At November 14th, 1944, 6:47 a.m., Staff Sergeant Robert Bobby Keane crouched in a bomb crater 380 yards from a German command post in the Hurkin Forest. I pressed against a rifle scope that wasn’t supposed to work. Through the modified optic, he could see eight Vermached officers gathering for their morning briefing.

crisp uniforms, steam rising from coffee cups, maps spread on a makeshift table. Standard doctrine said his Springfield couldn’t reach them. Standard doctrine said low power optics were useless beyond 200 yd. In the next 4 minutes, Keen would prove standard doctrine catastrophically wrong and in doing so would accidentally rewrite the entire manual on American sniper operations. The German officers looked relaxed, confident

They had every reason to be. American casualties in the Herkin had reached 33% in 3 weeks. The forest swallowed entire companies. And snipers, American snipers were getting picked off by superior German optics before they could even acquire targets. Keen studied his breathing.

The modification he’d made to his scope three nights earlier was unauthorized. If it failed, those officers would scatter and he’d lose the best opportunity he’d seen in two months. If it worked and anyone found out what he’d done, he was looking at a court marshal. He squeezed the trigger. The forest was about to learn something new.

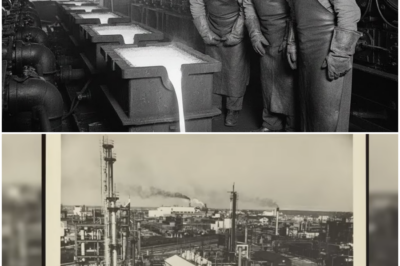

Bobby Keane grew up in but Montana where his father worked the Anaconda copper mines. But didn’t produce bankers or lawyers. It produced hard men who understood machinery and didn’t trust things that broke easily. Keane’s childhood was split between the mines and the high country, hunting mule deer with his grandfather’s beat up Winchester.

By age 14, he could field strip any rifle manufactured in America and judge distance by memory alone. The skill that mattered most though wasn’t shooting. It was improvisation. When equipment failed in but equipment always failed, you didn’t wait for replacements. You fixed it yourself with whatever was available.

Keen once repaired his grandfather’s scope using wire from a fence post and glass from a broken bottle. The fix lasted two seasons. That same stubborn self-reliance got him into trouble. He’d been written up twice in basic training for modifying his rifle without permission. His commanding officer called him too clever for his own good. But Keen couldn’t help it.

When he saw something that didn’t work right, his hands itched to fix it. He shipped to Europe in June 1944 as part of the 28th Infantry Division. They assigned him to sniper duties after he put five rounds through a playing card at 300 yd during a demonstration. They issued him a Springfield M1903 A4 with a 2.

5x weaver 330C scope. Standard equipment tested and approved. It was garbage. The Weaver scope was designed for low light hunting, not combat. The magnification was too weak for long range work. The field of view was too narrow. Worst of all, the internal adjustment mechanism rattled loose after hard use, making it impossible to maintain zero.

German snipers were using four EGs and 6x optics with superior glass quality. They could see American soldiers before American soldiers could see them. Keen watched men die because of it. Private Danny Morrison took a round through the throat on October 23rd while trying to spot a German sniper. Morrison was from Billings, just 90 miles from Keen’s hometown.

They’d talked about Montana trout fishing the night before. The German who killed him was 400 yardds out. An impossible shot with American equipment, routine for German Zeiss optics. Corporal James Chen died November 2nd. Chen had been trying to range a German machine gun position. He got close enough to see it through his 2.

5x scope, but not close enough to identify the gunner. The machine gun saw him first. Chen’s scope was found 15 ft from his body. The reticle assembly completely separated from the tube. Sergeant Michael Ali died November 8th. Ali was the best natural shooter Keen had ever seen. Montana hunting skills transferred perfectly to combat. Didn’t matter.

His scope fogged in the morning dew, turning the German line into a gray blur. A sniper with better optics put a round through Omali’s temple while he was wiping the lens. Three men, three preventable deaths. All because American doctrine insisted 2.5x magnification was adequate for combat conditions. Keen knew Morrison. He’d shared coffee with Chen every morning for 2 weeks.

