A leatherbound book sits on a wooden table. Forbidden, dangerous, impossible. September 1944. Camp Clinton, Mississippi. A German colonel reaches for philosophy his regime burned. This is the story of how a prisoner of war became a professor of freedom. May 7th, 1944.

Colonel Friedrich Hartman stood in the ruins of what had been his command post near Anzio. His hands moved automatically, destroying documents, burning orders, erasing evidence of decisions he’d made without question for 12 years. American artillery fire crept closer. The ground shook, his agitant appeared at the doorway, face pale. Hair Oburst, they’ve broken through the western perimeter.

Hartman looked at the flames consuming papers stamped with eagles and swastikas. 12 years of service. 12 years of following every directive from Berlin. 12 years of certainty about Germany’s righteous cause. He picked up his service pistol, checked the magazine, and walked outside into chaos. The Americans arrived 3 hours later. Hartman watched them approach from his position beside the road. They moved differently than he expected.

No rage, no vengeance, just tired men doing a job. A young lieutenant approached, weapon raised but not threatening. Colonel, you are now a prisoner of the United States Army. The words landed without drama. Hartman removed his sidearm, handed it over, and felt something shift inside him.

Not relief, not shame, just emptiness where certainty had been. They loaded him onto a truck with 47 other German officers. The vehicle bounced along roads cratered by shells. Hartman’s stomach dropped. This was surrender. This was defeat. This was everything the furer had promised would never happen. An American sergeant tossed them ration boxes. Hartman caught his, opened it.

Cigarettes, chocolate, cheese, crackers, coffee. He stared at the contents. His own men had been subsisting on black bread and airs coffee for months. The Americans were feeding prisoners better than Germany fed its fighting troops. Major Wilhelm Kesler, sitting beside him, whispered, “Propaganda! They want us compliant.” Hartman nodded, but his hands trembled as he unwrapped the chocolate.

When was the last time he’d tasted real chocolate? 1941? 1942? He bit into it. The sweetness exploded across his tongue. His eyes widened. This was real. This abundance was real. The truck rolled past American supply depots. Mountains of crates, rows of vehicles, fuel drums stacked 20 ft high. Hartman counted, force of habit from general staff training.

50,000 gallons, maybe more, just sitting there, unguarded, unused, excessive. He’d been told America was weak, decadent, collapsing under its own contradictions. He saw power. He saw wealth. He saw a machine that could bury the Reich under sheer weight of resources. And if this fundamental truth was propaganda, what else had been lies? June 3rd, 1944.

Hartman stepped off the train in Mississippi. Heat hit him like a physical force. The air was thick, wet, suffocating. Guards directed them toward rows of barracks surrounded by wire fences. Not the brutal camps he’d expected. Clean buildings, organized rows, medical facilities visible in the distance. An American captain processed them. Name, rank, service number.

Date of capture. The captain spoke German fluently without accent. Colonel Hartman. You’ll be housed in officer barracks 7. Meals at 0600, 1200, and 1800 hours. Library access after orientation. Hartman’s breath caught. Library. Yes, Colonel. books. We believe in the Geneva Convention books. The word echoed strangely.

In 12 years of national socialist rule, Hartman had read what was permitted. Military texts approved philosophy, sanitized history. The thought of a library, unrestricted, uncensored, felt dangerous and impossible at once. Barrack 7 housed 32 German fieldgrade officers, majors, lieutenant colonels, three full colonels, including Hartman.

They unpacked in silence, each man processing his new reality. The bunks had mattresses, real mattresses. The windows had screens but no bars. The doors locked from inside. That first night, Hartman lay awake listening to American guards walk their rounds. Their boots struck pavement in steady rhythm.

No shouting, no brutality, just professionals doing their duty. He thought about the camps in the east, the places he’d heard whispers about but never questioned, the measures taken against partisans, against enemies of the Reich, against those deemed subhuman. His jaw clenched. Those were necessary. Those were justified. Those were He couldn’t finish the thought.

