Congresswoman Jasmine Crockett stood beneath the bright CNN studio lights, her maroon suit reflecting quiet confidence as she prepared to face one of America’s most formidable legal minds. Moments earlier, Alan Dersowitz, the 85-year-old Harvard law professor emeritus and renowned attorney, had stepped out from backstage clutching a stack of papers, his expression firm with intent.

I’ve got the evidence that will expose the congresswoman’s lack of legal understanding, Durowitz declared to the moderator, his voice steady with the authority of a man who had argued before the Supreme Court countless times. “She might be a rising star in her party. But tonight, viewers will see she’s far out of her depth.

” The audience stirred, phones raised to record what was sure to be a heated debate. With his decades of experience, Harvard pedigree, and high-profile clientele, Durowitz appeared confident that this would be an easy win over the relatively new congresswoman who had served in Congress for only 2 years.

But Crockett didn’t flinch. The former public defender and civil rights attorney stood poised, a faint, knowing smile on her face as her eyes met his. She had prepared for this confrontation in detail, and those who knew her recognized the look. This wasn’t going to be an ordinary debate. It was about to become one of the most challenging moments in Dersuit’s long career.

As CNN’s cameras began rolling, the host introduced the segment on voting rights legislation. Neither Crockett nor Durowitz looked away during their intense staredown. The veteran legal scholar was about to learn that underestimating Jasmine Crockett would prove to be his biggest mistake on national television.

Before diving into this remarkable exchange, make sure to like this video and subscribe to our channel for more insightful political debates and analysis. You’ll want to see every second of how Congresswoman Crockett turned the tables on one of America’s most celebrated attorneys. The CNN studio buzzed with anticipation as host Rebecca Mitchell opened the discussion.

Tonight, we’re joined by two legal experts to debate the Voting Rights Protection Act currently before Congress. Harvard law professor emeritus Alan Dersowitz, who has argued before the Supreme Court and represented several high-profile clients, and Texas Congresswoman Jasmine Crockett, a former public defender and civil rights lawyer now serving her first term in the US House.

Dersowit sat upright, his silver hair neatly combed, dressed in a crisp navy suit that exuded establishment prestige. At 85, he carried the weight of decades in academia, having influenced generations of lawyers and defended clients from OJ Simpson to Jeffrey Epstein. His expression was firm.

He had not come to discuss, but to dominate. “Thank you for having me, Rebecca,” he began, his Boston accent still noticeable. “I’ve been teaching constitutional law since before the congresswoman was born. I think the public deserves to hear from someone who actually understands the legal complexities involved.

The condescension in his tone was unmistakable. He shuffled his papers, highlighting sections of the bill and previous court rulings, props meant to underline his authority. Across the table, Crockett sat composed in her maroon suit, a gold necklace catching the studio light. At 43, the Yale educated attorney had built her reputation differently, not through elite circles, but by defending everyday Americans before entering politics and later winning her congressional seat.

Her calm expression concealed the sharp legal mind that had won her numerous courtroom battles against opponents who underestimated her. “Good evening,” Crockett said evenly, her voice carrying a trace of her Texas roots. “Unlike some, I’m not here to lecture Americans from an ivory tower. I’m here to talk about legislation that impacts real voters, people I’ve represented both in court and now in Congress.

” Rebecca Mitchell nodded, sensing the growing tension. “Let’s begin with the basics.” Professor Durowitz, you’ve called this bill an unconstitutional overreach. Congresswoman Crockett, you’re one of its co-sponsors. What’s at stake here? Before Crockett could respond, Dersuitz leaned forward. What’s at stake is nothing less than the constitutional balance of power, he asserted.

The congresswoman and her colleagues want federal control over what the Constitution clearly reserves for the states. This isn’t just poor policy. It’s unconstitutional. I’m surprised anyone with a law degree would support it. The camera caught Crockett’s faint smile, not amusement, but recognition.

She had faced countless prosecutors and opposing council who used similar tactics, dismissive, condescending, and eager to undermine her expertise. Behind the scenes, her team had prepared thoroughly for this very approach, analyzing Durowitz’s debate style, his tendency to interrupt, assert intellectual superiority, and sidestep opposing arguments instead of engaging directly.