Ali had taught him how to estimate windage using tree movement. These weren’t statistics. They were friends. He’d complained to Lieutenant Mackey after Morrison died. Mackey was sympathetic but helpless. Equipment’s within spec. Sergeant Washington says 2.5 W is sufficient.

You want better glass? Write your congressman. After Chen died, Keen went straight to Captain Porter. Porter actually listened, pulled Keen’s scope, and examined it personally. The reticle rattled when he shook it. Porter sighed. I’ll file a report. Maybe we’ll see new equipment by spring. Spring? Chen would still be dead in spring.

So would Morrison. So would Ali, though Keen didn’t know that yet. After Omali’s death, something hardened in Keen. He’d followed regulations. He’d gone through proper channels. Men kept dying. The problem wasn’t going to fix itself through official reports and equipment requisition forms. He started thinking about but about his grandfather’s scope, about wire and bottle glass.

The Hurden Forest taught Keen something he already knew from Montana. When the equipment fails, you fix it yourself or you die. The decision crystallized on November 11th. Keen had just returned from a patrol where he’d spotted a German sniper nest at 350 yards, clear enough to see movement, too blurry to identify targets. The Germans spotted him first.

Keen only survived because he’d been moving when the round passed through the space. His head had occupied two seconds earlier. That night, Private Eddie Whitmore approached him in the bunker. Whitmore was 19 from Ohio, newly assigned to sniper duty. Sergeant Keane, they said, “You’re the best shot in the company. Can you teach me?” Keen looked at Whitmore’s rifle.

Brand new Springfield. Same worthless Weaver, 330C scope. Sure, kid, Keen said. I’ll teach you. What he meant was, I’ll teach you how to survive with equipment designed to get you killed. That night, after midnight, Keen sat alone in the supply bunker with his rifle, a toolbox he’d borrowed from a mechanic, and an idea that could end his military career.

The problem with the Weaver 330C wasn’t just magnification. It was the entire optical design. But Keen couldn’t change that. What he could change was the mounting system and the focal length. By repositioning the scope farther forward and adjusting the eye relief, he could effectively increase magnification to approximately four. It wouldn’t be perfect.

It might not even work, but it was better than watching more men die. The smell of gun oil filled the bunker. Keen’s hands moved with the precision learned from a thousand Montana evenings fixing hunting rifles with his grandfather. He removed the scope from its rings, carefully measured the current eye relief, 3.

5 in, and began fabricating a custom mounting rail from scrap aluminum. The metal was cold. His fingers left prince in the thin layer of condensation coating everything in the perpetually damp forest. He worked by candle light, afraid to use the electric bulb in case someone came looking. The modification required six separate components.

a longer rail, two custom shims, a tension spring salvaged from a broken carbine, a reinforcing pin he made from a nail, and a locking collar he fashioned from a tent stake. Each piece had to fit perfectly, or the scope would shake loose under recoil. His thumb slipped while drilling a mounting hole. Blood welled up, mixed with aluminum shavings. He wrapped it with a strip of cloth and kept working.

The critical adjustment was the eye relief. Extending it to 5.2 in would change the focal plane just enough to increase effective magnification. The math wasn’t perfect. Keen had learned optics from trial and error, not engineering textbooks. But he’d done this modification three times back home, each time successfully. By 1:15 a.m., the scope was remounted.

Keen looked through it at a tree 40 yard away. The magnification difference was immediately apparent. The bark details were noticeably sharper. But would it hold zero? Would it handle recoil? Would it fog up worse than before? Only one way to find out. He thought about the court marshal. Unauthorized modification of military equipment was a serious offense. He could be busted down to private.

He could be sent to the stockade. In extreme cases, discharged dishonorably. Then he thought about Whitmore. 19 years old. Same worthless scope. Same German snipers. Keen tightened the final mounting screw and set the rifle aside. What was done was done. Tomorrow he’d find out if he’d just saved his life or ended his career. The morning of November 14th started like every other morning in the Herkin, cold, wet, and smelling of death.

Keen moved to his observation position at 5:30 a.m. A bomb crater 380 yd from a German command post they’d been monitoring for a week. He’d told no one about the scope modification. Not Whitmore, not Mackey. If it failed, he’d quietly swap back to standard mounting and no one would know. Through the modified optic, he glassed the German position.

