August 14th, 1944. 0930 hours mountain pass near Monte Casino, Italy. The modified jeep screamed up the 15° grade at 47 mph, carrying three wounded soldiers and a battalion surgeon who’d been caught behind German lines during a failed patrol. Standard jeeps struggled to reach 20 mph on this slope, loaded or unloaded.

But technical Sergeant Frank Frankie Castayano’s Jeep, powered by an engine that every officer and mechanic in the motorpool had mocked for three months, was achieving speeds that shouldn’t have been possible. Through the windshield, Castayano could see German machine gun positions approximately 800 yd ahead, positioned to interdict the only road connecting Allied positions to the forward aid station.

Those guns had destroyed two ambulances and disabled three jeeps in the past 48 hours. Every vehicle attempting this run moved at crawling speeds due to the grade, making them perfect targets for German gunners who had ranged every inch of the road. But Castayano’s engine, cobbled together from salvaged parts, improvised modifications, and engineering that formerly trained mechanics had declared impossible, was producing approximately 200 horsepower from components designed for 60.

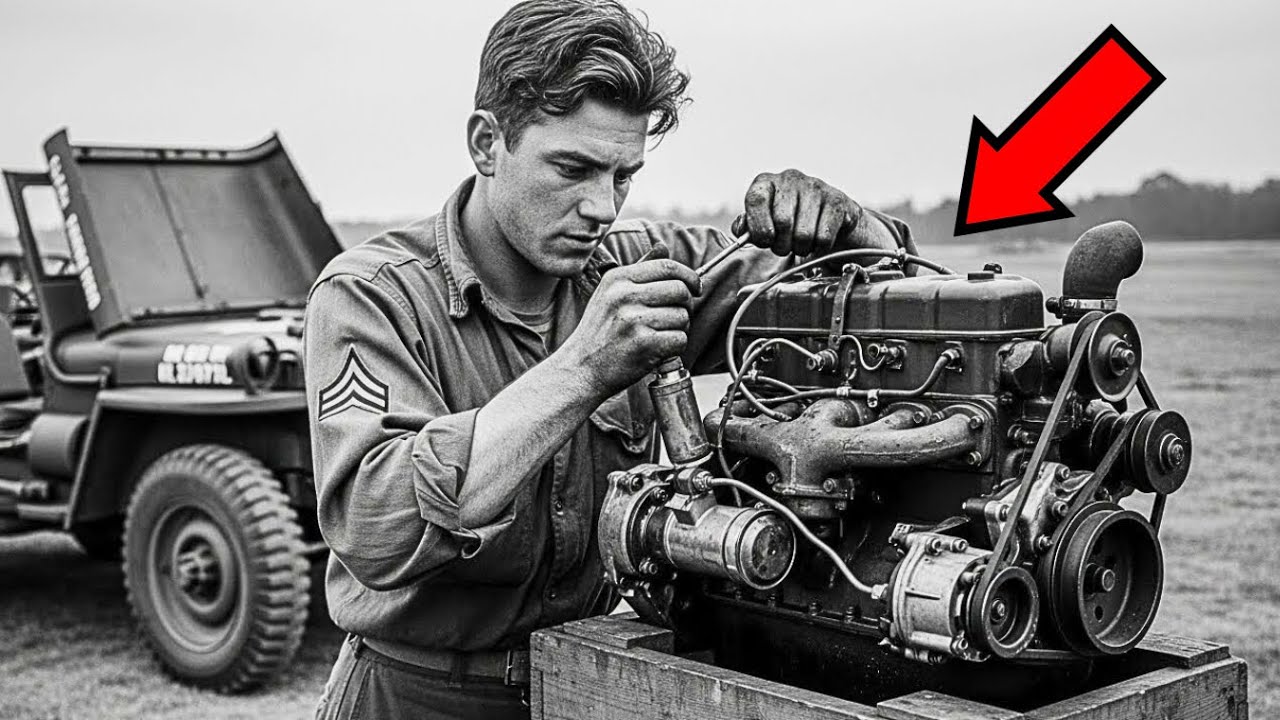

The GoDevil four-cylinder engine, standard equipment in every Willys MB Jeep, had been transformed through modifications that violated every Army technical manual and manufacturer specification. The acceleration was brutal. The surgeon, Captain Robert Morrison, braced himself against the dashboard as the Jeep’s speed increased to 53 mph.