What Durowitz didn’t realize was that Crockett had spent her weekend reviewing his past writings, not just recent comments on voting rights, but also essays from the 1970s and 1980s that directly contradicted his current position. She had even spoken to three of his former Harvard students who offered valuable insights into his argumentative habits and weaknesses.

Meanwhile, in the control room, CNN producers watched closely. The segment had been framed as a substantive policy discussion, but the personal tension between the two lawyers was creating far more compelling television. The network’s social media team began uploading clips of Dersawitz’s opening remarks, anticipating that the exchange was about to go viral.

The stakes extended beyond the Voting Rights Protection Act. For Dersawitz, it was about preserving his legacy as one of America’s most prominent legal minds in his later years. For Crockett, it was about proving that a new generation of lawyers, diverse, grounded in community experience, and fearless in the face of establishment power, deserve to be heard as equals in shaping the nation’s legal future. Rebecca turned to Crockett.

Congresswoman, your response to the professor’s constitutional concerns. Crockett straightened her papers, her expression shifting from polite to focused. I’d be glad to address those constitutional points, Rebecca. But first, viewers should understand something essential about this discussion.

What people need to realize, Crockett continued, her voice firm and clear, is that interpreting the Constitution isn’t reserved for Ivy League professors. It belongs to every American, especially those most affected by its interpretation. Durowitz raised an eyebrow, opening his mouth to interrupt, but Crockett kept going.

The professor implies I misunderstand constitutional law. Let’s address that. Article 1, section 4 clearly grants Congress authority over federal elections. The 14th and 15th Amendments further empower Congress to safeguard voting rights. This isn’t advanced theory. It’s written law. Durowitz shook his head, visibly irritated.

Congresswoman, I’m fully aware of those provisions, but the Supreme Court has repeatedly affirmed state authority in election administration, notably in Shelby County v. Holder. I’m familiar with Shelby County, Crockett replied, having litigated voting rights cases directly impacted by it. The question isn’t whether states have authority, it’s whether that authority can be used to silence voters.

The professor’s face tightened. That’s precisely the kind of emotional argument that clouds this debate. The Constitution guarantees equal protection, not voting convenience. When voting restrictions disproportionately affect certain communities, Crockett countered, “That’s not about convenience.

It’s about constitutionality.” Rebecca interjected. Let’s focus on specific sections of the bill. Professor, you’ve criticized the requirement for minimum early voting days. Why? Durowitz leaned forward. This is where Congress oversteps. States differ in population and resources. A uniform federal rule ignores these realities and violates federalism.

I have statements from election officials in 17 states warning these mandates would cause logistical chaos. The congresswoman is pushing ideology over practicality. Crockett waited patiently, then responded. Interesting you mention election administrators. I have statements from 23 states, including Republicans, supporting these standards as both achievable and essential.

She turned directly to Durowitz. Let’s talk consistency. Professor, in your 1982 book, Rights of the People, you wrote that federal voting standards may be necessary when states show ongoing discrimination or failure. You specifically endorsed national early voting standards. Has the Constitution changed or just your stance? The camera caught Duroitz’s brief surprise.

He hadn’t expected her to quote his past work. Shuffling papers, he replied. Academic thought evolves with evidence. The voting landscape has changed since the 1980s. My earlier position reflected concerns about specific states at that time. So, constitutional principles shift with political climates. Crockett asked.

Interesting for someone claiming to be an originalist. The tension rose as Rebecca pivoted. “Let’s discuss voter ID laws.” “Critics say your bill weakens election integrity.” “Those critics ignore evidence,” Crockett replied. “Multiple studies, including from the Brennan Center, show voter impersonation fraud is nearly non-existent.

What’s real is that about 25 million Americans lack the required IDs,” Dersuit scoffed. The Brennan Center isn’t impartial, and suggesting millions can’t get IDs insults voters intelligence. Crockett’s tone hardened slightly. Professor, have you represented anyone who lost their vote because they couldn’t afford ID documents? I have met elderly citizens without birth certificates.

I have spoken to low-wage workers unable to visit ID offices open only during work hours. I have calling these real barriers insults shows exactly the ivory tower problem I mentioned earlier. Sensing he was losing ground, Durowitz shifted tactics. Your anecdotes don’t override state authority to protect election integrity.

