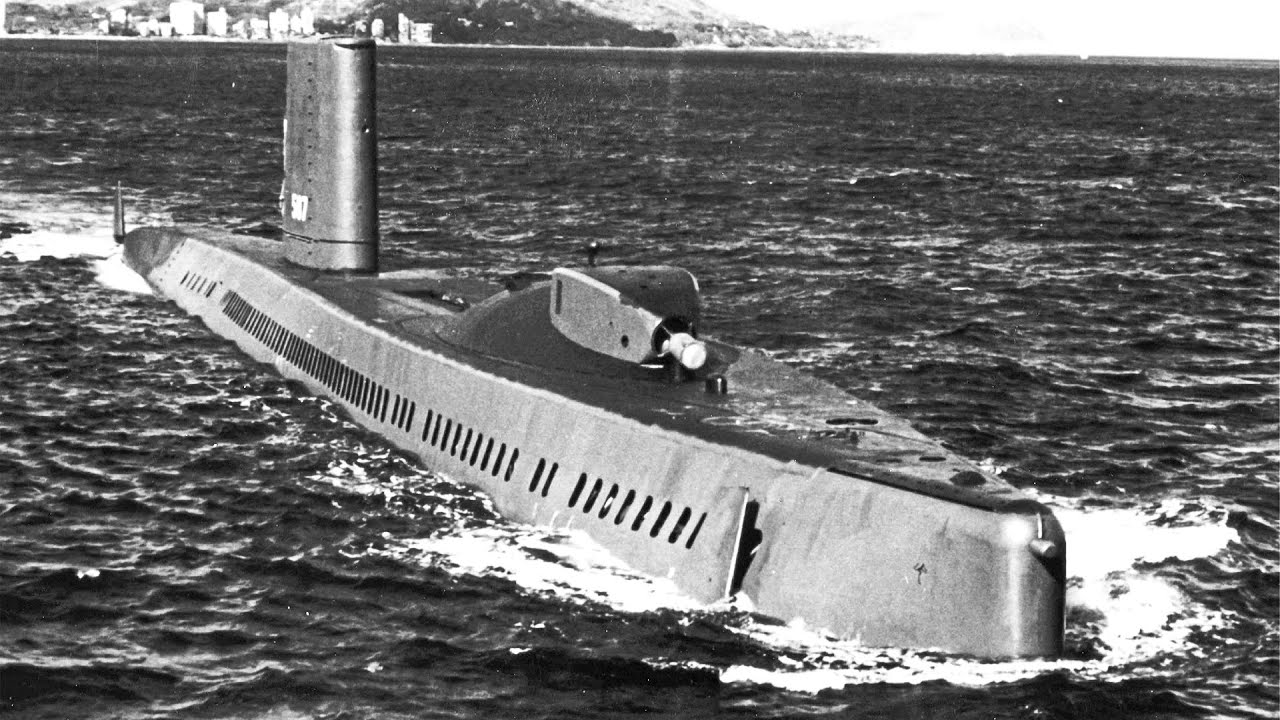

In March 1968, the Pacific Ocean stretched endless and cold beneath the slate gray sky. The Soviet ballistic missile submarine K129 cut silently through those waters, a shadow gliding beneath the waves. She was a Gulf 2class diesel electric submarine, one of the most secret and heavily armed vessels of the Soviet Pacific fleet.

Her orders were clear. patrol a preassigned sector northeast of Hawaii remain undetected and standby to deliver a nuclear strike if the unthinkable happened. On board were 98 men, sailors, engineers, officers, all sworn to secrecy, all trained to vanish beneath the ocean for months without trace. She departed the Ribbachi Naval Base on the Kamchatka Peninsula in late February.

Her hatches sealed, her crew waving quietly to families who would not see them again. The Cold War was at its height. Both the Soviet Union and the United States maintained fleets of submarines capable of launching nuclear missiles. Deterrence was built on fear. Fear of the other side’s silence. For several days, K129 maintained her scheduled radio check-ins.

