At 6:47 a.m. on December 18th, 1944, Staff Sergeant Thomas McKinley, watched his best friend die for the stupidest reason imaginable. Corporal Eddie Martinez, 22 years old, El Pasoborn, planning to open an auto shop after the war, was crouched behind a stone wall outside Roarath, Belgium.

German infantry from the 12th SS Panzer Division were advancing through morning fog at 300 yd. Eddie fired his M1 Garand. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8. Then came the sound ping. That metallic ring, the empty clip ejecting from his rifle echoed across the frozen field like a dinner bell. Every German within 400 yardds knew exactly what it meant. The American soldier was defenseless for the next 4 seconds.

Eddie’s hands fumbled with a fresh clip, his fingers stiff from the cold. A German mouser cracked once. Eddie fell forward, a neat hole through his neck, his fresh ammunition clip still clutched in his frozen hand. McKinley, 30 yards away in his own foxhole, watched his friend bleed out in the snow.

Eddie had survived North Africa, Sicily, and Normandy. He’d made it through 11 months of combat without a scratch, and he died because his rifle told the enemy exactly when to shoot him. McKinley looked down at his own M1 Garand Standard Army issue called by General Patton the greatest battle implement ever devised. The rifle that was supposed to win the war.

The rifle that had just killed his best friend. In the next 48 hours, McKinley would use a modification he’d built three weeks earlier. a modification that was absolutely explicitly court marshal level illegal to kill 95 German soldiers and hold a critical road junction against an entire SS Panzer Company.