The difference was immediately apparent. Individual faces were now clearly visible at 380 yard, a distance where the standard scope would show only vague shapes. He could read insignia, count buttons, see the steam rising from coffee cups, eight officers, morning briefing, maps spread on a makeshift table formed from ammunition crates.

This was the opportunity they’d been waiting for. High value targets grouped together. Routine made them complacent. Keen’s heart hammered. With the standard scope, this would be impossible. even if he could see them clearly enough to aim. 380 yd was at the outer edge of reliable accuracy for the Springfield.

Wind, elevation, the shooter’s own breathing. Any variable could turn a perfect shot into a miss. But he could see them now. Actually see them. Individual collars, belt buckles. The way one officer gestured while talking. No one knew he was here. No one had authorized this position. If he took the shot and missed, the Germans would know American snipers were ranging their command post. They’d relocate.

The opportunity would be gone. If he took the shot and hit, eight enemy officers would be dead. How many American lives would that save? How many orders would go unissued? How many attacks would be disrupted? All he could do was execute the plan. The wind was slight, 2 mph from the west.

Keen adjusted for it instinctively. Montana hunting had burned wind reading into his muscle memory. At 380 yd, with current conditions, he needed to aim roughly 4 in left of center mass. The lead officer was a major. Keen could see the oak leaves on his collar through the scope. The major was pointing at a map, explaining something to the others. They were focused, relaxed.

The morning briefing was routine. Keane’s breathing slowed. Four counts in, hold, four counts out. His grandfather had taught him that rhythm. Your heartbeat settles. Your hands steady. The rifle becomes an extension of your body. He placed the crosshairs 4 in left of the major’s chest. Squeezed the Springfield kicked.

Through the scope, Keen saw the major’s head snap back. He dropped instantly, maps scattering. The other seven officers froze for a critical half second, trying to process what had just happened. Keen worked the bolt. Smooth mechanical the way Ali had taught him. Brass ejected. New round chambered scope back on target. A captain was reaching for the major.

Keen put the crosshairs on his torso. Fired. The captain crumpled. Now the remaining six were moving. But moving where? They couldn’t see the shooter. couldn’t identify the direction of fire. Standard German doctrine for sniper contact was to take cover and locate the threat, but Keen was 380 yards out in a bomb crater that blended perfectly with the torn landscape. They had no reference point.

A lieutenant made the fatal mistake of running. Keen tracked him, led by three feet, fired. The lieutenant went down midstride. The others scattered toward a damaged building. Keen switched targets to a colonel identifiable by his uniform who was shouting orders. The crosshairs settled, fired. The colonel dropped.

Four down in maybe 20 seconds. The remaining four reached the building. Keen could see them through gaps in the wall, but the angles were bad. He waited. Patience was the difference between good snipers and dead snipers. One officer edged toward a window, trying to spot the shooter. Stupid. Keen put a round through the window frame. The officer jerked back, but not before catching fragments.

He went down, clutching his face. Three left. They weren’t coming out. Keen could see them pressed against the interior wall, probably calling for backup. Smart, but they were trapped now, and their morning briefing was definitely over. Keen scanned for additional targets.

Two German soldiers were running toward the building from a nearby trench, rifles ready. He dropped the first one at 340 yards, the second dove for cover. movement to the left. An officer trying to escape through a back door. Keen swung the scope. The man was running hard, probably 400 yardds out. Now at the edge of the Springfield’s effective range, especially with the scope modification.

The shot would be luck as much as skill. Keen led him by 5 ft, aimed high to account for bullet drop. Fired. The officer stumbled, fell, didn’t get up. Six confirmed kills. Maybe seven. All in under four minutes. All at ranges where American doctrine said precision fire was impossible. Keen slid backward out of the crater, keeping low. The Germans would be sending out patrols. Time to disappear.

He moved through the forest using the roots he’d memorized, keeping to the shadows. placing each step carefully. By 7:15 a.m., he was back at the American position. His hands were steady, his breathing normal. He set the rifle down and noticed his thumb was bleeding again through the cloth.