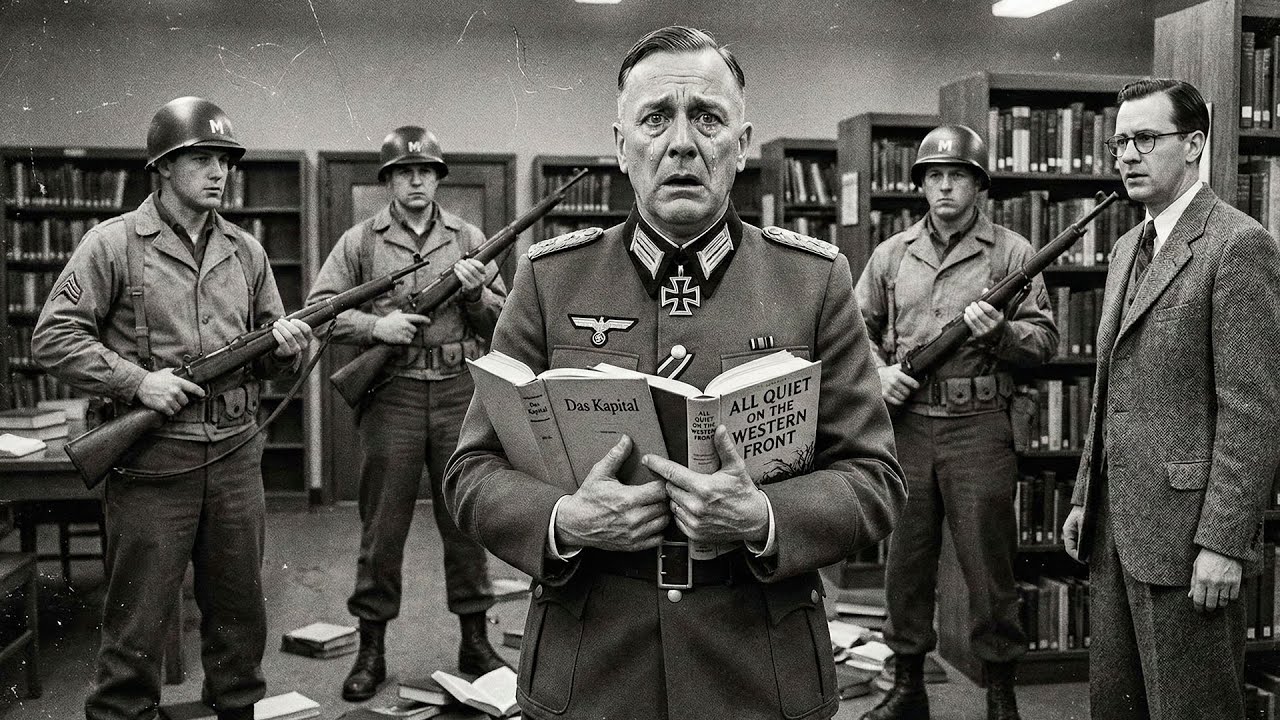

If this moment of doubt resonates with you, if you recognize how easily certainty can crack, a like shows that more forgotten transformation stories matter. Now the real journey begins. June 9th, 1944, 6 days after arrival, Hartman entered the camp library for the first time. He stopped three steps inside the door. His voice cracked. Got him. 12,000 volumes lined the shelves.

American books, British books, French books, books in German from before the Reich, books banned in 1933, books burned in 1933, books that could have gotten him arrested for possessing in 1933. An American librarian, Sergeant Morrison, according to his name plate, approached, “Conel, you’re free to read anything here. We ask only that you respect the materials and return them promptly.” Hartman’s hand stopped moving.

He stood paralyzed before shelves containing Thomas Man, Eric Maria Remark, Stefan, writers whose names had been erased from German culture. His stomach dropped as realization hit. For 12 years, someone had decided what he could read, what he could think, what questions he could ask. He reached for a book. His fingers touched the spine of John Stewart Mills On Liberty. The English title meant nothing to him yet. He opened it.