The Supreme Court has upheld reasonable ID laws. Then let’s talk about that. Crockett countered in Crawford v. Marian County which upheld Indiana’s voter ID law. The court noted that evidence of actual voter burden was limited. When strong evidence shows disenfranchisement, the constitutional test changes.

She lifted another document. And in your 2005 Harvard Law Review article, you criticized judges who hide policy motives behind selective constitutional readings. You cited voter ID laws as examples of states using fraud claims for partisan gain. You’re taking that out of context, he replied. Am I? Crockett raised an eyebrow.

Would you like me to read the full paragraph? Rebecca quickly intervened. We need to take a short break. When we return, we’ll continue our discussion on voting rights and hear from viewers. As cameras paused, Dersowitz leaned toward his aid, whispering urgently and pointing at his notes. Something had clearly gone wrong.

His aid frantically searched through papers. Across the table, Crockett calmly sipped her water. A producer approached and asked if she needed anything. “I’m fine,” she said evenly, “but you might want to check on the professor. We haven’t even reached the real contradictions yet.” When the broadcast resumed, the energy had shifted.

Durowitz looked composed, but firm. During the break, I reviewed my own writings, not the congresswoman’s selective quotes. My position has always been that election laws must balance access and integrity. That’s all states are trying to do. He faced Crockett directly. But since we’re discussing credentials, let’s be clear.

I’ve argued over 50 Supreme Court cases. I’ve taught constitutional law to thousands of the nation’s top attorneys. With all due respect, your brief tenure as a state legislator and first term congresswoman hardly qualifies you to lecture me on constitutional interpretation. The condescension in his tone was unmistakable and exactly what viewers noticed.

Crockett had been waiting for this moment. “Professor,” she began, her tone calm but precise, the same one she used in court when an opposing lawyer made a critical mistake. “I think it’s time we address the elephant in the room.” “The issue,” Crockett continued, “Voice steady as steel, is that you’re relying on your credentials instead of engaging with the core of my argument.

That might work in a classroom where students worry about grades, but this isn’t Harvard law, and I’m not your student. Durowitz’s expression tightened. I’m addressing substance, he replied. You’re the one bringing up old quotes. I’m pointing out how your views have shifted over time, Crockett countered.

Let’s focus on today’s discussion. You claimed states should have brought authority over election procedures. Yet in December 2020, you argued that legislators weren’t even bound by their own constitutions when appointing presidential electors. That stance would have canceled millions of votes. She held up another paper.

You wrote, and I quote, “The Constitution gives this power to state legislators, not to states generally. How do you reconcile that with your current concern for federalism?” Durowitz shifted uneasily. That was a narrow legal argument about the electors clause, not general election regulation. Is it? Crockett interjected.

Because both deal with the same constitutional principle, balancing federalism with protecting the right to vote. Yet your interpretation seemed to change depending on which political side benefits. The audience murmured as Dersuits flushed. That’s absurd. My positions are based on constitutional analysis, not politics.

Crockett nodded slightly. Then let’s review that analysis. You often cite Shelby County v. Holder to argue against federal oversight of state voting laws, but in that very ruling, Chief Justice Roberts reaffirmed Congress’s authority to address voting discrimination authority this bill uses. She leaned forward.

The difference, professor, is that I’ve represented real voters impacted by Shelby County. I’ve seen polling places shut down in minority areas, voter role purges that disproportionately target eligible minority voters, and ID laws crafted with precision to exclude certain communities. Durowitz tried to interrupt, but Crockett raised a hand.

Please, I listened respectfully to you. He went silent, realizing the shift in tone. You mentioned your Supreme Court experience, she continued. I respect that. But I’ve worked in state courts where voting rights directly affect people’s lives. I’ve helped seniors reclaim their right to vote after bureaucratic hurdles.

Constitutional theory meets real life in those cases, not academic debate. Lifting the bill text, she added, “This legislation doesn’t federalize all elections as you claim. It simply sets minimum standards to prevent the worst forms of voter suppression. States still retain broad flexibility in how they apply it.

Mitchell sensed the turning point and turned to Duruititz. Professor, your response. Durowitz composed himself. The congresswoman’s experiences are valid, but they don’t override the Constitution. It gives states, not Congress, primary authority over elections. This bill exceeds that by micromanaging procedures.