Then, on the night of March 8th, 1968, the line went dead. No transmission, no coded message, nothing. Hours passed, then days. Commanders at the Soviet Pacific Fleet headquarters grew restless. They assumed a technical malfunction, then perhaps a communication error. When additional scheduled signals failed to arrive, anxiety turned to dread.

The Soviet Navy began a massive search. Dozens of ships left their ports, sweeping across hundreds of thousands of square miles of ocean. Aircraft flew roundthe-clock reconnaissance missions, dropping sonar boys into the sea. For nearly 2 months, the search continued, and yet not a trace of K 129 appeared. The sea had swallowed her whole.

Officially, the Soviet Union announced nothing. The loss of a strategic nuclear vessel could not be admitted publicly. Families of the crew were told little beyond that their loved ones had perished in a training accident. But in the corridors of Moscow’s naval command, the truth was unbearable. A ballistic missile submarine carrying three nuclear warheads and secret code books had disappeared somewhere in the Pacific.

Unbeknownst to them, the United States already knew something had happened. Across the ocean floor, hundreds of hydrophones belonging to the US Navy’s SOS network, the sound surveillance system, listened continuously for signs of submarine activity. On March 8th, the same night K129 vanished, sensors recorded a distant lowfrequency explosion.

It came from a remote sector of the North Pacific, thousands of miles from Soviet territory. The sound was faint but clear. Something had detonated deep beneath the surface. And that single anomaly would set in motion one of the most extraordinary intelligence operations in history. Within weeks, the US Navy began to analyze the acoustic data.

By comparing arrival times of the sound at multiple listening posts, analysts triangulated its source, a desolate patch of ocean nearly equidistant between Hawaii and the Kamchchatka Peninsula. The Navy’s next move was quiet and deliberate. They sent a submarine that had already been modified for espionage, USS Halibut. Originally built as a guided missile sub, Halibet had been refitted with specialized deep sea equipment, side looking sonar, highresolution cameras, and deployable underwater drones.

Her mission was to go where no other vessel could, and photograph the seafloor. Halibet sailed under the guise of routine exercises, but her true orders were classified. She crisscrossed to the area identified by Sosus, towing a long array of cameras along the seabed at depths approaching 16,000 ft. For weeks, the crew worked in shifts, maintaining silence as their ship traced slow grids across the ocean floor.

The images that returned were haunting. At first, only barren seabed and sediment clouds appeared. Then one day, the photos revealed twisted metal, scattered debris, and the unmistakable outline of a submarine’s hull. There it was, the K129. The vessel had broken into several sections. Her bow and missile compartment were largely intact, but her aft section had been obliterated.

The damage suggested an internal explosion, perhaps a torpedo detonation or missile malfunction. The find was extraordinary. The Soviets had searched for months without success, but the Americans now had precise coordinates of the wreck, and more importantly, the knowledge that it carried nuclear weapons and crypto systems in Washington.

The photographs were studied by intelligence chiefs. The implications were immense. If the US could somehow raise the submarine, even part of it, they could unlock Soviet naval codes, study missile guidance technology, and perhaps learn whether Moscow’s systems were vulnerable. But there was one problem. The wreck lay under three miles of water.

No ship, no crane, no machine on Earth had ever lifted anything from such depth. The idea was dismissed by many as impossible. But within the CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology, a handful of engineers refused to let the opportunity slip away. They proposed a plan that bordered on madness to build a ship capable of reaching the ocean floor, grasping the wreck, and bringing it to the surface.

The proposal reached the upper levels of the CIA in early 1970. It was approved in principle by President Nixon’s administration under the strictest secrecy imaginable. The project was cenamed Aorian. The first challenge was engineering. Lifting an object weighing thousands of tons from 16,000 ft would require a ship with unmatched stability.

An immense winch system, and a capture device that could survive pressure exceeding 7 tons per square in. The second challenge was concealment. The operation had to take place in international waters in plain view of Soviet surveillance satellites. The cover story needed to be convincing. The solution was ingenious.

