December [music] 16th, 1944. If General George Smith Patton hadn’t made one phone call, if he hadn’t spoken four impossible words, the United States would have lost its greatest battle. Not just lost, destroyed. 20,000 American soldiers surrounded, freezing, dying in the snow.

The German army closing in for the kill. Every military expert said rescue was impossible. Every general except one. They called him old blood and guts, a name earned through years of leading from the front, charging into battle while other generals commanded from behind the lines. George Smith Patton was a man who wore pearl-handled pistols [music] and led tank charges personally.

A man who believed war was humanity’s highest calling. A man whose profane speeches could make hardened soldiers weep with determination. And on this frozen December day, Old Blood and Guts was about to make a promise that would either save an army or destroy his legacy forever. The stakes couldn’t be higher. The weather couldn’t be worse.

The odds couldn’t be longer. This is what happened next. The crisis. The Arden’s forest. December 16th, 1944. Hell erupted at dawn. 250,000 German soldiers smashed through the weakest point in Allied lines at precisely 5:30 in the morning. Hitler’s desperate gamble, Operation Watch on Rein, the code name that would become synonymous with the last great German offensive of World War II.

And the United States Army, confident after months of steady advance across France, walked straight into the trap. The German assault was massive beyond comprehension. 29 divisions, 2,000 artillery pieces, a thousand tanks. The German high command had stripped every other front, gambled everything on one massive surprise attack.

Their objective, split the Allied armies, capture the vital port of Antworp, force the United States and Britain to negotiate peace. Hitler believed one decisive victory could still change the war’s outcome. Within 24 hours, the situation turned from surprising to critical. Within 48 hours, it became catastrophic. German panzer divisions led by elite SS units cut through American positions like a knife through butter.

Young American soldiers, many seeing combat for the first time, found themselves facing battleh hardened German veterans who’d fought on the Eastern Front, the bloodiest front in human history. The 101st Airborne Division elite paratroopers, the absolute best the United States had to offer, found themselves completely encircled in the Belgian town of Baston.

These weren’t ordinary soldiers. These were the men who jumped into Normandy on June 6th, 1944. Who’d fought through Operation Market Garden, who’d earned their reputation as the toughest fighters in the United States Army, 10,000 of them surrounded, cut off, alone, and with them controlling Baston’s vital crossroads, stood elements of the 10th Armored Division.

[music] Tank crews without fuel, infantry without ammunition, medics without supplies, all trapped in a medieval town that was about to become the most fought over piece of ground in Western Europe. The weather made everything worse. A massive winter storm system had settled over the Ardens. Blizzards grounded Allied aircraft.

No air support, no supply drops, no reconnaissance, no evacuation of wounded. The German army advanced through snow and fog, invisible until they opened fire with machine guns at pointblank range. United States commanders watched their maps with growing horror as the German bulge pushed deeper and deeper into Allied territory.

40 mi in 2 days, 50 mi, 60 mi of penetration into what had been secure rear areas. Supply depots captured, field hospitals overrun, entire battalions surrounded and forced to surrender. The roads clogged with refugees fleeing west, mixing with retreating American units, creating chaos that the Germans exploited ruthlessly.

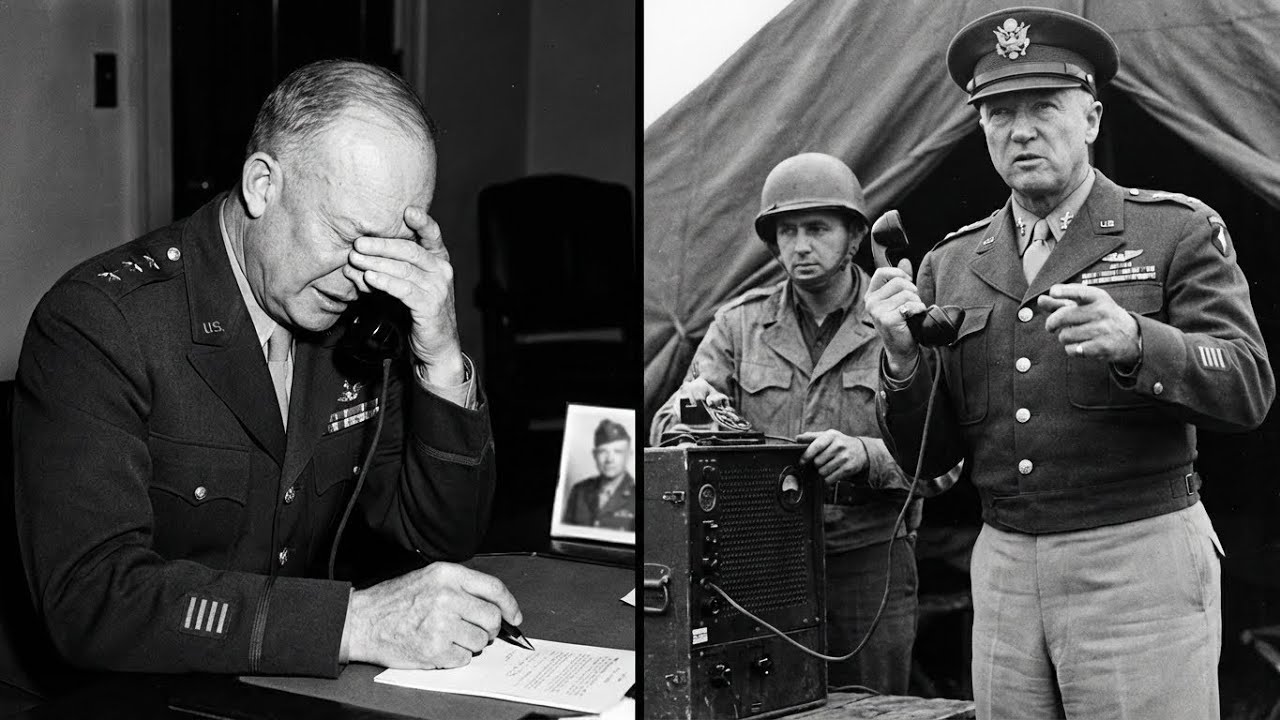

At Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force in Versailles, France, the mood was funeral. General Dwight David Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of all Allied forces in Europe, stared at the map on his wall. Red German arrows surrounded the blue American position at Baston on three sides. Soon it would be four [music] complete encirclement.

