The mechanics at Townsville looked at Major Paul Gun like he had lost his mind. In his hands, he held a crumpled sketch showing something that defied every principle of aircraft design. A medium bomber transformed into a flying battleship bristling with eight forward-firing 50 caliber machine guns where the glass nose used to be.

You want us to do what? Sergeant Frank Morrison asked, wiping grease from his hands with a rag that was dirtier than his fingers. Strip out the bombardier’s compartment, Gun said. His voice carried the flat certainty of a man who had stopped caring about other people’s opinions long ago. Replace it with solid metal.

Mount four guns in the nose, two on each side of the fuselage. Then we’re going to teach these birds to skip bombs like stones on a pond. It was August 1942, and the war in the Pacific was not going well. The Japanese controlled vast swaths of territory from Burma to New Guinea, and their supply convoys moved with impunity across the Bismar Sea.

American bombers had tried to stop them, dropping their payloads from 20,000 ft, but hitting a moving ship from that altitude was almost impossible. The bombs would fall, the ships would turn, and thousands of tons of supplies and reinforcements would reach their destinations untouched. Something had to change.

And Paul Irvin Gun, 43 years old, former Navy pilot, former airline owner, now a captain in the Army Air Forces, believed he knew what that something was. “Sir, with respect,” Morrison said carefully. “Nobody’s ever done anything like this. The weight distribution alone would throw off the aircraft’s balance. You’re talking about putting 2,000 lb of ammunition in the nose. The thing won’t fly straight.

Then we’ll learn to fly it crooked.” The mechanics exchanged glances. They had heard stories about this man, how he had flown unarmed transport planes into the Philippines after Pearl Harbor, dodging Japanese fighters to deliver medicine to troops on Baton, how he had appropriated Dutch B25s sitting unused in Australia, claiming them for the American war effort before the paperwork caught up.