This is insane, Morrison shouted over the engine’s roar. Jeeps don’t go this fast. Castiano, hands locked on the steering wheel as the vehicle vibrated with power it was never designed to handle, grinned. This one does, sir. Hold on. At 0932, German machine guns opened fire. Tracer rounds arked toward the jeep, aimed where standard vehicles would have been if they’d started from the same position seconds earlier.

But Castellaniano’s engine had carried them 200 yards beyond predicted position. The bullets struck empty road behind them. Costano pushed the throttle to maximum. The modified engine screaming at RPMs that should have destroyed it. Responded with more power. 60 mph on a 15° grade loaded with five men and medical supplies.

The engineering was impossible. The mathematics didn’t work. But the Jeep, powered by engine that had been mocked as garage scrap, welded together by amateur, was outrunning machine gun fire through performance that no factory-built vehicle could match. They reached the aid station at 0934, having covered 3 mi of mountain road under fire in 4 minutes.

Captain Morrison climbed out on shaking legs, turned to Castiano, and said the words that would transform mockery into legend. I don’t know what you built into that engine, but it just saved five lives, including mine. Whatever they’ve been saying about your homemade modifications, they’re wrong. This is the fastest, most powerful Jeep I’ve ever seen.

The journey to this Italian mountain pass and the engine that shouldn’t exist began 28 years earlier in Brooklyn, New York. Frank Castayaniano was born in 1916 to Italian immigrant parents who operated a small automotive repair shop in a workingclass neighborhood. His father, Joseph Castelliano, was self-taught mechanic who’d learned his trade through necessity.

Maintaining vehicles for customers who couldn’t afford dealership prices. Growing up in depression era Brooklyn meant understanding that survival required making old things work better. Young Frank spent his childhood in his father’s garage watching repairs, learning improvisation, understanding that engineering books described ideal conditions while real mechanics dealt with broken reality.

By age 12, Frank could rebuild carburetors. By 15, he was modifying engines to extract performance that manufacturers claimed was impossible. The Castellano approach to mechanics was fundamentally different from formal engineering. Jeppe taught his son that manufacturer specifications were conservative estimates designed for liability protection, not actual performance limits.

Every engine could produce more power if you understood its true constraints rather than published ones. Every vehicle could perform better if you stopped accepting manufacturer limits and started exploring actual possibilities. By age 18, Frank had built local reputation as the Brooklyn kid who could make anything go faster.

He modified delivery trucks to carry more load, souped up taxi engines to consume less fuel, rebuilt police vehicles to achieve speeds the department didn’t know were possible. His modifications violated every manufacturer warranty and technical specification. They also worked better than factory equipment. Joseeppe’s lesson was simple.

Engineers design for average conditions. Lawyers set conservative limits. Manufacturers prioritize cost over performance. But if you understand what components actually can handle ratherthan what paperwork says they should handle, you can build things that shouldn’t exist but work better than things that should.

Frank Castiano was drafted in January 1942, weeks after Pearl Harbor. His induction papers listed his occupation as automotive mechanic, which made him valuable asset for army motor transport. He was assigned a motor pool duty after basic training, maintaining the vehicles that kept armies mobile. The assignment should have been routine.

Army vehicles were designed for durability and ease of maintenance, not performance. Jeeps, trucks, halftracks, all were engineered for reliability under harsh conditions with minimal skilled maintenance. Performance was secondary to survival. Frank’s modification instincts honed making Brooklyn vehicles go faster seemed irrelevant to military requirements.

But Frank saw opportunity where others saw limitations. Army vehicles were overengineered for durability, meaning they had safety margins that could be exploited for performance. The GoDevil engine in Willy’s Jeeps was rated at 60 horsepower, but that rating was conservative estimate. The actual components could handle significantly more stress if properly modified.

Frank began experimenting. Small modifications at first, nothing that would attract attention. carburetor adjustments that increased fuel flow, timing changes that optimized combustion, port polishing that reduced internal friction. Each modification extracted slightly more performance while maintaining reliability.

The improvements were modest, perhaps 5 to 8 horsepower gains, but they demonstrated that factory specifications were starting points rather than absolute limits. By summer 1942, Frank’s modifications had attracted notice from motorpool sergeants who recognized that his vehicles performed better than standard equipment.

