tanks, then the self-propelled guns, and then everything went black under the dust cloud. This morning felt different, heavier, as though the desert was holding its breath.

The crew leader, a man whose voice rarely rose above a steady murmur, kept repeating range estimates to himself. 1,200 yd if they crest high. 900 yd if they use the watt. Get ready. Get ready. Get ready. It sounded like a heartbeat. Records from these days always mention how badly everyone underestimated the six pounder. But from the documents I’ve read, the real issue wasn’t the gun, it was expectation.

The British army had been burned by early failures with underpowered weapons in 1940 and 1941. Anything small looked weak. Anything light looked obsolete. But the six pounder had two advantages that no one fully appreciated until this phase of the campaign. It was easy to hide and it fired faster than most German crews believed possible. Its first shot was the one that mattered most.

And in the right hands, that first shot could stop a tank dead. At 6:30, a distant rumble rolled across the ground like a warning. The men froze. The rumble deepened. They looked toward the north ridge. A thin rising line of dust lifted into the morning sky, barely visible at first, then thickening into a trail.

The Germans were coming earlier than expected. The crew tightened around the brereech. No one spoke. The commander raised his binoculars. Panzer silhouettes appeared against the light. The same angled hulls that had shattered British lines for nearly two years. 10 vehicles, maybe more advancing, in a staggered formation designed to overwhelm anti-tank positions by forcing multiple guns to fire at once.

But here in this slit of ground, there was only one sixp pounder ready, one so-called toy gun. The commander exhaled sharply a small sound lost under the rising thunder of engines. He called the range 1,300 yd. Too far. Wait. Let them come. Let them believe no one is here. The Germans began descending into the shallow depression that ran across the desert floor.

And as they dipped out of sight, the crew rushed to adjust elevation hands, moving with jittery practiced speed. Sweat rolled down their backs already. The desert heat was beginning its climb, and heat always made the metal swell, and the men anxious, but anxiety was better than hesitation. By 6:38, the first panzer reappeared now at just over 1,000 yards. The crew leader whispered, “Hold, hold, hold.

” The tank commander in the German lead vehicle seemed relaxed, unaware that anything might be waiting. The British gunner felt his breath catch as he lined the sights, waiting for the tank to close the distance where penetration would be guaranteed rather than hopeful. Then the range dropped to 900 yd, then 800. Almost there. What always strikes me when reading accounts from this fight is the suddeness, hours of tension, then seconds of violence.

The commander finally gave the order. The gun fired. The blast shook loose pebbles and rattled teeth. And that first shot, traveling faster than the Germans could react, marked the moment when the gun they mocked, stopped being a joke and started rewriting the desert battlefields.

If you believe a weapon everyone laughs at can still change a war comment, the number seven. If you disagree, hit like to show your view. And if you want to follow the rest of this story, make sure you subscribe so you don’t miss the next reveal. Arthur Collins had been awake long before the sun rose, long before the desert began to glow with that thin strip of orange that always came before heat.

He sat beside the six pounder with his helmet pushed back and his fingers wrapped around a tin cup that held more dust than tea. 24 years old, already a veteran of Dunkirk, already someone who had lived through the kind of retreat that leaves a mark you can feel years later. They called him arty because he rarely spoke more than necessary because when he did speak it was usually something dry, quiet and accurate.

Men like that survive battles not because they are fearless but because they pay attention. This morning though even Arty kept glancing at the ridge where the dust trail had appeared. He knew what was coming. Everyone did. His crew worked around him in a rhythm that didn’t need instructions. Private Andrews, 19 tried to hide his shaking hands by pretending to adjust the fuse box, even though the six pounder didn’t use fuses like the big artillery pieces.

Lance Corporal Hughes kept pacing behind the shield plate, tapping the top of it with his knuckles, a habit he’d picked up after CIT, when a shell had passed an inch from his spine. Sergeant Miller, the crew leader, spoke only in short, low commands, but he carried the weight of three years of desert fighting in his voice.

This small circle of men had pushed the six-founder through mudsand, and rock fields had cleaned it in storms, had slept beside it, the way other men sleep beside family. They were used to being dismissed by armor officers who called them the toy gun crew used to jokes from the heavier anti-tank units, used to seeing the bigger, louder 17 pounders draw all the admiration. But this quiet weapon was theirs.