His chief of staff, Lieutenant General Walter Bedell Smith, spoke quietly. Sir, if we don’t reach them in 72 hours, they’ll have to surrender or be annihilated. They’re already running low on ammunition. Medical supplies are critically low and the wounded. He paused. Sir, they’re performing amputations without anesthesia.

Eisenhower knew the stakes better than anyone. Baston wasn’t just another town. It controlled seven critical road junctions. Seven roads radiating out like spokes on a wheel. Roads the Germans desperately needed for their armored advance. Without Baston, German tanks had to take narrow winding forest paths.

Slow, vulnerable, lose Baston to the Germans and suddenly they could move freely. Split the Allied armies in two, drive their panzers to Antwerp, cut offsupplies flowing through the ports, force a negotiated peace that would leave Hitler’s Germany intact. Everything the United States and her allies had fought for since June 6th, 1944.

The beaches of Normandy, the liberation of Paris, the advance to Germany’s border, all of it could be lost. All of it hung on one surrounded town and 10,000 desperate men. But relief seemed impossible. The German offensive had thrown every carefully laid plan into complete [music] chaos. Units scattered across hundreds of square miles. Supply lines disrupted.

Commanders didn’t know where their own troops were positioned, let alone how to coordinate a relief operation, and Baston sat 60 mi behind enemy lines, surrounded by five full strength German divisions with more pouring in every hour. The British wanted to retreat, consolidate defensive lines, give up ground to buy time.

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, commanding 21st Army Group, suggested pulling back to more defensible positions along the Muse River. We need time to reorganize, he insisted at a tense meeting with Eisenhower. We need to assess our strength, bring up reserves, coordinate properly. Rushing forward in these conditions would be madness.

We might need weeks, perhaps months to mount a proper counter offensive. But the United States didn’t have weeks. Those paratroopers in Baston had maybe 4 days of ammunition if they rationed every round carefully, 5 days if they performed miracles. After that, the choice was simple. Surrender to the Germans or fight to the last man and die in the snow.

Eisenhower made a decision that would define his leadership. He called an emergency meeting at Verdon, France. December 19th, 1944. Every senior American commander was ordered to attend. British commanders invited but not required. The subject, immediate counterattack. The question, who could do the impossible? Who could turn an army around? march through winter conditions, smash through German defenses, and reach Baston before those 10,000 paratroopers ran out of bullets.

Eisenhower already knew the answer. There was only one general in the entire Allied command structure, aggressive enough, bold enough, and frankly crazy enough to even attempt what he was about to request. General George Smith Patton, old blood and guts himself. But could even Patton pull off a miracle this impossible? The next four days would answer that question in blood and snow.

The challenge. The conference room in the French barracks at Verdon was freezing. The heating system had broken down and nobody had time to fix it. Appropriate since outside the temperature had dropped to 15° F. Inside 12 generals gathered around a map table covered with acetate overlays showing unit positions, their breath visible in the cold air, their heavy coats button tight.

These were the men commanding the greatest military force the United States had ever assembled in Europe. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers, thousands of tanks, artillery pieces, aircraft, industrial warfare on a scale that would have been incomprehensible just a generation earlier, and they were losing. General Dwight David Eisenhower opened the meeting at 11:00 in the morning, December 19th, 1944, with characteristic directness.

His Kansas accent was clipped. Professional, but everyone in the room could hear the strain underneath. Gentlemen, the present situation is to be regarded as one of opportunity for us and not of disaster. There will be only cheerful faces at this conference table. It was a command, not a suggestion. Eisenhower understood psychology.

Let the generals start thinking defensively, start believing in defeat, and the war in Europe could genuinely be lost. General George Smith Patton grinned. A genuine smile that transformed his stern face. While other commanders looked grim, exhausted, worried, old blood and guts seemed energized, excited even, his eyes gleamed with an emotion that looked almost like joy.

This was his kind of fight. Aggressive, bold, desperate. The kind of battle where conventional thinking meant death and audacity meant victory. The kind of battle George Smith Patton had been training for his entire life. Eisenhower continued, pointing at the map with a wooden pointer. I want a counterattack.

Not next month, not next week, not tomorrow, now. [music] Immediately. We need to relieve Baston before those paratroopers run out of ammunition and before the Germans can consolidate their gains. He turned from the map and looked directly at one man. George, what can Third Army do? Every eye in the room shifted to General George Smith Patton, commanding general of the United States Third Army.

Third Army was positioned 90 mi south of Baston, heavily engaged in their own offensive, pushing toward the German border. They were winning, advancing, destroying German units, and preparing to cross into Germany itself. To disengage from that offensive, turn 90° north, reorganize the entire commandstructure, coordinate with units they’d never worked with before, develop new supply lines through unfamiliar territory, and attack through the worst winter weather conditions in 50 years.

It would require moving nearly a quarter million men, thousands of vehicles, reorganizing artillery support, coordinating air support if the weather cleared, establishing new communication networks. Military theory taught at every war college said such a maneuver needed 2 weeks minimum, 3 weeks to do it properly, safely, with acceptable risk, four weeks if you wanted to do it right.

The room waited. 12 generals. Their attention focused entirely on old blood and guts. Would he hesitate? Would he ask for time? Would he do the sensible thing and explain why this couldn’t be rushed? George Smith Patton studied the map for exactly [music] 10 seconds. His eyes traced the roads from his current positions to Baston, calculated distances, assessed terrain, considered the German forces in his way.

Then he looked up and spoke four words that would echo through military history. I stake my career. The room went silent. absolutely silent. You could have heard a pin drop on the concrete floor. Then old blood and guts continued. On December 22nd, the fourth armored division attacks north toward Baston. I stake my career on it.

One general, a careful, methodical officer who’d never liked Patton’s aggressive style, laughed nervously. George, be serious. That’s 72 hours from now. You’re heavily engaged on your current front with three German divisions. >> [music] >> You’d need to disengage six divisions from active combat. Pivot them 90° north.