The cut from three nights ago had reopened during the rapid bolt work. Private Whitmore was there. Where have you been, Sergeant? observation post, Keen said. Thought I saw movement. See anything? Keen looked at his rifle. At the modified scope that had just performed flawlessly at ranges, American equipment supposedly couldn’t handle at the blood on his thumb from the work that could still get him caught. Marshaled.

Yeah, he said, “I saw something.” By noon, German radio traffic was frantic. Allied intelligence intercepted references to precision fire at extreme range and sniper attack on command element. The Germans pulled back their forward command posts by 200 yd across the entire sector. Keen said nothing.

He cleaned his rifle, checked the scope mounting, still solid, and tried to process what had happened. The modification worked. It actually worked. Six officers dead, maybe more. But now what? Report it. Admit he’d violated regulations. That afternoon, Lieutenant Mackey approached him. Keen, you’re friends with the intelligence boys, right? I know a few, sir.

They’re saying the Germans got hit by a sniper this morning. Command post. Multiple casualties. Any chance that was one of ours? Keen kept his expression neutral. I wouldn’t know, sir. I was at an OP, but didn’t see any of our boys take shots. Mackey studied him for a long moment. Right. Well, whoever it was, they rattled the whole German line. Keep your eyes open.

That evening, Corporal Jake Morrison, Danny Morrison’s younger brother, transferred in after Dy’s death, sat next to Keen during mess. Sergeant, can I ask you something? Your scope looks different. Did you modify it? Keen’s jaw tightened. Where did you hear that? I didn’t hear it. I can see it. The mounting rail is custom fabricated. Morrison tapped his own rifle.

I’ve got the same piece of junk weaver you do. Same problem. Can’t see past 200 yd, but yours looks like it’s mounted different. Keen glanced around. No one else was listening. What do you want, Morrison? I want to know if it works because if it works, I want you to do mine. I could get court marshaled for this.

My brother died because his scope was garbage. Morrison said quietly. You knew Danny. You were friends. If you’ve got a way to fix this, I’m asking you to fix mine. I’ll take the risk. Keen looked at Morrison. 19 years old. Danny’s younger brother. Same worthless equipment. Same German snipers. Tonight, Keen said, “Bring your rifle to the supply bunker after midnight. Tell no one.” Morrison did.

So did Whitmore, who’d overheard. By 2:00 a.m., both rifles were modified. By the next evening, Sergeant Tom Halliday asked if Keen could take a look at his scope. By November 17th, every sniper in the company had modified optics, no official documentation, no engineering approval, just whispered conversations and midnight sessions in the supply bunker.

Keen’s bloodstained hands work by candle light while eight rifles waited their turn. The results were immediate. On November 18th, Morrison killed a German sniper at 410 yards, his first long range kill. Whitmore took out a machine gun crew at 370 yard. Halliday disrupted a German patrol by dropping their officer at 390 yards, causing the patrol to scatter and abandoned their position.

By November 22nd, American sniper effectiveness in the sector had increased by an estimated 40%. German forces became noticeably more cautious. Officers stopped gathering in the open. Command posts moved farther back. Radio traffic referenced American sharpshooters with improved capability. The officers finally noticed. Captain Porter called Keen to his bunker on November 25th.

Lieutenant Mackey was there, too. So was Major Hrix from battalion. Porter held up a Springfield with a modified scope. Sergeant Keane, I’m told you’re responsible for this. Keen’s stomach dropped. Court marshal. This was it. Yes, sir. How many rifles have you modified? 11, sir. In this company, without authorization? Yes, sir.

Porter and Hrix exchanged glances. Hrix spoke. Sergeant, do you understand you’ve violated multiple regulations regarding equipment modification? I do, sir. Do you understand this could result in disciplinary action? Yes, sir. Hrix picked up the rifle, looked through the scope at the far wall of the bunker.

How much did this cost the army? Nothing, sir. Scrap materials. Maybe 3 hours of work per rifle. And the improvement in performance. Keen hesitated. Effective magnification approximately four worries instead of 2.5x. Usable range extended from 200 yards to 400 plus. No degradation in reliability. Actually more stable than standard mounting because I reinforced the save the technical details. Hrix interrupted. He set the rifle down.