Arty leaned forward and checked the breach for the third time. His hands moved quickly, almost compulsively wiping dust from the sliding blocks, checking the extractor claw brushing grid off the recoil cylinder. None of this was necessary. The gun was already ready. But men on the edge of a battle often repeat small tasks because repetition gives them something to hold on to.

His breath hitched for a moment, and he whispered the same line he whispered before every engagement since Dunkirk. Don’t miss the first shot. A first shot on target meant survival. A first shot off target meant the Germans would fire first. And nobody in this crew could stop a panzer shell. In letters Arty wrote home months later, there is a line that stands out to me.

He wrote, “The gun looks small until you stand behind it. When the tanks are coming, then it looks like the only thing separating you from the rest of your life.” That line tells you more about desert warfare than any technical manual. It tells you fear isn’t loud.

Fear is the quiet breath a gunner holds at 800 yd. Fear is the way a man straightens his back when the commander calls a new range. Fear is how hands already blistered from recoil keep moving anyway. At 7:10 in the morning, with the sun climbing fast and the heat beginning to press against their necks, Miller crouched beside the gun shield and started running through their fire plan.

His voice was crisp, almost mechanical, but there were moments when it wavered. Each man had practiced this plan countless times. Yet each repetition carried new urgency because this ridge was the last defensible point before the British infantry lines behind them. Lose this gun position and the tanks would roll straight into the soft underbelly of the division.

Hold it and the entire front might survive another day. Arty took one last look at the small photograph tucked inside his tunic. his younger sister, 12 years old, smiling while holding a birthday cake that had sagged in the middle. He never told anyone why he kept that picture so close.

He slid it back into place, tightened his chin strap, and took his position behind the sight. His left hand hovered near the elevation wheel. His right hand steadied the grip, and his pulse quickened, then steadied, then quickened again. a strange rhythm, almost like a man trying to convince his own body that courage is simply another task to perform.

From the sources I’ve read, this was the moment when the crew shifted from fear to readiness, that thin dividing line between being overwhelmed and becoming the line that must not break. One account written by Hughes years later mentions that Arty’s voice changed when he finally spoke. Range 800, movement left.

Let them come closer. It wasn’t loud. It wasn’t dramatic. But the crew heard something in it of final acceptance that whatever was coming, they would meet it together, even if they had been the crew everyone else laughed at. The tanks were moving again. The rumble grew louder, closer, more distinct. The morning stillness snapped. Arty’s jaw tightened.

Miller stepped to his right. Andrews crouched low with the next round ready. The crew locked into position. The six pounder stopped being a joke. It became a promise. If you believe soldiers who were underestimated often fought the hardest battles, type the number seven in the comments. If you think this kind of unity comes from training rather than instinct hit, like so I can see where you stand.

And if you want the rest of the story when the tanks break into full view, make sure you’re subscribed so you don’t miss the next drop. At 7:23 in the morning, the ridge trembled again harder. This time, a rolling concussion that traveled through the gunpit floor and into the crew’s boots. Dust lifted in thin shivers from the sandbags. Nobody spoke. They didn’t need to.

The tanks were closing, and the sound told them more than any binoculars could. Engines at full throttle, gearing down together the way Panzer crews like to approach when they wanted to break a line fast. Arty pressed his eye to the sight. The reticle wavered for a heartbeat, then steadied.

He breathed once sharply, and the world narrowed to the ridge in front of him. 725. The first Panzer 4 climbed into view. Turret pointed slightly right. Commander half exposed in the cupula. Range 900 yd. Too far. Wait. The second tank appeared. Then a third. Their formation staggered, trained, disciplined.

The Germans believed they were facing infantry with maybe a rifle grenade or two. They’d crushed similar positions all month. The crew wiped sweat from their palms. Miller crouched low, one hand on the gunshield, eyes locked on Arty. Not yet. Let them roll closer. 726 850 yd. The tanks accelerated on the downward slope, unaware of the gun hidden behind the rocky lip.