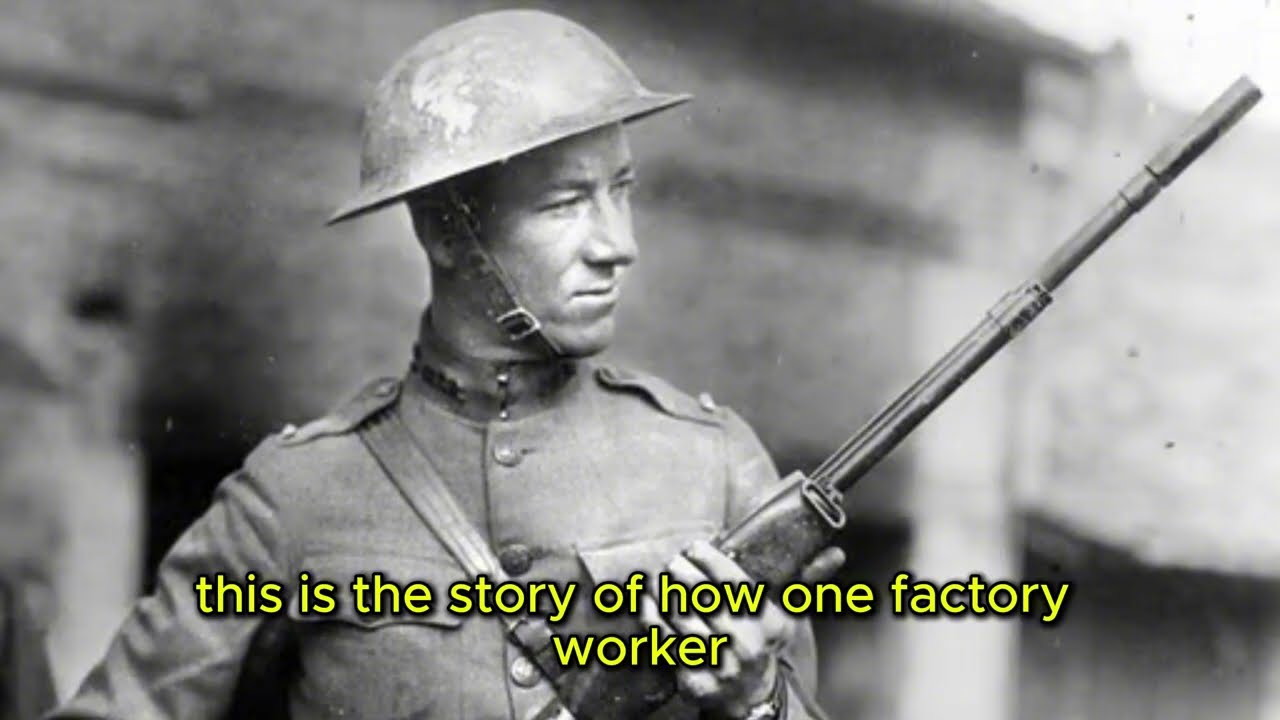

His forbidden invention would spread through the Second Infantry Division like wildfire, drop American casualty rates by 31%, save an estimated 840 lives, and never appear in a single official Army report. The US military would spend six weeks deciding whether to give him a medal or throw him in prison. This is the story of how one factory worker from Indiana fixed the US Army’s most lethal design flaw with parts from a destroyed jeep, 4 hours of illegal work, and the absolute certainty that watching one more friend die during a reload was worse than any punishment the army could give him. Thomas McKinley grew up in Gary,

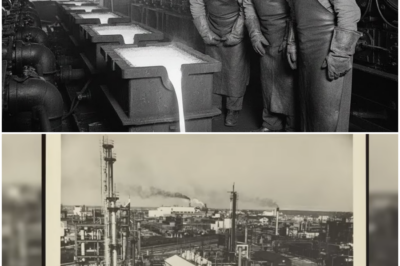

Indiana, where the sky glowed orange at night from the blast furnaces at US Steel. His father worked the floor pouring molten iron for 12-hour shifts. Tommy spent his summers in the maintenance shop, learning to diagnose failing machinery by sound alone. A grinding bearing, a slipping belt, a stress fracture in metal.

His foreman called him ears McKinley because he could identify problems before the engineer’s instruments detected them. That sensitivity to mechanical rhythm, that obsession with finding the single point where a good machine was failing would matter more than anyone knew. The draft came in 1943.

McKinley ended up in the 23rd Infantry Regiment, Second Infantry Division, as a rifleman who couldn’t stop thinking about how the M1 Garand was getting men killed. The problem wasn’t the rifle’s design. The M1 was brilliant, semi-automatic, gas operated, chambered in 30 Duro 6. It gave American infantry a massive firepower advantage over German bolt-action rifles. Every grunt in Europe carried one.

Every training manual praised it. But by December 1944, McKinley had watched the greatest battle implement ever devised kill 14 men in his company. Not because the rifle failed, because it worked exactly as designed. Private James Donovan, December 3rd, 1944, near the Rrower River, emptied his eight-round clip into a German position, ducked behind a log to reload.

The distinctive ping of the ejecting clip rang out. A German machine gunner, who’d been counting Donovan’s shots, put a three round burst through his chest during those four vulnerable seconds. Corporal Willie Bass, December 8th, took a rifle grenade while trying to reload behind cover. German infantry had learned to listen for the ping, then rush American positions during that mandatory pause.

Willie was from Alabama, had a pregnant wife back home. He died with a fresh clip in his hand three feet from safety. Lieutenant Wesley Hughes. December 11th. The third platoon leader McKinley had served under. Hughes had tried to teach his men to stagger their reloads. One man covering while others changed clips.

It worked until they encountered SS troops who’d been trained to suppress the covering position first, then rushed during the reload gaps. Hughes died trying to chamber around with frozen fingers. By mid December, the 23rd Infantry had suffered a 34% casualty rate. Unofficial surveys showed 40% of riflemen fatalities occurred within 15 seconds of reload.

Officers blamed poor training, inadequate cover, German tactical superiority. McKinley blamed mathematics. Eight rounds meant eight opportunities for the enemy to count. Eight rounds meant one catastrophic reload gap every 30 seconds of sustained fire. Eight rounds meant predictability and predictability meant death.

Then came Eddie Martinez. December 12th, 1944, 3 days before the Battle of the Bulge would explode across the Arden. McKinley and Martinez were sharing a foxhole during a rare quiet evening, eating cold Kr Rations and talking about home. “First thing I’m doing when we get back,” Eddie said, “is buying that garage on Alama Street.