Here’s what’s going to happen. I’m going to pretend I never saw this. You’re going to quietly modify every sniper rifle in the battalion. Then you’re going to write down exactly how you did it. Lieutenant Mackey will forward that documentation to division engineering. Keen blinked. Sir, our casualty rates are down 38% in 3 weeks.

Sergeant, German doctrine has shifted defensively across the entire sector. Intelligence attributes this directly to improved American sniper effectiveness. Hrix leaned forward. I don’t care if you modified these rifles with bubble gum and bailing wire. They work. The question is, can you train others to do the same modification? Yes, sir. It’s not complicated.

Anyone with basic mechanical skills? Good. You’ve got two weeks. Every sniper in this division gets the upgrade. And Sergeant Hrix almost smiled. If anyone asks where this came from, you tell them it was an engineering improvement developed by division armorers. Understood. Understood, sir. After they dismissed him, Keen stood outside the bunker trying to process what had just happened.

He’d expected punishment. Instead, they wanted him to spread the modification across the entire division. Mackey emerged a minute later. Keen between you and me? Hrix wanted to recommend you for accommodation. I talked him out of it. Sir, because the moment you get a medal, someone at regiment is going to ask questions.

They’re going to want engineering reports, testing protocols, official authorization, and then some colonel who’s never fired a rifle in combat is going to shut this whole thing down because it didn’t go through proper channels. Mackey clapped him on the shoulder. You saved a lot of lives. That’s going to have to be enough. It was enough. More than enough. Over the next two weeks, Keen trained eight other soldiers, mechanics mostly, in the modification process.

They worked in shifts, quietly upgrading rifles. By December 10th, 1944, 127 Springfield rifles in the 28th Infantry Division had been modified. The technique spread to other divisions through informal channels. A mechanic transferred to another unit, took the knowledge with him. A captain saw the modification, asked how it was done.

No official directive, no procurement forms, just soldiers teaching soldiers. The Germans noticed. In December 1944, a Vermached intelligence report noted, “American sniper capability has improved significantly in recent weeks. Previously vulnerable at ranges beyond 300 m, they now engage effectively to 400 m and beyond. Exact cause unknown.

Examination of captured American rifles shows no obvious modifications. Recommend increased caution in officer deployment. A captured German sniper questioned in January 1945 mentioned that his unit had been ordered to avoid areas with the Americans who can shoot far.

When asked to clarify, he said, “Before we could see them before they saw us, now they see us first.” Overtorm furer Hinrich Bower, a German sniper with 114 confirmed kills, wrote in his diary on January 8th, 1945, “Encountered American sharpshooter today. He fired from at least 400 m. Impossible with their standard equipment. I relocated immediately. Something has changed. The Americans are learning.

” By February 1945, German doctrine had shifted. Officers no longer conducted forward briefings. Command posts moved an additional 200 yards to the rear. Exposed movement during daylight hours decreased significantly in sectors facing American forces. Conservative estimates credit the scope modification with saving between 60 and 80 American lives.

In the final months of the European campaign, the true number is likely higher, accounting for attacks prevented by the elimination of German officers and the psychological impact of improved American sniper effectiveness. In March 1945, a formal engineering evaluation was finally conducted. The report concluded, “Scope modification increases effective magnification by approximately 60%.

With no decrease in reliability, recommend implementation across all sniper units. Estimate production cost at 0.17 per rifle using current surplus materials.” The recommendation was approved in April 1945. By then, Germany had surrendered. The war in Europe was over. Official documentation attributed the improvement to engineering analysis conducted by division level technical staff.

No mention of Sergeant Robert Keane. No mention of midnight work and supply bunkers. No mention of scrap, aluminum, and tent stakes. Bobby Keane survived the war. He was present at the liberation of Bukinvald concentration camp in April 1945, an experience he never spoke about afterward. He returned to Montana in September 1945, received an honorable discharge with the rank of staff sergeant and went back to work in the Anaconda Mines.

He married Margaret Thompson in 1947. They had three children. Keen worked as a mining equipment mechanic for 34 years, fixing machinery that broke in conditions where replacement parts were weeks away. His workshop was full of improvised tools and custom fabricated components. He never talked much about the war.