Master Sergeant Harold Wilson, motorpool commander at Fort Benning, Georgia, pulled Frank aside after one particularly impressive demonstration. You’ve made this Jeep faster than it should be. How? Frank shrugged. Factory specs are conservative. If you understand what the parts can actually handle and optimize everything, you can get more power.

Sergeant Wilson considered this. Can you do it without breaking things? Frank nodded. If done right, modifications improve reliability by reducing strain on components operating below optimized performance. Wilson made decision. You’re now assigned to vehicle modification duties. Make our equipment better.

just don’t break anything expensive. This authorization, informal and unauthorized by higher command, gave Frank freedom to experiment. He began systematic modification program, documenting what worked and what failed. He learned through trial and error that army vehicles had enormous untapped potential if you were willing to void warranties and ignore technical manuals.

Frank deployed to North Africa in November 1942 with Motor Transport Company supporting Operation Torch. The harsh desert environment tested vehicles beyond design specifications. Sand infiltrated everything. Heat stressed engines. Rough terrain broke suspensions. Standard vehicles failed regularly.

Frank’s modified vehicles kept running. The North Africa experience taught Frank critical lessons about military vehicle requirements. Performance mattered less than reliability under extreme conditions. Modifications that increased power but decreased durability were worthless. But modifications that increased power while maintaining or improving durability were invaluable.

The challenge was finding the engineering balance that factory specifications ignored because they optimized for different priorities. By summer 1943, Frank had developed comprehensive understanding of GoDevil engine’s true capabilities. The four-cylinder engine, designed conservatively for 60 horsepower at 4,000 RPM, could produce significantly more if properly modified.

The cylinder head could handle higher compression. The crankshaft could tolerate higher RPMs. The cooling system could dissipate more heat. Each component had safety margins that could be exploited. The Italian campaign beginning September 1943 brought new challenges. Mountain warfare required vehicles capable of steep climbs while carrying heavy loads.

Standard Jeeps struggled on grades exceeding 10°. Fully loaded jeeps often couldn’t climb at all, requiring towing or partial unloading. This limitation created tactical problems when rapid movement through mountainous terrain was essential. Frank proposed solution that his superiors considered absurd. Completely rebuild Goevil engine with modifications that would triple its power output.

Use salvaged parts from destroyed vehicles. improvised components fabricated in field workshops and engineering techniques that violated every Army technical manual. Create engine that produced 200 horsepower from components designed for 60. The response was immediate mockery. Battalion motor officer Captain James Hendersonliterally laughed.

Sergeant, that’s impossible. You can’t triple an engine’s power output with salvaged parts and field modifications. The engineering doesn’t work. You’d destroy the engine in minutes, Frank responded calmly. Sir, with respect, factory engineering optimizes for cost and liability if you optimize for performance and understand true component limits.

You can achieve outputs that conservative specifications say are impossible. Henderson shook his head. I’m not authorizing you to waste parts and time on fantasy project. maintain vehicles per technical manual specifications, no modifications without written authorization. But Master Sergeant Wilson, who’d transferred to Italy with Frank’s unit, remembered Fort Benning demonstrations.

He authorized Frank to use salvage parts from destroyed vehicles for experimental purposes. Don’t ask for new parts. Don’t disrupt regular maintenance. Work on your own time. But if you can actually build 200 horsepower Jeep engine from scrap, I want to see it. Frank began the project in April 1944, working nights and during offduty hours.

The base was a wrecked Jeep engine salvaged from a vehicle destroyed by German artillery. The modifications were comprehensive and radical. First, the cylinder head. Frank machined the combustion chambers to increase compression ratio from 6.5 to one up to 9:1. Higher compression meant more power but required stronger components to handle increased stress.

He reinforced weak points using steel plate from destroyed German vehicles welding and machining reinforcements that manufacturer never intended. Second, the carburetor. The standard Carter WO carburetor was designed for fuel efficiency, not maximum power. Frank rebuilt it using larger jets from destroyed truck engines, modified throttle bodies, and custom ventury dimensions calculated through trial and error.

The result was carburetor that could deliver three times standard fuel flow when needed. Third, the ignition system. Standard distributor and coil were designed for reliable starting and fuel efficiency. Frank rebuilt them for maximum spark energy at high RPMs using components from various sources welded together into hybrid system that technical manuals would have classified as unsafe.

