At 6:47 a.m. on August 1st, 1943, Lieutenant Colonel Addison Baker and Major John Gerstad climbed into B24 Liberator Hell’s Wench at Benghazi airfield in Libya as 178 heavy bombers prepared for the longest and lowest bombing raid in history. Baker was 36 years old, commanding officer of the 93rd bomb group with 11 months combat experience.

Jerstad was 25, had already completed his required 25 missions 3 weeks earlier, and had volunteered to fly this mission as Baker’s co-pilot. The target was Powesti oil refineries in Romania, facilities that supplied 30% of Nazi Germany’s fuel, and intelligence predicted 50% casualties before the day ended.

Operation Tidal Wave required a 2400m round trip at altitudes between 50 and 500 ft, treetop level. The Luftwaffa and German anti-aircraft crews had transformed Pestgi into the most heavily defended target in Europe. Previous highaltitude raids had failed. The only way to destroy the refineries was to fly directly through the defenses at chimney height. Drop delayed fuse bombs.

Hope the explosions didn’t catch your own aircraft. The Eighth Air Force had lost 47 B-24s during training exercises for this mission. Pilots misjudged altitude over water, flew into hillsides during low-level practice runs, collided in tight formations. Command estimated they would lose 90 aircraft over the target. That meant 900 men.

Baker knew these numbers. Gerstad knew them, too. He’d finished his tour, could have returned home to Oregon. Instead, he’d asked to fly one more mission. Baker needed experienced pilots. Jerstad was operations officer, understood the mission plan better than anyone except Baker himself. Will they survive what’s coming? Please hit that like button. It helps more people discover these stories.

And subscribe back to Baker and Jerad. Hell’s Wench carried 10 crew members that morning. Navigator Harold Sweetman, bombardier John McCormack, engineer James Merritt, radio operator Cecil Fight. Four gunners. Every man understood the statistics. One in two aircraft wouldn’t return. But Pesti produced 12 million barrels of refined petroleum annually.

Every day those refineries operated, German tanks rolled deeper into Russia. Yubot hunted Allied convoys. Messers intercepted bomber formations over Germany. Destroying Pesti could shorten the war by months, save thousands of Allied lives. The mission was worth the cost. Baker had briefed his group three times. Emphasize timing. The entire attack depended on five bomb groups reaching their targets simultaneously at exactly 9:30 a.m.

Romania time. Spread defensive fire. Overwhelm anti-aircraft crews. Any delay meant concentrated defenses. Any deviation from the flight plan meant disaster. Each group had specific refineries to hit. The 93rd would attack the Astro Romana and Nunria refineries. Baker’s aircraft would lead the formation. Set the example, show his men the way through.

At 7:00, engines thundered across Benghazi airfield. 178 B-24s lifted into the morning sky, formed up over the Mediterranean, turned north toward Romania. The formation stretched for miles, 19,000 ft altitude. Initially they would drop to wavetop height over the Aian sea. Stay low across Greece and Yugoslavia. Reach Pyesti below German radar. Baker settled into his seat.

Gerstad took the co-pilot position. Hell’s Wench flew in the lead spot. 17 aircraft from the 93rd followed directly behind. 3 hours into the mission. A B24 from the lead navigation group lost power over the Mediterranean. The aircraft carrying the mission’s lead navigator. It descended toward the water, attempted an emergency landing.

The bomber hit waves at 140 mph, disintegrated. All crew lost. The entire operation had just lost its Pathfinder. No backup navigator knew the complete route. Baker watched the formation continue north. Something was already wrong. The formation crossed the Greek coast at 9,000 ft, descended to 500 ft over Yugoslavia.

B-24s flew so low that pilots could see individual trees. Sheep scattered as bombers roared overhead. The plan called for terrain masking. German radar stations couldn’t track aircraft flying below hilltops, but low altitude meant fuel consumption increased. Navigational errors became critical. A wrong turn at this altitude could send the entire formation into mountainside. Baker checked his instruments.

