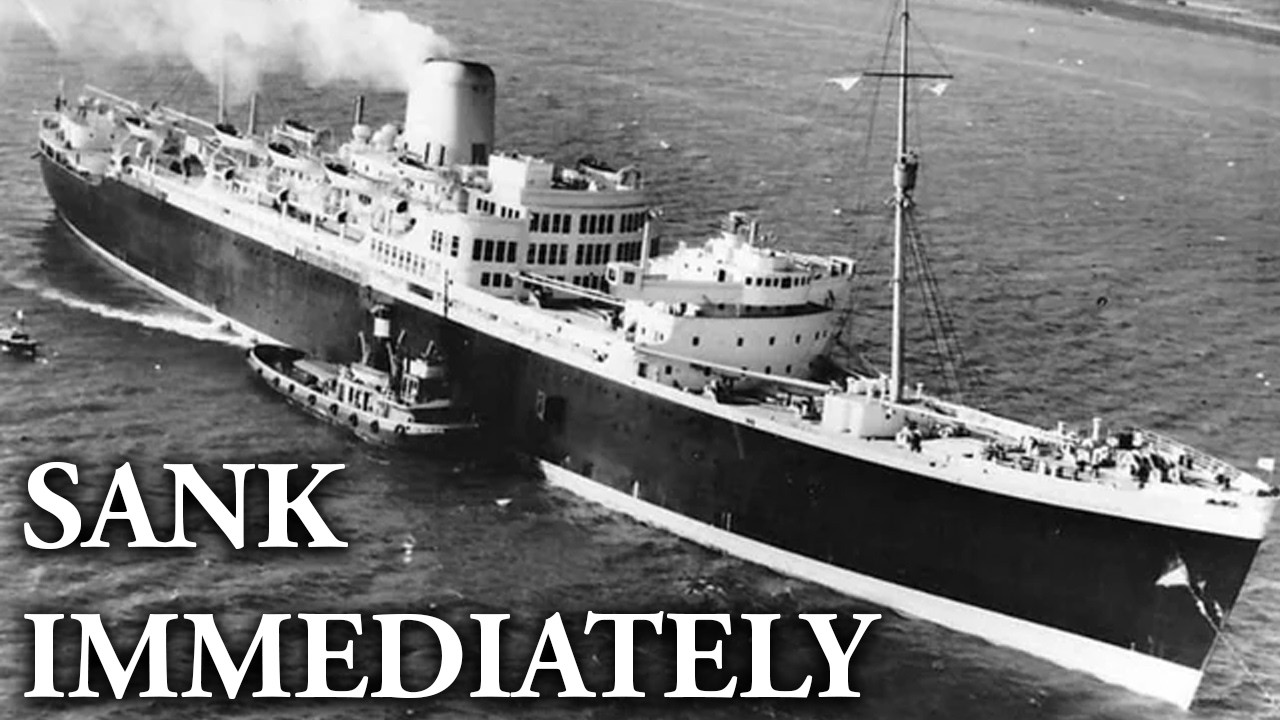

A ship owned by the White Star Line is about to set off on its first voyage. It’s big for its time, advanced and modern, it carries hundreds of hopefuls for new lives overseas. But then tragedy, a sudden blow, sees the big ship sink, taking hundreds of souls with her.

If this story sounds familiar, and it probably should, then it may surprise you to know I’m not actually talking about Titanic. I’m talking about another ship, the Taylor, which was lost on its maiden voyage back in 1854. On the big passenger ships in the 1890s through the 20s and beyond, the first trip on a new ship, that is the maiden voyage, as it was known, was usually under booked while the company ironed out all the kinks. And perhaps for good reason.

A lot of ships have set out on their very first voyage only to meet disaster and sink. From White Starline’s very first Titanic moment to the ultramodern Danish ship that simply disappeared, the magnificent French passenger liner that burnt like a torch, and the brand new luxury vessel that broke in half. These are the ships that sunk on their very first outings.

Ladies and gentlemen, I’m your friend Mike Brady from Ocean Liner Designs, and these are the ships that were lost on their maiden voyage. It’s the early 1850s and the papers are a buzz with news of the gold rush in Australia. Gold fever was spreading rapidly worldwide.

Demand for quick passage to Australia was huge and growing by the day with thousands eager to seek their fortune far across the oceans. Keen to meet this need and quickly, the White Star Line chartered the passenger sailing ship Taylor built for Charles Morren Company in Warrington Liverpool in 1853. Designed by William Renie.

Her lightning fast construction saw her launch on the 5th of October, only 6 months after her keel had been laid. The ship had capacity for 4,000 tons of cargo and could carry 650 passengers, displacing 1750 tons, that’s 230 ft and 70 m in length. She boasted the title of being the largest iron sailing merchant ship of her time. A state-of-the-art fullyrigged iron clipper, the Taylor was built with speed and luxury in mind.