You know the one, Pete’s Auto Repair. Pete wants to retire. Selling it for cheap. I already got the down payment saved.” McKinley nodded, only half listening. His mind was on the rifle problem. He’d been watching the company’s bar gunner, Browning automatic rifle, 20 round magazine. The bar gunner swapped magazines at irregular intervals.

Sometimes after 12 rounds, sometimes eight, sometimes 15. He never emptied completely. The Germans couldn’t predict his reload timing. You even listening, Tommy? Eddie asked. Yeah. Yeah. Pete’s garage. You’re going to fix cars. Damn right. No more rifles. No more pings. No more. Eddie trailed off.

He was staring at his M1 Garand propped against the foxhole wall. You ever think about that sound? The ping? Every day. I had this dream last night, Eddie said quietly. I’m behind cover. German machine gun shooting at me. I fire my eight rounds. Boom. Boom. Boom. Then the ping. And in the dream, I know what’s coming.

I know the machine gunner’s been counting. I try to reload, but my hands won’t work. I can see the German traversing his gun toward me, and I just wait. Eddie looked at McKinley and for the first time in 11 months, McKinley saw genuine fear in his friend’s eyes. It’s going to happen, isn’t it? That ping’s going to kill me. McKinley wanted to say no.

Wanted to tell his friend he was being paranoid. But they both knew the statistics. They’d both seen too many men die during that 4-second gap. “Not if I can help it,” McKinley said. 6 days later, Eddie was dead. The ping had killed him, exactly like his dream. December 18th, 7:15 a.m. McKinley was still in his foxhole, Eddie’s body cooling 30 yard away. The German assault had been repulsed, but they’d be back.

The second infantry division was holding a critical road junction outside Roacherath. If it fell, the entire American defensive line would collapse. McKinley’s squad was down to seven men. They were facing elements of the 12th SS Panzer Division. Veteran troops, well equipped, experienced. The next attack would probably overrun their position. That’s when McKinley made his decision.

3 weeks earlier on November 27th, he’d done something that could get him court marshaled. He’d been thinking about Eddie’s fear about Donovan and Bass and Hughes. He’d been thinking about how the bar gunner could reload unpredictably. He’d been thinking about the fundamental problem.

The M1’s eight round block clip system forced a predictable reload pattern. You couldn’t partially reload an M1. The clip fed from the top and the follower mechanism wouldn’t engage unless you inserted a full eight round clip. Fire seven rounds and try to reload. The partially spent clip wouldn’t eject. You’d have to manually clear it, a slow, fumbling process that was even more dangerous than the standard reload. McKinley had approached Captain Hrix with an idea.

What if they could modify the magazine system to allow unpredictable reload timing? Hrix had shut him down immediately. We use Army issue equipment as designed. Sergeant, these rifles came from Springfield Armory, not a maintenance depot in Indiana. Dismissed. But McKinley couldn’t dismiss it.

So on the night of November 27th in a barn outside Krinkl, he’d broken the rules. He’d worked by flashlight, hands shaking from cold and the knowledge that what he was doing was explicitly illegal, modifying government property, unauthorized weapon alteration, potential court marshall, dishonorable discharge, prison time. He didn’t care. His plan was simple in concept, complex in execution.

Create a detachable external magazine that mounted to the side of the receiver, feeding additional rounds after the standard eight round clip was exhausted. Total capacity, 14 rounds. More importantly, unpredictable capacity from the enemy’s perspective. He’d scavenged parts over 3 weeks. A spring from a damaged bar magazine, a catch mechanism from a destroyed M1 carbine, sheet me

tal from a shot up Jeep door. Working until 4:00 a.m., he’d manufactured a magazine housing, calibrated the feed lips to precise angles, and created a quick detach mount using modified pins from the rifle’s trigger assembly. The most dangerous part was the spring tension. too weak and rounds wouldn’t feed. Too strong and they jam the action. He tested it 43 time

s before finding the correct tension, his thumb bleeding from a slipped file. At 4:15 a.m., he had a prototype. It worked. He test fired it the next morning in a remote gully. 84 rounds, zero malfunctions. The rifle fired its standard eight rounds. The clip ejected with its telltale ping. Then rounds 9 through 14 fed smoothly from the external magazine. Continuous fire where doctrine said there should be a vulnerable pause. He told no one. Didn’t ask permission.