Fuel consumption normal, engines running steady. Behind him, 17 B-24s from the 93rd maintained tight formation. To his left and right, other bomb groups spread across the sky. The 44th, the 98th, the 76th, the 376th. Five groups, 177 aircraft still flying, one target 30 mi

nutes away. At 9:05 a.m. Romania time, the formation reached the initial point near Pesti, the IP, the spot where bombers would turn east toward Pesti. This was the critical navigation moment. Every group needed to identify landmarks, turn at precisely the right moment, follow the correct valleys toward their assigned refineries. Without the lead navigator, the mission commander’s aircraft took over navigation duties. Baker watched the lead group begin their turn. They turned toward Bucharest. Wrong city.

Wrong direction. Baker recognized the error immediately. The lead group had mistaken one valley for another. A simple navigational mistake at 500 ft altitude. But Bucharest lay 30 mi southeast of Pesti. The lead group was taking three bomb groups, over 100 aircraft, away from the target, away from the mission. The attack plan was collapsing.

Baker grabbed the radio transmitter, tried to contact the mission commander. Radio discipline had been strict throughout the flight. Minimal transmissions. German listening posts were tracking them, but this was an emergency. The mission was about to fail. Baker called repeatedly. No response.

Either the lead aircraft wasn’t monitoring the frequency or they couldn’t hear through radio interference. German jamming had started the moment the formation crossed into Romania. Static filled the airwaves. Jarstad looked at Baker. The decision was simple. Follow the lead group to the wrong target and waste the entire mission. Or break formation. Turn the 93rd toward Plawi alone.

lead his 17 aircraft into the most heavily defended target in Europe without the planned support from other groups. No simultaneous attack, no split defenses. Every German gun would focus on the 93rd. Command had predicted 50% losses with the full formation attacking together. What would losses be with one group attacking alone? Baker made his decision in 5 seconds.

He banked Hell’s Winch hard left away from the lead group toward Plawesti. behind him. Every aircraft in the 93rd followed. 17 B24s broke from the main formation. The original attack plan called for 94 bombers hitting Pawesti together. Now Baker was leading 18 bombers toward targets designed to be attacked by five times that number. German radar operators watched the formation split. Flack battery commanders received urgent updates.

American bombers approaching from the south. Small group, 18 aircraft. Altitude 500 ft. Speed 210 mph. Every available gun crew in Plesti received the same order. Concentrate all fire on this group. Stop them before they reach the refineries. Baker flew toward the smoke stacks of Astro Romana. 11 mi ahead. 10 minutes flying time. Gerstad scanned the horizon through the co-pilot window.