Her iron hull was still a relatively new concept, representing the beginning of a gradual evolution away from the typical centuries old timber construction. Supposedly safe in the knowledge that the Taylor was touted as not only one of the biggest and fastest vessels of her time, but also as a safer and more comfortable option to make a voyage to the southern hemisphere.

Passengers jumped at the chance to travel on board. But although she certainly appeared impressive, beneath that dazzling exterior lurked unnoticed issues born of her hasty completion. Issues that would become all too apparent as she set out on her maiden voyage.

In a time before radar, 19th century sailors were much more reliant on visual indicators for navigation, like tracking celestial bodies, stars and planets, and land masses. The huge flaw in that approach, of course, was that in cases of low visibility, like storms and fog, those visual clues were impossible to keep track of. Instead, they’d have to rely on their compasses.

The Taylor had three. That was standard. But the problem was that no one had considered how her modern iron hull might interfere with the compass readings, something that would very much come back to bite them. Adding to the Taylor’s flaws, the Clippers three masts were positioned more widely apart than was standard, leading her to be difficult to handle.

Not helped at all by the fact that her ropes hadn’t been seasoned correctly, causing them to be excessively slack. On top of that, they were too thick to pass easily through the pulleys and blocks, meaning that the rigging, and therefore the sails were made to be incredibly difficult for the crew to control.

The final nail in the coffin was that the tailor’s rudder was markedly unders sized compared to her tonnage, affecting her maneuverability even more. Had the tailor undergone sea trials, it’s likely that these issues would have been recognized and potentially rectified before setting sail. But instead, she would embark on her maiden voyage untested.

The ship’s captain, John Noble, was reliable and respected, but young, just 29 years old. In fact, he was of record-breaking repute, having previously set a crossing speed record on the same route from Liverpool to Australia. This time, though, the trip was marked by an ill omen before it even began.

Prior to the Taylor’s launch, Captain Noble fell from a significant height into the ship’s hold, seriously injuring himself in the process. The rest of the 70 odd crew consisted mostly of inexperienced stewards. Newspaper reports would later claim that they themselves were there for the purpose of seeking passage to Australia. Many also couldn’t speak English, so it was difficult for the crew to actually communicate with each other. Not exactly an ideal setup.

Despite these difficulties, on the 19th of January 1854, the Taylor would begin her maiden voyage from Liverpool, England, bound for Melbourne, Australia. Waved off by cheering crowds, an atmosphere of hope and excitement undoubtedly must have surrounded the vessel as these prospecting dreams of far-off gold and anticipated fortune drew nearer.

The passengers settled in for what was expected to be a lengthy, though speedy for the time, if you can believe it, 3monl long journey to the other side of the world. It was noted as they set off along the river Mury that day that each of the ship’s three compasses were giving different readings.

Troubling for sure and a bit of a red flag, but nevertheless, they continued on. Just two days into a voyage, the Taylor would run into trouble. Buffeted by rough weather and with visibility waning, the small and inexperienced crew found themselves struggling to maintain control of their ship. Unbeknownst to those on board, they were straying significantly from their intended course.

with dense fog preventing this from being realized until it was far too late. Under the impression they were heading southward, they were instead moving rapidly west straight towards Ireland. At around 11:00 a.m. the 21st of January, through the winintry gloom of the morning, a shocking and unwelcome sight loomed into view.

Instead of the open water of the Irish Sea, directly ahead was a foroding wall of dark cliffside. Prevailing southwesterlys had pushed the ship off course northwards towards Lambeay Island, 5 km off the coast of Ireland. Both of the main anchors were hastily dropped as soon as land was sighted. But it was no use.

Their chains snapped and the Taylor smashed straight into the cliffs off Lambbee’s northeastern coast. Crashing up against the rock face repeatedly, the ship was at the mercy of the forceful storm. There was an attempt to lower one of the ship’s lifeboats, but the big waves took it up and smashed that to pieces on the rocks as well.

The ship’s stern was going quickly and passengers and crew raced up top to escape. Panic had set in almost immediately with people scrambling to try and save themselves. Safety was tantalizingly almost within reach. In fact, the cliffside was so close that the crew opted to deliberately collapse one of the masts, creating a makeshift, if perilous, gang way to the shore.

Dozens of people were able to clamber their way across the mast and make the leap onto dry land. Some carrying ropes with them that provided another invaluable link between the ship and the shore, allowing more survivors to be pulled to safety. The Heraford Times later described how the survivors on shore could perceive the unfortunate creatures struggling amidst the waves and one by one sinking under them.

Anyone who tried swimming to land would then have to endure a strenuous climb up the tower and cliff face equivalent to roughly an 8story building. Those who were left behind climbed to the topmost parts of the rigging in an effort to avoid the rising water.