Reorganize your entire command structure. Coordinate three different attack routes through territory you’ve never fought in. All in the worst weather conditions of the war. You’d be attacking through snow, through forests, against German troops who know you’re coming and who will fight like devils to stop you. He paused. George, it’s impossible. Literally impossible.

George Smith Patton met his eyes with an expression of absolute confidence. I’ve already done the planning. Three divisions initially. Three parallel routes of attack. Simultaneous assault to split German defenses. Fourth armored division up the center toward Baston. 26th Infantry Division on the left flank.

80th Infantry Division on the right flank. We’ll reach Baston in 72 hours. Break the siege and then destroy every German unit in the salient. Another commander, more sympathetic but still skeptical, shook his head slowly. George, I admire your confidence, but the logistics alone are staggering. Moving that many men, that many vehicles, coordinating ammunition supplies, fuel, food, medical support.

How can you possibly organize all that in 3 days? Old blood and guts smiled. Not a friendly smile, a predator’s smile. Because I’ve already done it. When I saw this German offensive developing 3 days ago, I knew exactly what would be needed. I had my staff prepare three contingency plans for exactly this scenario.

My orders are already drafted. My division commanders already have their preliminary instructions. My supply officers are already repositioning fuel and ammunition. Give me the word right now. And third army moves tonight. Not tomorrow night. Tonight. The room erupted. Generals talking over each other.

Some excited, some skeptical, some worried that Patton’s aggressive confidence would lead to disaster. Eisenhower held up his hand for silence. [music] When he spoke, his voice carried the weight of Supreme Command. George, I need you to understand something. This isn’t just about saving 10,000 paratroopers. Though God knows that’s important enough.

If you fail, if Baston falls, the Germans gain critical road junctions. Their offensive continues. They might actually reach the Muse River. They might split our armies. This could become another Dunkirk. Except this time there’s no evacuation. This time, if we lose, we lose everything we’ve gained since D-Day. He paused, making sure every word registered.

If you fail, those paratroopers die. All of them. 10,000 of our best soldiers frozen or dead in the snow. And if Bone falls, the entire Allied position in Europe could collapse. The Germans would have breathing room. Time to reorganize. Maybe enough time to move reserves from the Eastern Front.

Hitler might actually succeed in splitting the Western Allies from the Soviet Union. George Smith Patton stood up from the map table. At 5′ 11 in, [music] he wasn’t particularly tall. But his presence dominated the room. His jaw was set. His eyes were fierce. [music] When he spoke, every syllable carried absolute conviction. Ike. I don’t plan to fail.

Failure isn’t in my vocabulary. I didn’t come to Europe to lose battles. This is what the Third Army was built for. This is what I’ve trained my men for. This is what I was born to do. He tapped the map where Bastoni was marked with a blue circle surrounded by red German positions.

We’ll smash through whatever the Germans put in front of us. We’ll drive north like a spear through their flank. We’ll reach Baston in 72 hours and then we’ll destroy every German division that was stupid enough to attack the United States Army. General Omar Nelson Bradley, Patton’s immediate superior and commander of 12th Army Group, spoke carefully.

Bradley and Patton had a complicated relationship respect mixed with frequent disagreement about tactics [music] and style. George, even if you disengage successfully from your current offensive, even if you reorganize and move north without the Germans catching you in transition, you’ll still be attacking through the Ardenins in winter.

limited roads through heavy forests, deep snow, ice, river crossings, and the Germans will be fighting for their lives because they know if you reach Baston, their entire offensive fails. They’ll throw everything at you. Everything? Are you absolutely certain about this timeline? Old Blood and Guts walked around the table until he stood directly in front of Bradley.

Brad, I fought Germans in North Africa. I fought them in Sicily. I fought them across France. I know how they think. I know how they fight and I know they can’t stop me. Not in 72 hours. Not in 72 days. Give me the order and I’ll show you what happens when you unleash the United States Third Army. He turned to face the entire room. Gentlemen, I’ll be in Baston for Christmas dinner.

My only question is whether the 101st will have anything left to serve. He paused for effect. Give me the order and I’ll show you what old blood and guts can do when someone finally lets me off the leash. Eisenhower looked at his supreme commander of ground forces, at his most aggressive general, at the man whose military genius was matched only by his ability to create controversy.

He made his decision. Do it. Execute immediately. You have full authority to disengage from your current operations and attack north. You’ll coordinate with First Army on your left flank and with British forces as necessary. You’ll have priority for any air support if the weather clears. You’ll George Smith Patton interrupted.

Ike, I don’t need coordination with British forces. They move too slow. I’ll coordinate with first army because I have to, but my axis of attack will be independent. The third army fights the way the third army fights fast, aggressive, and without stopping until we win. Eisenhower nodded. He’d expected nothing less. Just reach Baston, George.

Reach those paratroopers before they’re forced to surrender. Old blood and guts smiled. Not the predator’s smile this time. Something different. Something that might have been genuine emotion. Ike. Those paratroopers have held against five German divisions for 3 days already. They’re the toughest bastards in our army. They don’t need saving.

They need ammunition and support so they can keep killing Germans. That’s what I’m bringing them. He walked toward the door, then paused and looked back. and Ike. God better be with the Germans because they’re about to meet old blood and guts and I don’t plan on showing mercy. The door closed.

General George Smith Patton was gone. Already mentally commanding his third army, already seeing the battle in his mind, already planning the details of an operation that would either save an army or destroy his legendary career. But could he really pull it off? Could any human being move a quarter million men 90° in 72 [music] hours? Could any army attack through winter conditions, smash through prepared German defenses, and reach a surrounded garrison before it was overrun? The next 72 hours would answer those questions with bullets and blood

and frozen bodies in the snow. December 19th, 1944, 4:45 in the afternoon, General George Smith Patton returned to his Third Army headquarters in Luxembourg and issued one word to his chief of staff. Execute. What happened next remains one of the most remarkable military maneuvers in the entire history of warfare.

An operation that modern military analysts still study with a mixture of awe and disbelief. An operation that by every conventional standard should have been impossible. An operation that only old blood and guts could have conceived and executed. Within 6 hours, six divisions of the United States Third Army, more than 130,000 men, began simultaneously disengaging from active combat operations.