Section 306 alone includes 42 detailed mandates on early voting hours and locations. That’s not a standard, it’s a takeover. Crockett smiled slightly. I’m glad you brought up section 306, professor. It’s modeled on a proposal you supported in congressional testimony back in 1991. You described similar measures as appropriately tailored federal actions that respect state authority while ensuring access to the ballot.

The room went silent as Crockett displayed the transcript. This is from your House Judiciary Committee testimony, March 14th 1991. Would you like me to read it?” Dersowitz blinked rapidly, caught off guard. “I’d need to see the full context.” “Of course,” Crockett replied, sliding the document toward him. “Take your time.

” As he read, the camera captured his expression shifting from confidence to confusion to quiet dismay. The text confirmed exactly what she’d said. Crockett turned toward the camera. This highlights my main concern. Too often, voting rights are discussed as legal theories instead of real protections that affect real people.

The same experts who once supported federal voting safeguards now oppose them, not because the Constitution changed, but because political interests did. Durowitz trying to recover said, “Even if I once supported similar provisions, and I’d need to confirm that the constitutional framework has evolved through later Supreme Court rulings.

” “Which one specifically?” Crockett asked evenly. “Because Shelby County still upheld Congress’s power to address voting discrimination, requiring only updated criteria for oversight. That’s precisely what this bill does based on current evidence.” She turned back to Mitchell. Rebecca, the real question isn’t abstract constitutionality.

It’s whether every American deserves equal access to the ballot, regardless of zip code, schedule, or ability. The Constitution’s history and text clearly give Congress the duty to act when that access is under threat. Durowitz, now visibly unsettled, shuffled his papers as the audience waited in silence. Crockett was accused of appealing to emotion rather than relying on constitutional logic.

She raised an eyebrow. Am I? Then let’s get specific about the legal reasoning. Article 1, section 4 clearly states that the times, places, and manner of holding elections for senators and representatives shall be determined by each state’s legislature, but that Congress may at any time make or alter such regulations.

The text directly grants Congress ultimate authority. Furthermore, she explained, “The 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause and the 15th Amendment’s ban on racial discrimination in voting both contain enforcement clauses, giving Congress explicit power to enact appropriate legislation. The Supreme Court has consistently upheld this authority, most recently in Bernovich v.

DNC, which while upholding Arizona’s election rules, reaffirmed Congress’s power to set voting rights standards.” The studio fell silent as Crockett methodically dismantled Dersawitz’s constitutional objections, citing case law, historical precedent, and exact provisions of the bill with striking precision.

It was a lesson in constitutional reasoning delivered not from theory, but from lived experience. Durowitz attempted several interruptions, yet each time Crockett countered smoothly, demonstrating superior command of both the law and the bill’s details. His growing frustration was evident.

Finally, in a last effort, he tried what he believed was his strongest point. Congresswoman, with all due respect, I don’t think you understand the unintended consequences of this legislation. Section 502 could actually weaken minority voting power in certain local elections. Crockett’s smile widened slightly.

Professor, I’m afraid that’s incorrect. There is no section 502 in this bill. It contains only 428 sections. The room went completely still. Durowitz hurriedly shuffled through his papers, realizing too late he had confused this bill with another. A serious mistake for someone claiming expert knowledge. I apologize, he said, voice quieter now.

I meant section 402. Crockett responded evenly. Section 402 deals with ballot dropbox. Professor, it has nothing to do with minority vote dilution. Perhaps you’re thinking of HR2722 from the last Congress. That was a separate bill entirely. The moment captured what had been unfolding all along.

Despite his credentials, Dersowitz had entered the debate without fully reading the legislation, relying instead on talking points. Crockett, who had helped draft portions of the bill, displayed deep understanding and accuracy in every response. Sensing the significance of the exchange, moderator Mitchell turned to Durowitz.

professor, given the congresswoman’s clarifications. Do you wish to revise your position on any aspects of the bill? His trademark confidence shaken, he replied, I still have constitutional concerns, but I acknowledge that some of my criticisms may have been based on outdated or incorrect information. I’ll need to review the text more closely.

Crockett nodded with grace. I appreciate that, Professor. I’d be happy to share a full analysis showing how each section aligns with constitutional precedent. Perhaps we can agree on protecting every American’s right to vote. Her composed and generous tone underscored the contrast between the two, one clinging to reputation, the other grounded in depth and experience.