Captain Noble remained on board right until the end before making the leap across to shore, aided up the steep cliff face by another survivor. The Taylor was then swept off the rocks by a powerful wave and dragged into deeper water. At a depth of just 17 m, the sunken ship still had the tops of her masts poking above the waterline, a crude marker of the horror that had just taken place there.

One of the passengers who’d made it onto the island ran to her nearby home to alert the authorities, but help couldn’t be sent out until the stormy seas had calmed. Some 14 hours after the tailor had met her terrible fate, the last survivor, a man named William Vivers, no doubt exhausted, feeling cold and terrified, was plucked from the top rigging and finally brought to safety.

More than half of those on board would lose their lives despite having at times been close enough to be able to jump to the safety of land. Most of the crew would survive while the majority of the losses were, of course, immigrants who’d been in search of a better life. For the women and children, survival rates were even more grim. Only three of the 100 female passengers would be successfully rescued, and only around 4% of the children on board made it out alive. Around 650 people had been aboard the Taylor, but only 280 would live.

The staggering survival rate of men compared to women can likely be attributed to the heaviness of Victorian women’s clothing, consisting of multiple layers of thick ensemble pieces over increasingly voluminous layered skirts accentuated by heavy krenolines.

Staying afloat while quite literally being weighted down in stormy waters would be way too difficult enough for even a strong swimmer. And since fully submerged swimming was still largely seen as a socially improper activity for a Victorian lady, the ability to swim well was uncommon. To make matters worse, lifeboats were not yet customary. Thankfully, not every child perished in the disaster.

One survivor was the 12-month-old ocean child. An elderly Frenchman was credited with retrieving an infant boy from the wreckage. Said to have held on to the baby with his teeth and swam through the treacherous waters to safety. With no sign of the boy’s parents, the so-called ocean child was then taken under the wing of the local Reverend John Armstrong.

The reverend made a description of the child’s appearance in the papers in the hope he said it may catch the eye of any relative in England. After around a month’s search, the boy was discovered to be Arthur Charles of Heraford and was happily reunited with his maternal grandmother who had made the journey to Ireland to collect him.

When he found out that Arthur’s grandmother was impoverished, the reverend pledged to support the family financially to try to help ensure the boy’s success and recovery. The story drew a fair amount of attention at the time, with little Arthur being the focus of warm and widespread interest, many believing his survival to be the sign of divine intervention.

Some members of the public even travel to visit him. The Heraford Times in 1854 described how from the way in which he clings to those who fondle him, it might be inferred that the horrors of the scene from which he was so providentially rescued have left an impression on his infantile senses.

Four official investigations into the disastrous maiden voyage would occur following the Taylor’s sinking. The Board of Trade questioned Captain Noble for his decision not to take soundings despite the poor visibility, that is to figure out the depth below Keel, especially given that he was found to have been aware that the compasses were in error.

To which he reportedly responded, “I think I did wrong, and this will be a warning to me in the future.” It has been speculated that his previous fall into the hold might have caused a head injury that impaired his judgment. Ultimately though, he was largely absolved of blame and managed to recover his reputation and have his master’s certificate restored.

The White Star Line in turn was criticized for rushing the ship’s launch and neglecting safety standards. Ultimately, the disaster was put down to a combination of unfortunate oversightes with the blame being deflected towards different parties, the captain, the crew, and the White Star Line. The sinking would lead to the shipping company reviewing its safety procedures.

One outcome being the recommendation that immigrant ships should increase the minimum crew requirement. That was a good start. Sometimes referred to as the first Titanic, the similarities between the two disasters are pretty striking. Both were White Starline ships. They were both registered in Liverpool.

And most obviously of all, both were made in voyage disasters with heavy loss of life. The White Star Line that had chartered the Taylor was technically a different company to that which would bring about the Titanic. In the 1860s, after the company had been facing financial difficulties for some time, the original White Star went bankrupt.

At a liquidation sale in 1868, it was Thomas Isme who acquired the company name and logo, and the version of the White Star line that would later operate the Titanic was formed. Their preference for marketing their ships as big, fast, luxurious, and unsinkable remained much the same as when the Taylor was first launched, but it would be the second time that the company would lose a ship on its maiden voyage in 1912.

The Taylor’s wreck was rediscovered in 1959, sitting below the surface, right where she sank off Lampay Island. It’s still possible to dive with a license to the wreck of this ship. An experience that would no doubt be as eerie as it is fascinating.

The chillingly part of the ship’s cargo included a number of unmarked gravestones which reside now on the sea floor at the wreck site. A more dignified memorial to the many lives lost in the form of a Bower anchor salvaged from the Taylor’s wreck was finally erected in Dublin 145 years after the loss in 1999. What has to go wrong for a ship designed for safety, strength, and durability to vanish without a trace on its maiden voyage? The comparisons continue with what is often referred to as Denmark’s Titanic.

