May 31st, 1943. Oakidge, Tennessee, a rural valley in the Appalachian Foothills. Surveyors break ground on what appears to be just another wartime factory. But these men don’t know they’re standing on the future site of the world’s largest building. A structure so massive it would cover 44 acres under one roof.

a half mile long factory shaped like a giant letter U that would consume more electricity than entire cities. And here’s the contradiction that makes no sense. They’re about to build this colossus to separate something you can’t even see. An invisible difference between two atoms. A difference so minuscule it would take 3,000 stages of machinery, each one no more effective than the last, to amplify it into something useful.

The engineers knew the math was brutal. Each stage of gaseous diffusion only enriched uranium by 4/10 of 1%. That’s 0.0043. To get from natural uranium at 7/10% uranium 235 to 90% weaponsgrade material would require a cascade so enormous it defied imagination. But what they didn’t know yet was that building the structure would be the easy part.

The real nightmare was hiding inside those 3,000 stages. A microscopic barrier that nobody had figured out how to manufacture. A barrier so delicate that five chemists had already failed to create it. A barrier that without a breakthrough in the next six months would render their massive factory completely useless. This is the story of K25, the most expensive gamble of the Manhattan project and the engineering miracle that almost didn’t happen.

Let’s rewind to 1940. Scientists at Columbia University had confirmed what physicist Neils Boors suspected. Only uranium 235 could sustain a nuclear chain reaction, not the far more common uranium 238. The problem was mathematical torture. Natural uranium contains 99.28% 28% uranium 238 and only 0.714% uranium 235.

That’s roughly one atom of uranium 235 for every 140 atoms of uranium 238. And here’s why that’s an engineering nightmare. These two isotopes are chemically identical. They behave the same way in reactions, bond with the same elements, respond to the same processes. The only difference is mass. Three neutrons, a difference of less than 1.3%.

By 1941, the Manhattan project was pursuing three different methods simultaneously. The Y12 plant used electromagnetic separation with calotrons, giant mass spectrometers that could physically separate uranium ions by mass. The S50 plant used thermal diffusion, exploiting how molecules move differently at various temperatures.

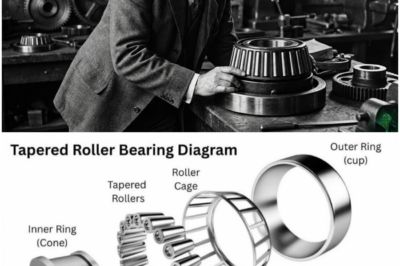

And then there was K25, the gaseous diffusion method. The principle was elegant, almost beautiful in its simplicity. convert uranium into uranium hexafflloride gas. Push that gas through a microscopic porous barrier. The lighter uranium 235 molecules moving slightly faster would pass through the barrier marginally more often than the heavier uranium 238 molecules.

Marginally, that’s the key word. The mathematics based on Graham’s law of eusion showed that each stage could only achieve a separation factor of 1.0. 0043 less than half a% enrichment per stage. To get from.7% to 90% uranium 235 would require 4,000 to 5,000 stages in series. Each one feeding into the next, each one building on the infinite decimal enrichment of the stage before.

The engineers at Kell Corporation, a subsidiary created by MW Kellogg specifically for this secret project, understood they were designing something unprecedented. A cascade of 3,000 plus stages that would operate continuously under pressure, handling one of the most corrosive substances known to chemistry. But what they couldn’t foresee in 1942 was the single problem that would nearly cancel the entire project, the barrier.

By August 1943, construction workers were already pouring concrete foundations in Oakidge. The building steel frame was rising, but Brigadier General Leslie Groves, director of the Manhattan Project, was preparing to cancel K25 entirely. The barrier problem was existential. Here’s what they needed. A porous membrane with millions of microscopic holes.

Each hole precisely sized between 10 and 100 nanome. Small enough to create a diffusion gradient large enough to let gas molecules pass through without clogging. The barrier had to withstand internal pressure of 15 to 30 lb per square in while remaining porous. It had to resist corrosion from uranium hexafflloride, one of the most aggressive chemical compounds ever handled industrially.

And it had to maintain these properties across thousands of square ft of surface area, operating continuously for years. No one had ever created anything like it. Edward Norris, an English interior decorator who had developed fine metal mesh for spray guns, teamed up with Edward Adler from the City College of New York.

