June 24th, 1944, Oakidge, Tennessee. General Leslie Groves just approved construction of a uranium enrichment plant that his own advisers said would take 6 months to build. He gave the contractors four. Actually, scratch that. He wanted the first production unit running in just 75 days. Here’s the contradiction that should be impossible.

The Philadelphia pilot plant had exploded just weeks before, killing two men and injuring 11 others. The technology was still untested at scale. And yet, Groves was betting everything on a process that his Manhattan Project colleagues had rejected 2 years earlier as technically unfeasible. But this wasn’t recklessness. This was desperation meeting innovation.

Because by mid 1944, the atomic bomb project was failing. The massive Y12 electromagnetic plant couldn’t produce enough enriched uranium. The enormous K25 gaseous diffusion plant was months behind schedule. And somewhere in the Pacific, American soldiers were dying by the thousands as they island hopped toward Japan.

The solution came from an unlikely source, the United States Navy. While the Army’s Manhattan project was pursuing billiondoll enrichment technologies, a Navy physicist named Philip Abson had been quietly perfecting a different approach. A method so simple it seemed almost primitive. Steam pipes and temperature differences. That’s it.

Today, you’re going to discover how Navy scientists and a Cleveland construction company pulled off one of the most remarkable engineering achievements of World War II. How they built 2,142 vertical columns, each 48 ft tall, arranged them in 21 massive racks, and used nothing but steam, cold water, and physics to help end the war.

This is the story of S50, the thermal diffusion plant that almost nobody remembers, but that accelerated the production of the Hiroshima bomb by approximately 1 week. To understand why S50 mattered, you need to understand the uranium crisis of 1944. Natural uranium contains only 71% of uranium 235, the isotope that can sustain a nuclear chain reaction.

The remaining 99.28% is uranium 238, which is essentially useless for building atomic bombs. To create a weapon, you need to concentrate uranium 235 to at least 89% purity. The challenge, these two isotopes are chemically identical. You can’t separate them with chemical reactions. The only difference is three neutrons in the nucleus, creating a tiny mass difference of just 1.26%.

The Manhattan project pursued multiple enrichment methods simultaneously. At Oakidge, Tennessee, the Y12 electromagnetic plant used massive machines called Calotrons based on Ernest Lawrence’s cyclron design. These devices used powerful magnets to bend the path of uranium ions, separating the lighter uranium 235 from the heavier uranium 238.

The technology worked, but barely. Y12 was plagued with problems. Magnets overheated. Vacuum seals failed constantly. Production crawled along at a fraction of the expected rate. Meanwhile, construction had begun on K25, an enormous gaseous diffusion plant. This half-mile long facility would push gaseous uranium hexaflloride through thousands of porous barriers, gradually concentrating uranium 235.

But K25 was a nightmare of its own. The barriers kept clogging. Corrosion destroyed equipment. By spring 1944, it was clear K25 wouldn’t be operational for months, maybe even a year. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific director at Los Alamos, was watching these failures with growing alarm. The laboratory had the bomb design ready.

They had the detonation mechanism perfected. What they didn’t have was enough enriched uranium. Without it, the entire Manhattan project would fail. $2 billion spent, three years of work, thousands of scientists, all for nothing. That’s when Oppenheimer remembered something.

Back in February 1944, he’d received reports about a Navy project in Philadelphia. A physicist named Philip Ablesen was running thermal diffusion experiments at the Philadelphia Navyyard. The process seemed crude compared to the sophisticated technologies the Manhattan project was developing, but it had one massive advantage. It actually worked.

Philip Abson was only 31 years old in 1944, but he was already a significant figure in nuclear physics. He’d been among the first American scientists to verify nuclear fision in 1939. The following year, he’d co-discovered Neptunium, the first transuranium element. When World War II began, he turned his attention to uranium enrichment.

Abson’s approach was based on a phenomenon discovered in the 19th century called thermal diffusion, specifically the set effect. Here’s how it works. When you have a mixture of molecules and you create a temperature difference across that mixture, the lighter molecules migrate toward the hot side while the heavier molecules move toward the cold side.

German scientists Klaus Clusius and Ghard Dickl had used this principle in 1938 to separate isotopes of neon gas. Abelson adapted this concept for liquid uranium hexaflloride. His design was elegantly simple. Two concentric vertical pipes. The inner pipe made of nickel to resist corrosion carried high pressure steam at 545° F. The outer pipe made of copper was cooled by water at 155°.