As the discussion ended, it was evident to everyone watching that they had witnessed a defining moment, a shift in America’s legal debate where reputation alone no longer guaranteed authority. Within minutes of the CNN segment airing, clips of Crockett’s systematic rebuttal flooded social media.

The most viral moment, her exposing Durowitz’s mention of a non-existent section 502 hit over a million views within an hour. Crockett clapback and D wrong section 502 trended nationwide. Commentators from all sides reacted. Conservative legal analyst Andrew McCarthy tweeted, “Regardless of your stance on the bill, Crockett just gave a masterclass in preparation.

” Durowitz brought generalities. She brought specifics. MSNBC host Rachel Matto opened her show that night, remarking, “We just witnessed the legal version of David defeating Goliath.” Only this time with surgical precision instead of a slingshot. Behind the scenes at CNN, producers who had anticipated a typical policy discussion were rushing to capitalize on what had become the network’s most watched segment of the month.

Overnight, they prepared a special program titled The New Defenders: Rising Voices Reshaping Legal Debate, prominently featuring Crockett in his Manhattan apartment. Alan Dersowitz faced one of the most significant public setbacks of his long career. His phone buzzed endlessly with messages from colleagues, students, and journalists seeking comment.

At Harvard Law, internal message boards erupted with debate over the exchange, with several professors noting that Crockett had used the same Socratic method Durowitz himself once employed to challenge his students. By morning, he released a statement. While I continue to hold constitutional concerns regarding federal election legislation, I recognize Congresswoman Crockett’s strong command of the issue.

Public discourse benefits from wellprepared advocates on every side. Though diplomatic, the statement was clearly seen as an attempt at damage control. For Crockett, the aftermath proved transformative. Her office was inundated with interview requests from major networks, and her social media following tripled overnight.

Recognizing her growing influence, House Democratic leaders invited her to lead a press conference on voting rights legislation the next day. Even more notably, three representatives who had been undecided on the bill contacted her office to express their support. The shift in momentum was unmistakable. What had seemed an unlikely legislative effort now appeared achievable.

Across law blogs and academic forums, analysis flourished. A Yale law professor wrote, “Crockett showed that lived experience paired with legal scholarship can produce a more accurate and persuasive constitutional interpretation than abstract theory alone.” Georgetown Law soon announced a panel discussion titled Credentials Versus Substance: Rethinking Legal Authority in public discourse.

Civil Rights Organizations quickly built on the moment. The NAACP and the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law issued statements emphasizing how Crockett’s arguments reaffirmed the Constitutional Foundation for Federal Voting Protections. Activists in Georgia, North Carolina, and Arizona reported surges in volunteer signups for voter education drives, many citing Crockett’s passionate defense as their inspiration.

Conservative media worked to redirect the narrative. Fox News host Laura Ingram argued that Crockett’s reference to section 502 didn’t address broader constitutional issues. Yet, even on Fox, legal commentators admitted that Dersowitz had been outperformed on substance. He relied on reputation while she relied on preparation, acknowledged former judge Andrew Npoleano.

3 days after the CNN segment, an unexpected development occurred. Alan Dersowitz requested a private meeting with Congresswoman Crockett in her Capitol Hill office. The seasoned attorney arrived alone without cameras or staff. Congresswoman, he began, his tone notably different from their on-air encounter.

I’ve reviewed the bill thoroughly. While I still have concerns about specific provisions, I must admit your constitutional reasoning was largely sound, he paused, then added. And your point about real world impact was well taken. Theory without application holds little value. Crockett, gracious in victory, invited Durowitz to co-author an op-ed discussing their shared principles on voting rights while recognizing their differences in approach.

The public deserves to see that constitutional interpretation doesn’t have to be partisan, she suggested. After reflection, he agreed. Their joint piece in the Washington Post titled Finding Constitutional Common Ground on Voting Rights went viral, this time for promoting meaningful dialogue across generations and ideologies.

It concluded, “When debate centers on substance over status, on evidence over authority, democracy thrives.” For Jasmine Crockett, the debate with Duroitz marked a pivotal moment, not only in her congressional career, but in her broader mission to elevate essential issues. In the week following the CNN appearance, she received invitations to speak at Harvard, Yale, and Howard Law.