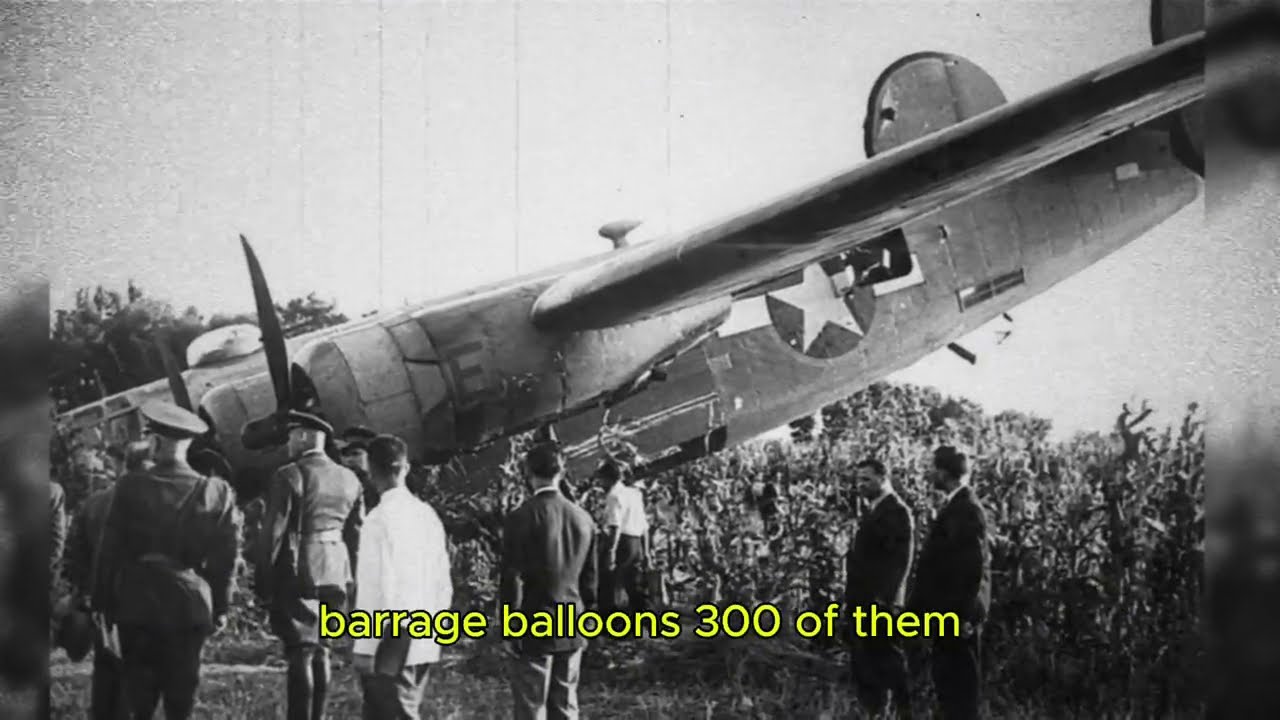

Black smoke already rising over the city. Something else too. Small dark shapes lifting from the ground around the refineries. Dozens of them. Then hundreds. Barrage balloons. Steel cables dangling beneath them. Designed specifically to destroy low-flying bombers.

The cables would shred wings, tear through fuselage, rip engines from mountains. Pesti defenders had raised every balloon in the city. Hell’s wench was flying directly into a forest of steel. At 9:17 a.m., Hell’s Wench entered the Pesti defense zone at 470 ft altitude. The city sprawled ahead.

Seven major refineries, miles of pipelines, cracking towers, storage tanks, smoke stacks belching black smoke, and above everything, barrage balloons. 300 of them. Steel cable stretched from ground to balloon. Each cable designed to catch aircraft wings, snap them off, send bombers tumbling into the ground. Baker had no choice about altitude. The mission required bombing from chimney height. Delayed fuses needed time to arm.

If they dropped from normal bombing altitude, the bombs would explode before penetrating deep into refinery structures. The entire mission depended on flying low, flying through those cables. The 93rd crews had trained for this. Practiced low-level bombing runs over desert targets in Libya, but training targets didn’t shoot back.

Training balloons didn’t have steel cables. Behind Hell’s Wench, 17 B24s followed in tight formation. Nose gunners tracked the balloons ahead. Top turret gunners searched for fighters. The Luftwaffa had stationed 200 fighters at airfields around Pesti. Messers 109s, Faula Wolf 19As, Romanian IAR81s.

Intelligence had predicted waves of fighter attacks during the bomb run. So far, no fighters appeared. German commanders were holding them back, waiting. The flack batteries would handle the bombers first. The first 88 mm shell exploded 200 ft ahead of Hell’s Wench. Black smoke, orange flash. Shrapnel sprayed outward. Baker flew through the blast. The aircraft shuddered. More explosions erupted across the sky.

German gun crews had the range. The Powesti defenses included 230 flat guns, 88s, AAA batteries, machine gun nests on rooftops, every gun opened fire simultaneously. The sky filled with tracers, red lines streaking toward the formation, black puffs of exploding shells. The barrage was so dense that pilots couldn’t see through it.

A balloon cable appeared directly ahead. Baker yanked the controls left. Hell’s wench banked hard. The cable passed 20 ft from the right wing. Another cable to the left. Baker rolled right. Flying through the forest, dodging cables that appeared without warning through the smoke. Durststead called out positions.