The pages smelled of paper and possibility. He found a German translation three books down. He pulled it from the shelf. He sat at a reading table. He began to read. The only freedom which deserves the name is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs.

The words hit like artillery. Hartman read the sentence again, then again. His breath caught in his throat. Pursuing our own good in our own way. The concept felt alien after 12 years of collective purpose, collective will, collective submission to the furer’s vision. He read for 4 hours that first day.

He returned the next day for 6 hours, then ate, then every waking moment not occupied by roll call or meals. Major Kesler confronted him after 2 weeks. Friedrich, you’re spending too much time with enemy books. This is psychological warfare. They’re trying to break us. Hartman looked up from Alexis Dtoqueville’s democracy in America.

His eyes widened with something between fear and exhilaration. Wilhelm, did you know that in America citizens can criticize their government without disappearing? That newspapers can publish opposing viewpoints without being shut down? That enemy propaganda? I thought that too. Hartman’s voice dropped to a whisper.

But I’ve been reading their philosophers, their historians, their own critics of democracy. Wilhelm, they allow criticism of their own system. They publish it. They teach it in universities. What kind of tyranny encourages dissent? Kesler walked away. He never spoke to Hartman again. August 1944, 3 months in captivity.

Hartman sat in the library reading Hannah Artrent’s analysis of totalitarianism. His hands trembled as he turned pages. Each paragraph dismantled another piece of his world view. Each chapter exposed mechanisms he’d witnessed but never questioned. The use of propaganda to create alternative reality. Check. The elevation of the leader to infallible status. Check.

The identification of scapegoat populations. Check. The suppression of independent thought through fear and social pressure. Check. his jaw clenched as he read descriptions of how totalitarian regimes function. This wasn’t enemy propaganda. This was systematic analysis backed by historical evidence. This was scholarship.

This was thinking he’d been trained to dismiss as Jewish intellectualism, but could no longer ignore. An American educational officer, Captain Lawrence Mitchell, ran weekly discussion groups. Voluntary attendance, no pressure, no coercion. 15 German officers showed up the first week, 40 by the fourth week. Hartman attended them all. Mitchell posed questions, then listened. He didn’t lecture. He didn’t propagandize.

He asked, “What is the purpose of government? What right should individuals have? How do we balance collective good with personal freedom? What happens when we surrender critical thinking to authority?” The discussions ran three hours, sometimes four. German officers argued, debated, challenged each other. Some defended the Reich with passionate conviction. Others wavered.

A few, like Hartman, found their certainties collapsing under the weight of evidence and logic. October 12, 1944. Mitchell assigned readings from multiple perspectives. Edmund Burke’s conservatism, John Lock’s liberalism, Karl Marx’s criticism of capitalism, Adam Smith’s defense of markets. Not propaganda. Not indoctrination, just thinking.

Critical analysis of competing ideas. Hartman’s stomach dropped when he realized what had been stolen from him. Not just 12 years. His entire education. His university training had taught him to follow doctrine, not question it. His general staff education had taught him to execute policy, not examine its foundations. He’d been trained as a tool, not a thinker.

He walked back to his barracks that night and vomited behind the building, not from illness, from rage at his own blindness. December 15th, 1944, 7 months in captivity, Mitchell brought in news reels from liberated France. The camp theater filled with 200 German officers. The projector started. Images flickered across the screen. Footage from concentration camps. The theater went silent. Completely silent.

300 men stopped breathing simultaneously. Bodies stacked like cordwood, skeletal, burned, dumped in pits, survivors behind wire, eyes hollow, skin stretched over bones, branded with numbers, gas chambers, crematoria, systematic, industrial, efficient. Hartman’s breath caught. His hands stopped moving. His vision narrowed. He expected death in war.

He expected casualties. He expected even brutality in combat. He never expected this. This machinery of death, this bureaucratic extermination, this systematic elimination of entire populations. An SS officer three rows back shouted lies. Allied fabrication. But Hartman recognized the camps, the architecture, the German efficiency, the meticulous recordkeeping visible in captured documents on screen. This was real. This was German.