Enrollment in voting rights courses surged nationwide the following semester. Perhaps most meaningfully, Crockett received thousands of messages from young lawyers, law students, and especially women of color in the legal field who saw her as a symbol of intellectual courage. “You showed us we don’t have to minimize our experiences to face power,” wrote a second-year law student from Michigan.

“In Washington, the political effects continued to unfold.” Three Republican senators reached out to discuss potential compromise legislation on early voting standards. Though policy differences persisted, the discussion shifted from constitutional theory to practical solutions, an area where Crockett excelled.

At a Congressional Black Caucus meeting, Congressman James Klyurn told her, “You didn’t just win a debate. You changed how this issue will be discussed from now on. That’s how lasting change begins.” 6 weeks later, a revised version of the Voting Rights Protection Act passed the House with bipartisan support.

Though its Senate prospects were uncertain, the bill had momentum few expected before Crockett’s viral moment. Analysts credited her with reshaping public understanding of both the constitutional and practical dimensions of voting rights. In the wider media landscape, the Crockett Dersawitz exchange became a case study in the evolving meaning of authority in public dialogue.

Credentials still mattered, but they no longer overshadowed preparation and lived experience. A new generation demanded recognition, not for their affiliations, but for their insight and rigor. For viewers nationwide, the confrontation provided a rare moment of genuine intellectual engagement on live television.

It transcended party lines and highlighted something deeper, the continuing national conversation about who truly has a voice in democracy, both at the ballot box and in public discourse. Reflecting later with her team, Crockett said, “This was never about embarrassing Professor Durowitz. It was about ensuring every voter’s right to participate in democracy is protected through both constitutional interpretation and real world practice.

When legal theory meets lived experience, that’s where justice begins. The Crockett Dersawitz exchange would go on to be studied in communications, law, and political science programs nationwide. A clear example of how preparation, expertise, and moral conviction can challenge established authority.

It reminded the country that in a healthy democracy, ideas must stand on their own merits, not on the titles of those presenting them. As the debate over voting rights continued across America, one thing became undeniable. A new voice had permanently entered the national stage, proving that the strongest answer to attempted humiliation is confidence, preparation, and courage.

If you found this breakdown of the Crockett Dersawitz confrontation insightful, don’t forget to like this video and subscribe to our channel. We bring you the most significant political exchanges and explore their impact on America’s evolving political landscape. Tap the notification bell so you never miss our latest analysis of the rising voices.

News

“Don’t Leave Us Here!” – German Women POWs Shocked When U.S Soldiers Pull Them From the Burning Hurt DT

April 19th, 1945. A forest in Bavaria, Germany. 31 German women were trapped inside a wooden building. Flames surrounded them….

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft DT

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory in Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

Inside Ford’s Cafeteria: How 1 Kitchen Fed 42,000 Workers Daily — Used More Food Than Nazi Army DT

At 5:47 a.m. on January 12th, 1943, the first shift bell rang across the Willowrun bomber plant in Ipsellante, Michigan….

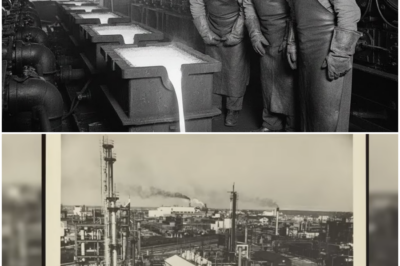

America Had No Magnesium in 1940 — So Dow Extracted It From Seawater DT

January 21, 1941, Freeport, Texas. The molten magnesium glowing white hot at 1,292° F poured from the electrolytic cell into…

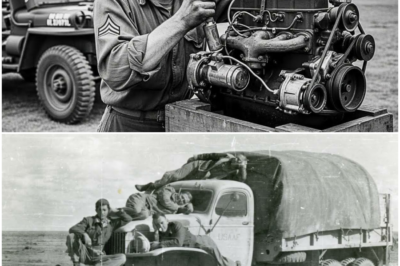

They Mocked His Homemade Jeep Engine — Until It Made 200 HP DT

August 14th, 1944. 0930 hours mountain pass near Monte Casino, Italy. The modified jeep screamed up the 15° grade at…

Beyond the Stage and the Stadium: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Unveil Their Surprising New Joint Venture in Kansas City DT

KANSAS CITY, MO — In a world where celebrity business ventures usually revolve around obscure crypto currencies, overpriced skincare lines,…

End of content

No more pages to load