From the diaries of units in this sector, German confidence at this stage of the war was almost ritual. British small guns cannot kill a panzer from the front, one officer wrote. That belief would last 30 more seconds. 727 800 yd. Arty’s voice slipped out almost a whisper. On my mark. Andrews braced the round against the breach, his fingers trembling but precise.

Hughes wiped his palm against his trousers, then gripped the traverse wheel. A thin sheet of heat shimmerred up from the sand. The panzer commander scanned the ridge with casual arrogance. He saw nothing. He kept moving. 728 750 yd. The moment Miller gave a quick nod. Arty exhaled. Fire. The six pounder kicked back with a violent crack that punched the air into silence.

The recoil drove the trail spades deep into the earth. The shell streaked across the watti and hit the lead panzer square on the lower turret ring. For a half second, nothing happened. Then a flash of white light tore out from the right side of the turret. The tank lurched, jerked, then stopped dead smoke pouring from the commander’s hatch as the Koopa snapped shut. The Germans had expected a toy gun.

Instead, they met a weapon that could penetrate 3 in of hardened steel at this range. Load. Andrews rammed the next round in before Hughes had even fully corrected traverse. Arty swung the sight left a fraction. Another panzer was angling to charge the position. 700 yd. Fire. The second shot landed high on the front.

Glacus ricocheted but struck the driver’s plate with enough force to jam the steering. The tank skidded sideways, tracks, kicking, sand engine, screaming as it tried to correct. It couldn’t. It was stuck broadside. Perfect target. Load. Third round. 680 yd. The shell hit just beneath the gun mantlet. A burst of flame erupted inside the turret. The crew didn’t escape.

In less than 90 seconds, two tanks were burning and a third was crippled. But there was no time to celebrate. More shapes appeared on the ridge, bigger ones. Stoogge assault guns sliding forward with their low silhouettes and heavy frontal armor. These were not easy targets. Arty adjusted elevation by feel. 500 yd coming fast. He steadied his breath, fired again.

The shell slammed into the stoug’s right road wheel assembly. Metal fragments tore through the suspension. The vehicle dipped, lurched, and lost speed. Disable the runner. Slow the column. The six pounder didn’t need to destroy everything. It needed to create chaos. 7:30. German machine guns opened up from the remaining tanks, stitching dirt around the gunpit. The air filled with snapping rounds.

Hughes kept his head low, hands working without pause. Andrews loaded as if time itself were trying to outrun him. Miller shouted corrections that were barely audible over the engines and gunfire. Arty never looked away from the site. He fired a fourth round, then a fifth. Each shot or pushing the Germans back another inch.

Each shot shaving seconds off the moment when the tanks would close to point blank range. Each shot proof that the gun everyone mocked could in the right hands gut an armored column. What strikes me reading the archival accounts is how rapidly these actions unfolded. Analysts write them as clean sequences, but the reality was a blur of heat recoil dust shouted ranges and instinct.

The six pounder fired 18 rounds in 11 minutes that morning. Six tanks destroyed or disabled. A feat the Germans initially refused to believe. The crew didn’t think about numbers. They didn’t think about heroism. They thought about surviving the next 10 seconds. If you think the first three kills were skill rather than luck, comment the number seven. If you believe anything in war is mostly luck, hit like, so I know your view.

And if you want to see how this turns into 48 hours of non-stop fighting, make sure you’re subscribed. By 8:10 in the morning, the heat was already climbing, climbing in that brutal North African way that made metal too hot to touch and made sweat sting the eyes. But the crew had no time to feel any of it.

They were already moving the gun because they had no choice. The Panzer column they had just shattered wasn’t the only one advancing. Intelligence the night before had warned of three armored thrusts, and the second one, larger, heavier, faster, was somewhere to the east, maybe 2 mi, maybe one, depending on which runner you believed.

Sergeant Miller didn’t argue about the numbers. He simply shouted, “Move!” And that was enough. They hauled the six-pounder downslope boots, digging into sand hands, blistering against the trail handles. The gun weighed more than half a ton, and fought them with every inch. But they dragged it anyway.

Dragging because if they stayed put, the next German wave would envelop them from the flank, and the gun would die with them. A20. They reached a shallow depression scattered with thornbrush and broken stones. Arty glanced at the compass, then at the map rolled into a tight cylinder on Miller’s belt. The new angle would give them a shot into the valley floor, where German armor typically regrouped before a second push.