Their electroplated nickel barrier showed promise. But as testing progressed through 1943, the Norris Adler barrier revealed fatal flaws. It was brittle, prone to microscopic tears that would destroy the separation efficiency, and it degraded rapidly under operating conditions. Foster Nicks at Bell Telephone Laboratories tried a different approach using powdered nickel compressed and centerined into a porous material.

His barriers were stronger but inconsistent. Some samples worked beautifully, others were too dense, blocking gas flow entirely. By summer 1943, the Special Alloid Materials Laboratories at Columbia University, led by Harold Yuri, had tested dozens of designs. The failure rate was devastating. In some test batches, 95% of barriers were unusable. The math was unforgiving.

K25 would require over 3,000 barriers, each roughly 6 ft in diameter. If even 5% failed during operation, the entire cascade would lose separation efficiency. The plant would produce nothing useful. But what they didn’t know was that the solution was being developed 40 mi away in Bound Brook, New Jersey.

Frasier Grath and his team at the Balyte Corporation, a Union Carbide subsidiary, had been experimenting with nickel barriers independently. They believed Bell Labs wasn’t using the latest techniques. Working with Clarence Johnson at Kellogg’s Jersey City Laboratory, they developed what became known as the Johnson barrier. This barrier combined the best aspects of both previous designs.

Powdered nickel was processed using chemical techniques that created uniform pore sizes. The material was stronger than the Norris Adler mesh but more consistent than the Nyx powder barriers. On October 1943, Keith proposed switching the entire project to the Johnson barrier. Harold Yuri balked. His team had spent 18 months developing the Nors Adler design.

Switching now would require new production facilities, new training, new everything. On November 3rd, 1943, Groves made his decision. Develop both barriers in parallel. Whichever showed better quality by January would become the production standard. But here’s the incredible part. Even with the Johnson barrier decision, they still had to solve the production problem.

January 16th, 1944, Groves ruled in favor of the Johnson barrier, but ruling and manufacturing are entirely different problems. Edward Mack Jr. at Columbia University created a pilot production plant inside Shmerhorn Hall, a university building in Manhattan. Clarence Johnson built another at the Nash building on Broadway, a former automobile dealership converted into a top secret laboratory.

The real breakthrough came when Groves did something audacious. He approached the International Nickel Company and acquired 80 short tons of pure nickel using the Manhattan Project’s overriding priority. In wartime, with nickel being a critical material for armor and artillery, this was essentially commandeering a national resource.

With abundant nickel, both pilot plants ramped up production. By April 1944, they were producing acceptable quality barriers at a 45% rate. Still not great, but improving weekly. Meanwhile, in Oakidge, construction was proceeding on a structure that defied belief. The K25 building was designed in a U-shape with each wing extending nearly a/4 mile.

The structure was four stories tall, constructed with a steel framework that required 65,000 tons of steel beams. For context, that’s enough steel to build 10 large naval destroyers. At the height of construction in May 1944, over 25,000 workers swarmed the site. JA Jones Construction Company from Charlotte, North Carolina, managed the primary construction.

More than 60 subcontractors handled specialized work. These workers knew nothing about atomic weapons. They were told K25 was producing material for a new type of explosive. Most believed it was related to conventional ordinance. Security was absolute. Armed guards patrolled continuously. Workers lived in a temporary city called Happy Valley, housing 15,000 people in prefabricated barracks and trailers.

The construction itself presented extraordinary challenges. First, the foundation. Oak Ridge sits on Appalachian bedrock, but the K25 site required excavating 30 to 40 ft down in places. They poured more than 100,000 cubic yards of concrete. That’s enough concrete to build a highway from downtown Oakidge to Knoxville.

Second, the diffusers. These were the cylindrical containers, each about 6 feet in diameter and 12 feet tall, that would house the barrier and contain the uranium hexaflloride gas under pressure. They needed 3,000 of them. Groves contracted Chrysler Corporation to build these diffusers. Chrysler President KT Keller assigned Carl Hner, an electroplating expert, to figure out how to nickelplate objects that large.

The special alloid materials laboratories had tried and failed. Nickel plating required the object to be submerged in electrolyte solution while electric current flowed through it. Hner discovered the key was eliminating oxygen contact during the multi-step pickling and scaling process. Chrysler’s entire Lynch Road factory in Detroit was converted to diffuser production.

The electroplating process required over 50,000 square ft of floor space and thousands of workers operating in carefully filtered air. By war’s end, Chrysler had manufactured and shipped 3,500 diffusers to Oakidge, each nickelplated to resist uranium hexaflloride corrosion using 1,000th the nickel that a solid nickel diffuser would require.