Gee, there’s a lot of Titanics out there. Taking place almost five decades after that disaster though the Hans headtoft was supposedly unsinkable but history tells us that’s not the safest claim to make of any ship. The 1950s were a time of great change for Greenland.

The Greenland Commission was keen to expand the island’s economic prospects, improve the living standards for its population, and to address the problems associated with its extreme isolation. With only around 30,000 inhabitants at the time of the Hans headed to’s launch in 1958, it was nevertheless a strategic geopolitical buffer zone that was extremely important between the US and the Soviet Union.

Royal Greenland Trading, the owner of the Hans Headoft, as part of Greenland’s development, established a fleet of small cargo ships to meet the need for supplies and new import opportunities. These ships were capable of carrying a limited number of passengers. There wasn’t need for anything particularly fancy.

Instead, speed and the ability to deliver goods quickly with a focus. Traveling on the seas around Greenland during winter was long deemed too dangerous in that region thanks to the plummeting temperatures, the rough seas, and the prevalence of drifting ice. However, by 1949, the controversial decision was made to maintain a year-round service in Greenland in order to meet growing demand.

Citing recent near misses involving icebergs, the maritime labor unions along with the Danish government opposed this call. but to no avail. The supposed super ship, the Hans Head to was intended to be a built-for-purpose solution to these safety concerns, promising to be a revolution in Arctic navigation.

The order for the ship was placed in 56 by Royal Greenland Trading should be launched 2 years later on August 13th, 1958 in the Friedrich’s half and shipyard in the North Jutland region of Denmark. The 2,857 ton passenger cargo liner was 82.6 m in length. That’s 270 ft and powered by a 2900 horsepower diesel engine. Named for the former Danish prime minister, the Hans headto was built with modernity and safety in mind.

Expenses weren’t spared with the ship’s then state-of-the-art equipment, including Deca navigators, radar, gyro compasses, and radio equipped life rafts. In fact, the Hunts head was plenty prepared for if things might go wrong. As well as its four self-inflating life rafts, the ship also had three metal lifeboats with capacity for 35 people each along with an additional 20man boat.

Built to withstand the icy conditions of the Arctic and the northern Atlantic Ocean specifically, the vessel was fitted with a double bottom reinforced bow and seven watertight compartments intended to help keep her afloat even in the event of an impact. But unlike with other polar ships, the Hans headto was constructed using riveted rather than welded steel plates.

A decision that was also met with skepticism regarding her ability to withstand ice pressure. There was another thing that set the Hans head to apart from your typical merchant ship. Unbeknownst to the public or even the Danish Parliament, the vessel had been designed for easy warship conversion.

The Ministry of Defense had requested that three 40mm anti-aircraft guns could be fitted with reinforcement where the gun’s foundations would be built and an ammunition compartment, all of which was conveniently left off of the ship’s plans. The guns weren’t mounted at the time of the sinking, though. Following test firing, all military equipment was promptly dismantled and stowed in the headto’s cargo hold.

Among the ship’s passengers on that fateful maiden voyage was Algo Luna, Greenland’s leading political figure in the 1950s. He’d been an important advocate for the modernization of Greenland and was the first Greenlander to ever hold a seat in the Danish Parliament elected in 1953. But notably, he was also one of the most vocal critics of the winter passenger sailing initiative, quoted as telling his son that it would take an accident before the government would recognize the risk they were taking with the change. The first part of the headtoff’s journey was actually quite successful. Departing Copenhagen on the 7th of

January 1959, the Hans headtoff was bound for Kakokto, Greenland. A new speed record was set for the crossing. The ship then proceeded to call it several ports along southwestern Greenland, including the country’s capital, Nuke. The captain, Paul Ludvig Rasmusen, had over 20 years of experience sailing on Greenland’s waters, so the passengers were in safe hands.

Returning again to Kakokto a final time on the 28th of January, the Hans headto would begin to make her way back to Copenhagen around 9:15 the morning of the 29th. She was at near full capacity with 55 passengers, including women and children, 40 crew members.

In addition to this, she was carrying precious archival material in the form of parish genealological records and grinlandic history destined for preservation in the Danish archives along with a slightly less impressive cargo of frozen fish. Around 24 hours later, Captain Resmusen radioed that the ship had encountered a fierce snowstorm.

Visibility was so poor, only one nautical mile, that they decided to reduce speed down to 8 knots. For a while, it seemed like things were clearing up. Visibility had improved enough for them to now be able to identify surrounding ice flows, and by 11:00 a.m., they’d increase their speed back up to 13 knots. But then, just 24 minutes after the ship had sent out that update to say all was going well, an SOS was transmi

tted. It seemed that the brief calm hadn’t lasted. At 1:56 p.m., the shocking news came in. The Hans headto had struck an iceberg around 65 km due south of Greenland’s southernmost point, which had torn a gash deep into the port side of the ship’s riveted steel hull. The distress call was answered by the United States Coast Guard cutter, the Campbell, as well as the Johannes Cruz, a West German fishing troller who was around 25 nautical miles east of the headtoff’s location.