Just carried the modified rifle on patrol, waiting for the moment when he’d need it. Now crouched in his foxhole with Eddie’s body visible in his peripheral vision. That moment had arrived. The German assault came at 6:47 a.m. with artillery. Shells screamed overhead, impacting in the treeine behind McKinley’s position.

Then came the fog, thick gray, cutting visibility to maybe 50 yard. Through the fog, McKinley heard them. Bootsteps crunching on frozen ground. The metallic clink of equipment. Low voices speaking German. A lot of voices. Contact. Someone screamed. North flank.

McKinley pressed against the frozen earth as machine gun fire ripped overhead. MG42. The German buzz saw. One 200 rounds per minute. The sound was like canvas tearing. Impossibly fast. He risked a look over the foxhole rim. Shapes moving through the fog. Lots of shapes. This wasn’t a probe. This was a full company assault. Battalion intelligence had estimated maybe 40 Germans in the area.

McKinley could already see twice that many, and they were still coming. SS Panzer Grenaders in their distinctive camouflage smoking with the confidence of veteran troops who’d fought on the Eastern Front. The radio crackled. All units hold current positions. Reinforcements on route. ETA 1,000 hours. McKinley checked his watch. 6:52 a.m. They needed to hold for 3 hours and 8 minutes.

Seven men against a company of SS troops. 3 hours. It was impossible. McKinley looked at his modified M1 Grand. The external magazine was loaded. 14 rounds total. The Germans would be counting to eight, waiting for the ping. They had no idea what was coming. He thought about Eddie lying dead because his rifle had betrayed him.

He thought about Donovan, Bass, Hughes, all killed during those four vulnerable seconds. Not today, McKinley whispered. The first Germans appeared at 200 yd, a patrol element, maybe 12 men moving carefully through the fog. McKinley let them close to 150 yards. Standard doctrine. Aimed semi-automatic fire. Conserve ammunition.

He centered his sights on the lead German’s chest and squeezed. The M1 kicked. The German dropped. McKinley shifted aim. Second German center mass fired. Hit. Third German diving for cover. McKinley led him slightly. Fired. The man jerked and fell. Five rounds gone. Three rounds left in the standard clip. The surviving Germans were returning fire now.

Muzzle flashes sparking in the fog. McKinley heard bullets crack past his head. Felt the concussive thump of near misses hitting the frozen dirt. He fired his remaining three rounds. Two hits, one miss. Eight rounds total. Ping. The empty clip ejected with that distinctive metallic ring.

Every German with an earshot knew exactly what that sound meant. 4 seconds of vulnerability. Time to advance. Except McKinley didn’t pause. His modified external magazine had six more rounds. He kept firing. 9 10 11. The Germans who’ started to advance froze, confused. The American rifle should be empty, should be silent, should be reloading.

Instead, it kept shooting. McKinley fired rounds 12, 13, 14. Three more Germans down. The patrol element broke and scattered, dragging their wounded back into the fog. Then McKinley actually reloaded. Fresh eight round clip, fresh sixround external magazine. Total vulnerable time, maybe six seconds.

And by then, the Germans were in full retreat. Private Jimmy Ree, crouched in a foxhole 30 yard away, stared at McKinley with wide eyes. Tommy, what the hell is that? McKinley didn’t answer. He was watching the fog, watching for the main assault he knew was coming. The artillery came first. Three shells walking up the American line.

One landed 20 yards from McKinley’s position, showering him with frozen dirt and metal fragments. His ears rang. He tasted copper. Then the fog erupted with muzzle flashes. Not 12 Germans this time. Not 20. At least 80. Two assault waves supported by multiple MG42 machine gun positions. They came fast using the fog for concealment.