This was what the whispers had been about. This was what he’d chosen not to investigate. This was what he’d dismissed as exaggeration. This was what he’d enabled by following orders without question. The news reel ended. The lights came up. Men sat frozen. Some wept openly. Others stared blankly ahead. Many walked out in furious denial.

Hartman sat paralyzed in his seat for 20 minutes after the theater emptied. That night he wrote in the journal the Americans had provided, “I have been complicit in the greatest crime in human history. Not through action, but through willful blindness. I saw evidence. I heard whispers.

I asked no questions because asking questions was dangerous, uncomfortable, disloyal. I chose the comfort of certainty over the difficulty of truth. I am guilty. Not of murder, but of something perhaps worse. Intelligent cowardice masquerading as duty. He wrote for four hours. Five pages became 10. 10 became 20. He documented every moment he’d suppressed doubt. Every order he’d executed without asking where it led.

Every time he’d chosen comfort over conscience. When he finished, his hands were shaking. His face was wet. He felt empty and horrified and strangely free. The old certainties were dead. Now came the harder work, building something true. January 1945, 8 months in captivity, Hartman requested formal enrollment in the American Re-education Program.

Captain Mitchell interviewed him personally. Colonel, why this change? Hartman met his eyes. Because I was educated to obey, not to think. I want to learn how to think. Mitchell assigned him readings on democratic theory, constitutional government, separation of powers, protection of minority rights, free speech, free press. Hartman consumed them hungrily.

He read Montiscu on separation of powers and saw how concentration of authority enabled tyranny. He read Jefferson on natural rights and saw how states could be constrained by principles higher than state power.

He read Madison on factionalism and saw how democracies managed conflict through process rather than suppression. He also read democracy’s critics. He read Plato’s warnings about mob rule. He read conservative concerns about chaos and instability. He read socialist critiques of inequality and exploitation. Mitchell insisted, “Democracy isn’t perfect, Colonel. It’s just better than the alternatives.

It’s a system that can correct itself without violence, that can change without revolution, that can accommodate disscent without collapse. Hartman spent his mornings reading, his afternoons in discussion groups, his evenings writing analyses of what he’d learned.

He dissected propaganda techniques used by the Nazi regime, the big lie repeated until believed, the scapegoating of minorities, the cult of personality, the suppression of alternatives, the creation of perpetual crisis requiring absolute authority. He also studied American propaganda. He found it crude, obvious, often ineffective, not because Americans were inept, but because democratic societies couldn’t achieve the total control necessary for complete manipulation. Free press meant competing messages.

Free speech meant constant criticism. Pluralism meant fractured narratives impossible to unify. This was democracy’s weakness and its strength. It couldn’t lie efficiently enough to maintain totalitarian control. February 23, 1945. News reached the camp that Dresden had been bombed. Massive civilian casualties, firestorm destruction.

German officers raged about Allied war crimes. Hartman listened, then spoke quietly. Yes, it was terrible. Yes, civilians died. But ask yourselves, who started bombing civilian populations? Who destroyed Rotterdam, Warsaw, Coventry, London? Who built a regime on violence and then condemned others for responding with violence? We wanted total war. We got it.

An argument erupted, shouting, “Accusations of betrayal.” Hartman didn’t back down. Not anymore. He’d learned that truth wasn’t betrayal. Complicity was. May 8th, 1945. The war ended. German surrender. Total defeat. The Reich that was supposed to last a thousand years lasted 12.

Hartmann sat in the library reading the news. His hands were steady, his face calm. He felt no joy at Germany’s defeat, but no mourning either, just grim acknowledgement that catastrophe had ended. Camp regulations changed. German officers could now apply for early repatriation or extended education programs in the United States. Most chose repatriation. They wanted to return home, find families, rebuild lives. Hartman chose education.