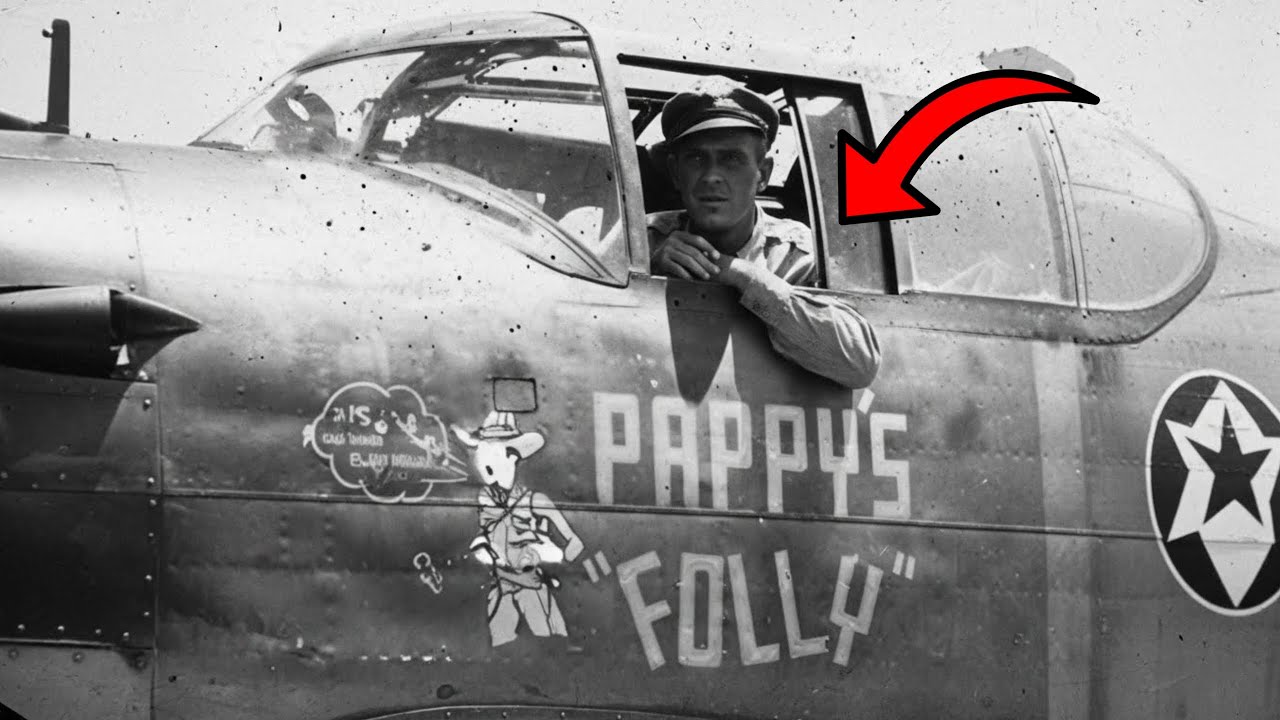

How his wife and four children were prisoners of the Japanese in Manila, interned in camps where disease and hunger killed more than bullets. Peppy Gun, they called him. The old man who refused to die. I need a prototype in two weeks. Gun continued. We’ve got wrecked P40s sitting in fields across Queensland with perfectly good machine guns in their wings.

Strip them out, mount them forward, and find me a bombardier seat we can remove. I want every ounce of glass gone from that nose. Morrison looked at the sketch again. It was rough, drawn on the back of a requisition form, but the concept was clear enough. A B-25 Mitchell, one of the most versatile bombers in the American arsenal, converted into something entirely new.

A gunship that could sweep in at mast head height, guns blazing, and drop bombs that would skip across the water like flat rocks on a lake. Even if we build it, Morrison said, “Even if it flies, you’re talking about attacking ships from 50 ft off the water. The anti-aircraft guns will tear you apart.

” Gun smiled, but there was no humor in it. That’s why we need the gun, Sergeant. When 850 calibers are pouring lead into your deck, you don’t have time to aim at the plane that’s doing the shooting. He left the maintenance hanger without waiting for a response. Behind him, the mechanics gathered around the sketch, pointing and arguing.

Some thought it was genius. Others thought it was suicide dressed up as innovation. All of them knew they would build it anyway because orders were orders. And this particular order came from a man who had earned his rank in ways none of them could imagine. Over the next two weeks, the 81st Air Depot group worked around the clock.

They scavenged guns from crashed fighters, ammunition from supply dumps, and steel plating from wherever they could find it. The first B-25 to undergo the modification was a warweary C model that had already survived two emergency landings and bore the scars to prove it. When they were finished, the aircraft looked nothing like the graceful bomber that had rolled off the assembly line in Englewood, California.

Its nose was blunt and ugly, studded with gun barrels. The glass that had once housed a bombardier was gone, replaced by solid metal. It was heavier, slower, and according to every aeronautical principle, should have been impossible to fly. Gun climbed into the cockpit on September 2nd, 1942 and took it up.

The aircraft handled like a drunk mule, its nose pulling down constantly from the extra weight, but it flew. And when gun lined up on a target wreck offshore and pressed the firing button, eight streams of tracer fire converged in a cone of destruction that shredded everything in its path. He landed 30 minutes later, his arms aching from fighting the controls, and walked up to Morrison with the same humorless smile.

Build me 15 more. The mechanics stared at the aircraft, at the thin trails of smoke still rising from the gun barrels, at the brass casings scattered across the sand where the ejection ports had expelled them. Nobody called it impossible anymore. Lieutenant Colonel Edward Lner had been a bomber pilot for 18 months, and he had never seen anything like the aircraft sitting on the apron at Port Moresby.

It was February 1943, and the modified B-25s had finally arrived in numbers sufficient to form a proper strike force. 12 aircraft, each carrying eight forward-firing guns and a belly full of 500 lb bombs equipped with delayed action fuses. The 90th Bombardment Squadron had been training for weeks, practicing the techniques that Gun and his engineers had developed through trial and error.