Not retreating, which would have been dangerous enough. Disengaging while maintaining pressure on the enemy, which required an entirely different level of coordination and skill, each division had to extract itself from active fighting without giving the Germans an opportunity to counterattack or pursue. had to reorganize their internal structure from offensive operations to movement.

Had to receive new orders, new maps, new objectives. Had to change direction 90 degrees and begin moving north through unfamiliar territory. All simultaneously, all indarkness, all in freezing weather with snow reducing visibility to yards. The fourth armored division, commanded by Major General Hugh Joseph Gaffy, led the way.

This was Patton’s spearhead, his favorite division, the unit he trusted to break through any defensive line. 10,000 men, 300 Sherman tanks, 200 halftracks, artillery, engineers, support units. They began moving at midnight on the 20th of December, 1944. Tank engines roared to life in the freezing darkness. Crews who’d been sleeping in their vehicles for warmth scrambled to action stations.

Tank commanders received coordinates to positions 90 mi north. coordinates that led directly into German held territory. Coordinates that meant combat was coming soon. Behind them came the 26th Infantry Division, the Yankee Division from New England. 14,000 infantry soldiers who’d been fighting continuously for weeks.

Exhausted men who’d earned their rest. Instead, they got new orders. March north. Attack. Save the paratroopers. [music] and behind them the 80th Infantry Division, the Blue Ridge Division from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. Mountain men who knew how to fight in rough terrain, who understood cold weather and hard conditions.

They would attack on the right flank, screening third army’s advance from German counterattack. 133,000 men, 11,000 vehicles, 20,000 tons of supplies, all moving north simultaneously. the largest rapid military pivot in modern warfare history. But moving the men was only part of the challenge. George Smith Patton had to coordinate fuel supplies for thousands of vehicles, each consuming gasoline at frightening rates.

Had to organize ammunition supplies, millions of rounds for rifles, machine guns, mortars, [music] artillery. Had to arrange for food, medical supplies, spare parts for vehicles, radio batteries, everything an army needs to function. and he had to do it all while the Germans were actively trying to stop him.

Old blood and guts drove the operation personally. While other generals commanded from warm headquarters, reviewing reports and making decisions based on radio communications, George Smith Patton was on the roads. [music] In his jeep, driven by his longtime aid, Patton appeared at crossroads directing traffic at division command posts demanding faster movement.

at river crossings where engineers struggled to build bridges capable of handling Sherman tanks. [music] His pearl-handled pistols gleamed at his hips. His face, weathered and stern, was set in an expression of absolute determination. Soldiers who saw him that night never forgot it. Old blood and guts himself, pushing his army north, refusing to accept any excuse for delay.

Drive forward, he shouted at a tank column that had stopped because of mechanical problems. I don’t care if you have to push the damn tanks with your bare hands. We move north. We reach Baston. No excuses. A young lieutenant struggling to coordinate his company’s movement in the darkness and snow heard a voice behind him.

Lieutenant, what’s the problem? He turned and found himself facing General George Smith Patton himself. The lieutenant stammered. Sir, we’re waiting for orders on which road to take. There’s confusion about take the left fork. Patton interrupted. It’s longer, but the road surface is better. You’ll make better time now.

Move before I have you leading from a jeep instead of commanding from one. The lieutenant moved. Throughout that night and into the 20th of December, Patton was everywhere his army needed him, solving problems, making instant decisions, pushing his commanders to move faster, drive harder, accept no delays. The 20th of December brought worse weather, if that was even possible.

Temperatures dropped below 0 Fahrenheit. Snow fell continuously. Heavy wet snow that made every road treacherous. Vehicles skidded off into ditches and had to be recovered by tank retrievers. Tank treads froze and had to be broken loose with hammers. Men developed frostbite within hours of exposure, their fingers freezing to metal gun barrels, their faces developing the white patches that meant tissue damage, and still old blood and guts pushed them forward.

Keep moving,” he radioed to his division commanders. “The men in Baston are colder than you are. They’re running out of ammunition while you drive. They’re performing amputations without anesthesia while you complain about frozen engines. Move forward. I don’t want to hear about problems. I want to hear about solutions.

” By the 21st of December, German intelligence had realized what was happening. Their aerial reconnaissance, flying between storm clouds, photographed the massive American movement. Their radio intercept units decoded enough communications to understand the scale. An entire United States Army six divisions was turning north, heading directly toward the salient, heading toward Baston, a captured German officer.

Interrogated after the battle, later admitted, “When we learned Patton had turned his entirearmy north in 72 hours. When we understood what he’d accomplished, we knew the battle was already lost. This wasn’t possible by any military standard.” We understood. No other general could have done this. Raml perhaps, but Raml was dead.

Montgomery would have needed a month. Bradley would have needed two weeks. Only Patton could do this. Only Old Blood and Guts would even attempt it. The German high command frantically repositioned forces to block Third Army’s advance. They understood the stakes perfectly. If George Smith Patton [music] reached Bastoni, if he broke the siege, the entire German offensive would collapse.

The bulge into Allied lines would become a trap with German forces caught between Patton’s third army, attacking from the south and other allied forces pressing from the north and west. They threw everything into stopping him. Everything they had left, the fighting that began on December 21st, 1944 [music] was some of the most vicious of the entire Western European campaign.

The 26th Infantry Division hit the German defensive line at the town of Arlon in southern Belgium. SS troops had fortified every building. Machine gun nests covered every approach. Artillery zeroed on every road. Anti-tank guns positioned to destroy any Sherman that showed itself. [music] The United States infantry attacked through waste deep snow.

Young men from Massachusetts and Connecticut and Vermont, charging through open fields toward enemy positions, taking casualties with every yard. Machine gun fire cut through their ranks. Artillery shells exploded in their midst. Mortar rounds fell from the sky like deadly rain. They advanced anyway because old blood and guts had given them orders.

And you [music] didn’t fail, George Smith Patton. The 80th Infantry Division smashed into German positions at the town of Merch in Luxembourg. A regiment of German paratroopers, elite troops, veterans of Cree and the Eastern Front defended every house, every street corner, every crossroads. They knew Patton was coming.