Third challenge, the compressors. Each diffusion stage required a pump to maintain gas pressure and move uranium hexaflloride through the cascade. These weren’t ordinary industrial pumps. They needed to handle gas 12 times denser than air. They couldn’t leak, not even microscopic amounts. Any leakage of enriched uranium hexaflloride would waste the entire enrichment process up to that point.

Ingresol Rand initially took the contract then backed out in early 1943 saying it couldn’t be done. Clark Compressor and Worththington Pump both refused. Keith and Groves met with Alice Chmer’s executives. Alice Chomemers agreed to build a completely new factory to produce pumps for a design that didn’t yet exist.

That’s the level of commitment required. The breakthrough came from Judson Swearing at the Elliot Company. He designed a centrifugal pump with revolutionary shaft seals that could contain uranium hexafflloride gas while operating at compression ratios of 2.3 to 3.2:1. Alice Chomemers manufactured these pumps.

By late 1944, they were producing 300 pumps monthly. But what they didn’t know yet was whether all these pieces would actually work together. April 1945, the first sections of K25 became operational. Engineers had installed 540 diffusion stages in the initial section, even though acceptable barriers weren’t yet available for all converters.

They ran tests using substitute barriers just to verify the cascade design. The engineering complexity was staggering. Each stage consisted of a converter containing the barrier, a centrifugal pump and connecting piping. The uranium hexafflloride entered at the bottom of each stage was pushed through the barrier by pressure differential and the slightly enriched gas moved to the next stage while the depleted gas cycled to the previous stage.

Temperature control was critical. Uranium hexaflloride sublimes at 133.7° F. Below that temperature, it solidifies and would clog the entire cascade. Above certain temperatures, it becomes too corrosive. Engineers maintained temperatures within a 5° range across all 3,000 stages. The building required its own power plant.

KEX engineers initially relied on 10C Valley Authority electricity but convinced Groves to build a dedicated power station. This wasn’t paranoia. A power failure would force the entire cascade to shut down. Restarting would take weeks as operators carefully brought each stage back to operating temperature and pressure.

The K25 power plant constructed on the Clinch River generated variable frequency electricity specifically for the gaseous diffusion compressors. This eliminated the need for complex transformers and provided redundant power circuits. By August 1945, K25 was producing enriched uranium, though not to weapons grade.

The plant operated as intended, enriching uranium from 0.7% to approximately 20% uranium 235. This partially enriched material then fed into the Y12 electromagnetic plant for final enrichment to 90% weapons grade. The uranium used in Little Boy, the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6th, 1945, included enriched uranium from K25’s initial production runs.

But the real vindication came after the war. In 1946, K25 achieved the capability to produce highlyenriched uranium without requiring Y12’s final enrichment. The barrier problem had been solved. The cascade design worked. Between 1946 and 1964, four additional gaseous diffusion plants were constructed at Oak Ridge, K27, K29, K31, and K33.

The Oak Ridge gaseous diffusion plant became the United States primary source of enriched uranium throughout the Cold War. K25 operated continuously until August 27th, 1985. During 40 years of operation, it enriched uranium for thousands of nuclear weapons and provided fuel for civilian nuclear power plants.

The final cost of K25 was $512 million in 1945. That’s approximately $8.5 billion in today’s currency. It was the single most expensive component of the Manhattan project, costing more than the entire Hanford plutonium production site. The engineering solutions developed for K25 created entire industries that didn’t exist before.

The nickel barrier technology pioneered by Fraser Grath and Clarence Johnson led to advanced filtration membranes used in industrial chemistry, water purification, and even medical dialysis equipment. The principle of using microscopic pores to separate molecules by size became foundational to membrane technology. The Chrysler electroplating process developed by Carl Hoistner revolutionized metal finishing for large industrial components.

Modern gas turbines, chemical reactors, and aerospace components used descendants of that technology. Judson Swearen’s centrifugal pump design influenced decades of industrial compressor development. His shaft seal design solved problems that had plagued engineers for generations. But perhaps the most significant impact was organizational.

K25 proved that impossibly complex engineering projects could be executed under impossible timelines through parallel development. When the barrier problem threatened cancellation, Groves didn’t pick one solution. He funded multiple approaches simultaneously, accepting that some would fail, betting that at least one would succeed.