The CIA reached out to billionaire industrialist Howard Hughes, whose companies already had contracts with the US government. Hughes’s reputation for eccentric ventures made him the perfect front. His corporation, Global Marine Development, would announce a project to mine the deep ocean for valuable mineral nodules, metallic lumps said to contain manganese copper and nickel.

The public would see a scientific experiment. In reality, it would be a front for a top secret salvage. A new ship would be built specifically for this task. It would carry a massive internal chamber, a moon pool, where the recovered submarine could be concealed from view. The mechanical claw that would grip the submarine was dubbed Clementine.

Its arms would extend from the end of a long steel pipe system lowered through the moonpool, capable of encasing the submarine and hauling it up as one piece. Every element of the operation would be conducted under civilian disguise. Engineers, ship builders, and technicians would believe they were working on a revolutionary mining platform.

Only a small circle within the CIA and Global Marine knew the truth. The project would cost over $300 million, an astronomical figure at the time, and would take years to complete. But the potential payoff, both strategic and psychological, was too great to ignore. Construction of the vessel began in 1972 at Sun Ship Building in Pennsylvania.

The Hughes Glowar Explorer, as it was publicly called, was unlike any ship ever built. Over 600 ft long, she could maintain her position over a single point on the ocean using dynamic thrusters guided by computer. Her moonpool, an enormous well open to the sea, allowed operations to occur completely out of sight. Inside it, engineers could hoist an object directly into the ship’s interior, close massive doors beneath, and hide the cargo from outside observers.

The media marveled at the project. Articles praised Hughes for pioneering ocean mining. No one suspected the real purpose. By the summer of 1974, the Glowar Explorer was ready. On June 20th, she departed Long Beach, California. Crewed by a mix of engineers, mariners, and CIA personnel posing as global marine contractors. Their destination, the coordinates of K129.

After two weeks at sea, the Glowar explorer arrived over the target site. The ocean around her was vast, empty, and silent. The crew anchored the vessel in place using her dynamic positioning system. Below them lay 16,500 ft of water and the shattered remains of a Soviet nuclear submarine. The descent began.

Section by section, the massive steel pipe string was assembled and lowered through the moonpool. Each segment was 40 ft long, locked to the next by hydraulic clamps. As the pipe extended downward, sensors tracked tension and pressure. At such depth, even the smallest miscalculation could destroy the system. It took days for the claw to reach the bottom.

When cameras finally illuminated the seabed, they saw the wreck, tilted, half buried in silt, but recognizable. Operators carefully maneuvered Clementine into place. Its six steel fingers opened wide, sliding beneath the hull of K129. Then slowly they closed. The capture was complete. Now came the hardest part, the lift.

As the ship’s giant winch engaged, the claw began its long ascent. The crew monitored every vibration through instruments. The load weighed thousands of tons. The stress on the pipe string was immense. At any moment, a single failure could send the entire assembly crashing back into the abyss. For days, the lift continued without incident. Hope grew that the impossible might succeed. Then disaster struck.

Halfway to the surface, tension readings spiked. Somewhere deep below, the claws began to give way. Engineers scrambled to compensate, but it was too late. With a sudden lurch, the structure failed. Twothirds of the submarine slipped free and plunged back into the darkness. Only the forward bow section remained caught in the damaged claw.

Inside the control room, the crew stared at the readings in silence. Years of planning, billions in today’s dollars, and the priceless intelligence they had sought, lost in seconds. But the mission was not over. They still had a portion of the submarine. The decision was made to continue the lift. Slowly, painfully, the remaining section rose toward the surface.

When the first pieces of corroded steel broke through the water into the moonpool, there was no cheer, only quiet disbelief. They had done what no one in history had achieved. Raised part of a sunken nuclear submarine from three miles down. Inside the recovered section, investigators made a grim discovery.

Six bodies of Soviet sailors lay preserved by the freezing depths. They had been trapped when the submarine imploded. The crew of the Glomar Explorer held a solemn ceremony. The bodies were placed in a steel casket, draped in the Soviet flag, and given military honors before being lowered back into the sea. For decades, that ceremony remained classified.