Braving the terrible weather conditions, they both set off to assist as quickly as possible. Challenged by the low visibility caused by snow squalls and struggling against the merciless stormy seas, waves reached towering heights up to 20 ft, around 6 m, and there was ice everywhere.

Around an hour later, a follow-up message stated that the engine room was rapidly flooding along with the plea, “We have many passengers on board.” Over in Newfoundland, Canadian and US rescue aircraft were grounded due to harsh weather. However, another German fishing troller also bravely began to make their way to the headtoft. Maintaining consistent communication with the ship, the Johannes Cruz was drawing closer.

But something seemed to be off with the position that the founding ship had given. Flares were sent up, but the Johannes Cruz was unable to see them. Nor was the Hans Headtoft able to see any signs of the trollers search lights. Carl Dalberg, the ship’s radio operator, would remain at his post, calmly sending out calls for help until the very end.

At 5:41 p.m., the last complete message from the ship crackled through, slowly sinking, it said, and need immediate assistance. Roughly 4 hours since the first distress call, one final disjointed message was seemingly picked up by the Johannes cruise, interpreted as something like, “We are sinking now.

” Then all communication was lost. All attempts to reestablish contact went unanswered. Only a few months after her launch, the ship had been lost to the sea, some distance off the coast of Cape Farewell. Curiously, it seems that none of the ship’s multiple lifeboats were used during the sinking at all.

It’s unclear exactly why this is, though it’s safe to assume that it would probably have been incredibly difficult to deploy them safely given the big seas. Perhaps they believe that help was close enough it would be better to not attempt a risky evacuation. After all, with water that cold, it would be unlikely that anyone would survive any more than 60 to 120 seconds of exposure.

Rescue ships converged on the area. Relatives of those on board crowded around their radios at home, desperate to hear any news of what was happening. The Johannes cruise may potentially have reached the last known location of the Hans headto just minutes after she sank beneath the surface.

An intensive search took place over the next week coordinated by the Greenland command at the Groonadale Naval Station. 16 ships of different nationalities along with the United States and Canadian aircraft all assisted the rescue operation, but they were unfortunately unsuccessful. There was simply no sign of the Hard’s head or any of her passengers anywhere.

On the 7th of February, the search was reluctantly called off. The ship and all who’d been aboard were declared lost. The shock of losing yet another unsinkable state-of-the-art ship that was supposed to have been purpose-built to withstand the very conditions that took it down rippled through local media.

In the wake of the loss of Algo Luna and the other 94 men, women, and children who perished in the sinking, the Danish government found itself facing a political scandal. The dangers of sailing during Greenland’s punishing winter months had been raised many times in Parliament. Johannes Sherbel, then Greenland’s minister, had been one of the main supporters of the idea.

After the sinking, he was threatened with impeachment, accused of pressuring the captains of the Royal Greenland trade to sign off on their approval of winter sailings, an approval that he used as an instrumental part of his fight to make the sailings a reality. Critically though, it was found that the captains had previously written a statement unanimously advising against the decision to sail during winter with passengers. A statement that the minister claimed to have been unaware of despite evidence that he had known of

the statement after all. Investigations concluded he had not deliberately attempted to mislead the parliament. So, he was able to maintain his position. Though he escaped impeachment, his legacy was forever tarnished. The disaster was also a huge loss for Greenland, both in the literal sense, thanks to the tragic perishing of so many Greenlandic citizens, but also the loss of 16 tons of irreplaceable genealological records. This was around a third of Greenland’s total archival material, covering everything from the

region’s trade to the population’s health status dating back as far as 1780. A key piece of that land’s heritage and cultural history had gone down with the ship. As response to the outcry as well as the safety concerns surrounding winter passenger sailings, the Danish government made the decision to reopen a decommissioned military airfield at Greenland so that airline services could replace winter sailings.

New safety regulations were put in place and efforts were made to improve the efficiency of the region sea rescue services as well. Shortly after the sinking, a fund known as the Greenland Foundation of 1959 was established in an effort to compensate the families of those who were lost.

Controversially though, a significant amount of the collected funds were never actually distributed or even used at all. 46 years after the disaster, a memorial plaque featuring the names of the lost was dedicated at a ceremony in 2005 attended by Queen Margarita. You can still see it today at the North Atlantic House building in Copenhagen, Denmark.

What exactly happened to the MS Hardoft along with the location of her wreck is still something of a mystery. We know she hit an iceberg, but hardly a single trace of her was ever found. No survivors, floating debris. The only physical remnant of the ship was a life ring found washed up on the coast of Iceland 9 months after the sinking.