This became the template for cold war weapons development, the Apollo program, and modern rapid prototyping in Silicon Valley. When you can’t afford to wait for perfect information, develop multiple solutions in parallel and select the winner when results come in. The gaseous diffusion method pioneered at K25 remained the world’s dominant uranium enrichment technique until the 1990s when gas centrifuge technology finally surpassed it in efficiency.

For 50 years, every nuclear weapon and nuclear power plant in America relied on descendants of that 3000 stage cascade. K25 itself was demolished between 2013 and 2017. The structure was so contaminated with residual uranium that demolition required specialized techniques. Today, the site is the East Tennessee Technology Park, and only a small overlook remains where visitors can see where the world’s largest building once stood.

Here’s why this story matters today. Engineers at K25 solved the problem that five separate research teams said was impossible. They built production facilities for a barrier design that hadn’t been proven to work that constructed the world’s largest building while the technology it would house was still being invented.

Modern engineers face similar impossible problems. Battery technology for electric vehicles. Carbon capture for climate change. Quantum computing error correction. The lesson from K25 isn’t the genius solved everything. It’s that systematic parallel development, adequate resources, and willingness to accept partial failures created breakthrough success.

The barrier problem shows us something profound about innovation. The solution didn’t come from the most prestigious laboratory. Bell Labs failed. Columbia University’s top chemists struggled. The breakthrough came from Balyte Corporation researchers in New Jersey who weren’t even supposed to be working on barriers.

collaborating with an engineer at Kellogg who recognized how to combine different approaches. Innovation happens at intersections, between disciplines, between organizations, between people who weren’t supposed to solve your problem but did anyway. And here’s the final lesson. K25 worked because engineers built the cascade before they perfected the barrier. And that sounds backwards.

It is backwards, but it’s also brilliant. By the time Johnson’s barriers were ready for production in mid1 1944, the building existed, the diffusers were installed, and the compressors were tested. The barriers were the last piece, not the first. Today, we call this concurrent engineering.

We think it’s modern management theory. But engineers in 1943 Oakidge were already doing it, driven by wartime necessity. So, if you enjoyed learning how Manhattan project engineers built a 44 acre factory to separate invisible differences between atoms, hit that subscribe button because we’re going to explore more stories of technical problem solving that changed history.

Next week, we’re looking at Operation Pluto, the secret underwater fuel pipeline that supplied Allied armies after D-Day. Engineers laid 17 pipelines across the English Channel while German forces controlled the coastline. How did they do it without being detected? How did they keep fuel flowing under the channel bed through winter storms? The engineering is absolutely fascinating.

But what really makes K25 remarkable isn’t the size of the building. It’s the size of the gamble. General Groves authorized $512 million based on laboratory experiments that hadn’t been proven at scale. Engineers built 3,000 stages knowing that if the barrier didn’t work, the entire cascade would be worthless. That’s not just engineering.

That’s faith in human problem solving capacity. That’s belief that if the laws of physics permit something, engineers will figure out how to build it. And they did.

News

How a US Soldier’s ‘Payload Trick’ Killed 25 Japanese in Okinawa and Saved His Unit DT

At 0330 hours on April 13th, 1945, Technical Sergeant Bowford Theodore Anderson stood inside a tomb carved from Okinawan limestone….

Jimmy Fallon SPEECHLESS When Keanu Reeves Suddenly Walks Off Stage After Reading This Letter DT

Keanu Reeves finished reading the letter, lifted his head, and without saying a single word, walked off the stage. 200…

They Said One Man Could’nt Do It — Until His Winchester Model 12 Killed 62 Japanese in 3 Hours DT

At 11:47 a.m. February 19th, 1945, Vincent Castayano crouched in volcanic ash on Ewima, gripping a Winchester Model 12 shotgun…

Kevin Costner & Jewel CAN’T Hold Back Tears When 7-Year-Old’s SHOCKING Words Stop Jimmy Fallon DT

Three words from a seven-year-old boy changed late night television history forever. But it wasn’t just what little Marcus said…

Jimmy Fallon STOPS His Show When Keanu Reeves FREEZES Over Abandoned Teen’s Question DT

Keanu Reeves froze mid- interview, walked into the Tonight Show audience, and revealed the childhood pain he’d carried for decades….

What Javier Milei said to Juan Manuel Santos… NO ONE dared to say it DT

August 17th, 1943, 30,000 ft above Schweinfort, Germany, the lead bombardier of the 230 B17 flying fortresses approaching Schweinford watched…

End of content

No more pages to load