Captain Mitchell helped him apply to American universities. Colonel, your English is excellent, your academic potential clear, but you understand you’ll be starting over. You’re 42 years old. You’ll be in classes with 20 year olds. I wasted 12 years serving a lie. I’ll spend however many I have left serving truth.

September 1945, Hartman enrolled at the University of Chicago, Department of History. He shared classes with American veterans, young students, refugees from Europe. He was the oldest person in most rooms. He was also the most motivated. His first papers were clumsy. He’d been trained to assert, not argue, to proclaim, not prove, to follow authority, not build cases from evidence. Professors returned his work covered in red ink. You’re making claims without evidence.

You’re asserting without demonstrating. You’re preaching, not analyzing. It was humiliating. It was necessary. It was freeing. He learned to question his own assumptions, to seek evidence that contradicted his hypothesis, to revise conclusions when data demanded it. He learned the discipline of scholarship, rigorous, humble, self-correcting.

June 1947, he completed his master’s thesis, Mechanisms of Consent: How Democratic Germans accepted totalitarian rule. It analyzed the step-by-step process by which a free society surrendered freedom, the economic crisis creating desperation, the scapegoating providing simple answers, the propaganda creating alternative reality, the social pressure enforcing conformity, the legal mechanisms normalizing oppression.

the point of no return. When resistance became impossible, his adviser called it groundbreaking. Publishers called it controversial. German expatriots called it selfserving. Hartman didn’t care about reception. He cared about truth. Subscribe to hear more stories of transformation that history tried to bury.

Stories that show how even the most indoctrinated minds can choose truth over comfort. Now his real work begins. September 1951, Hartman defended his doctoral dissertation at Colombia University, The Architecture of Propaganda in Totalitarian Regimes: A Comparative Analysis. It examined how Nazi Germany, Soviet Russia, and Fascist Italy created systems of belief that supplanted objective reality.

How they used education, media, ritual, and social pressure to manufacture consent. how they destroyed critical thinking through fear, isolation, and constant messaging. The dissertation committee grilled him for four hours. They challenged his methodology, questioned his sources, probed his conclusions.

Hartman answered calmly, citing evidence, acknowledging limitations, defending his analysis. When they finished, the chair spoke, “Dr. Hartman, congratulations. This work will become foundational to the study of political manipulation and mass psychology.” He was 50 years old.

He’d earned the title he’d previously held through military rank, but now through scholarship. Doctor, not oburst, not colonel. Doctor, a title earned through thought, not obedience. Universities competed to hire him. He chose a small college in Massachusetts. Not prestigious, not famous, but serious about teaching, about shaping young minds to resist what he hadn’t resisted. His first lecture to freshmen began with a story. I was a colonel in the German general staff.

I was educated at the finest militarymies. I spoke four languages. I had a doctorate in military history. I was intelligent, cultured, well- read within permitted boundaries. And I served evil for 12 years because I never learned the most important skill a citizen can possess, the ability to question authority when authority demands immorality. This class will teach you that skill. Students filled every seat. Word spread.

Within three years, his courses required waiting lists. His lectures drew audiences beyond enrolled students. He taught propaganda analysis, critical thinking, democratic theory, totalitarian systems, and the psychology of obedience. He used case studies from Nazi Germany, but also from American history. Slavery rationalized through pseudocience.

internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, McCarthy era persecution of alleged communists. He taught students that propaganda wasn’t uniquely German, that manipulation wasn’t uniquely fascist, that every society needed citizens capable of recognizing when authority demanded surrender of conscience.

1955, Hartman published the obedient mind, how intelligent people serve evil. It became required reading in universities across America and Europe. It analyzed how education systems could create compliance rather than critical thinking. How social pressure enforced conformity. How careerism rewarded obedience. How specialization created moral blindness. Experts following orders in narrow domains without seeing larger implications.

The book received praise from scholars and attacks from nationalists. German reviewers split between those who saw it as necessary reckoning and those who saw it as betrayal. Hartman expected this. Truth always offended those invested in comfortable lies. June 1957, Hartman received an invitation from the newly formed Federal Republic of Germany.