Fourth, the cooling system. Tripled power output meant tripled heat generation. Frank fabricated larger radiator using components from destroyed vehicles, improved water pump using modified truck parts, and enhanced air flow through hood modifications that looked crude but improved thermal management dramatically.

Fifth, the exhaust system. Standard restrictive mufflers reduced power through excessive back pressure. Frank fabricated free flowing exhaust using salvaged pipe, eliminating restrictions that choked engine performance. The result was loud but efficient. Sixth, the crankshaft and connecting rods. These required no modification since they were already overengineered for standard power output.

But Frank carefully balanced the rotating assembly to reduce vibration at high RPMs. The work took 3 months. Every component was salvaged, fabricated, or improvised. Nothing came from supply channels. The entire engine was built from parts that army regulations classified as salvage or scrap. The mockery from other mechanics was constant and cruel.

They called it Frankenstein’s motor, the monster built from dead parts. They predicted catastrophic failure within minutes of operation. They joked that Frank was wasting time that could be spent on actual maintenance. They suggested his Brooklyn background meant he didn’t understand real engineering. The mockery was relentless.

But Frank continued working. He understood something the mockers didn’t. Conservative engineering specifications exist for legal and economic reasons, not because components can’t handle more stress. Every part has safety margin. Every system has untapped potential. The question isn’t whether you can exceed specifications. The question is whether you understand true limits well enough to exceed them safely.

In July 1944, Frank completed the engine and installed it in a Jeep that had been scheduled for salvage after frame damage. He’d repaired the frame using welded reinforcements, another improvisation that technical manuals said was impossible. The complete vehicle was mockery magnet salvage jeep with impossible engine built from scrap parts by amateur who thought he knew better than engineers.

The first test came at 0600 hours on July 18th, 1944. Frank started the engine. It fired immediately, settled into rough idle that smoothed as fuel mixture optimized. He let it warm up for 5 minutes, checking for leaks, listening for abnormal sounds, monitoring oil pressure and temperature. Everything looked good.

Then he eased the throttle forward. The Jeep accelerated with force that surprised even Frank. The power was immediate and overwhelming. Standard Jeeps took 5 to 6 seconds to reach 25 mph.Frank’s Jeep hit 25 in under 3 seconds. At 15 seconds, it had reached 45 mph on flat ground. Top speed on test track 67 mph.

More than double standard Jeep’s 30 mph maximum. Master Sergeant Wilson witnessed the test. Holy hell, Castiano, you actually did it. That thing moves like sports car. How much power? Frank had calculated approximate output based on performance around 190 to 210 horsepower, Sergeant. Maybe more. I won’t know exactly without dynamometer testing, but acceleration and top speed suggest we’re in that range.

Wilson nodded slowly. This needs to go up the chain. They need to see this. But within the battalion, word spread rapidly about the impossible engine that actually worked. The mockery began shifting toward grudging respect, though many remained skeptical until they witnessed performance personally. Captain Henderson remained dismissive.

Fast on test track doesn’t mean useful in combat. Jeeps aren’t race cars. They’re utility vehicles. That engine will fail under stress. Mark my words, Sergeant Castayano’s garage special will break down at the worst possible moment. The combat test came two weeks later. The August 14th medical evacuation run up the Monte Casino pass described at the opening provided perfect demonstration of the engine’s tactical value.

Out running machine gun fire through speed that shouldn’t exist, completing mission that two ambulances and three standard jeeps had failed attempting, saving five lives, including battalion surgeon. The performance was undeniable. If you’re fascinated by the improvised engineering and mechanical ingenuity that gave Allied forces unexpected advantages in World War II, make sure to subscribe to our channel and hit the notification bell.

We bring you the untold stories of the soldiers who achieved extraordinary results through innovation under impossible conditions. Don’t miss our upcoming videos on the modifications that changed combat outcomes. The August 14th success transformed the modified Jeep from mockery to legend overnight. Within 48 hours, Battalion Commander Lieutenant Colonel Robert Mansfield personally inspected the vehicle and authorized its continued combat use.

More significantly, he ordered Motorpool to document Frank’s modifications for potential replication. But replication proved impossible for most mechanics. The modifications required understanding that went beyond following instructions. Frank had built the engine through feel, intuition, and trial and error process that couldn’t be reduced to written procedures.