Low-level approach at 200 f feet. Speed at 250 mph. Target acquisition from four miles out. Guns blazing at maximum range to suppress anti-aircraft fire. Bombs released at 500 yd, skipping across the water like stones. Pull up hard to clear the masts, then bank away while the tail gunner confirmed the hit. It sounded simple. It was anything but.

The timing has to be perfect, Lner told his crews during the briefing. Too early and the bomb sinks before it reaches the target. Too late and you’re part of the explosion. We’ve lost two aircraft in training already. Both crews dead. This is not a job for the careless. The pilots listened in silence.

Most of them were young, barely out of their 20s, with faces that had aged 10 years in the month since they arrived in the Pacific. They had seen friends die, had written letters to parents and wives explaining that someone they loved was not coming home. They knew what they were being asked to do, but they also knew what was at stake.

Intelligence reports had been coming in for weeks about Japanese convoy preparations at Rabbal. The enemy was planning something big, a major reinforcement of their positions in New Guinea that could change the balance of the entire campaign. If those troops reached delay, the Allied offensive would stall. Thousands of additional soldiers would be fighting Australian and American forces in the jungles.

The convoy had to be stopped and conventional bombing had proven useless. We’ve got maybe one chance at this. Lner continued. When that convoy comes, every aircraft we have will be in the air. B7s at high altitude, our B-25s at deck level. The heavy bombers will keep their fighters busy while we go in low.

If we do this right, we’ll prove that air power can control the sea lanes. If we fail, he paused. We won’t fail. Captain Ralph Delo, one of LNER’s flight leaders, studied the map pinned to the briefing room wall. The Bismar Sea was a vast expanse of water between New Britain and New Guinea, dotted with islands and sholes.

The Japanese would have to transit through the Vidia straight to reach Lei, and that narrow passage offered the perfect killing ground. What about fighter cover? Delo asked. They’ll have zeros. Maybe a hundred of them flying escort. Our P-38s will engage them while we make our runs, but expect opposition. Expect casualties.

This is going to be the biggest air sea battle of the war so far. The room fell silent again. That night, Lner sat alone in his quarters, writing a letter to his wife back in Ohio. He told her about the weather, about the food, about the mosquitoes that made sleep impossible some nights. He did not tell her about the mission, about the odds, about the knot of fear that had settled in his stomach and refused to leave.

He had volunteered for this. They all had. And now the moment was approaching when theory would become reality. When sketches on the back of requisition forms would be tested against Japanese steel and Japanese guns. The waiting was the hardest part. On February 28th, word came that the convoy had left Rabul. eight destroyers, eight troop transports, carrying nearly 7,000 soldiers, and enough supplies to sustain them for months.

The ships were moving at seven knots, hugging the coast of New Britain, trying to stay under cloud cover as long as possible. It didn’t matter. Allied codereakers had intercepted the Japanese communications. They knew the route, the timing, the destination. For once, the Americans had the advantage of surprise. Launch at dawn, Lner told his crews.

Full bomb loads, every gun loaded and ready. This is what we’ve been training for. The night passed slowly. Some men slept, exhausted beyond the reach of fear. Others played cards, wrote letters, prayed. The ground crews worked through the darkness, checking fuel levels, loading ammunition, securing bombs in the belly racks.

By 0500, the first light was touching the eastern horizon, painting the clouds in shades of pink and gold. The B-25 sat on the runway, their engines ticking with residual heat from the pre-dawn warm-ups. Lner climbed into his aircraft, settled into the pilot seat, and ran through his checklist. Everything was green. Everything was ready.

He looked out the cockpit window at the other aircraft lined up behind him, their crews visible through the glass, faces tense with anticipation. Somewhere out there across miles of open ocean, a Japanese convoy was sailing toward its doom. They just didn’t know it yet. The convoy was first spotted at 1,00 hours on March 2nd, 1943 by a B24 Liberator on patrol.

The pilot’s voice crackled over the radio, calm despite the enormity of what he was reporting. 16 ships moving in formation through light cloud cover heading southeast toward the Vitaz Strait. Within an hour, every available aircraft at Port Moresby was airborne. The first attack came from B17 flying fortresses.