Between these pipes was a gap measuring between 0.21 and 0.38 mm, barely thicker than a sheet of paper. into this impossibly narrow space. Ablesson pumped liquid uranium hexaflloride under pressure. The temperature gradient did the rest. The lighter uranium 235 molecules concentrated near the hot inner wall. Convection currents carried this enriched material upward.

The heavier uranium 238 sank downward along the cold outer wall. Over time, slightly enriched uranium collected at the top of the column while depleted uranium pulled at the bottom. But slightly is the key word. A single column could only increase uranium 235 concentration from 71% to maybe 75%.

To reach weapons grade purity of 89%, you’d need thousands of columns operating in series, each one feeding into the next. The mathematics were daunting. Ablesson calculated that producing 1 kilogram per day of 90% enriched uranium would require 21,800 columns, each 36 ft tall. When Abson presented this proposal to the Manhattan Project’s S1 Executive Committee in January 1943, they rejected it immediately. The committee chairman, Edgar Murphrey, ran the numbers.

Such a plant would cost $32.6 million to build and require 600 days to reach equilibrium production. The operating costs would exceed $62,000 per day. They rounded up and declared the project would cost $75 million with no uranium production by 1946. The decision was final. Liquid thermal diffusion was dead. But Abson didn’t quit.

With Navy funding, he built a pilot plant at the Anacostia Naval Air Station in Washington, DC. Using columns 36 ft tall. The results were promising but limited. In September 1943, he moved the project to the Philadelphia Navy Yard where he had access to industrialcale steam systems. The Philadelphia plant expanded to 102 columns, each now 48 ft tall, arranged in a single rack. The Navy wasn’t interested in atomic bombs.

They wanted nuclearpowered submarines. Admiral Harold Bowen saw thermal diffusion as a way to produce fuel for nuclear reactors. Interservice rivalry also played a role. President Roosevelt had explicitly excluded the Navy from the Manhattan project in March 1942. The thermal diffusion program became the Navy’s way to maintain a stake in atomic energy research.

But here’s what they didn’t know. That Navy project in Philadelphia, the one the Army had dismissed as impractical, was about to become the Manhattan Project’s lifeline because Robert Oppenheimer had just realized something that would change everything. On March 4th, 1944, Oppenheimimer wrote to James Conan, chairman of the National Defense Research Committee.

He requested all available reports on thermal diffusion. When he studied Ablesson’s data, Oppenheimer saw what the S1 committee had missed. Yes, thermal diffusion couldn’t produce weaponsgrade uranium on its own, but that was never the point. The genius was in the system integration.

If you ran the enrichment processes in series rather than in parallel, everything changed. Start with thermal diffusion to boost natural uranium from 71% to about 89%. Feed that slightly enriched uranium into the gaseous diffusion plant at K25 which could concentrate it to 23%. Finally run it through the electromagnetic calatrons at Y12 to reach 89% purity. The mathematics were compelling.

An electromagnetic plant that could produce one gram of 40% enriched uranium per day from natural feed could produce two grams of 80% enriched uranium from feed already enriched to 1.4%. You’d more than double Y2’s output without building a single new calatron. Better yet, you could build a thermal diffusion plant quickly using simple construction techniques and readily available materials.

On April 28th, 1944, Oppenheimer wrote directly to General Groves with his proposal. The production of the Y12 plant could be increased by some 30 or 40% and its enhancement somewhat improved many months earlier than the scheduled date for K25 production. Groves immediately grasped the implications. He’d been under enormous pressure to deliver results.

The Manhattan project had consumed over $2 billion with no finished weapon to show for it. Military planners were preparing for Operation Downfall, the invasion of Japan, with casualty estimates exceeding 1 million American servicemen. Any method that could accelerate uranium production, even by a few weeks, could save thousands of lives.

On May 31st, 1944, Groves appointed a review committee consisting of Murphrey, Warren Lewis, and Richard Tolman to investigate Oppenheimer’s proposal. The committee visited the Philadelphia Navyyard the very next day. They watched Abson’s columns in operation. They examined the engineering specifications. They studied the production data.

Their report concluded that Oppenheimer was fundamentally correct, though his estimates were slightly optimistic. Adding two additional racks to the Philadelphia pilot plant would take 2 months, but wouldn’t produce sufficient feed for Y12’s requirements. The only solution was to build a fullscale production facility.