It remains on display in the Church of our Savior in Kokto, Greenland. To this day, the Han’s head to remains the last known shipwreck with casualties to have been caused by collision with an iceberg. It’s 1:30 a.m. 16th of May 1932 and the day of Pentecost celebrations aboard the MS Gor Filipar is just wrapping up.

Many passengers are already peacefully asleep and the final stragglers from the party make their way back to their cabins. Madame Valantang on returning to her first class cabin notices a strange acred smell like burning rubber filling the corridors along Ddeck. Accompanied by this comes an unidentified but ominous crackling noise. Later, an alarming SOS message is received. Fire has broken out on the ship and it’s spreading rapidly.

The luxurious new addition to the Majeria Maritine fleet on her maiden voyage is going down in flames. Launched in November 1930, the Shores Filipar was a 17,359 gross registered ton liner built by Attelier Esantier Deoir in Sandazair. the legendary West Coast shipyard. Going against the French sailor’s superstition that to name a ship after a living person was bad luck and perhaps going on to prove it right.

The MS Gor Filipar was named for the French ship builder and then CEO of the company Majeri Maritim. Following the first world war, Attelier Shantier de la no longer receiving big orders for new warships was instead looking to focus their efforts on building merchant ships. They had a very good reputation and there was demand for fast comfortable ocean liners that they were keen to meet.

They landed an order with the Netherlands line and built the MS Peter Cornelius soon. All was not well though. The construction faced many problems, not the least the thing catching fire twice in the shipyard. Originally expected to be completed by January 1926, a significant delay was incurred when the flames broke out, causing substantial damage that would take around a year to repair. Then in November 1932, the ship would be lost completely again to fire.

It was in the 1930s that electricity aboard ships had begun to be featured more extensively and the Gor Filippar was no exception to this. She had plentiful light fittings throughout along with electric ovens and appliances in the kitchens.

The ship’s power grid was fed by high voltage direct current and this along with her two diesel Sultza engines made her the height of modernity. Aside from her technical achievements, the Gor Filipar was fitted with exquisite interior decoration, particularly of course in first class. The ship’s walls were beautifully wood panled featuring ornately carved embellishments. Plush wall hangings adorned its many public rooms. Carpeting trimmed the floors and electric powered chandeliers hung from the ceilings.

There was a grand staircase and a rich varnished timber. And passengers had access to a lavishly decorated smoking room, a traditionally styled bar, tennis court, and even a large classical Roman swimming pool complete with columns, marble arches, and ornate wall art. The Gor Filipar had itself been built to replace another ship that had interestingly caught fire, the Paul Lar, which burnt up while in dock back in December 1928.

Yet, this new ship too seemed to be plagued by fire right from the start. During construction, a short circuit would lead to flames breaking out in the Gor Filipar’s refrigerated holds. The one stroke of luck in the ship’s unfortunate start had been that more substantial financial losses were avoided, as most of the luxury fittings had not yet been installed at the time of the fire.

The very unfortunate pattern, though, seemed to be establishing, one that would undoubtedly threaten Atelier Shantier’s previously wellrespected status as ship builders. By January 1932, the Gor Filipar was completed and ready to set out on her maiden voyage to Yokohama, Japan. Before this could even start though, one more addition to the Philipp’s already troubled start would crop up.

Intelligence had been received by the French police that an attempt to destroy the ship would be made on the 26th of February 1932 as she passed through the Suez Canal. However, the day of the suspected plan passed without incident, and the Gor Filipar proceeded to make a successful first leg of her voyage from Marles to Yokohama.

She arrived there on the 14th of April, and the ship wouldn’t stay long thanks to civil unrest in the region at the time, making stops at Shanghai, Saigon, and Salon before beginning the return west with 518 passengers and 347 crew. Among the passengers aboard for that homewood journey was French journalist Alber Landre, one of the pioneers of investigative journalism, known for exposing and fighting against injustices.

He boarded the ship in China to return to France equipped with notes on a newly discovered scandal. But as the ship made her way west once more, a fire alarm sounded in a storage room containing a stash of gold bullion. This happened on two separate occasions, but each time when the area was inspected, nothing untoward was found.

The fire alarm seemed to be alerting, as noted in the records, for no accountable reason. The Gor Filipar was entering the Gulf of Aiden. Only around 15 minutes after Madame Valentine had first heard that strange crackling noise as she returned to her cabin on the night of the 16th of May at 1:45 a.m., it was reported that a fire had broken out on D-D. This one was real.

The wood paneling along the walls had caught a light from a spark, presumably caused by faulty electrical equipment. A number of crewmen ran immediately to D-D attempted to control the fire. By the time the ship’s captain, Vic, was alerted to the situation, the fire had already spread, engulfing several of the first class cabins and public rooms.