Other mechanics who tried to copy his work produced engines that either failed immediately or provided minimal performance improvement. The fundamental challenge was that Frank’s modifications weren’t standardized. He’d adapted each component based on what salvaged parts were available, what worked in testing, and what his intuition suggested would work.

The result was one-of-a-kind engine that couldn’t be mass-roduced because it had never been formally designed. It had been evolved through iterative experimentation. Between August and December 1944, Frank’s Jeep performed missions that standard vehicles couldn’t attempt. Medical evacuations under fire, ammunition resupply to forward positions, courier runs through contested territory, reconnaissance missions requiring speed to escape contact.

Each mission demonstrated tactical value that performance specifications couldn’t capture. The October 7th mission typified the jeep’s capabilities. German forces had cut off a forward observation post, trapping three artillery spotters with critical intelligence about German tank positions. Standard relief force would take hours to fight through German positions.

Frank volunteered to attempt speedrun that might extract the spotters before Germans overran their position. The route was 12 mi through partially contested territory, including 2 miles directly exposed to German observation. Standard jeeps needed 45 minutes for this route under good conditions. Frank completed it in 19 minutes, achieving speeds approaching 70 mph on straightaways and maintaining 30 plus mph on rough terrain where standard jeeps struggled to reach 15.

The extraction succeeded. Three spotters recovered with intelligence that enabled devastating artillery strike against German armor. The mission report noted, “Technical Sergeant Castayano’s modified vehicle provided capability that enabled mission success that would have been impossible with standard equipment.

The vehicle’s extraordinary performance under combat conditions validates experimental modifications despite technical manual violations. But success brought new problems. Other units heard about the 200 horsepower Jeep and requested similar vehicles. Motor transport command wanted Frank to document modifications for wider implementation.

Engineering officers wanted technical specifications that didn’t exist because Frank had never created formal documentation.Frank’s attempt to explain his modifications to engineering officers revealed the disconnect between formal engineering and practical improvisation. You increased compression ratio to 9:1. One engineer noted.

That requires higher octane fuel than army supplies. How are you preventing detonation? Frank shrugged. I advanced timing slightly. Enriched mixture at high load and the engine just handles it. I don’t know why it doesn’t detonate. It just doesn’t. The engineer was frustrated. That’s not engineering. That’s guesswork. Frank responded calmly.

Sir, with respect, formal engineering optimizes designs before building. Field engineering builds tests and optimizes through iteration. Your approach is better for mass production. Mine is better for one-off solutions to immediate problems. Both are engineering, just different methodologies. This philosophical difference between formal design engineering and iterative field engineering explained why Frank’s modifications couldn’t be easily replicated.

He’d built through experimentation, kept what worked, discarded what failed, and never documented the process because each engine required unique adaptations based on available parts. December 1944 brought the ultimate test. The German Arden’s offensive created desperate situations requiring maximum vehicle performance. Frank’s unit was rushed north to Belgium as part of reinforcements responding to the breakthrough.

The modified Jeep’s performance in winter conditions where standard vehicles struggled even without combat stress would determine whether the modifications were tactical advantage or dangerous liability. The December weather was catastrophic. Freezing temperatures, snow, ice, conditions that destroyed standard vehicles performance, cold weather starting, frozen fuel lines, lubricant thickening, all degraded vehicle capability.

Standard Jeeps that managed 30 mph in summer struggled to reach 20 in December conditions. Frank’s engine, designed without consideration for cold weather operations, should have failed completely. But improvisation that had characterized the build now characterized its maintenance. Frank modified fuel mixture for winter conditions, changed lubricants to reduce cold weather viscosity, added improvised engine heating that maintained operating temperature even in subfreezing conditions. The result was vehicle that

performed better in winter than standard Jeeps performed in summer. While other vehicles struggled with cold weather, Frank’s modifications had inadvertently created engine that ran efficiently in extreme cold. The high compression ratio actually improved cold starting. The modified cooling system prevented over cooling.

The whole package designed for Italian summer conditions worked better in Belgian winter. Between December 18th and December 31st, Frank’s Jeep performed 23 combat missions during the Arden fighting, ammunition resupply under fire, casualty evacuation, messenger runs between cutoff units, reconnaissance missions.