Cable high left. Cable low right. Baker flew by instinct. The refineries were 3 mi ahead. Three more minutes. The formation had to stay together. Had to reach the target. An 88 shell detonated beneath Hell’s Wench. The explosion lifted the aircraft 30 ft. Shrapnel tore through the belly.

Punctured fuel tanks, ripped through hydraulic lines. Red warning lights flashed across the instrument panel. Fuel pressure dropping in number three engine. Oil temperature rising in number one. The aircraft was bleeding. But the engine still ran. The control still responded. Baker kept flying. 2 mi from target. Another barrage balloon ahead.

Baker aimed between two cables. Calculated the gap. 40 ft clearance on each side. Enough room. He committed to the path. Then the aircraft jolted. Hard impact on the right wing. The B-24 had clipped a cable Baker hadn’t seen. The steel wire scraped along the wing leading edge. Tore aluminum. The wire caught on the outboard engine necessel held.

The balloon was now attached to Hell’s wench. 300 lb of rubber and canvas dragging on the right wing, creating massive asymmetric drag. The aircraft pulled right. Baker fought the controls, struggled to maintain heading. Another shell exploded. This one struck directly. An 88 mm round hit the right wing route, punched through the fuel tank. Aviation gas sprayed into the engine compartment.

Hot metal sparking electrical systems, leaking fuel. The mixture ignited instantly. Orange flames erupted from the wing, spread toward the fuselage. Hell’s wench was on fire. One mile from target, 60 seconds to the release point, Baker looked down, saw an open field below, flat, clear, perfect for emergency landing.

They could set down safely, the entire crew could survive, or they could continue the bomb run. Baker kept the nose pointed at Astro Romana Refinery. The fire spread across the entire right wing. Flames reached back toward the fuselage. The metal skin glowed red. Temperature inside the cockpit climbed. Smoke filled the interior. The crew could bail out.

Open field below meant everyone could parachute safely. Or Baker could set the aircraft down, execute emergency landing, walk away. Mission failed. But 17 B24s were following directly behind Hell’s Wench. If Baker landed now, those aircraft would follow. The entire 93rd would abort. The mission would fail completely. Jerstad knew the calculation.

He’d flown 25 missions, survived the odds, earned his ticket home. Now he sat in a burning bomber with a choice. Survival or mission. He didn’t reach for the bailout lever. Didn’t suggest landing. He checked the bomb release panel. Verified the delayed fuses were armed. Prepared for the drop. Baker understood. They were continuing. The flames grew worse.

Fire consumed the right wing from engine to cell to wing tip. The aluminum structure began failing. Rivets popped from heat stress. Metal panels curled. The wing was disintegrating, but it still produced lift. The aircraft still flew. 45 seconds to target. The Bombay doors were already open. Bombardier John McCormick lay prone in the nose. Watched the refinery approach through the Nordon bomb site.

Cracking towers, storage tanks, pipeline networks. The primary structures were dead ahead. Behind Hell’s Winch, the 93rd formation held together. Every pilot saw the flames. Every crew knew their lead aircraft was dying. But Baker hadn’t turned away, hadn’t landed. The formation followed. 17 B24s flew through the flack barrage, through the balloon cables, through smoke so thick that visibility dropped to 100 ft.

They followed Hell’s Winch because Baker and Jerstad were still flying. German gunners concentrated their fire on the burning bomber. every tracer, every shell. If they stopped the lead aircraft, the formation would break apart. 88 rounds exploded continuously around Hell’s Wench. One shell detonated so close that shrapnel shredded the left horizontal stabilizer. The aircraft yawed violently.

Baker fought the controls, used rudder and aileron together, kept the nose steady. The bomb site required stable flight. Any deviation meant missed target, wasted mission, wasted lives. 30 seconds. The refineries filled the windscreen. Cracking towers rose 300 ft high. Hell’s wench flew between them at 400 ft altitude. Wings level. Speed steady.