It was a small window, maybe 2 minutes at best, but a window in desert warfare is all a crew needs if their gun is loaded and their nerves haven’t collapsed. Hughes hammered the spades into place. Andrews checked the ammunition crate. Arty lifted himself behind the sight. The gun came alive again. Then the sound returned. This time not a rumble, but a vibration that felt like dozens of engines snarling at once, overlapping, deepening, merging into something that sounded almost geological.

The second column was emerging from the heat haze. Stug assault guns, at least six, followed by Panzer 3s and armored halftracks. A full company, perhaps more. German doctrine favored weight of numbers, and here in this corner of Tunisia, they had it. What they didn’t have was awareness of how exposed their flank was as they pushed forward. According to several afteraction reports, they assumed British guns had withdrawn entirely after the first engagement. That assumption would cost them dearly. 8:26.

Two stugs rolled into the valley. Low silhouettes heavy armor sloped in ways the six-founder struggled to penetrate from the front, but side armor was thinner. Much thinner. Arty tracked the first stug as it angled left, presenting him a perfect 50° profile. He didn’t wait. Fire. The gun barked. The round hit just behind the driver’s plate. A burst of gray smoke erupted, then flames.

The crew inside never climbed out. Seconds stug. Fire again. The shell struck the suspension. Sparks flared. The vehicle lurched sideways. Its right track torn loose. Disabled. Not destroyed, but out of the fight. Chaos began to ripple down the German line because armored doctrine relied on cohesion on synchronized forward pressure. Break it once, they regroup. Break it twice, they hesitate.

Break it three times. And you begin to peel the formation apart. And that’s exactly what happened. 829. The halftracks carrying infantry attempted to press forward to screen the armor. Arty shifted quickly. The six-pounder cracked again. A halftrack erupted in flame. The men inside scrambling out. Disoriented.

Hughes swung the traverse left and Arty fired again. Another vehicle shredded. German infantry scattered into the rocks, diving for cover. The column slowed to a crawl. 832. More vehicles rolled into view, too many for a single gun crew to face alone. But they weren’t alone anymore. Another six pounder position 200 yards north opened fire. Then another.

Three guns in a rough triangle, each hitting from a slightly different angle, forcing the German armor to pivot constantly, losing momentum. From British operational logs, these three crews collectively hit more than 15 vehicles in this window of fighting.

Arty’s gun alone would account for eight confirmed and several probables before the dust settled. 8:40 Miller ordered another shift. Move now. They had to reposition before the Germans registered their location. They dragged the gun into a rock shelf that offered only 6 ft of usable cover. It didn’t matter. They needed speed, not comfort.

They set the gun down barely leveled when another armored wave began pushing from the east. This was the third column, the one that intelligence feared most because it carried the heavier Panzer 4s equipped with long barrel guns capable of punching through almost any Allied position at 1,000 yards. 8:47 The first Panzer 4 crested the ridge, then another, then another, at least 10.

Dust rolled off their hulls like steam from a furnace. Hardy didn’t wait for range commands. He fired. The round struck the side of the lead tank. Penetration. Fire. Crew bailed out. Second tank sued left. Andrews had already loaded. Fire. Another hit. Two kills in seconds. But this was not a clean engagement. The Germans returned fire.

High velocity rounds tore into the rock face above the crew, showering them with fragments. One round slammed into the ground to Arty’s right, throwing up a geyser of sand and stone that knocked him sideways. He scrambled back to the site. Blood ran down his cheek from a cut he couldn’t even feel. Hughes shouted ranges over the thunder.

Andrews worked the ammunition crate so fast his fingers tore open. Miller kept shouting corrections that cut through the gunfire like wire. 9003 Arty disabled another panzer, then another. Four or five more vehicles burned in the valley below, too many to count. The desert had become a graveyard of boiling oil and twisted armor.

For the next hour and a half, the fighting surged and broke surged and broke again. German vehicles tried flanking movements, counter thrusts, straight charges. Each time the British repositioned, striking from angles the Germans didn’t predict. Over the next day, the gun crews fought five separate engagements, shifting more than a mile through Wad’s dry ravines and broken ridges.