The modified engine’s combination of speed and reliability under extreme conditions made it invaluable asset. The December 24th mission demonstrated both the engine’s capability and its limitations. Frank was tasked with evacuating wounded from surrounded position at Bastonia. The route required crossing German-h held territory at night in fog through snowcovered roads.

Standard vehicles couldn’t attempt this mission due to speed and reliability concerns. Frank completed the run, extracted six wounded soldiers, and returned through German positions that never realized American vehicle had passed through their lines. The speed and reliability that everyone had mocked enabled mission impossible for conventional vehicles, but the stress was showing.

The engine, which had operated continuously since July, with only field maintenance, was developing issues. Oil consumption increased. Strange noises appeared at high RPM. Power output, while still far exceeding standard specifications, had decreased from peak performance. The engine that had achieved 200 plus horsepower in August, was probably producing 170 to 180 horsepower by December.

Still triple standard output, but declining. Master Sergeant Wilson pulled Frank aside on December 28th. Your engine is wearing out. I can hear it. You’ve pushed it too hard for too long. Frank nodded. I know, Sergeant. It’s been running continuous high-stress operations for 5 months. Standard engines are rebuilt every 8,000 m under normal conditions.

I’ve probably put 15,000 hard miles on this engine with minimal maintenance. It’s amazing. It’s still running at all. Wilson asked the critical question. Can you rebuild it? Frank considered carefully. If I had parts, yes. But I built this engine from specific salvaged components that aren’t available now.

I could build another engine with similar modifications if I had time and parts, but I can’t replicate this specific engine because I don’t remember every modification Imade. It evolved organically. I adapted as I went. There are probably 50 small modifications I made during initial build that I can’t remember specifically. This admission revealed the fundamental limitation of Frank’s approach.

The engine was unreplicable because it had never been systematically designed. It had been iteratively developed through process that couldn’t be documented after the fact. The knowledge existed in Frank’s hands and intuition, not in written specifications that could be transferred to others. January 1945 brought the engine’s retirement.

On January 7th, while conducting routine supply run, the engine experienced catastrophic failure. A connecting rod stressed beyond its design limits for 6 months fractured at high RPM. The failure was sudden and complete. The engine that had achieved impossible performance for half a year destroyed itself in seconds. Frank examined the wreckage with satisfaction rather than disappointment.

6 months of continuous hard operation, producing triple standard power under combat conditions that would have destroyed most engines in weeks. And it died doing exactly what it was designed to do, going faster than any Jeep should go. That’s not failure. That’s success taken to its absolute limit. The Army’s analysis of the engine revealed modifications that engineers found simultaneously impressive and horrifying.

The postfailure technical report noted subject engine demonstrates that goevil design has significant performance potential beyond factory specifications. modifications achieved approximately 3.3 times standard power output and sustained this performance for estimated 15,000 miles under severe operating conditions.

However, modifications violate multiple safety specifications, require extensive custom fabrication, depend on salvaged parts of uncertain origin, and cannot be standardized for mass production. connecting rod failure. The destroyed engine was predictable result of sustained overstress. That engine operated approximately four times longer than conservative analysis would predict before failure.

Assessment technical Sergeant Castano’s modifications demonstrate possibility of field expedient performance enhancement but are unsuitable for systematic implementation. The engineering approach while effective in specific case cannot be replicated without similar expertise and trial and error development. Recommend documentation of general principles for training purposes while acknowledging that specific implementation cannot be standardized.

This assessment captured both the value and limitation of Frank’s work. He’d proven that significant performance enhancement was possible through field modification, but the achievement wasn’t transferable because it depended on his unique combination of knowledge, intuition, and willingness to experiment. Before we continue with the post-war legacy and lasting impact of this remarkable engineering achievement, I want to ask you to take just two seconds to subscribe to our channel if you haven’t already. These deep dives into

the mechanical innovations and improvised engineering that shaped combat outcomes take enormous research effort. Your subscription helps us continue bringing these untold stories to light. Hit that subscribe button and the notification bell. Frank spent the rest of the war performing conventional motor pool duties.

He maintained standard vehicles per technical manual specifications, trained mechanics in proper procedures, and avoided unauthorized modifications. The experimental phase was over, but his reputation as the sergeant who’ built Impossible Engine remained throughout the motor transport community. Other mechanics who had mocked the project in April 1944 now sought Frank’s advice on their own modification ideas, but Frank discouraged most of them.