When the footage was finally shown to Russia in 1992, it was received with respect, a rare human gesture amid cold war secrecy. As for the rest of the recovery, the details remain classified. Intelligence reports suggest that the Americans retrieved parts of the fire control system, two nuclear torpedoes, and possibly sections of the submarine’s code equipment.

It was not the victory they had envisioned, but it was still extraordinary. The CIA now possessed physical pieces of a Soviet strategic weapon, proof of concept that such missions could be done. The Glowar Explorer returned quietly to port. The operation was considered among the most sensitive in US intelligence history. Everyone involved signed strict confidentiality agreements.

For a while, the secret held. Then, in early 1975, the story broke. A journalist investigating Howard Hughes’s mysterious ship uncovered hints of a CIA operation. On March 18th, the New York Times published the first public account of Project Aorian. The CIA faced an immediate dilemma. To confirm or deny the story would reveal classified information, but silence would only fuel speculation.

Their official statement became a phrase that entered history. We can neither confirm nor deny the existence of the information requested. It became known as the Glomar response, a model for government secrecy still used today. Though the mission recovered only part of K129, it reshaped undersea operations forever. The engineering breakthroughs developed for Aorian paved the way for deep sea drilling, cable repair, and future covert projects.

The Glomar Explorer itself served later in civilian roles before being decommissioned. For the Soviets, the loss of K129 remained a wound. They never learned how much of the submarine had been taken or what the Americans had discovered. For the United States, Project Aorian was a triumph of science and secrecy, proof that there was no frontier too deep, no mission too impossible.

To this day, the full truth remains locked away. The cause of K129 sinking is still debated. a missile malfunction, a torpedo detonation, perhaps even a collision with an American sub. Whatever happened that night in March 1968, 98 men went to their deaths, serving a system that kept them nameless for decades.

Their submarine became a porn in a larger game, a symbol of the shadow war that unfolded beneath the oceans while the world above remained unaware. Project Aorian was not merely an engineering feat. It was a statement that in the Cold War no place was beyond reach. Somewhere on the Pacific seabed, the missing sections of K 129 still lie undisturbed.

Time has claimed her, but her story endures. A silent monument to secrecy, ambition, and the perilous balance of power that once defined the world. In March 1968, a Soviet submarine disappeared beneath the Pacific. Years later, an American ship reached down into the dark to bring it back. Between those two moments lies a story of science, secrecy, and silent rivalry.

A chapter of history hidden beneath the waves. Though the sea closed over her once more, the legacy of K129 and Project Aorian lives on. A reminder that even in the coldest depths, the pursuit of knowledge and dominance never sleeps.

News

Iraqi Republican Guard Was Annihilated in 23 Minutes by the M1 Abrams’ Night Vision DT

February 26th, 1991, 400 p.m. local time. The Iraqi desert. The weather is not just bad. It is apocalyptic. A…

Inside Curtiss-Wright: How 180,000 Workers Built 142,000 Engines — Powered Every P-40 vs Japan DT

At 0612 a.m. on December 8th, 1941, William Mure stood in the center of Curtis Wright’s main production floor in…

The Weapon Japan Didn’t See Coming–America’s Floating Machine Shops Revived Carriers in Record Time DT

October 15th, 1944. A Japanese submarine commander raises his periscope through the crystal waters of Uli at what he sees…

The Kingdom at a Crossroads: Travis Kelce’s Emotional Exit Sparks Retirement Fears After Mahomes Injury Disaster DT

The atmosphere inside the Kansas City Chiefs’ locker room on the evening of December 14th wasn’t just quiet; it was…

Love Against All Odds: How Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Are Prioritizing Their Relationship After a Record-Breaking and Exhausting Year DT

In the whirlwind world of global superstardom and professional athletics, few stories have captivated the public imagination quite like the…

Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Swap the Spotlight for the Shop: Inside Their Surprising New Joint Business Venture in Kansas City DT

In the world of celebrity power couples, we often expect to see them on red carpets, at high-end restaurants, or…

End of content

No more pages to load