The fire had now reached the fuselage. Flames licked along the cockpit windows. Paint blistered. Glass cracked from heat. Oxygen masks provided breathable air, but the temperature was unbearable. Baker’s hands were blistering on the control yolk. He held course. McCormick centered the crosshairs.

The delayed fuse bombs would penetrate buildings before exploding, cause maximum structural damage, destroy the refining equipment. He waited for the precise release point, calculated drop trajectory, accounted for wind, altitude, speed. The numbers aligned. He pressed the release. 4,000 lb of high explosive dropped from the bomb bay fell toward the Astro Romana facility.

Hell’s wench lurched upward as the weight released behind Baker. The formation released simultaneously. 18 aircraft, 72,000 lb of bombs. The delayed fuses meant the explosions would occur in waves. First bombs penetrating deep into structures, then detonating, then the next wave, then the next.

The entire refinery was about to be destroyed, but Hell’s Wench was still in the blast radius. Baker pulled back on the yolk, tried to gain altitude, get above the coming explosions. The right wing barely responded. Fire had destroyed the control surfaces. The aircraft climbed slowly, 100 ft per minute, not enough. The bombs would detonate in 18 seconds. The blast radius extended 1,000 ft.

Hell’s wench was 400 ft above ground, 500 ft past the target, still climbing, still burning. The wing structure was failing. The fire had reached the center fuel tanks, and below, 18 seconds had just expired. The first explosion erupted beneath Hell’s Wench. A delayed fuse bomb detonated inside the main cracking tower. The structure disintegrated. Steel beams shot outward.

The blast wave hit the burning B24 like a physical wall. The aircraft tumbled, rolled 30° right. Baker fought the controls, leveled the wings. More explosions followed. Sequential detonations as bombs penetrated deep into refinery buildings before exploding. The entire Astro Romana facility was collapsing. Fireballs rose 300 ft. Black smoke mushroomed upward. The 93rd had hit the target perfectly.

Behind Hell’s Wench, the formation scattered. Each B24 peeled away from the target area, sought escape routes through the flack, through the smoke, through the balloon cables. Some aircraft made clean breaks, climbed rapidly, turned south toward Libya. Others weren’t as fortunate.

A B24 from the 93rd hit a balloon cable at full speed. The wire caught the left wing, sheared it off completely. The bomber rolled inverted, crashed into a storage tank, exploded. 10 men dead instantly. Another B24 took a direct hit from an 88 shell. The round penetrated the Bombay, detonated the remaining bombs still on their racks. The aircraft vanished in an orange fireball.

Fragments scattered across 200 yards. No parachutes, no survivors. A third bomber flew directly through a flack barrage. 20 mm round stitched across the fuselage killed the pilot, wounded the co-pilot. The aircraft nosed down, struck the ground at 200 mph, cartwheelled through a residential area. 14 civilians died alongside the crew.

The 93rd was paying the predicted price. Command had estimated 50% casualties with full formation support. Baker’s group was attacking alone with 1/5ifth the planned aircraft against the full defensive capability of Paweshest. The mathematics were brutal. 18 bombers entered the target zone. Four were already gone. 40 men dead.

The survivors were still fighting their way out. Hell’s Wench climbed through the smoke at 800 ft, still burning. The right wing was completely engulfed. Flames had spread to the fuselage. The cockpit filled with black smoke. Visibility zero. Baker flew by instruments alone. Air speed. Altitude heading. The gauges showed critical damage. Number three engine seized. Number four losing oil pressure. Number one running hot.

Only number two operated normally. The aircraft was flying on one functioning engine and three dying ones. Jerstad scanned the instruments, checked fuel levels. Both right-wing tanks were empty, ruptured by flack. Leaking fuel had fed the fire. The leftwing tanks showed half capacity. Maybe 30 minutes flying time remained. The Mediterranean coast was 90 minutes south. They wouldn’t make it.

The aircraft was dying. But they’d climbed to 800 ft, high enough for parachutes to deploy. The crew could bail out. All 10 men could survive. land in Romanian territory, become prisoners of war, but alive. Baker assessed their situation. The mission was complete. The 93rd had destroyed their assigned targets. Bombs had devastated the Astro Romana refinery.