What I did worked because I understood the specific components I was modifying and I tested everything thoroughly. You can’t just copy modifications without understanding why they work. That’s how you get catastrophic failures instead of performance improvements. This wisdom, recognizing that successful modification requires deep understanding rather than simple replication, was perhaps Frank’s most important contribution.

Engineering isn’t following instructions. It’s understanding principles deeply enough to adapt them to specific situations. Frank mustered out in December 1945, returned to Brooklyn, and rejoined his father’s garage. But war experience had transformed his approach to automotive work. He now understood that performance modification required systematic testing and careful documentation, not just intuitive experimentation.

The garage evolved from general repair shop into performance modification specialist. In 1947, Frank opened his own shop specializing in custom engine modifications. The shop’s reputation grew throughout the 50s and 60s as Frank applied lessons learned building the impossible Jeepengine to civilian vehicles.

He modified taxi engines for better fuel economy, police vehicles for higher performance, and private cars for enthusiasts who wanted more power. But Frank remained humble about his wartime achievement. In a 1968 interview for Automotive magazine, he reflected on the 200 horsepower Jeep engine and what it represented. I didn’t invent anything.

I just recognized that factory specifications are conservative and that properly modified equipment can exceed those specifications. Thousands of mechanics could have done what I did. I just happened to be the one willing to try. The interviewer asked if Frank was proud of building engine that tripled standard power output.

The response was characteristically modest. Proud? Not really. Satisfied that I solved problem that needed solving. The military needed vehicles capable of high performance in mountainous terrain under combat conditions. Standard equipment couldn’t do that. So, I built equipment that could. That’s what mechanics do. They solve problems.

This perspective, viewing extraordinary achievement as ordinary problemolving, characterized Frank’s entire relationship with his accomplishments. He never claimed to be exceptional engineer. He simply claimed to be competent mechanic who’ recognized that conventional limits weren’t actual limits.

The engineering principles Frank demonstrated influenced post-war military vehicle development. The recognition that standard specifications could be significantly exceeded under certain conditions led to development of vehicles with greater power reserves and more robust designs that could accommodate field modifications when necessary.

Modern military logistics includes planning for field modification and improvised solutions. The assumption that vehicles will be used exactly as designed has been replaced with recognition that combat conditions require adaptation. Frank’s homemade engine, which should have been impossible, proved that sometimes impossible means hasn’t been tried yet rather than actually impossible.

The specific engine that Frank built was never preserved. After catastrophic failure in January 1945, it was salvaged for parts like any other destroyed engine. No photographs exist of the engine in detail. The only documentation is the technical report filed after failure and Frank’s later recollections which were imprecise about specific modifications.

But the legend of the 200 horsepower Jeep engine persisted in military motor transport community for decades. The story became teaching example in army mechanic schools, illustrating both the potential for field modification and the importance of understanding engineering principles rather than just following procedures.

Frank Castayano died in 1998 at age 82 in Brooklyn. His obituary mentioned his army service but focused on his 50-year career as automotive performance specialist. His custom shop, still operating under his son’s management, had become institution among New York automotive enthusiasts. Among Frank’s papers, family discovered a notebook from 1944 containing rough sketches and notes about the Jeep engine modifications.

The notes weren’t comprehensive engineering documentation, just memory aids and calculation scribbles, but they provided window into Frank’s thought process during the build. One note dated May 20th, 1944 captured Frank’s philosophy. Factory specs exist for mass production and liability reasons. They optimize for cost, reliability under average conditions, and legal protection.

But actual components can handle much more stress if you understand their true limits and accept that increased performance means increased maintenance and shorter lifespan. The question isn’t whether you can exceed specs. The question is whether exceeding them provides value that justifies the trade-offs.

This note written while other mechanics were mocking his project revealed that Frank understood exactly what he was attempting and what the limitations would be. The engine that produced 200 horsepower was never meant to last forever. It was meant to provide maximum performance for as long as necessary, accepting that increased performance meant decreased lifespan.

Modern performance engineering explicitly recognizes this trade-off. Race engines produce enormous power but require complete rebuilds after hours of operation. Stock engines produce modest power but run reliably for hundreds of thousands of miles. The engineering challenge is matching performance and durability to requirements.