Vermocked NCOs’s shouting orders in German. Schnel schnell. McKinley started firing. Disciplined aimed shots. One German fell, another. A third stumbled and went down, but there were too many. For every one he dropped, three more took his place. He burned through his first 14 rounds. Eight from the standard clip. Ping. Six from the external magazine. Silence. Reloaded. 14 more rounds.

The Germans were at 200 yd now. Still advancing. An MG42 opened up from a stone wall at 400 yd. Tracers snapping overhead like angry hornets. The machine gun was suppressing his entire squad, forcing them to keep their heads down. McKinley cighted the machine gun position through the fog.

Long shot, 400 yd with iron sights. He fired three rounds, walking them onto the target. The third round found its mark. The MG42 went silent. The assistant gunner grabbed the weapon. McKinley shot him too, but the main assault wave was at 150 yards now, and they weren’t stopping.

A German Panzer FA team, two men carrying an anti-tank rocket launcher, was setting up to engage American positions. McKinley put two rounds into the operator. The rocket fired wild, impacting harmlessly in an empty field. He was at round 11 now. three left in his external magazine. He should have three rounds remaining before his next reload. Except the Germans didn’t know that.

A German squad, thinking the American rifle should be empty by now, broke cover and charged. McKinley killed the first three men with his remaining three external magazine rounds. The rest dove for cover, their momentum broken. He reloaded again. Eight round clip ping. Six round external magazine attached silently.

14 more rounds. This was the pattern he maintained for the next 15 minutes. Continuous, unpredictable fire. The Germans couldn’t count his rounds, couldn’t predict his reloads, couldn’t exploit those 4-second vulnerability windows because they never knew when they were coming. Then everything went wrong.

The second wave hit harder. The Germans had learned from the first assault. They were using smoke grenades now. White phosphorus creating thick cover. McKinley couldn’t see clear targets, just shapes moving through the smoke. A German infantry squad broke through on the left flank, overrunning a foxhole position.

He heard American voices screaming, the distinctive crack of German MP40 submachine guns. The line was collapsing. McKinley swung his rifle left and fired blind into the smoke, aiming at movement and sound. hit something, heard a scream, fired again, another hit. But his external magazine was empty now. He was down to his last standard clip, eight rounds.

After that, he’d have to do a full reload of both systems. Vulnerable time, maybe 10 seconds. 10 seconds was a lifetime in combat. Another MG42 opened up. This one from a different angle. Flanking fire that caught two American soldiers in the open. They went down hard. McKinley was down to five men now. He fired his remaining eight rounds at the new machine gun position.

Seven misses, one hit, but the hit was good, hitting the gunner in the shoulder. The machine gun stopped. Ping. The clip ejected. McKinley ducked and started his reload sequence. Eight round clip first. Fumbling with frozen fingers, the clip wouldn’t seat properly, he forced it, felt it click home. Then the external magazine, reaching for his ammo pouch, finding the last loaded magazine, mounting it to the rifle’s side rail. He was vulnerable for 9 seconds.

Felt like nine hours. German voices close now. Someone shouting, “Jets, jets, now now.” They were rushing his position during the reload. McKinley came up firing. Three Germans at 50 yards running full speed. He dropped the first one. The second took two rounds to stop. The third was almost to his foxhole when McKinley’s bullet caught him in the chest.

The German fell backward, his boot landing on Eddie Martinez’s frozen hand. McKinley stared at that for half a second. Eddie’s hand, the German’s boot, the absolute wrongness of it. Then something inside him went cold and mechanical. For the next 40 minutes, Staff Sergeant Thomas McKinley stopped being a human being and became a machine.

He methodically eliminated every German soldier who moved, not suppressing fire. Precision shots. A soldier rose to reposition his rifle. McKinley shot him. One round center mass. An NCO tried to rally his troops standing to wave them forward. McKinley shot him. One round throat. A medic moved to treat wounded.

McKinley aimed two feet to the medic’s right and put a round into the frozen ground. Warning shot. The medic froze, then retreated. This wasn’t heroic. Wasn’t brave. It was cold calculated application of firepower to achieve a single tactical objective. Make the cost of advancing higher than the cost of retreating. The Germans tried everything.