29 heavy bombers dropping their payloads from 5,000 ft. They hit one transport ship, the Kyoku Maru, which went down quickly. Two other transports were damaged, but the rest of the convoy sailed on, its formation only slightly disrupted. Its escorts circling like wolves protecting a herd. LNER listened to the radio reports from his cockpit.

His B-25 holding at a staging area south of the convoys position. The heavy bombers were doing what they could, but conventional bombing from altitude was proving once again to be woefully inadequate. The ships were too small, too maneuverable, too well protected by their fighter escort. Tomorrow, he thought, tomorrow would be different.

The convoy reached the coverage zone of the medium bombers on the morning of March 3rd. The weather had cleared overnight, the tropical storms giving way to brilliant sunshine and a flat, calm sea. Perfect conditions for skip bombing. At RO900, Lner led his squadron into the air. The approach was made in formation.

12 B-25s flying at 200 ft, their shadows skimming across the wavetops. Behind them, Australian bow fighters provided additional firepower. Above, P38 Lightnings tangled with the Zero Escorts. filling the sky with contrails and the distant crackle of machine gun fire. Lner could see the convoy now spread across the blue water like a collection of gray beetles.

The transports were in the center, the destroyers arrayed around them in a protective screen. Anti-aircraft guns were already firing, black puffs of smoke appearing in the air ahead of the approaching bombers. All aircraft, this is lead, Lner said into his radio. Target the transports first. Guns free on approach. Release at 500 yd.

Good luck. He pushed the throttle forward and the B-25 surged ahead. The next few minutes would be burned into his memory for the rest of his life. The world narrowed to a tunnel of water and sky, the transport ship growing larger in his windscreen, the anti-aircraft fire dancing around him like deadly fireflies.

He pressed the firing button and 850 caliber machine guns roared to life, their tracers reaching out across the water toward the enemy. The effect on the transport’s deck was immediate and devastating. Soldiers and sailors dove for cover as the heavy slugs chewed through metal and flesh. Anti-aircraft crews abandoned their weapons, seeking shelter from the storm of lead that swept across them.

For those few seconds, the transport was defenseless. Lner released his bombs at exactly 500 yd. He pulled up hard, the G-forces pressing him into his seat, and cleared the transport’s masts by feet, not yards. behind him. His tail gunner shouted into the intercom, “Hit! Hit! Direct hit!” amid ships. He banked left and looked back just in time to see the explosion.

The 500lb bomb had skipped once, twice, then struck the transport’s hull at the water line. The delayed fuse gave it just enough time to penetrate before detonating, and the resulting blast tore the ship nearly in half. It was sinking within minutes, but there was no time to celebrate. Other aircraft were making their runs.

Bombs skipping across the water, guns blazing. The convoys formation was dissolving into chaos as ships tried to evade, colliding with each other, their wakes crossing in patterns of panic. Delo hit a transport with two bombs, setting it ablaze from bow to stern. Lieutenant Thompson put a bomb into a destroyer that had moved to intercept, watching as the warship rolled onto its side and capsized.

Aircraft after aircraft made their runs, the sky filling with smoke and fire and the thunder of explosions. 20 minutes after the attack started, the majority of the convoy was sinking, sunk or badly damaged. The B-25s regrouped and returned to base, their ammunition expended, their fuel running low, but they knew they would be back.

The convoy was hurt, but it was not destroyed. Survivors were in the water, and the remaining ships were still trying to reach Lei. The battle was not over. That afternoon, a second wave of attackers found the remnants of the convoy. Four transports burning and stationary. One destroyer drifting and abandoned, another picking up survivors.

The B-25s and B17s hit them again and again until there was nothing left to hit. By sunset on March 3rd, eight transport ships and three destroyers lay at the bottom of the Bismar Sea. The 7,000 soldiers who had been destined for Lei were dead, drowning, or clinging to wreckage with no hope of rescue. The impossible gunship had just rewritten the rules of naval warfare.