Frank understood this instinctively in 1944, decades before it became standard engineering philosophy. The mathematical analysis of what Frank achieved is striking. Standard goevil engine 60 horsepower 4,000 RPM maximum designed for 100,000 mi durability. Frank’s modified engine, approximately 200 horsepower, 7,000 RPM maximum, 15,000 miles actual durability before catastrophic failure.

The power increase of 3.3 times came with durabilitydecreased to 15% of standard design. But under wartime conditions where immediate performance mattered more than long-term durability, this was optimal trade-off. Standard engines that would have lasted 8 years in civilian use but couldn’t complete urgent combat missions were inferior to modified engines that lasted 6 months but completed missions standard engines couldn’t attempt.

This utilitarian calculation sacrificing long-term durability for immediate performance when circumstances required it represented sophisticated engineering judgment that Frank made intuitively. He recognized that wartime requirements differed from peaceime requirements and optimized accordingly. The broader impact of Frank’s achievement extended beyond the specific engine.

He demonstrated that formerly trained engineers didn’t have monopoly on valid engineering knowledge. Practical mechanics who understood equipment through hands-on experience possessed different but equally valuable knowledge. Both formal and practical knowledge contributed to effective solutions.

Modern military culture increasingly recognizes value of field expedient solutions and improvised modifications. The assumption that equipment must be used exactly as designed has been replaced with recognition that combat conditions require adaptation. Mechanics and soldiers who understand equipment well enough to modify it effectively are valued rather than discouraged.

Frank’s homemade Jeep engine stands as testament to practical engineering accomplishment achieved through unconventional means. The mockery that greeted the project revealed the prejudice that formal qualifications matter more than demonstrated capability. The success demonstrated that results matter more than credentials.

In final assessment, the engine that produced 200 horsepower from components designed for 60 represents triumph of practical knowledge over theoretical limitation. Factory specifications said it was impossible. Engineering textbooks would have predicted immediate failure. But Frank, who’d learned mechanics through family necessity rather than formal education, understood that specifications describe conservative limits rather than absolute capabilities.

The mockery transformed into respect, not because Frank proved he had credentials, but because he proved he had capability. The homemade engine built from salvaged parts outperformed factory equipment because Frank understood true component limits rather than published ones. The Brooklyn mechanic, who formal engineers dismissed, achieved what formal engineering said couldn’t be done.

190 to 210 horsepower from 60 horsepower engine. 15,000 hard miles under combat conditions. 6 months of continuous high-stress operation. Multiple missions completed that standard equipment couldn’t attempt. Five lives saved on August 14th during medical evacuation that two ambulances had failed attempting.

These were the results that mattered. The engine that everyone mocked became the engine that everyone wanted to replicate but couldn’t. Not because the modifications were secret, but because they required understanding that couldn’t be reduced to written instructions. Frank’s knowledge lived in his hands, his intuition, his willingness to try what others said was impossible.

That’s the complete story of how they mocked his homemade Jeep engine until it made 200 horsepower and changed how the army thought about vehicle modification and field engineering. Not through formal design or authorized procedures, but through practical knowledge, iterative experimentation and willingness to challenge assumptions about what was possible.

The mechanic they dismissed as amateur proved that sometimes the best engineers are those who never learned that certain things are impossible. The salvaged parts they said were garbage became components of engine that performed three times better than factory equipment. The modifications they predicted would fail immediately ran successfully for 6 months under conditions that destroyed standard engines in weeks.

Frank Castayano built impossible engine because he didn’t know it was impossible or rather he knew that impossible according to specifications didn’t mean actually impossible. It meant requires understanding beyond what specifications assume. And Frank possessed that understanding through experience that formal education didn’t provide.

The 200 horsepower Jeep engine that shouldn’t have existed but saved lives, completed impossible missions, and demonstrated that innovation comes from unexpected sources. The homemade modifications that violated every technical manual, but worked better than authorized equipment. the Brooklyn mechanic who proved that sometimes the best qualification isn’t formal degree but practical knowledge and willingness to question whether specifications describe limits or just starting points.

That’s the legacy. That’s the lesson. And that’s why the engine that everyonemocked became the engine that everyone remembered as proof that extraordinary performance comes from refusing to accept ordinary limitations.

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load