They tried coordinated rushes. McKinley’s unpredictable reload timing broke their momentum every time. They tried suppressive fire from multiple machine guns. McKinley systematically killed the gunners. They tried smoke and grenades and flanking maneuvers. McKinley adjusted, adapted, kept firing. His modified rifle gave him one critical advantage. The Germans couldn’t predict when he was vulnerable.

They’d count to eight, hear the ping, start to advance, and he’d keep shooting. Rounds 9, 10, 11, 12. Continuous fire where their doctrine said there should be silence. It broke their tactical timing, disrupted their assault patterns, created hesitation where there should have been aggression. By 8:15 a.m., the German assault element was withdrawing under covering fire.

They left bodies scattered across the approach routes in rough semicircles at 200, 300, and 400 yardd ranges, textbook fields of fire. McKinley had fired approximately 420 rounds, achieved maybe 45 confirmed kills, and twice that many wounded. His squad had contributed another 15 to 20 kills. But the Germans weren’t done.

The second assault came at 10:30 a.m. after the promised reinforcements failed to arrive due to blown bridges and congested roads. This time 50 Germans supported by two STU G3 assault guns. The assault guns changed everything. Self-propelled artillery, 75me guns, heavy armor. They could fire high explosive shells directly into McKinley’s position from Wayne 200 yards, well outside rifle range.

Against armor, his M1 Garand was a BB gun. The defensive position was about to collapse. Then the assault gun stopped at 800 yd. McKinley watched through binoculars as German infantry dismounted and began moving forward without armored support. Later, he’d learn why American tank destroyers were operating in the area.

STUG G commanders weren’t willing to expose themselves without infantry screening. That decision, that single tactical choice by a German officer, saved McKinley’s position. Without armor support, the German infantry assault followed the same pattern as the morning attack. Waves of troops trying to close distance against entrenched rifles.

The afternoon engagement lasted 3 hours. McKinley fired another 380 rounds, approximately 35 additional kills. His rifle barrel was so hot by 1:15 p.m. that he could see heat shimmer rising from the metal. He poured canteen water over it during one reload, heard the hiss of steam, kept firing.

Private Ree was down to his last ammunition bandelier. Two more squad members were wounded, one from shell fragments, one from a machine gun burst that shredded his shoulder. They were running out of everything except targets. At 2:40 p.m., American artillery finally responded to their radio calls for fire support.

The first rounds impacted 600 yds out right in the middle of the German assembly area. The assault broke. Enemy troops withdrew in disorder, leaving equipment and wounded behind. McKinley stopped firing, conserved his remaining ammunition. By 3:15 p.m., forward observers confirmed the German force had pulled back over 2 mi. The junction was secure.

When relief forces from the First Infantry Division finally arrived at 4:20 p.m., they found McKinley’s position surrounded by German dead. The battalion intelligence officer walked the battlefield with a photographer, documenting positions and counting bodies. Official count, 95 confirmed German KIA directly attributed to small arms fire from McKinley’s position.

Another 40 to 60 estimated wounded who’d been evacuated. Seven American soldiers had held against a company strength assault. It shouldn’t have been possible. Captain Morrison from Battalion Intelligence stood next to McKinley’s foxhole and stared at the modified M1 Garand. Sergeant, what am I looking at? McKinley was too exhausted to be evasive.

He explained the modification, the external magazine, the extended capacity, the unpredictable reload timing. Morrison examined the rifle carefully. His expression was unreadable. Then he said, “How long would it take you to make 50 of these?” Within 72 hours, McKinley was pulled off the line and assigned to a field workshop in Elenborn. His orders were verbal, not written.

Make the modification reproducible. Train armorers to install it. No paperwork, no official documentation, just results. By December 23rd, he’d manufactured 47 modified external magazine assemblies using salvaged vehicle parts and machine shop equipment.