An order to abandon ship was put out, but it was reported after the fact that the late rebels of the passengers and the noise and the ga prevailing on board prevented most of them from hearing the fire alarm. The ship instead had to resort to blaring its sirens. Others were alerted by the horrifying sight of smoke creeping under their cabin doors.

Captain Vic ordered full speed to Aiden, where help would be close by, and the crew focused their efforts on rescuing passengers and fighting the spreading flames. Thick smoke now filled the ship’s corridors. Those on board struggled to see or breathe as they attempted to make their way through the stifling heat to the upper decks.

The engineers were ordered to cut the power in an attempt to prevent further spreading of the fire through the electrical systems conduits, but it was too late. The lights went out, and terrifyingly, some passengers found the passageways blocked and had no choice but to try and escape through their port holes, and others became trapped in their cabins.

Those who made it out onto the deck were met with a distressing sight of lifeboats already a flame, with others requiring hosing down to prevent them from becoming unusable. It was imperative that the remaining lifeboats were launched as quickly as possible. An SOS was sent out around 2:15 a.m. just before the wireless room was completely engulfed.

Thankfully, three different ships responded right away to the distress call. A Russian tanker, the Soviet Sky Neft, and two British freighters, the Massud, and the Contractor. Survivors were brought across to the first ship to arrive, the Soviet Sky. In their lifeboats, the burning wreckage of the Gor Filipar loomed behind them.

Over 400 passengers and crew members were brought aboard the Russian ship, which remained on station until noon the next day to make absolutely sure that everyone possible had been saved. Captain Vic sustained extensive burns as he attempted to check for any last reachable survivors and was the last to leave the wreck around 8:00 a.m.

All the survivors were then transferred from the Soviet sky to the French passenger vessel Andre Lemon, which had arrived and taken to Djibouti. The flaming wreck of the now abandoned Gors Filipar continued to burn as she drifted for a further 3 days before finally sinking on the 19th of May off the coast of Cape Garde. Last seen trying to escape to the water through his room’s port hole, the journalist Alber was among the 52 people who were missing and presumed dead, most having been trapped thanks to how rapidly the flames had spread out of control. The press seized on the idea that Lundre’s demise could not have been

coincidence. and several unfounded conspiracy theories cropped up. One tried to link the assassination of French President Paul Dumeare that had taken place a few days prior to the Gor Philip disaster, though there was no evidence to support any connection between the two.

Another theory implied that the report Laundra had been working on believed to be exposing opium and arms trafficking along with the potential Bolevik interference in SinoJapanese affairs warranted being covered up. This theory took hold given that the only people who Laundra was said to have been confiding the contents of his notes to fellow passengers Alfred Langula and his wife Suzanne perished in a plane crash just a few days after having survived the sinking of the Gor Filipar.

However, the findings of the investigation into the disaster were more practical, concluding that the fire was owed to the lethal combination of a faulty electrical system throughout the ship and its highly flammable decorative elements, which enabled the fire to spread with fearsome speed.

Captain Vic and his crew were criticized for not having responded to the situation quickly enough or for running boat drills and fire drills, but they were ultimately cleared of wrongdoing. New guidelines were put in place recommending the banning of the use of those kinds of flammable materials as well as upgrading onboard firefighting equipment.

The inquiry also proposed that the use of direct current caused too much energy loss at high voltages resulting in excessive heat and that alternating current should be used instead. Faulty electrical would also explain why the Gor Filipar was just one of several French ships of the time to be plagued by fire. A lesson had been taught, not necessarily learned, because it would happen again.

And it was one that sadly came with the loss of over 50 innocent lives. Thankfully, not all maiden voyage disasters have ended in tragedy. Though, as Reuben Griffiths, a lift boy on the RMS Magdalina, found himself and his crew mates rowing towards the beautiful white sands of Copa Cabana Beach, their experience of the last few hours was far from relaxing, and they were making this trip in a lifeboat.

After the Second World War, many shipping companies found themselves in need of new vessels to replace all those that had been lost. One of these was the British Royal Mail Line, who had lost the 14,000 ton liner Highland Patriot during the war. The Magdalina would be her replacement.

Ordered in 1946 and built at Belfast by Highland and Wolf, that legendary shipyard, the Magdalina was 17,547 gross registered tons, about 570 ft or 173 m long. She was a combination cargo passenger liner and the first passenger ship built by Harland and Wolf since the war. Completed on the 18th of February 1949, the Magdalina had a distinctive island bridge design separating off the bridge from the passenger accommodations and the rest of the ship’s superructure.

A style reminiscent of Harland and Wolf’s big four built years and years ago for the White Star Line. The Magdalina had a part riveted, part welded construction and featured all the usual watertight subdivisioning as well as a double bottom to help prevent grounding damage.