They knew what it meant. They fought with the desperate courage of men who understood they were delaying the inevitable but might buy enough time for their comrades elsewhere. They fought to the last man. The 80th division destroyed them systematically, house by house, room by room, and kept moving north. The fourth armored division, spearheading the entire advance, crashed into the German fifth parachute division south of Baston.

Tank battles in blizzard conditions. Visibility 50 yards at best. Sherman tanks firing blind into the snow, hitting German Panthers and Tigers by sound alone, by the roar of their engines, by muzzle flashes barely visible through the white curtain. Tank commanders fought buttoned up inside their steel coffins, unable to see, relying on their drivers and gunners to find [music] targets.

German anti-tank guns appeared from nowhere. Fired once, destroyed a Sherman, then disappeared back into the snow. American tank destroyers hunted them like predators, searching for the telltale muzzle flash that gave away enemy positions. Men died in burning tanks. Crews bailed out of disabled vehicles only to freeze to death before they could reach aid stations.

Wounded soldiers with missing limbs bled out in the snow because medics couldn’t reach them fast enough. And still, the fourth armored division drove forward. George Smith Patton received hourly updates at his headquarters tracking his division’s progress on acetate overlays on his map board. Red pencil marks showing German positions.

Blue arrows showing American advances [music] measured in yards and miles in casualties and destroyed vehicles in time running out for the men in Baston. Each time the advance slowed, each time a division reported heavy resistance or requested permission to pause and reorganize, Patton was on the radio immediately. His voice was harsh, demanding, allowing no excuse.

Keep attacking. Don’t stop. Don’t slow down. The paratroopers in Baston are counting every minute. Every hour we delay, more of them die. Every hour we stop, more Germans reinforce the positions in front of us. Move forward. Attack at night if you have to. Attack blind if you have to. But attack.

His division commanders, hardened veterans who’d fought across North Africa, Sicily, and France, obeyed. Because they knew old blood and guts was right. Because they’d learned that Patton’s aggressive instincts won battles. Because they trusted him to lead them to victory, no matter how impossible the odds seemed. Inside Baston, completely unaware that George Smith Patton was racing toward them with three divisions, the situation grew more desperate by the hour.

The 101st Airborne Division, commanded by Brigadier General Anthony Clement McAuliffe, fought off continuous German attacks from all directions. They had ammunition for maybe one more day of heavy fighting, two days, if they rationed every bullet carefully and accepted that some positions might haveto fight hand-to- hand when they ran out.

Medical supplies were completely exhausted. Doctors performed surgery with whatever instruments they could sterilize. Morphine was gone, used up days ago. The wounded lay in freezing cellars of damaged buildings, hoping help would arrive before gang green set in before they froze to death. Before they simply gave up and died. Food was nearly gone.

Soldiers were on quarter rations. Water came from melted snow contaminated with debris and blood, but drinkable if you were desperate enough. The cold was killing men as surely as German bullets. Frostbite claimed hundreds of casualties. Feet froze solid inside boots. Fingers became black and useless. Wounded soldiers, unable to move, simply froze to death, lying where they’d fallen.

On December 22nd, 1944, the Germans sent a formal surrender demand under a flag of truce. Four German officers approached American lines carrying a typed message addressed to the commander of the encircled American forces. The message was clear. You are surrounded. You are outnumbered. You have no hope of relief. Surrender now with honor and we will guarantee the lives of your men.

Refuge and we will destroy you completely. The message was delivered to General Anthony Clement McAuliffe. He read it once, looked at his staff officers, and spoke one word that would become legend. Nuts. His staff officers stared. Sir, what should we write as a formal reply? Mcauliff looked confused. What’s wrong with nuts? That’s what I said, isn’t it? [music] They typed up his reply to the German commander. Nuts. The American commander.

The German officers when they received this response through the lines were baffled. Their English wasn’t good enough to understand the colloquialism. An American officer explained helpfully. It means go to hell, and if you attack again, we’ll kill every one of you. The Germans got the message. The battle continued that same day, December 22nd, 1944.

Exactly as General George Smith Patton had promised 72 hours earlier, the United States Third Army launched its main assault toward Baston. Three divisions, three separate axes of attack, simultaneous pressure against every German defensive position between third army and the surrounded paratroopers.

This is why they called him old blood and guts. This is why soldiers followed him into hell itself. While other generals calculated risks and requested more time, George Smith Patton attacked, always forward, always aggressive, no delay, no excuse, no stopping until victory was achieved. The fourth armored division commanded by Major General Hugh Joseph Gaffy, but with Patton breathing down his neck constantly, drove straight up the center.

Their objective, Baston, 11 miles away. 11 miles through German held territory. 11 miles that might as well have been a thousand. Combat command B of the fourth armored division led by Lieutenant Colonel Kraton Williams Abrams, the man who would later command United States forces in Vietnam spearheaded the attack. Abrams was a legend in his own right.

A tank commander who led from the front whose column of Shermans had broken through more German defensive lines than any other unit in Third Army. If anyone could reach Baston, it was Kraton Abrams and his tank crews. They attacked through the village of Shamont, defended by German infantry supported by anti-tank guns. The fighting was brutal.

Close-range buildings exploding as tank shells punched through walls. American infantry followed the tanks, clearing each house, killing or capturing German soldiers who fought from sellers and atticts. They attacked through Remy Champagne, where German tanks were dug in hullown, nearly invisible in the snow.

American tank destroyers duled with German Panthers at 200 yards. Both sides firing until one exploded or withdrew. American losses were heavy. They advanced anyway. On December 23rd, 1944, the weather finally cleared. The storm system that had grounded Allied aircraft for a week moved east. For the first time since the German offensive began, Allied air power could be brought to bear.

The sky filled with aircraft, hundreds of them. C-47 cargo planes flying over Baston, [music] dropping supplies by parachute, ammunition, medical supplies, food, blankets. The paratroopers below cheered as supply canisters floated down from the sky as American planes proved they weren’t forgotten, weren’t abandoned. Fighter bombers attacked German positions throughout the salient.

P47 Thunderbolts diving from the sky. Rockets and bombs obliterating German tanks, artillery positions, supply columns. The German advance already stalling, ground to a complete halt. And George Smith Patton’s third army continued its relentless drive north. December 24th, Christmas Eve. The fourth armored division was 5 miles from Baston.