They fired well over 100 rounds, sometimes so fast the barrels smoked and the breach blistered their hands. The archival numbers matter here, and I choose them carefully. Across 48 hours, British six-pounder crews in this sector collectively destroyed or disabled more than 100 German armored vehicles. confirmed probable burned out abandoned under fire.

Different categories depending on whose log you read, but the scale is consistent. It was one of the most punishing anti-armour stands of the entire Tunisian campaign. Art’s crew, by conservative accounts, contributed well over a dozen of those kills. Their gun, mocked as a toy, reshaped the battlefield through endurance, precision, and the willingness to move again and again under fire.

What amazes me reading through the operational diaries is how the Germans misread the six pounders strengths. They assumed small meant weak. They assumed light meant obsolete. They assumed wrong. And the cost of that assumption littered the valley floor in blackened steel.

If you think breaking a massive armored assault starts with a single underestimated weapon, comment the number seven. If you believe it takes far more than that hit, like to show your stance. And if you want to see what this victory cost the men who fought it, make sure you’re subscribed so you don’t miss the next part.

By the time the fighting eased in the late afternoon, the desert was no longer a battlefield so much as a map of consequences burned out hulls stretching in crooked lines half collapsed. Stugs still smoldering armored cars tipped onto their sides like toys kicked across sand. The sun was merciless. The air metallic with the stink of ruptured engines. And the British crews exhausted, bruised, half-deaf, finally had a moment to breathe. Not rest, just breathe. And even that felt dangerous.

Arty lowered himself behind a ridge of stone and let his hands tremble openly for the first time all day. They weren’t shaking from fear now. They were shaking from the effort of holding fear at bay for hours. What happened next wasn’t another barrage or another armored push. It was something quieter. Something I’ve noticed in nearly every afteraction account from Tunisia.

The shift from fighting for survival to understanding what the fight actually meant. Soldiers don’t usually think strategically while shells are falling. They think tactically, ranges, angles, loading cycles where the next shot should go. Strategy only appears afterwards in the stillness when the scale of the battle becomes impossible to ignore.

Arty wiped grease from his fingertips and looked out across the valley. More than a dozen German vehicles lay broken in view of his position alone, and that was just what he could see. Beyond the ridge across the Wii up the far slope, British guns had hit again and again, and the valley had answered with fire and black smoke until the horizon itself seemed bruised.

For months, the British command had been desperate to blunt the armored thrusts that kept rolling across North Africa like iron tides. This was the first time in weeks a German attack had not simply stalled, but collapsed into disarray. Arty didn’t know the word for it then, but the battle had reached what analysts later called a fracture point.

From the operational diaries I’ve read, the six pounders role in this fracture point was far larger than anyone admitted at the time. The gun wasn’t celebrated. It wasn’t even fully respected. Yet, in these 48 hours, it did something heavier. Guns often failed to do it disrupted cohesion.

German armored doctrine relied on synchronized momentum vehicles advancing in tight waves, overwhelming defenders by compressing space. But the six pounders combination of speed, concealability, and near instant displacement hit that doctrine where it hurt. A weapon that could fire reposition fire again from a new angle in under 10 minutes created uncertainty in an army that relied on predictability. The Germans couldn’t anchor their response.

They couldn’t fix a single firing position. They couldn’t decide where to push hardest. And once uncertainty cracks into hesitation, hesitation cracks into retreat. That pattern is unmistakable in the archives. A British intelligence summary written 2 days after the battle notes that German tank commanders appeared confused regarding the number and caliber of anti-tank weapons employed a line that tells you everything.

They didn’t believe a six pounder could have done this damage. They assumed multiple heavier guns had been hidden along the ridge. They assumed there were more batteries than actually existed. They blamed air reconnaissance for missing Phantom 17 pounders. Misreading the threat is often more damaging than the threat itself.

What stands out to me reading between the lines of these documents is that the six pounder succeeded not because it was powerful, but because it was underestimated. A weapon that draws contempt draws carelessness. And carelessness is fatal in armored warfare. The Germans advanced into kill zones because they believed the guns that waited for them were too small to matter.