On June 12th, Groves asked Murphrey for a detailed cost estimate. The specifications called for 1,600 columns capable of producing 50 kg of uranium enriched to between.9 and 3.0% per day from natural feed. Murphy’s team calculated the cost at 3.5 million for a 1600 column plant. Groves approved construction on June 24th, 1944. Now came the impossible part.

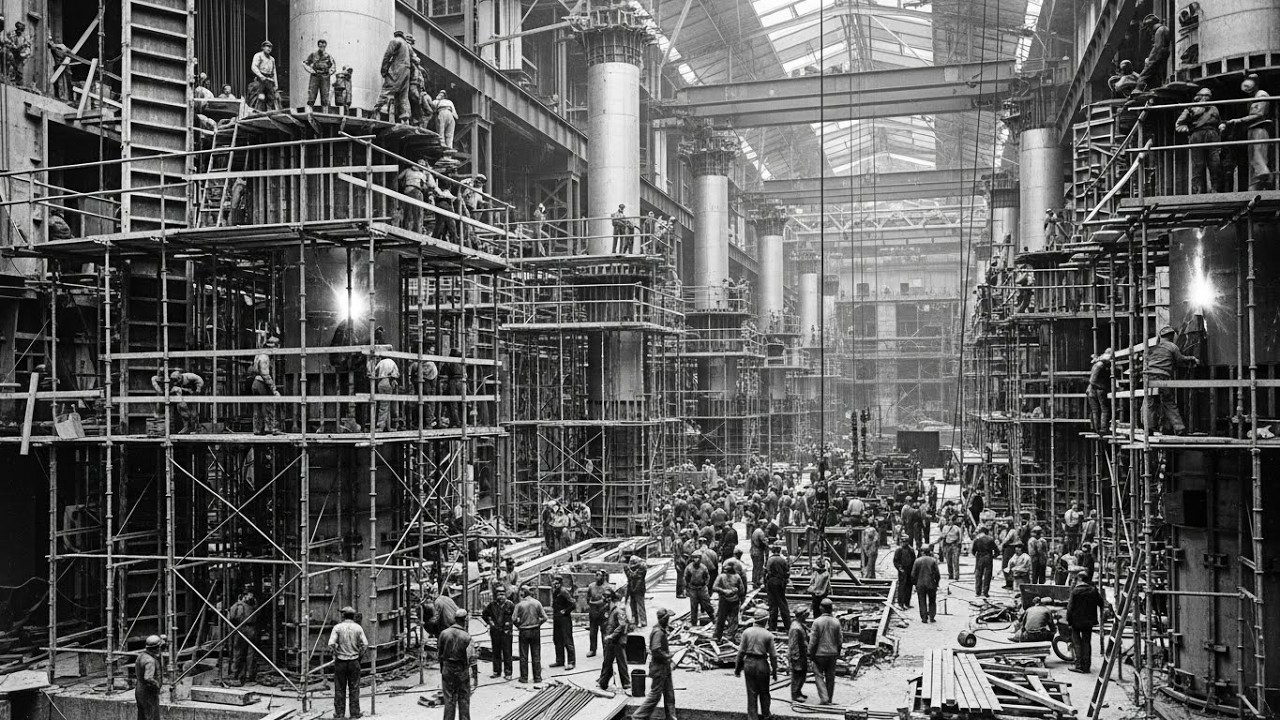

Groves informed the military policy committee that the plant would be operational by January 1st, 1945, less than 7 months away. But even that wasn’t fast enough. Privately, Groves demanded that HK Ferguson Company have the first production unit running in just 75 days, 4 months to build the entire facility. The scale of the challenge was staggering.

The production plant would consist of 21 racks, each containing 102 columns. That’s 2,142 columns total. Each column measured exactly 48 ft in height and 5 in in diameter. The inner tubes had to be manufactured from nickel to tolerances of plus or minus.003 in. The spacing between inner and outer tubes required precision of plus or minus 0.0002 in.