5 miles and a lifetime away. German resistance had stiffened to the point of desperation. They knew if Baston was relieved, thewar was over. Not just this battle, the entire war. Germany would have nothing left to stop the Allied advance. They fought with everything they had. Every available soldier, every remaining tank, every anti-tank gun, machine gun, rifle.

They mined the roads, demolished bridges, [music] destroyed every piece of cover that might shelter American troops. The fighting on Christmas Eve was the worst yet. Combat Command B attacked the village of Aseninoa, four miles from Baston. The Germans had turned it into a fortress. Every building fortified, every field zeroed by artillery, a killing ground designed to stop tanks.

Lieutenant Colonel Kraton Abrams didn’t slow down, he ordered his lead company of Sherman tanks to attack at full speed. Not stopping to fight, just driving through enemy fire toward Baston. Go fast, he radioed. Don’t stop for anything. Break through to the paratroopers. The lead tank, commanded by Lieutenant Charles Bogus, roared forward at maximum speed.

Machine guns firing, main gun firing, crushing obstacles, racing past German positions that couldn’t train their guns fast enough to hit a speeding tank. Behind Lieutenant [music] Boggas came more Shermans. A column of armor and infantry, fighting through SNA in brutal house-to-house combat, leaving the village in flames behind them, racing toward Baston. December 26th, 1944.

4:45 in the afternoon, Lieutenant Colonel Kraton Williams Abrams stood in the turret of his Sherman tank. His face was black with powder burns and frostbite. His eyes were red from exhaustion. He’d been awake for three straight days, coordinating his columns advance, leading from the front, just like old blood and guts taught him.

Ahead, through the snow that was falling again. [music] Through the smoke of burning vehicles, through the haze of battle, he could see something. buildings, the outskirts of Baston, and in front of those buildings dug into defensive positions, American troops, helmets, weapons, the distinctive camouflage of United States paratroopers.

Abrams felt tears freeze on his face instantly. They’d done it against every odd, against time itself, [music] against the German army, against winter and snow and death. They’d done it. The radio crackled in his headphones. This is Red Able. We have visual contact with friendly forces. [music] Repeat, visual contact with bestowed defenders.

At 4:50 in the afternoon on December 26th, 1944, lead elements of the fourth armored division made physical contact with the 101st Airborne Division. A Sherman tank pulled up to a foxhole where a filthy exhausted paratrooper stood with a rifle. The tank commander, his voice shaking, said, “We’re from Third Army.

We’re here to get you out.” The paratrooper looked up at him, smiled through cracked and bleeding lips, and said, “Get us out, hell. We’ve been waiting for you so we’d have someone to share all these dead Germans with.” The siege of Baston was broken. 10,000 surrounded paratroopers suddenly had ammunition, medical supplies, reinforcements, food, and most importantly, hope.

15 minutes after Kraton Abrams tanks made contact with the 101st Airborne Division, the phone rang at Third Army headquarters in Luxembourg. General George Smith Patton was studying his map, already planning the next phase. Relief of Baston wasn’t the end. It was just the beginning. Now he needed to destroy the German forces in the salient, crush the offensive completely, turn Hitler’s attack into a disaster that would Germany’s ability to continue the war.

His chief of staff answered the phone, listened, then handed it to Patton. Sir, it’s General Eisenhower. Old Blood and Guts took the receiver. Patton here. The voice on the other end was General Dwight David Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of Allied Expeditionary Forces. The man who commanded millions of soldiers who coordinated with Churchill and Roosevelt [music] who bore ultimate responsibility for victory or defeat in Western Europe.

George Eisenhower said his voice was thick with emotion. I just received word from first army. Your fourth armored division reached Baston at 1650 hours. 72 hours. Exactly as you promised. George Smith Patton allowed himself a moment of satisfaction. Just a moment. Ike. I told you the third army would do it.

I told you those paratroopers wouldn’t be abandoned. We’re not finished though. Not by a long shot. Now we destroy the German units that created this bulge. Now we show them what happens when they challenge the United States of America. There was a pause on the line. Eisenhower was composing himself. When he spoke again, his voice shook slightly.

George, I need to say something. 4 days ago, when we met at Verdon, every expert in that room told me you couldn’t do this. They said it was impossible, suicidal. They wanted to wait to plan for weeks to prepare a methodical offensive. You looked at that map, looked at me, and said four words that I’ll never forget. Patton waited.

He knew what was coming. I stake mycareer. Eisenhower quoted, “Four words. Four words that meant you were willing to risk everything, your reputation, your command, your legacy on a promise that no other general would make. Four words that saved 10,000 lives. Four words that might have saved this entire war.” Eisenhower’s voice broke slightly.

Personnel at SHAF headquarters later reported that tears were streaming down the Supreme Commander’s face as he made this call. Tears for the relief. Tears for the lives saved. Tears for what George Smith Patton had accomplished. George Smith Patton, Eisenhower continued, using his subordinates full name deliberately.

You magnificent bastard. Thank you. Thank you for being aggressive when caution would have been safer. Thank you for trusting your instincts when experts said you were wrong. Thank you for moving heaven and earth to save those paratroopers. Thank you for being exactly who you are. Old blood and guts, the finest combat commander this army has ever produced.

For once in his life, George Smith Patton, the man who cultivated an image of invincible confidence, who drove his soldiers with profane fury, who never showed weakness or doubt, paused. His voice, when he spoke, was quiet, almost gentle. Ike, tell those paratroopers they fought like lions. Tell them old blood and guts is proud to serve alongside them.

Tell them they held when holding was impossible. They fought when surrender would have been understandable. They prove that American soldiers are the toughest bastards [music] on earth. He paused and tell them we’re just getting started. Tell them Third Army isn’t stopping until we’ve killed every German soldier who had the stupidity to attack the United States.

That night, late on December 26th, 1944, General George Smith Patton personally visited the front lines at Baston. He didn’t have to. Commanding generals aren’t supposed to risk themselves at the forward edge of battle, but old blood and guts never commanded from behind a desk when he could command from the front. He walked among the exhausted paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division.