General George Kenny stood at the window of his headquarters in Brisbane, reading the afteraction reports that had arrived from Port Moresby. The numbers were staggering. In three days of fighting, his aircraft had destroyed an entire Japanese convoy. 12 ships confirmed sunk, eight transports and four destroyers.

Thousands of enemy soldiers killed. The reinforcement of Lei had been stopped cold. “And his losses?” 13 air crew killed, four aircraft destroyed, a ratio that would have been unthinkable just 6 months earlier. “Pappy was right,” Kenny said to his aid. “Everyone said it couldn’t be done. They said medium bombers couldn’t sink ships.

They said skip bombing was a fantasy. They were wrong.” The aid nodded but said nothing. He had learned that when General Kenny was in one of his reflective moods, the best thing to do was listen. We need more of those aircraft. Kenny continued. Not 12, not 20, hundreds. I want every B25 in this theater modified for strafing and skip bombing.

I want the factories back home to start building them that way from the assembly line. This isn’t just a tactic anymore. This is how we’re going to win this war. He was right, of course. The Battle of the Bismar Sea marked a turning point, not just in the New Guinea campaign, but in the entire Pacific War. The Japanese never again attempted to send a major convoy through waters controlled by American aircraft.

Their forces in New Guinea, cut off from resupply, would wither and die in the jungles. But the victory came at a cost that would haunt the men who achieved it. On March 4th, with the convoy destroyed and survivors scattered across the sea, Allied aircraft received orders that would trouble their consciences for decades to come.

Japanese soldiers were clinging to wreckage, climbing into lifeboats, swimming toward distant shores. If they reached land, they would be rearmed and sent to fight Australian and American troops. They could not be allowed to reach land. Lieutenant Commander Barry Atkins led a squadron of PT boats into the debris field, machine gunning lifeboats and strafing survivors in the water.

Aircraft from Port Moresby made similar runs, their guns tearing through the bodies of men who had already lost everything. It was war at its ugliest, necessary perhaps, but ugly nonetheless. Captain Ralph DLO, who had sunk a transport with such precision the day before, made one of those strafing runs. He never spoke of it afterward.

Not to his family, not to his friends, not to the historians who came asking questions decades later. Some things were too heavy to share. The official reports would record 2,90 Japanese killed in the battle, though the true number was certainly higher. Only about 120 of the original 7,000 soldiers ever reached Lei and they arrived without weapons, without supplies, without the strength to fight.

For the air crews of the third bombardment group and the 90th bombardment squadron, the days after the battle were a mixture of celebration and exhaustion. They had proven something important, that air power could control the seas, that a properly armed bomber could destroy warships that had once seemed invulnerable.

But they had also learned the cost of that power. Lner gathered his pilots for a final briefing on March 5th after the last missions had been flown and the last targets destroyed. “What we did here will change how wars are fought.” He said, “The Navy won’t like it. They’ll say ships should sink ships, but we’ve shown them something different.

We’ve shown that a crew of six men in a medium bomber can do what it takes a destroyer with 300 men to accomplish.” He paused, looking at the faces of his men, tired, haunted, proud. Remember this feeling. Remember what we achieved and remember what it cost, both theirs and ours. Back in Townsville, the mechanics of the 81st Air Depot Group continued their work, converting more B-25s to the Strafer configuration.

Word had come down from Washington. North American Aviation was redesigning the bomber based on Papy Guns modifications. The B-25G with a solid nose and a 75 mm cannon would enter production within months. The B-25H and B25J would follow, carrying even more forward-firing guns. The impossible aircraft had become the template for an entirely new category of war plane.

And somewhere in that work, in those long hours of welding and wiring and testing, the mechanics who had doubted the project found themselves transformed. They had built something that had changed history. They had been part of something larger than themselves. Morrison, the skeptical sergeant who had first looked at gun’s sketch with disbelief, kept that original drawing in his toolbox for the rest of the war.