These tolerances were extraordinary for 1944 manufacturing capabilities. 23 companies were approached. Most declined immediately when they learned the specifications and timeline. Only two accepted. The Grenell company of Providence, Rhode Island, and the Maring and Hansen Company of Washington DC.

took on the challenge of manufacturing columns to specifications that seemed impossible to achieve. The site selected was at Oak Ridge, immediately adjacent to the K25 powerhouse. This location provided three critical advantages. Steam could be piped directly from the K25 boilers. Cooling water could be drawn from the nearby Clinch River at a rate of 15,000 gall per minute.

and security was already established for the classified Manhattan project facility. On July 9th, 1944, ground was broken at the S50 site. The S50 was a security code name. Construction employment peaked at 1,900 workers in September. The facility required massive infrastructure.

The main process building alone measured 522 ft long, 82 ft wide, and 75 ft high. It was painted black to reduce visibility from the air. Inside this structure, the 21 racks were arranged in three groups of seven. Each rack stood as a massive tower of 102 vertical columns. Running the length of the west side was a mezzanine with 11 control rooms, each for two racks.

Adjacent to each control room was a transfer room containing the dangerous equipment for loading uranium hexaflloride feed and removing enriched product. The real breakthrough came when engineers solved the problem nobody saw coming, and it involved a decision that would haunt them just weeks later in a Philadelphia transfer room.

On September 2nd, 1944, disaster struck the Philadelphia pilot plant. At 1:20 p.m., Private Arnold Craish of the Special Engineer Detachment was working in a transfer room with two civilian chemists, Peter Newport Bragg, Jr., and Douglas Paul Megs. They were attempting to replenish a 600 lb cylinder of uranium hexaflloride when it exploded without warning. The blast ruptured nearby steam pipes.

Superheated steam at 545° F mixed with vaporized uranium hexafflloride, creating hydrofluoric acid. This chemical is among the most dangerous industrial substances. It penetrates skin instantly, dissolving flesh and bone while destroying nerve endings. Private John Hoffman ran through the toxic cloud to rescue the three men. Bragg and Megs died from their injuries.

Krabish and nine others including four soldiers were badly burned but survived. Hoffman himself suffered burns, earning the Soldiers Medal, the Army’s highest honor for valor in a non-combat situation. It remains the only soldiers medal awarded to anyone in the Manhattan district. The accident investigation revealed a critical design flaw.

The cylinder was made of steel with a nickel lining instead of solid seamless nickel. Why? Because the army’s wartime procurement had preempted nickel production, forcing contractors to use composite construction. The steel couldn’t withstand the corrosion and pressure. It failed catastrophically. This explosion happened just 69 days after construction began at Oak Ridge.

1/3 of the S50 plant was already complete. The first rack had just commenced operations on September 16th. Groves had a decision to make. Shut down construction and redesign the system, losing months of time, or press forward with modifications. Groves chose to continue.

Colonel Stafford Warren, chief of the Manhattan district’s medical section, developed emergency treatment protocols for uranium hexaflloride exposure. All personnel received intensive safety training. The Naval Hospital created new procedures for handling hydrofluoric acid burns. And critically, Abson and 15 of his staff relocated from Philadelphia to Oakidge to train operators on site.

By January 1945, all 21 racks were installed and ready for operation. The construction contract terminated on February 15th with remaining electrical and insulation work assigned to local Oak Ridge contractors. The main plant became fully operational in March 1945, exactly 9 months after Oppenheimer’s initial proposal. But there was a problem.

The K25 powerhouse couldn’t supply enough steam. As stages of the gaseous diffusion plant came online, competition for steam became critical. The solution required building a dedicated boiler plant for S50. The Navy provided 12 surplus boilers originally manufactured for destroyer escorts. These operated at 450 lb per square in instead of the original,000 PSI specification.

The reduced steam pressure lowered the hot wall temperature, decreasing efficiency, but the trade-off was worthwhile because the destroyer escort boilers were oil fired and immediately available. A 6 milliongal oil tank farm was constructed with sufficient storage to operate S50 for 60 days independently. The new boiler plant was approved on February 16th, 1945. The first boiler started on July 5th.

Full operations commenced on July 13th, just 5 days before the successful Trinity test of the plutonium bomb in New Mexico. Operating S50 required unprecedented precision. The Fur Cleave Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary created by HK Ferguson specifically to operate the plant, employed 1,600 workers at Peak in April 1945.