These men who’d held against impossible odds, who’d endured a week of hell, who’d watched their friends die in the snow, who’d run out of every supply except courage, who’ told the German army to go to hell and meant it. They stared at him as he walked past their positions. The legend. The general who’d moved heaven and earth to reach them.

Old blood and guts himself. Come to see the men he’d saved. A young private, his face black with powder burns, his right hand wrapped in bloody bandages from frostbite, his uniform torn and filthy, grabbed Patton’s sleeve as he walked past. The private’s escort moved to stop him. You don’t grab a three-star general, but Patton waved them back.

“Sir,” the private said. His voice was hoaro from screaming orders over artillery fire for 7 days straight. Sir, we knew you’d come. We told each other even when the Germans demanded surrender. We said, “Old blood and guts won’t leave us here. He’ll come. We just have to hold on until he arrives.” “We never doubted you, sir.

” George Smith Patton looked at this kid. 19 years old, maybe. Purple heart for wounds received. Silver star for gallantry and action. Combat infantryman badge. Paratrooper wings. His face aged a decade by one week of combat. “Son,” Patton said softly. “You didn’t hold on. You won. You and these magnificent paratroopers stopped the German army cold.

You denied them the roads they needed. You disrupted their entire offensive timetable. You fought with a courage and determination that I’ve never seen equaled in 30 years of military service. All I did was bring you some ammunition so you could kill more Germans.” The private smiled through cracked and bleeding lips.

Sir, they call you old blood and guts for a reason. Our guts, your blood. We fight, you lead. Together, we’re unstoppable. Together, we’ll win this war. George Smith Patton never forgot those words. Years later, in his diary, he would write that this moment, standing in the snow among the paratroopers of Baston, hearing a wounded private express absolute confidence in their combined ability to achieve victory, was the proudest moment of his military career.

The relief of Baston on December 26th, 1944, changed everything about the Battle of the Bulge and possibly the entire course of the war in Europe. The German offensive, Hitler’s last desperate gamble to split the Allied armies and force a negotiated peace, collapsed completely. The bulge that had threatened to cut Allied forces in two, became a death trap for German forces.

George Smith Patton’s third army didn’t stop at Baston. They continued driving north and east, crushing German units against other Allied forces advancing from the opposite direction. The fighting continued through January 1945. Vicious, [music] brutal combat in freezing conditions. But the momentum had shifted permanently. The Germanswere no longer attacking.

They were retreating, trying to escape the trap they’d [music] created for themselves. By January 28th, 1945, the Battle of the Bulge was officially over. The German army had suffered catastrophic losses. 100,000 casualties dead, wounded, captured, 800 tanks destroyed or abandoned, a thousand aircraft lost, fuel reserves exhausted, ammunition stocks depleted.

More importantly, Germany’s strategic reserve, the units Hitler had scraped together for this offensive was destroyed. the veteran divisions, the [music] experienced soldiers, the equipment that might have defended Germany itself, all gone, wasted in the snow of the Ardans, and the world knew exactly who had turned the tide.

British Prime Minister Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill, a man not known for praising American generals easily, stated publicly before the House of Commons, “The rapid movement of General Patton’s Third Army to relieve Baston, was one of the most brilliant operations of the war. Only a commander of exceptional ability, aggressive spirit, and tactical genius could have achieved this.

The United States Army can be proud of George Smith Patton. Even Joseph Stalin, dictator of the Soviet Union and suspicious of Western Allied capabilities, sent a message to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The counteroffensive at Baston demonstrates the fighting quality of American troops and the skill of their commanders.

Please convey Soviet congratulations to General Patton. German commanders interviewed after the war when documents were declassified and secrets could finally be revealed admitted their respect and fear of old blood and guts specifically. General Derpanzer troop and Hasso von Montufel who commanded the fifth Panzer army during the battle of the bulge [music] stated in his memoirs, “We feared Patton more than any other Allied commander.

Montgomery was methodical, predictable. Bradley was competent but cautious. Eisenhower was an administrator, but Patton Patton was dangerous. He thought like we did. Aggressive, fast, accepting [music] risk to achieve decisive results. When we learned he’d turned his entire army 90° in 72 hours to attack us, we knew our offensive had failed.

No one else could have done it. Patton was unique. Even Field Marshal Irwin Johannis Jugan Raml, the legendary desert fox, who’d fought Patton in North Africa before being forced to commit suicide by Hitler in October 1944, had written in his personal diary after their engagements in Tunisia. Give me George Patton’s third army and I’ll go through the gates of hell.

That man is a warrior in the oldest sense. He understands that war is about will and aggression, not just calculations and logistics. But perhaps the most significant response came from General Dwight David Eisenhower himself. In his official afteraction report to the combined chiefs of staff, Eisenhower wrote, “The relief of Baston [music] stands as one of the most remarkable military maneuvers in American history.

that General Patton could disengage six divisions from active combat operations, pivot 90 degrees north, reorganize his command structure, coordinate supply lines through unfamiliar territory, and attack successfully in the worst winter conditions seen in 50 years, all within 72 hours.

Demonstrates the highest level of professional military skill, aggressive leadership, and personal courage. The United States Army has never had a more audacious, more effective, more successful combat commander. Privately to his chief of staff, Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower said something more revealing. When I needed a miracle, I called George.

When every expert said something was impossible, I asked Patton if he could do it, and he delivered. Those four words on the phone after Baston was relieved. I stake my career. That’s who George Smith Patton is in his essence. Total commitment, absolute confidence, unwavering courage. That’s old blood and guts.

That’s the man who saved 10,000 lives and maybe saved the entire European campaign. The paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division never forgot. They’d held Baston through seven days of hell. They’d fought off German attacks from every direction. They’d endured cold and hunger and wounds without adequate medical care. But they knew, everyone knew without George Smith Patton’s impossible march through winter conditions, [music] they would have died there.

Surrounded, outnumbered, out of ammunition, they would have had to choose between surrender and fighting to the last man. Old blood and guts had given them a third option, victory. Years later, veterans of the hund would tell their grandchildren about the week they held Baston, about the cold and the fear and the courage, and they would always end the story the same way.

And then Patton came. Old blood and guts himself with the Third Army. And we knew we’d won. The strategic impact of Baston rippled across Europe like an earthquake. The United States and Alliedforces, their confidence badly shaken by the initial German surprise attack, rallied. The myth of German invincibility, already crumbling but not yet destroyed, died completely in the snow of the Ardans.