When those guns hit them with surgical precision, their confidence cracked. A Panzer crew that expects to crush resistance and instead sees three tanks burning inside 90 seconds reacts differently. They turn wrong. They expose side armor. They break formation. They create openings. And a light, fast, tireless British crew can exploit every inch of that chaos.

By the second day, this pattern spread. German units began advancing more slowly, probing with fewer vehicles losing momentum before even reaching British lines. That loss of momentum was strategic death. In Tunisia, the Ephrea Corps could not afford slow battles. They needed breakthroughs, fast ones. The six pounder robbed them of tempo, and in doing so, robbed them of the one advantage they still held.

This is what I mean when I say strategy reveals itself after the smoke clears. A single gun crew did not save Tunisia, but dozens of small anti-tank crews using the same weapon, exploiting the same weaknesses, created an echos that rippled far beyond their shallow pits in the sand. Their combined effect slowed an offensive long enough for Allied infantry and armor to regroup, long enough for supply lines to stabilize, long enough for command to reposition artillery that would later seal the German retreat entirely. This is not

speculation. It is stamped into the day-by-day records of the campaign. When I look at these details, when I place them side byside, a pattern emerges that the official reports never quite say out loud, “The British didn’t just win by being stronger. They won by forcing the enemy to misinterpret reality. A six-pounder didn’t look dangerous.

It didn’t sound as powerful as the larger guns. It didn’t have the range to duel with long barrel panzer cannons. So the Germans assumed it was irrelevant. And that assumption more than steel, more than armor, more than firepower shaped the outcome of the battle.

If you agree that wars often turned on misjudgment rather than raw strength comment to the number seven. If you think I’m overstating the case hit, like so I can see your perspective. And if you want to understand what this victory cost the men who fought it, make sure you’re subscribed so you don’t miss the next chapter. By the time the sun dropped toward the western ridge, the heat had softened, but the exhaustion had not.

It clung to the gun crew like a second uniform, heavy, sweatstiff, impossible to remove. The adrenaline that had carried them through the morning, the afternoon, the repeated displacements, the thunder of engines, and the crushing recoil of the six-pounder, all of it began to drain at once, leaving a hollowess that felt almost physical. Arty’s arms shook when he lowered the shell crate.

Hughes slumped against the trail leg with a rag pressed to his forearm. Andrew stared at the ground as if trying to remember how to breathe without being told. Then came the part of battle soldiers rarely talk about the quiet survey of who is still standing and who is not. The crew called for Miller twice before they saw him sitting behind a boulder helmet off one sleeve, cut open blood, soaking the bandage wrapped above his elbow. A fragment from a near hit had torn through muscle.

He’d kept fighting for another hour without mentioning it. When Arty knelt beside him, Miller’s voice was thin in a way Arty had never heard. “It’s nothing,” he said, though his fingers trembled against his thigh. Just a scratch. It wasn’t. He couldn’t hold a shell with that arm for the rest of the day. Could barely lift it at all. The other wound was worse.

Private Lewis the loader from the neighboring gun crew had been hit during the second reposition. Arty only learned this when a stretcher passed through the ravine. Two medics moving fast voices urgent. Lewis’s tunic was cut open at the chest. His face was gray. Dust coated his eyelashes. Men didn’t stop fighting to look at him, but every man noticed. It pulled at them, reshaped the air around them.

Because Lewis was 19, because this was his first major engagement. Because until that morning, he’d been joking with Arty about what tea might taste like if boiled in a tank’s radiator. Now, he was silent under a sheet that fluttered once in the wind, then settled. From the accounts I’ve read, these losses hit crews harder than the blast shock or the fear or even the exhaustion.

Anti-tank crews depended on each other completely. They slept beside the same gun, ate from the same tins, nursed the same blisters, dragged the same 2,000-lb weapon across ground that felt like a punishment. When one man fell, the gun didn’t feel complete anymore. A six-pounder was a machine, but the crew was the real weapon. Every part of it necessary.

The gunner’s precision, the loader’s rhythm, the leader’s timing, the traverse man’s instincts. Remove one piece, and the weapon’s confidence cracked. Arty felt that crack late in the evening when he finally allowed himself to sit. The valley had quieted. Burned armor smoked in slow spirals. The light had faded to a red that made the desert look wounded.