The other bombers were escaping. Some would make it back to Libya. Some wouldn’t. But the attack had succeeded. Germany’s fuel supply was crippled. The cost had been enormous. At least four aircraft lost, probably more. Hell’s Wench was finished. No possibility of reaching friendly territory. The smart decision was immediate bailout. Save the crew. But Baker knew the statistics.

Bailing out over Romania meant capture, interrogation, prison camp, years of captivity. Some crew members wouldn’t survive that. The harsh conditions, disease, malnutrition, and if Germany lost the war, which seemed increasingly likely, some prisoners might never make it home. Executions happened. Massacres. The SS had killed prisoners before. Could happen again.

Baker made another calculation. Hell’s Wench still flew. Damaged, burning, dying, but flying. If he could gain more altitude, the crew could bail out over Yugoslavia, partisan territory. Friendly forces operated there, rescued downed airmen, smuggled them back to Allied lines. Higher altitude meant longer glide distance after the engines failed.

Better chance of reaching partisan zones, but gaining altitude meant staying in the burning aircraft longer. The fire was spreading. Time was running out. Baker pulled back on the yolk. Hell’s wench climbed slowly. 900 ft, 1,000 ft, 1,200 ft. Every 100 ft of altitude bought the crew better survival odds, but the climb cost time. time the burning aircraft didn’t have.

The fire had now consumed half the fuselage. Flames burned through electrical systems. Radio went dead. Intercom failed. Baker could no longer communicate with the crew. Couldn’t order bailout. Couldn’t coordinate evacuation. Each man would have to make his own decision.

The engineer, James Merritt, stood in the cockpit doorway, watched Baker and Jerstad fight the controls, saw the flames spreading toward the cockpit, felt the heat radiating through the metal walls. He understood what Baker was attempting, gain altitude, give everyone better chance. Merritt returned to his station, didn’t bail out, stated his post, monitored the dying engines, adjusted fuel mixture, transferred fuel from damaged tanks to functioning ones, bought them precious minutes. Behind merit, the four gunners remained at their positions. Top turret gunner

tracked the sky for enemy fighters. Waist gunners watched for pursuing measure smmiths. Tail gunner scanned their six:00 position. No fighters appeared. The Luftvafa had pulled back. German commanders knew Hell’s Wench was finished. No need to waste ammunition. The burning bomber would crash on its own. The gunners could see the ground through gaps in the smoke.

Romanian countryside, fields, villages, enemy territory. They stayed at their stations. 1,500 ft. The aircraft shuttered violently. Number four engine seized completely. The propeller windmilled, created massive drag. Baker compensated with rudder. The aircraft yawed right. He fought it level. Three engines remained. Number one running on failing oil pressure. Number two still good.

Number three restarted after cooling briefly, but the restart wouldn’t last. The engine was damaged, running rough, producing minimal power. The right wing was structurally failing. The fire had burned through primary spars. Loadbearing members. The wing bent upward under aerodynamic stress. Metal groaned. Rivets popped like gunshots. The wing was folding.

When it failed completely, the aircraft would roll inverted, spin into the ground. No time for bailout. Everyone would die in the crash. Baker needed altitude before that happened. Needed to get high enough that when the wing failed, the crew could escape the tumbling aircraft. 1,700 ft. They were 15 mi south of Peshi now, still over Romania, still enemy territory, but closer to Yugoslavia. The partisan zones were 40 mi ahead.

If they could maintain altitude for another 10 minutes, they’d reach friendly territory. The crew could bail out safely, get rescued, return to fight another day. Baker pushed the aircraft harder, demanded performance it couldn’t give. The remaining engine screamed, overheated, began failing. Number one engine caught fire.

Different fire from the wing blaze. This one burned inside than the cell. Engine oil ignited. Flames shot from the cowling. The fire spread to number two engine. The only engine still producing full power. Baker watched his last good engine start to burn. He had maybe 90 seconds before complete power loss.