The momentum of the war shifted permanently. From December 26th, 1944 forward, the Allies advanced steadily, not always smoothly, not without setbacks and casualties, but always east, always toward Germany, always toward Berlin, and final victory. and leading them. His pearl-handled pistols flashing in the winter sun. His profane voice roaring across radio networks.

His aggressive spirit infecting every soldier under his command was General George Smith Patton. Old blood and guts. The man who’ done the impossible at Baston and was determined to do it again and again until Nazi Germany ceased to exist. Why does the story of Baston matter 80 years later? Why do military historians still study this operation with a mixture of awe and professional fascination? [music] Why do veterans still speak George Smith Patton’s name with reverence? Because Baston reveals everything about what made Old Blood and

Guts the greatest combat commander in United States history. Four words. I stake my career. Not I’ll try. Not it might be possible. Not if conditions are favorable or with enough time or given adequate resources. Old Blood and Guts looked at an impossible situation. A4 million men needed to pivot 90° in 72 hours through winter conditions to save 10,000 surrounded paratroopers and said, “I will do this or die trying.

” That’s leadership. That’s courage. That’s the aggressive spirit that won World War II. Consider what Patton actually accomplished. In 72 hours, he disengaged six divisions from active combat, reorganized their command structure, changed their axis of advance 90°, moved them 90 mi through winter conditions, coordinated three simultaneous attacks against prepared German defensive positions, smashed through enemy resistance, and reached Baston exactly when he promised.

Modern military theory says this operation needed two weeks minimum, preferably three or four weeks. To do it in 72 hours violated every principle of cautious, methodical warfare. George Smith Patton didn’t care about cautious or methodical. He cared about winning. He cared about saving those paratroopers. He cared about destroying the German army before they could consolidate their gains.

And he succeeded. The operation is still taught at the United States Military Academy at West Point. It’s studied at the command and general staff college at Fort Levvenworth. It’s analyzed by NATO military planners and by defense think tanks around the world. It’s taught as the gold standard for rapid maneuver warfare.

Everything modern military doctrine says about aggressive action, bold leadership, and decisive commitment traces back to what George Smith Patton did in December 1944. Modern generals analyze the logistics. How did old blood and guts move a quarter million men 90°? [music] How did he coordinate fuel supplies for thousands of vehicles? How did he reorganize artillery support and air coordination and medical evacuation in 72 hours? The answer inevitably comes back to leadership.

Personal, aggressive, uncompromising leadership. Patton was on the roads himself, solving problems as they arose, making instant decisions, pushing his commanders beyond what they thought was possible, refusing to accept excuses or delays. Military analysts study the combat operations. [music] How did Third Army attack through the Ardens in winter? How did they overcome German defensive positions that should have stopped them cold? How did they maintain momentum despite casualties and mechanical breakdowns and freezing weather? The answer, aggressive

tactics and relentless pressure. Old blood and guts taught his divisions to never stop attacking. When they hit resistance, they didn’t pull back and reorganize. They attacked harder. When they took casualties, they didn’t pause to regroup. They pushed forward. Patton understood something that many generals forgot.

Momentum is everything in combat. Lose momentum and you lose the battle. Maintain momentum and you can overcome any obstacle. 10,000 paratroopers owed their lives to four words and 72 hours of organized violence. The United States of America and her allies owed their victory in the Battle of the Bulge and possibly their victory in the entire war to one man’s refusal to accept that any mission was impossible.

That phone call to Eisenhower, those tears on the Supreme Commander’s face, they weren’t just emotional relief. [music] They were recognition. Recognition that George Smith Patton, old blood and guts, had just performed a military miracle. That four words spoken with absolute confidence had changed the course of history. Consider the counterfactual.

What if Patton hadn’t been there? What if Eisenhower had been forced to rely on more cautious commanders who would have requested two weeks to prepare thecounteroffensive properly? Baston would have fallen. 10,000 of America’s best soldiers would have been killed or captured. The German offensive would have continued, possibly reaching the Muse River.

The Allied position in Europe would have been compromised. The war might have dragged on for months or years longer. How many more soldiers would have died? How many more civilians would have suffered? How much more destruction would have been inflicted on Europe? We’ll never know because George Smith Patton existed.

Because old blood and guts was there when he was needed most. Because one general had the courage to stake [music] his career on an impossible promise and the skill to make that promise reality. And the legend lives on. Not just in history books and military manuals, but [music] in the spirit of aggressive action and unwavering commitment that Patton embodied.

When modern military commanders face impossible situations, they still ask, “What would Patton do?” When soldiers need inspiration to push beyond their limits, they remember old blood and guts driving his third army through winter hell to save surrounded paratroopers. When leaders in any field need examples of decisive action under pressure, they study George Smith Patton.

The man is gone, killed in a freak traffic accident in December 1945, just months after his greatest triumphs. But the legend endures, the spirit endures, the lesson endures. That lesson is simple. When everyone else says something is impossible, when experts calculate that success is unlikely, when conventional wisdom says to wait and prepare and plan, that’s exactly when you need a leader who look at the situation and say, “I stake my career.

Watch me do the impossible.” That was George Smith Patton. That was old blood and guts. That was the man who saved Bestone, [music] who turned the tide of the Battle of the Bulge, who embodied everything great about American military spirit. And that’s why 80 years later, we still tell his story, still study his operations, still speak his name with respect and admiration.

Because legends never die. They inspire new generations. They remind us what human beings can accomplish when they refuse to accept limitations. They show us that impossible is just a word, not a fact. General George Smith Patton proved that at Beson four words, 72 hours, 10,000 lives saved, one military miracle. And that’s why they called him Old Blood and Guts.

If this story of Old Blood and Guts greatest triumph moved you, hit subscribe. We’re bringing you more untold moments from General George Smith Patton, history’s greatest combat commander. Drop a comment about what makes Patton legendary and share this with anyone who needs to hear about true military genius. Thanks for watching and remember, when everyone else saw impossible, old blood and guts saw opportunity. That’s leadership.

That’s courage. That’s the spirit that changed

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load