The government wanted to establish educational standards preventing resurgence of extremism. They wanted Hartman’s expertise. He hesitated. Returning to Germany meant confronting his past directly, facing people who remembered him as a colonel, not a professor, answering for choices made under a regime he now dedicated his life to exposing. He accepted Bon, West Germany. The new capital, Hartman presented his recommendations to the Ministry of Education.

Create curricula teaching students to question, not obey. Include primary sources showing how propaganda works. Teach multiple perspectives on history, including Germany’s crimes. Train teachers to encourage debate, not demand consensus. Protect academic freedom fiercely. Never again allow government to dictate historical truth. Conservative officials resisted. Dr.

Hartman, we need national pride, not national shame. We need to move forward, not dwell on the past. Hartman’s voice was steady but firm. You cannot move forward by forgetting. You cannot build democracy on lies about history. Pride built on denial becomes nationalism. Nationalism becomes extremism. Extremism becomes catastrophe. I know. I lived it.

After 3 months of negotiations, compromises, and political maneuvering, the ministry adopted 70% of his recommendations. Not perfect, but progress. Real progress toward a Germany that could face its past and build a better future. 1958 Hartman accepted a permanent position at H Highleberg University chair of political science.

He returned to Germany not as a soldier but as an educator not as a servant of the state but as a guardian of critical thought. His lectures at H Highleberg attracted students from across Europe. He taught them how to identify manipulation, how to recognize when leaders were lying, how to resist social pressure toward conformity, how to maintain intellectual independence even when surrounded by certainty, how to say no when authority demanded immorality.

He also trained teachers, hundreds of them, future professors, secondary school instructors, primary educators. He taught them pedagogy of liberation, education that freed minds rather than controlled them. Education that encouraged questions rather than memorized answers. Education that produced citizens rather than subjects.

October 1963, Hartman delivered the keynote address at the German educational conference in Munich. 1500 educators attended. He was 70 years old. His hair was white. His face was lined. His voice was strong. I was educated to be the perfect servant of totalitarianism. I was taught to master facts without questioning their meaning.

To follow orders without examining their morality, to serve authority without recognizing when authority became tyranny. My education was rigorous, demanding, comprehensive, and completely successful at producing exactly what the regime wanted. An intelligent, capable, obedient functionary who never asked the most important questions.

The question is not whether students learn mathematics, history, languages, sciences. The question is whether they learn to ask why, who benefits, what is hidden, what alternatives exist, what would happen if I refuse. We must educate for disobedience, not anarchctic rejection of all authority, but principled resistance to immoral authority. We must teach students that some orders must not be followed, that some laws must be challenged, that some consensus must be rejected, that conscience matters more than career. I failed this test for 12 years.

Millions died because people like me chose comfort over conscience. We cannot undo that catastrophe. But we can ensure it never happens again by creating citizens who cannot be manipulated, cannot be intimidated, cannot be made complicit in evil through intellectual cowardice. The audience rose. Applause lasted 5 minutes.

not for Hartman personally, but for the principle he represented, that transformation was possible, that guilt could become responsibility, that past failure could produce future wisdom. By 1965, programs based on Hartman’s curriculum were implemented in 78% of West German schools. Students learn to analyze propaganda, to recognize rhetorical manipulation, to question authority while respecting legitimate governance, to distinguish between patriotism and nationalism, to see how ordinary people become complicit in extraordinary evil. Hartman trained 200 doctoral students during his tenure at H Highleberg. They became professors,

authors, policy makers, journalists. They spread his methods throughout German education and beyond. His intellectual descendants taught in France, Britain, America, Israel. His ideas influenced curricula across democratic nations. April 1972. Hartman was 79 years old. He announced his retirement. His final lecture at H Highleberg drew 3,000 people.

They filled the auditorium, overflowed into hallways, watched on closed circuit television in adjacent buildings. He walked slowly to the podium. He refused assistance. He looked at the audience, students, colleagues, former students now themselves professors, journalists, politicians. When I was captured in 1944, I believed I knew truth.