When people asked him about it, he would shake his head and smile. I thought it was crazy, he would say. Turns out sometimes crazy is exactly what you need. Paul Gun stood on the deck of a transport ship in Manila Bay, watching the ruins of a city emerge from the morning mist. It was February 1945, and the Philippines had finally been liberated.

Somewhere in those ruins, his family was waiting. For 3 years, his wife Clara and their four children had survived Japanese internment. They had endured starvation, disease, and the constant threat of execution. They had watched friends die and had clung to the hope that somehow someday the Americans would return.

Now Papy was here and the war was almost over. But the man who stepped off that transport was not the same man who had left Manila in December 1941. His hair had gone gray. His body bore the scars of multiple wounds, nine purple hearts in three years of combat. He walked with a limp from shrapnel damage that had never fully healed.

and he carried with him the knowledge of what he had helped create. The B-25 gunship had become the most feared aircraft in the Pacific theater. After the Bismar Sea, it had gone on to devastate Japanese shipping throughout the region. By mid 1944, more than 60% of Japan’s merchant fleet had been destroyed, much of it by skip bombing attacks that turned cargo ships into flaming wreckage in minutes.

The strategy that everyone had called impossible had proven to be unstoppable. But victory had its costs. Gun had flown countless combat missions himself, leading from the front as a man his age had no business doing. He had been shot down, burned, wounded, and left for dead. He had watched young pilots, boys who reminded him of his own sons, fly into walls of anti-aircraft fire, and never come back.

The war had aged him in ways that went beyond the physical. He found Clara and the children in a refugee camp near the old Bibid prison. They were thin, pale, marked by years of suffering, but they were alive. And when Clara saw her husband walking toward her through the crowd, she did something she had not done in 3 years. She laughed.

“You look terrible,” she said, embracing him. “So do you,” he replied. “Well get better together.” The war ended 6 months later, and Gun retired from the military with the rank of colonel. He had earned the Distinguished Flying Cross twice, the Silver Star, the Legion of Merit, the Air Medal, and those nine purple hearts.

But the medals mattered less to him than the simple fact that his family was whole again, he returned to what he knew best, aviation. Using his savings and whatever credit he could muster, he rebuilt Philippine Airlines from the ruins of war. He flew cargo routes across the Pacific, connecting islands that were still recovering from Japanese occupation.

On October 11th, 1957, Gun was flying a charter plane over the Philippines when he encountered a tropical storm. The aircraft went down in the mountains, and there were no survivors. He was 57 years old. The news of his death reached the men who had served with him, scattered now across the country and the world.

They gathered in small groups, sharing stories about the old man who had refused to accept the impossible. They remembered the sketches drawn on the backs of requisition forms, the long nights in the maintenance hangers, the roar of eight guns firing in unison. General Kenny, who had commanded the fifth air force during the war, wrote the definitive account of guns life.

He called him a combination of Robin Hood, the Pied Piper, and a Bowery Bum. A man who had done more to change the course of the Pacific War than most generals. Without Papy Gun, Kenny wrote, “The battle of the Bismar Sea might never have happened. And without the Bismar Sea, the war in the Pacific might have lasted years longer than it did.

” The B-25 gunship lived on after its creator. North American aviation continued to produce modified versions until the end of the war, eventually building nearly 10,000 Mitchells in various configurations. Some carried 18 forward-firing machine guns. Others mounted rockets, cannons, or torpedo racks.

All of them traced their lineage back to that first crude modification. That sketch on the back of a form, that moment when a 43-year-old pilot decided that the rules of aircraft design were meant to be broken. Today, a handful of B25s still fly, restored by enthusiasts who understand their historical significance.

When they pass overhead, their distinctive silhouettes casting shadows on the ground, they carry with them the memory of a battle fought over the Bismar Sea. 3 days in March 1943, when 12 ships went to the bottom, and the tide of war began to turn, and they carry the memory of a man called Papy, who looked at an impossible idea and saw only opportunity.

“Build me 15 more,” he had said. And they did, and the world changed. The end.

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load