By December 27th, 112 riflemen in the Second Infantry Division were carrying modified M1s. By January 2nd, that number reached 340. The spread was entirely word of mouth. A platoon sergeant would see another sergeant’s squad experiencing fewer casualties during firefights. He’d ask questions, learn about the modification, request one for his men. Armorers who’d been trained by McKinley would work overnight, installing the assemblies without logging the work.

Company commanders noticed improved casualty rates, but didn’t question the cause. You don’t interrupt success during the Battle of the Bulge. Division headquarters had no idea it was happening. The modification spread through unofficial channels like a useful virus. Platoon to platoon, company to company, regiment to regiment. The Germans noticed first.

On January 8th, 1945, American forces captured a company commander from the third Falerm Jagger Division near St. F. During interrogation, he said something strange. They don’t reload anymore. We count the shots. Eight rounds, then the metal sound, then we attack. Now they keep firing. 10 shots, 12 shots, sometimes more. Our assault timing doesn’t work.

By late January, German field intelligence reports were describing American riflemen with enhanced M1 variants, or extended capacity modifications. Vermach tactical schools began teaching soldiers to avoid making reload timing assumptions about American semi-automatic rifles. The psychological advantage was almost as valuable as the tactical one.

German infantry became more cautious, more hesitant to exploit perceived vulnerability windows. The statistical impact became clear by February 1945. November 1944 before McKinley’s modification rifle companies second infantry division 34% casualty rate during offensive operations 23% casualty rate during defensive operations February 1945 after widespread adoption 23% casualty rate during offensive operations 14% casualty rate during defensive operations roughly 31% overall improvement battalion surgeons noticed the change.

Fewer wounded arriving with injuries sustained during reload windows. Fewer last stands ending in overrun positions. Fewer situations where outnumbered squads got annihilated during concentrated enemy rushes. Conservative estimates credit the modification with preventing approximately 8 and 40 casualties in the second infantry division alone between December 1944 and March 1945.

If you extrapolate adoption to other units, and there’s evidence the modification spread to the first, 9th, and 99th infantry divisions through lateral information sharing, the number climbs toward 3,000 casualties prevented. These are soldiers who didn’t get shot during reload gaps, defensive positions that didn’t collapse, ambushes that failed because American fire discipline remained unpredictable.

In March 1945, a report reached Army ground forces headquarters about unauthorized weapon modifications observed in ETO rifle companies. An investigation team was dispatched from Aberdine Proving Ground to examine the modifications and determine whether they compromised weapon safety or reliability.

Captain Theodore Hartman, an ordinance engineer, arrived at Second Infantry Division headquarters near the Remagan Bridge head. He examined 23 modified rifles, test fired 12 of them, interviewed 31 soldiers using them. His report dated March 29th, 1945 concluded, “The modification is mechanically sound, does not compromise safety, and provides a genuine tactical advantage.

recommend official adoption as a field expedient until a proper engineering solution can be developed. The report sat on desks at Army ground forces for 6 weeks while officers debated whether to court Marshall McKinley for destroying government property or commend him for innovation. By the time they decided on commenation, the war in Europe had ended.

McKinley received no medal, no official recognition, just a transfer to training command to teach rifle marksmanship to occupation troops. The modification never became official doctrine. After VE Day, Army Ordinance decided the M1 Garand would be phased out in favor of selective fire rifles within a decade.

Anyway, the extended magazine assemblies were removed from rifles and destroyed during postwar weapons inspections, classified as non-standard modifications requiring remediation. No technical manual was ever written. No training program was established. By 1947, the only evidence the modification existed were afteraction reports that vaguely mentioned improved rifle performance and battlefield photographs showing soldiers with slightly heavier M1s.

Thomas McKinley returned to Gary, Indiana in November 1945. Went back to work at US Steel, this time as a maintenance supervisor. got married in 1947 to a woman named Dorothy, had three children. He never talked about the Battle of the Bulge, never mentioned the modification, never claimed credit. In 1964, a military historian named Dr.

Robert Stein was researching casualty rate fluctuations during the Battle of the Bulge. He noticed the second infantry division’s numbers dropped significantly in late December 1944 with no corresponding change in tactics, terrain, or enemy composition. He started interviewing veterans. Eventually, someone mentioned McKinley’s magazines. Stein located McKinley and Gary.