The Reich was righteous. Germany was superior. Our enemies were inferior. Our cause was just. Our victory was destiny. I believed these things not because I was stupid, but because I was educated to believe them. Not because I was evil, but because I was trained not to question. The greatest gift the Americans gave me was not food, not shelter, not safety. It was doubt.

They gave me access to ideas that contradicted my certainties. They created space for questions I’d been afraid to ask. They showed me that real strength lies not in absolute conviction, but in the courage to examine your convictions. Some of you know my story.

former Nazi colonel becomes American professor becomes advocate for democracy. It sounds redemptive, heroic even. It was not. It was painful. It was humiliating. It meant acknowledging I’d wasted 12 years serving evil while believing I served good. It meant accepting that my intelligence, my education, my sophistication meant nothing without moral courage.

I tell you this not to inspire you, but to warn you. You are educated. You are intelligent. You are sophisticated. And you are just as vulnerable to manipulation as I was. More vulnerable perhaps because you believe education makes you immune. It does not. The only immunity is eternal vigilance. Constant questioning. Perpetual skepticism toward power, including power that claims to serve good purposes, especially power that claims to serve good purposes. I was captured by Americans who treated me with dignity. I was given books that

challenged my beliefs. I was taught to think by people who had every right to hate me. This was not deserved. This was grace. I spent the rest of my life trying to earn it by ensuring future generations would not need the catastrophe of defeat to learn what I should have known all along. Think, question, resist, refuse complicity, choose conscience over comfort.

These are not abstract principles. These are concrete actions required of every citizen in every moment when authority demands surrender of judgment. You will face those moments not dramatically, not obviously. They will come as small compromises, minor obediences, subtle surreners of principle for practical benefit. You will rationalize them as necessity, as pragmatism, as teamwork.

Do not. The catastrophes of history are built from small surreners accumulated over time until resistance becomes impossible. You must resist early, resist constantly, resist loudly before the small surreners become complicity in great evil. This is my final lecture, my final plea, my final warning. I failed. Do not repeat my failure.

The cost is too high. He finished. Silence filled the auditorium. 3,000 people sat motionless. Then one student stood, then another, then all 3,000. They did not applaud. They stood in silent acknowledgement of what he’d said, what he’d lived, what he’d become. Friedrich Hartman died August 7th, 1976. He was 83 years old.

Obituaries appeared in newspapers across Europe and America. They called him educator, scholar, advocate for democracy, voice of conscience. His students established the Hartman Foundation for Critical Education. It funded programs teaching propaganda analysis and critical thinking in schools worldwide.

It awarded scholarships to students studying political manipulation, mass psychology, and democratic theory. It sponsored research on how societies resist extremism. His papers were archived at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and at H Highleberg University. Scholars studied his transformation, his methods, his impact. Psychologists analyzed how he overcame indoctrination.

Educators examined how he translated personal transformation into pedagogical practice. Historians documented his influence on post-war German education. By 2015, programs based on his curriculum were taught in schools across 43 countries. More than 10 million students had learned propaganda analysis, critical thinking, and democratic citizenship using methods he pioneered.

His books remained required reading in universities studying totalitarianism, propaganda, and political psychology. His greatest legacy was not his scholarship, though that was significant. His greatest legacy was not his teaching, though that was transformative.

His greatest legacy was demonstrating that transformation was possible, that complicity could become resistance, that obedience could become critical thought, that even after 12 years of serving evil, a person could choose truth and spend the rest of his life earning redemption through service to others. He never claimed to be forgiven. He never sought absolution. He simply worked.

every lecture, every book, every student, every curriculum reform. Work that said, “I was blind, but now I see. I was complicit, but now I resist. I failed, but you do not have to fail. Learn from my catastrophic error. Think, question, refuse complicity. Choose conscience.” This was not redemption. This was responsibility accepted and honored through decades of difficult, unglamorous work.

This was one man’s answer to the question, “What do you do after you’ve served evil? You spend the rest of your life ensuring others will not.

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load