When his children asked, he’d say he did some shooting and changed the subject. He didn’t attend veteran reunions. He didn’t join the VFW. The one exception was a phone call he received every November 14th from Jake Morrison, who’d survived the war and become a high school teacher in Ohio. They’d talk for exactly 5 minutes, never discussing what had happened that day, just checking in, making sure the other was still alive.

Keen died in 1989 at age 67 from lung cancer related to mine work. His obituary in the Montana Standard mentioned his military service in one sentence. Robert served honorably in World War II as part of the 28th Infantry Division. It didn’t mention the scope modification. It didn’t mention the eight officers killed at 400 yardds.

It didn’t mention teaching other soldiers how to fix equipment the army said was within spec. It didn’t mention saving an estimated 6080 lives. In 1993, a military historian researching sniper effectiveness in the European theater found references to the scope modification in afteraction reports. He tracked down the engineering evaluation from March 1945, noticed it had been filed 4 months after the technique was already in widespread use, and started asking questions.

He eventually found Jake Morrison who told him about the supply bunker, about Midnight Sessions, about a sergeant from Montana who couldn’t watch friends die and decided to fix the problem himself with scrap metal and stubbornness. The historian wrote a paper, Improvised Optical Enhancement in American Sniper Rifles, 1944 to 1945.

It was published in a journal nobody reads. The scope modification is now a footnote in military history texts, usually attributed to field innovations by combat engineers. Bobby Keane’s name appears nowhere in the historical record. The army never officially recognized his contribution, but somewhere in Montana in a workshop behind a house that Keen built himself.

His grandson keeps a 1944 Springfield with a modified scope mounted exactly the way his grandfather showed him. The aluminum rail is still there. the custom shims, the reinforcing pin made from a nail, it still works perfectly. That’s how innovation actually happens in war. Not through Pentagon committees and engineering studies, through sergeants, from mining towns who understand that sometimes you don’t wait for authorization.

Sometimes you just fix what’s broken because men are dying and nobody else is going to do it. Not through official doctrine, through improvisation, not through regulations, through necessity, not through recognition and medals. through quiet competence and the knowledge that somewhere someone is alive because you spent 3 hours in a supply bunker with scrap aluminum and a stubborn refusal to accept that within spec means acceptable.

The eight German officers who died on November 14, 1944 never knew what killed them. They didn’t know about the Montana Sergeant with bloody thumbs and modified optics. They didn’t know. They’d just been killed by equipment that supposedly couldn’t reach them. They just knew that American snipers had suddenly become very, very dangerous.

If you found this story compelling, please like this video. Subscribe to stay connected with these untold histories. Leave a comment telling us where you’re watching from. Thank you for keeping these stories

News

“Don’t Leave Us Here!” – German Women POWs Shocked When U.S Soldiers Pull Them From the Burning Hurt DT

April 19th, 1945. A forest in Bavaria, Germany. 31 German women were trapped inside a wooden building. Flames surrounded them….

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft DT

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory in Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

Inside Ford’s Cafeteria: How 1 Kitchen Fed 42,000 Workers Daily — Used More Food Than Nazi Army DT

At 5:47 a.m. on January 12th, 1943, the first shift bell rang across the Willowrun bomber plant in Ipsellante, Michigan….

America Had No Magnesium in 1940 — So Dow Extracted It From Seawater DT

January 21, 1941, Freeport, Texas. The molten magnesium glowing white hot at 1,292° F poured from the electrolytic cell into…

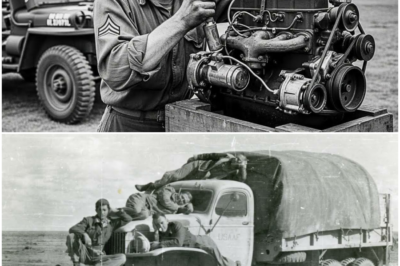

They Mocked His Homemade Jeep Engine — Until It Made 200 HP DT

August 14th, 1944. 0930 hours mountain pass near Monte Casino, Italy. The modified jeep screamed up the 15° grade at…

Beyond the Stage and the Stadium: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Unveil Their Surprising New Joint Venture in Kansas City DT

KANSAS CITY, MO — In a world where celebrity business ventures usually revolve around obscure crypto currencies, overpriced skincare lines,…

End of content

No more pages to load