90 seconds to gain every possible foot of altitude. He kept climbing. Bombardier McCormick lay in the nose, watched the ground pass beneath, calculated their trajectory. Air speed dropping, altitude increasing slowly, rate of climb decreasing, the mathematics were clear. They wouldn’t make Yugoslavia. The engines would fail before they crossed the border.

The aircraft would crash in Romania. But McCormick didn’t move toward the escape hatch, didn’t prepare to bail out. He stayed at his station. Trusted Baker’s judgment. 1900 ft. Number two engine died. Just stopped. No explosion. No dramatic failure. The engine simply quit. Starved of oil. Seized from heat. Gone.

Now Hell’s Wench flew on two damaged engines. Number three running rough. Number one burning. The aircraft couldn’t maintain altitude anymore. Started descending 100 ft per minute. then 200. The descent accelerated. Baker had run out of options. The crew had maybe 60 seconds to bail out before the aircraft became uncontrollable.

He needed to give the order, but the intercom was dead. He couldn’t tell them to jump. And the right wing chose that moment to fail. The right wing separated at the route. The entire structure tore away from the fuselage. 28 ft of wing, two engines, fuel tanks, all gone in one catastrophic failure. The sudden loss of lift on one side rolled Hell’s Wench violently. The aircraft snap rolled left, inverted in 2 seconds.

The centrifugal force pinned everyone against the walls, made movement impossible. Escape hatches were now above the crew. Gravity worked against them. No one could reach the exits. Baker fought the controls uselessly. With one wing gone, aerodynamic forces overwhelmed any control input. The rudder had no effect. Ailerons couldn’t counter the roll. The aircraft was tumbling.

Spinning toward the ground in an uncontrollable descent. Through the windscreen, Baker saw Earth and sky alternating rapidly. The horizon spun. The altimeter unwound. 1,800 ft 1,600,400 descending at 3,000 ft per minute. The crew knew what was happening, felt the violent roll, understood the wing had failed. Merritt grabbed for hand holds, couldn’t reach them. The centrifugal force threw him against the bulkhead.

The gunners tumbled through the fuselage, slammed into equipment, into each other, into the burning walls. McCormick in the nose watched the ground rush upward. Calculated impact in 28 seconds. He didn’t scream, didn’t panic, just watched. Gerstad remained strapped in the co-pilot seat. The harness held him secure despite the violent rotation.

He looked at Baker. Both men knew this was the end. No bailout possible, no emergency landing, no survival. The aircraft was a spinning coffin. They’d completed the mission, led the 93rd to the target, destroyed the refinery, kept flying when they could have landed safely, made the choice. This was the consequence.

1,00 ft. The spin accelerated. Aerodynamic forces increased as air speed built. The aircraft rotated faster. Four revolutions per second. The remaining left wing began failing under the stress. Metal screamed. The fire spread throughout the fuselage. Consumed everything. The ammunition for the 50 caliber guns began cooking off. Rounds exploded randomly. Sent bullets ricocheting through the interior.

added chaos to the catastrophe. The ground details became visible. Trees, a road, farm buildings, Romanian farmers working fields. They looked up, saw the burning bomber spinning downward, black smoke trailing behind it in a corkcrew pattern. The sound was immense. Screaming engines, rushing wind, exploding ammunition.

The farmers ran, scattered away from the impact point, knew what was coming. 600 ft. Hell’s wench completed its final rotation. The nose pointed almost straight down. The remaining engine still ran, still pushed the aircraft faster toward the ground. Baker saw the impact point, a field, bare earth. The aircraft would hit at over 300 mph.

The impact would be instantaneous. No pain, no drawn out death, just sudden ending. 300 ft. Jerstad reached across the cockpit, gripped Baker’s shoulder. A final gesture, acknowledgement. They’d flown together, made the hard choice together, would die together. Baker nodded once, kept his hands on the controls, died doing his job. Pilot to the end.