On the 9th of March 1949, she embarked from the King George V dock in London on her maiden voyage bound for Buenes Aerys, Argentina. Captained by Douglas RV Lee, the Magdalina would be his final assignment before retirement. After a successful 40-year long career, the first leg of her journey was without issue.

She reached her destination according to schedule and in preparation for her return, she was loaded with a substantial cargo of Argentine beef and then proceeded to pick up a cargo of Brazilian oranges at Santos. Along with her refrigerated cargo, the Magdalina also had 347 passengers on board and 237 crew.

She departed Santos on the 24th of April, heading northeast towards her next port of call on the way home, Rio de Janeiro. As they steamed on though, it became apparent they were tracking more north than intended. Captain Lee ordered that they alter course to correct this. First at 6 p.m. and then again at 7. They reduced their speed from around 18 knots down to 13 1/2.

All seemed okay. The captain ate dinner in the saloon before returning to the bridge and then turning in for the night at 10:45 p.m. But by 2:30 the next morning, first officer Sirill Senior, serving as officer of the watch, alerted the captain that the Magdalina was now some 2 and 1/2 m north of her course.

Her heading was adjusted once more, and the captain returned to his cabin. But just 2 hours later, around 2:30 a.m., the Magdalina was once again off course. Suddenly ahead of them loomed what appeared to be a ship without lights. It was too late to prevent an impact though as it turned out it was not another vessel they’re about to collide with.

In the early hours of the morning on the 25th of April, the Magdalina had struck the Tucas Islands reef and was now stuck. Passengers and crew alike were jolted awake by the sudden impact. The ship’s refrigeration engineer, Bill Harkness, described how the big crunch was so severe it threw me across against my bunk. The collision tore into the number three hold and water began flooding in.

An SOS was quickly sent out and it was received by the Brazilian Navy. The Magdalina’s passengers were ordered to the lifeboats where they anxiously awaited the arrival of the rescue ships. With nearly 5,000 tons of cargo on board, the decision was made to attempt to unload some of it to lighten the ship in an attempt to refloat her the following day.

Some of the 20,000 cases of oranges were transferred to barges. Others were simply jettisoned overboard, and a further 2,000 tons of oil were discharged, all with some difficulty thanks to the increasing swell. Crowds gathered on the beaches on the morning of the 26th of April to watch as the Magdalina was towed towards Rio de Janeiro.

But they surely weren’t expecting quite so dramatic a show as they ended up getting. The ship found herself caught in a heavy swell approaching a bay. As the onlookers watched in disbelief, the rivets shot out. Topside plating started buckling and finally the shell plating ripped up. The Magdalina was tearing apart. The anchors were dropped and for a second time the abandoned ship order was given, allowing the remaining few passengers and then the crew to get safely to shore. Of course, Captain Lee was the last to leave. And not a moment too

soon. With a noise described as being like the felling of a giant tree, the Magdalina had broken in half close to the impressive backdrop of Sugarloaf Mountain. splitting off of that forward bridge section. It was as if she’d been sliced clean through with a knife.

The bow and the midship section sank quickly at the harbor entrance with only part of her mass still showing above the water while the stern drifted further towards land, eventually beating itself. But how exactly could this have even happened? The brand new ship well equipped with the latest navigational equipment. Yet her career ended before it had even truly begun.

A court of inquiry in London in September 1949 placed the blame on Captain Lee and his first officer for their navigational errors and for failing to take sufficient and timely action. Their certificates were both suspended for 2 years and one year respectively. Up until the 70s, a boy with a bell marked the location of the ship’s sunken forpart.

Most of the bow section of the wreck has since been demolished because it remained a hazard to any large ships looking to enter the bay in the decades after the sinking. In a far happier turn of events than many maiden voyage disasters though, not a single life was lost in the sinking of the Magdalina. Even some of her jettisoned cargo actually survived the ordeal.

The shores of Copa Cabana Beach were littered with washed up oranges and even intact bottles of beer that were found among the ship’s scrap. Not so fortunate were the Magdalena’s owners who faced the embarrassing and expensive loss of a brand new ship.

A blow no doubt softened by the fact that the Royal Mail Lines was awarded an insurance check of around2,295,000. That’s around £70 million in today’s money. This massive sum made headlines at the time as the largest insurance payout for any marine casualty in British history. Not all ships are destined for long careers, and those with tragic legacies are often the ones we tend to remember the most. Many of today’s safety standards are built on the sometimes painful lessons of the past.

And we would do well to not forget that rapid innovation can sometimes have dire consequences. A ship’s maiden voyage is an exciting time to be sure. It’s an achievement by both the people that designed and built her. Yet, there’s always a lingering notion of worry and anxiety for the owners and the operators.

Fortunately, no big passenger ship has been lost on its maiden voyage since the Hans head to. But it doesn’t mean that ship builders and operators should ever become complacent.

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load