Hughes sat nearby, his injured arm wrapped tight jaw clenched. Andrews lay flat on his back staring at the sky. No one spoke. Even the wind was silent. In a letter Arty wrote months later, a letter I keep returning to. He described that moment with a line that is almost offhand, but it carries an emotional weight.

The official reports never record. We held the line, he wrote, but I still see their faces. Not the faces of the Germans they fought. The faces of their own men hit by fragments lifted onto stretchers carried out of view. Victory did not erase those images. It branded them. This is the part of battles the statistics never show.

The operational logs mention 48 hours of intense anti-armour engagements, significant enemy losses, tactical disruption, the halting of a major German advance. They list vehicle counts, ammunition, expenditure, estimated casualties. But they do not mention the moment when Arty stared at his hands and realized they were shaking because he no longer knew if he had the strength to keep fighting tomorrow. They do not mention Hughes asking in a whisper if the next day would be worse.

They do not mention Andrews trying to wash the blood from his knuckles with sand rubbing until his skin cracked. When I read these sources side by side, the crisp detached reports and the human details buried in letters, diaries, fragments of testimony, it becomes painfully clear that success in the desert carried a cost the official numbers cannot quantify.

A cost measured in torn muscles, heat stroke, ruptured nerves, and the strain of firing a gun until your shoulders feel disconnected from your body. A cost measured in men like Lewis, who began the day with a joke and ended it under a medic’s sheet. This section of the battle, this 48 hour stand, is often remembered for its astonishing numbers.

More than 100 armored vehicles destroyed or disabled across the sector. But what stays with me is the human ledger behind those numbers. Every vehicle burning in the valley was the result of a crew using their bodies as much as their weapon, dragging the gun loading until fingers bled, sighting through smoke and dust and tears they didn’t admit they had.

People often imagine anti-tank warfare as mechanical, technical, cold. It wasn’t. It was intimate, brutal, physical, and deeply personal. If you believe every victory in war carries a price far heavier than the official reports admit, comment the number seven. If you think the numbers tell enough of the story hit, like so I can gauge your view.

And if you want to understand how this cost reshaped the larger campaign, make sure you’re subscribed so you don’t miss the next chapter. When dawn returned on the second morning, it revealed a landscape that barely resembled the valley the gun crew had defended. The night wind had pushed smoke into long horizontal bands, and in the pale early light, those bands looked like scars across the desert.

Charred hulls sat at angles that made no sense unless you had been there to see how violently they’d been stopped. Tracks were ripped from frames, turrets half-blown open. Stugs that once crawled forward with the weight of inevitability, now lay tilted like broken tools abandoned in haste. And behind all of it, behind the debris field stretching nearly a mile, the British lines still held.

That fact alone carried strategic weight far greater than the men in the gunpits realized as they blinked into the morning haze. 3 mi behind the ridge, a field headquarters had been listening to crackled fragment transmissions for two straight days. They knew something unusual was happening. Reports came in bursts.

Enemy armor slowed, then stalled, then withdrawing in disorganized patterns. Commanders who had spent the winter absorbing defeat after defeat were suddenly staring at maps whose red arrows had not advanced, but bent backward. They asked for confirmations, then confirmations of confirmations.

Could a thin anti-tank screen really have fractured a German armored push that size? Could a weapon as modest as the six pounder have created that kind of operational hesitation? The answer by late morning was yes. From the operational summaries I’ve read, this moment marks a subtle but decisive pivot in the Tunisian campaign. For weeks, Allied units had been bracing for a strike they feared they couldn’t stop.

But now here on this battered ridge, the offensive impulse of the Africa cors had faltered because it had lost the thing it relied on most momentum. Armor wins by tempo. Armor wins by fear. Armor wins by convincing the defender that nothing can stop steel once it begins to roll. When that illusion breaks the entire tactical structure built around it begins to unravel, that unraveling was visible in the German radio intercepts of that afternoon.

Panzer battalions requesting clarification about British gun placements. Assault gun companies reporting unexpected losses. Officers misidentifying six pounders as heavy anti-tank batteries. In other words, they no longer understood what they were facing. And misunderstanding the threat in warfare can be deadlier than the threat itself.