The plant ran continuously 24 hours per day. Each rack consumed 11.6 megawatt of power. The enrichment process worked exactly as Abson predicted. In normal operation, one pound of product was drawn from each circuit in 285 minutes. With four circuits per rack, each rack produced 20 lb per day. Production initially struggled due to leaks and shutdowns. In October 1944, S50 produced just 10.

5 lbs of uranium enriched to 0.852%. But by June 1945, monthly production reached 12,730 lb. The integration with other enrichment plants created a cascade system. S50 enriched natural uranium from 0.71% to 0.89%. This material fed into K25’s gaseous diffusion process which boosted concentration to approximately 23%.

Finally, Y12’s electromagnetic calotrons refined it to 89% sufficient for weapons use. Total S50 production reached 56,54 lb of uranium hexaflloride. Historians estimate that S50’s contribution accelerated the completion of the Little Boy uranium bomb by approximately 1 week. That bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan on August 6th, 1945, containing 64 kg of enriched uranium.

less than 1 kilogram underwent fision, releasing energy equivalent to 15,000 tons of TNT and killing an estimated 70,000 to 80,000 people instantly. However, the biggest shock came after the war ended when Manhattan project leaders finally revealed what they really thought about the plant that helped end the war. On September 4th, 1945, less than a month after Hiroshima, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Peterson recommended shutting down S50 permanently. The order came through immediately.

By September 9th, all production had ceased. The columns were drained and cleaned. Furlev Corporation employees received two week termination notices. The shutdown was brutal and swift. Voluntary resignations had already reduced Flev’s payroll from 1,600 workers to about 900. Only 241 remained by the end of September. Furlev’s operating contract terminated on October 31st, 1945.

The last employees were laid off on February 16th, 1946. Responsibility for the S50 buildings transferred to the K25 office. Why the rapid abandonment, economics, and efficiency? S50 had been built as an emergency measure optimized for speed rather than operating costs. The plant consumed enormous amounts of steam and cooling water.

Its enrichment factor was low compared to gaseous diffusion. As K25 completed construction and resolved its technical problems, liquid thermal diffusion simply couldn’t compete. General Groves himself admitted the miscalculation. If I had appreciated the possibilities of thermal diffusion, he later wrote, we would have gone ahead with it much sooner, taken a bit more time on the design of the plant and made it much bigger and better.

Its effect on our production of uranium 235 in June and July 1945 would have been appreciable. That statement reveals the cruel irony of S50. It succeeded brilliantly at its mission while simultaneously proving itself obsolete. The plant accelerated uranium production at a critical moment, but only because it was built quickly rather than optimally.

A better designed facility would have been more efficient, but it would have taken longer to construct, negating its primary advantage. Starting in May 1946, the S50 buildings found a second life with the United States Army Air Force’s nuclear energy for the propulsion of aircraft project. Fairchild aircraft conducted burillium experiments there.

Workers fabricated blocks of enriched uranium and graphite for reactor research. NEPA operated until May 1951 when it was superseded by the Joint Atomic Energy Commission Air Force Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion Project. The S50 plant was disassembled in the late 1940s. Equipment was hauled to the K25 powerhouse area where it sat in storage before eventually being salvaged or buried.

The massive black process building was demolished. Today, nothing remains at the site except historical markers and contaminated soil requiring ongoing environmental monitoring. S50 remains the only production scale liquid thermal diffusion plant ever built. The technology was never used again for uranium enrichment. Modern enrichment relies almost exclusively on gas centrifuges, which are vastly more efficient than any method available during World War II.

A modern centrifuge cascade can enrich uranium to weaponsgrade purity using a fraction of the energy and space that S50 required. Yet the engineering achievement stands as remarkable. From concept to full operation in 9 months, 2,142 precision manufactured columns, each 48 ft tall, operating simultaneously within tolerances measured in thousandth of an inch.

A construction workforce of,900 building a classified facility under wartime conditions. An operating staff of 1600 managing one of the most dangerous industrial processes imaginable, handling thousands of kg of corrosive, toxic radioactive material. The lessons of S50 resonate far beyond uranium enrichment. This project exemplifies how innovation succeeds under constraints. Consider the decision-making process.