Hell’s wench struck the Earth at 9:47 a.m. Romania time. 3,000 lb of remaining fuel detonated on impact. The explosion created a crater 15 ft deep and 40 ft across. Debris scattered across 200 yards. The aircraft disintegrated completely. All 10 crew members died instantly.

Lieutenant Colonel Addison Baker, Major John Gerstad, Navigator Harold Sweetman, Bombardier John McCormack, Engineer James Merritt, radio operator Cecil Fight, four gunners whose bodies were identified by dog tags recovered from the wreckage, the volunteer who didn’t have to fly, the commander who led from the front, and eight men who followed them into hell. Gone. Romanian authorities arrived within the hour, recovered what remained.

10 Americans who’d flown 1500 miles to destroy oil refineries, who’d succeeded, who’d paid the ultimate price. The bodies were buried in a local cemetery, the graves marked with wooden crosses. The war continued without them, but their mission had changed everything. Operation Title Wave concluded at 10:32 a.m. on August 1st, 1943.

178 B24 Liberators had departed Benghazi that morning. 125 returned, 53 aircraft lost, 310 airmen killed, 54 captured, 108 wounded. The single costliest air mission in American military history to that point. The losses exceeded even the worst predictions. Command had estimated 50% casualties. The actual figure reached 30% for aircraft, but among the crews that pressed their attacks to the target, losses approached 60%.

The 93rd bomb group paid the heaviest price. Addison Baker led 18 bombers toward Pesti after breaking formation. Only 11 returned to Libya, seven aircraft lost, 70 men dead or missing. But those 18 bombers had destroyed their assigned targets completely. The Astro Romana refinery was knocked offline for 3 months. The UniAria facility remained closed for 6 months.

Delayed fuse bombs had penetrated deep into critical equipment. Cracking towers collapsed, pipeline networks ruptured, storage tanks burned for days. German engineers surveyed the damage and reported complete reconstruction would take years. Across Pesti, the other bomb groups achieved similar results. The refineries that supplied 1/3 of Nazi Germany’s fuel were crippled.

Daily production dropped from 12 million barrels annually to less than 4 million. The shortfall created immediate problems for German operations. Luftwafa sorty rates decreased. Panzer divisions received reduced fuel allocations. Ubot spent less time on patrol. The strategic impact rippled throughout the Vermacht.

Some historians estimate Operation Tidal Wave shortened the war in Europe by 3 months. But the cost haunted military planners. 53 aircraft, 310 men. The mathematics were brutal. Command evaluated whether the results justified the losses, whether destroying oil refineries was worth the price in American lives. The debate continued throughout the war. No clear answer emerged. The oil was crucial. The losses were catastrophic.

Both facts remained true. The Medal of Honor citations arrived 6 months later. Five men received America’s highest military decoration for actions during operation title wave. More medals of honor than any other single air operation in history. Lieutenant Colonel Addison Baker received his postumously. The citation read that he flew his burning aircraft to the target despite having opportunity to land safely, led his group through the heaviest defenses in Europe, completed the mission at cost of his life and the lives of his crew.

Major John Gerstad received a Medal of Honor postumously as well. The citation noted he volunteered for the mission after completing his required tour. Served as Baker’s co-pilot, remained at his post in the burning aircraft, made the choice to continue when survival was possible, died completing the mission.

He was 25 years old, had finished his war, could have gone home to Oregon. Instead, flew one more mission. Never returned. The other eight crew members of Hell’s Wench received no individual medals. Their names appeared in casualty lists. Harold Sweetman, John McCormack, James Merritt, Cecil Fight.

Four gunners whose families received telegrams explaining their sons had died in action over Romania. Standard wartime notifications. Nothing that captured what they’d done. nothing that explained they’d flown a burning bomber through the worst defenses in Europe because their commanders asked them to.

If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor, hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about pilots who chose the mission over survival. Real people, real sacrifice. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from.

Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer. You’re part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching. And thank you for making sure Lieutenant Colonel Addison Baker and Major John Gerstead don’t disappear into silence.

These men deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that happen.

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load