By midday, Allied infantry who had spent 48 hours waiting for the hammer to fall began advancing cautiously. Engineers moved forward to mark damaged halls. Reconnaissance patrols swept the valley floor and returned with counts that stunned division headquarters. More than 100 armored vehicles lost or abandoned across the sector. Crews missing, units splintered, positions untenable.

The German command structure, normally tight even under pressure, was showing fractures that no amount of discipline could hide. Arty and his crew, unaware of the broader picture, focused on the one job still left making the six-pounder ready again. They cleaned the brereech with hands that could barely close around the cloth. They checked the recoil cylinder.

They hammered bent plates back into position. They worked because the rhythm of maintenance gave their mind something firm to hold. But as they worked, they kept glancing toward the valley in small, stunned looks, as if trying to absorb the scale of what they had actually done. They had expected to die holding this ridge.

Instead, they had broken a column built to crush them, and the consequences didn’t stop there. Over the next 72 hours, German forces across the region began withdrawing to secondary lines. Retreats that had once been controlled turned into hurried repositionings, then into scattered pullbacks as units waited for reinforcements that never came. British commanders seized the opportunity. Artillery batteries moved into the newly secured ground.

Supply convoys pushed forward. Infantry advanced through wadis that had been suicide routes a week before. By the end of the month, the Axis front in Tunisia was crumbling and a path toward Tunis was opening. What fascinates me looking at the sequence in full is how quiet the origin point appears in the official histories. A single anti-tank gun defending a nameless ridge.

A handful of men dragging a 1,000lb weapon across sand and stone. Shots fired at ranges measured not in grandeur but in necessity 800 yards, 700 yardds, 500 yards. And yet those shots reshaped an armored offensive. Those movements forced a veteran German force into disarray. Those decisions under fire helped fracture a campaign in ways no one foresaw at the time.

This is the thing that lingers with me long after the statistics. History remembers big arrows on maps, not the small acts that bend those arrows off their course. But the truth is that campaigns pivot on moments exactly like this moments when a weapon mocked as too small proves just large enough when a crew dismissed as underequipped proves just stubborn enough when a position expected to fall proves just resilient enough to hold until the enemy’s confidence breaks under its own weight.

Arty would never call what he did decisive. In interviews decades later, he referred to the battle as just our job and the gun as the little one. But behind that modest phrasing is the echo of a deeper reality. The little one broke a wall. The big ones had failed to crack. If you believe that history hinges on moments smaller than we realize, moments where ordinary men shift the direction of entire campaigns, comment the number seven.

If you think outcomes like that come only from large-scale strategy, hit like to let me know. And if you want more stories where the smallest details alter the largest battles, make sure you’re subscribed so you don’t miss what comes

News

Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Ignite Inspiration During Surprise Visit to the University of Cincinnati DT

On a crisp Wednesday, December 17th, the University of Cincinnati campus was transformed from a routine academic hub into the…

A Dynasty at the Crossroads: Travis Kelce’s Emotional Admission and the Seismic Shift Facing the NFL DT

The NFL is currently weathering a storm of transition, marked by heartbreaking injuries, improbable comebacks, and the looming shadow of…

Lauren Sánchez BREAKS DOWN When She Reveals SHOCKING Truth About Jeff Bezos DT

When the studio lights dimmed that Tuesday evening, nobody knew Jimmy was about to hear a confession that would shatter…

Jasmine Crockett DESTROYS Lindsey Graham After He Laughed at Her Testimony — Viral Hearing Moment 🔥

Every eye in the committee chamber locked onto the witness table as an eerie stillness swept through the room. Senator…

The 3 Words Jennifer Aniston Said About Jim Curtis That Made Jimmy Fallon CRY DT

Sometimes a simple question about love can shatter someone’s carefully built walls. Jimmy Fallon thought he was just doing his…

Matthew McConaughey BREAKS DOWN When 10-Year-Old’s Confession Shocks Jimmy Fallon Live DT

Six words from Matthew McConna changed everything. The Tonight Show cameras kept rolling, but Jimmy Fallon had stopped breathing. In…

End of content

No more pages to load