The Manhattan Project initially rejected thermal diffusion based on theoretical calculations showing it couldn’t produce weaponsgrade uranium. They were absolutely correct. But Oppenheimimer recognized that the wrong question was being asked. The question wasn’t, can thermal diffusion produce weaponsgrade uranium? The question was, can thermal diffusion improve the performance of our existing enrichment systems? By reframing the problem, an impossible challenge became a practical engineering solution. The timeline demonstrates what focused urgency can accomplish. When

Groves demanded a 75-day construction schedule, experienced engineers said it couldn’t be done. They were almost right. It took 69 days to get the first rack operational. Actually, 6 days faster than Groves demanded. The full plant took 9 months instead of the standard 18-month construction timeline for comparable industrial facilities.

That acceleration came from eliminating bureaucratic delays, prioritizing critical path items, and accepting calculated risks. The integration approach pioneered at S50 influenced modern industrial processes. The concept of cascading multiple different technologies in series, each optimized for a specific enrichment range, became standard practice.

Modern isotope separation facilities use similar staged approaches, combining technologies that individually would be inefficient but together create optimal results. Safety lessons were written in blood. The Philadelphia explosion killed two men and nearly derailed the project. But the response, developing immediate treatment protocols and comprehensive training programs, established standards that protected thousands of workers at Oakidge.

No fatal accidents occurred at the S50 production plant despite handling far larger quantities of dangerous materials. Perhaps most significantly, S50 represents the power of interervice cooperation, even when that cooperation emerges from rivalry. The Navy funded thermal diffusion research because they were excluded from the Army’s Manhattan project.

That rivalry inadvertently created a parallel research program that became critical when the Army’s methods faltered. Modern military operations now deliberately structure overlapping research programs, recognizing that redundancy and competition can produce unexpected breakthroughs. Today, uranium enrichment faces new challenges.

Nuclear power generation requires lowenriched uranium for civilian reactors. Arms control treaties require monitoring enrichment facilities to prevent weapons proliferation. Modern centrifuge technology has made enrichment faster and cheaper, but also more accessible to nations seeking nuclear weapons. The technical problem that S50 helped solve in 1944 remains politically contentious 80 decades later.

If you found this story fascinating, subscribe to the channel for more deep dives into wartime engineering problems and the technical solutions that changed history. Next week, we’re exploring how British engineers built the Malberry Harbors, the artificial ports that made the D-Day invasion possible. Two massive harbors constructed in sections, towed across the English Channel, and assembled under enemy fire.

The engineering challenge that Winston Churchill called one of the most difficult and daring undertakings of the war. Hit the notification bell so you don’t miss it. And if you want to explore more stories of innovation under pressure, check out our video on the Enigma codereing machines at Bletchley Park.

How Polish mathematicians and British engineers built electromechanical computers that could break German military codes in minutes, processing millions of possible combinations. The S50 plant lasted less than a year in operation. But in that brief window, it proved that sometimes the solution to an impossible problem isn’t to work harder at the same approach.

Sometimes you need to step back, reframe the question, and recognize that the inferior technology used correctly becomes the breakthrough that changes Everything.

News

Beyond the Stage and the Stadium: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Unveil Their Surprising New Joint Venture in Kansas City DT

KANSAS CITY, MO — In a world where celebrity business ventures usually revolve around obscure crypto currencies, overpriced skincare lines,…

Midnight Mercy Dash: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce’s Secret Flight to Dallas to Support Patrick Mahomes After Career-Altering Surgery DT

In the high-stakes world of professional sports and global entertainment, true loyalty is often tested when the stadium lights go…

From Heartbreak to Redemption: Travis Kelce Refuses to Retire on a “Nightmare” Season as He Plots One Last Super Bowl Run Before Rumored Wedding to Taylor Swift DT

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — The atmosphere inside Arrowhead Stadium this past Sunday was unrecognizable. For the first time since 2014,…

Through the Rain and Defeat: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Retreat to New York After Chiefs’ Heartbreaking Loss to Chargers

KANSAS CITY, Mo. – In the high-stakes world of the NFL, not every game ends in celebration. For the Kansas…

From Billion-Dollar Bonuses to Ringless Rumors: The Social Dissects Taylor Swift’s Generosity and the “Red Flags” in Political Marriages DT

In the ever-evolving landscape of pop culture and current affairs, the line between genuine altruism and calculated public relations is…

Tears, Terror, and a New Love: Inside the Raw and Heart-Wrenching Reality of Taylor Swift’s “The End of An Era” Premiere DT

For years, Taylor Swift has been the master of her own narrative, carefully curating the glimpses of her life that…

End of content

No more pages to load