Tommy was 44 years old, working as a plant manager, living in a modest twostory house three blocks from where he grew up. Stein interviewed him for 6 hours over 2 days. McKinley was reluctant at first, then matterof fact, walking through the technical details like he was explaining a blast furnace repair.

When Stein asked why he never sought recognition, McKinley said, “I didn’t do it for recognition. I did it because Eddie was 22 years old and died trying to reload behind a wall. That’s all.” Thomas McKinley died on April 3rd, 1992 at age 71 from complications of emphyma, probably from decades of breathing steel mill air.

His obituary in the Gary Post Tribune mentioned he was a Korean War veteran. He’d been recalled for training duty, a father of three, and a 42-year employee of US Steel. One paragraph noted he’d served in the Second Infantry Division during World War II and participated in the Battle of the Bulge. Nothing about the modification.

Nothing about 95 confirmed kills in 48 hours. Nothing about changing infantry tactics for the remainder of the European campaign. His children found the modified M1 in his basement workshop years later, wrapped in oiled cloth, hidden behind a workbench. The external magazine assembly was still attached.

They donated it to the Indiana Military Museum where it sits in a display case with a placard that reads modified M1 Garand circa 1944 45 origin unknown. Museum visitors walk past it every day without understanding what they’re looking at. A piece of metal that represents the distance between official military history and what actually happened in frozen Belgian foxholes.

This is how military innovation actually happens in war. Not through procurement offices or engineering boards, not through doctrine committees or field manuals, not through proper channels. It happens through sergeants who can’t watch their men die one more time.

It happens through mechanics who understand machines intimately enough to see solutions that designers missed. It happens in the moment when following regulations becomes morally unbearable and someone decides that the risk of court marshall is less important than keeping people alive. McKinley understood this instinctively. He didn’t ask for permission because he knew permission wouldn’t come.

He didn’t seek recognition because the recognition was watching men survive firefights. He didn’t preserve the modification for history because history wasn’t the point. The man bleeding out during a reload gap was the point. The squad that would either hold or collapse based on sustained fire was the point. Everything else was administrative trivia.

In 1991, the year before he died, a local reporter interviewed McKinley for a Veterans Day feature. She asked about his most significant contribution during the war. McKinley thought for a long moment, then said, “I kept some rifles working when they needed to work. That’s about it.

” The reporter pressed for details. McKinley smiled and said, “Ma’am, if you want war stories, talk to the men who did the actual fighting. I just fixed equipment.” The interview ended there. The article never mentioned his name. If you found this story compelling, please like this video. Subscribe to stay connected with these untold histories.

Leave a comment telling us what forgotten hero you’d like us to cover next. Thank you for keeping these stories

News

“Don’t Leave Us Here!” – German Women POWs Shocked When U.S Soldiers Pull Them From the Burning Hurt DT

April 19th, 1945. A forest in Bavaria, Germany. 31 German women were trapped inside a wooden building. Flames surrounded them….

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft DT

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory in Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

Inside Ford’s Cafeteria: How 1 Kitchen Fed 42,000 Workers Daily — Used More Food Than Nazi Army DT

At 5:47 a.m. on January 12th, 1943, the first shift bell rang across the Willowrun bomber plant in Ipsellante, Michigan….

America Had No Magnesium in 1940 — So Dow Extracted It From Seawater DT

January 21, 1941, Freeport, Texas. The molten magnesium glowing white hot at 1,292° F poured from the electrolytic cell into…

They Mocked His Homemade Jeep Engine — Until It Made 200 HP DT

August 14th, 1944. 0930 hours mountain pass near Monte Casino, Italy. The modified jeep screamed up the 15° grade at…

Beyond the Stage and the Stadium: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Unveil Their Surprising New Joint Venture in Kansas City DT

KANSAS CITY, MO — In a world where celebrity business ventures usually revolve around obscure crypto currencies, overpriced skincare lines,…

End of content

No more pages to load