At 6:17 a.m. on May 14th, 1943, Seaman Firstclass Daniel Harlo steadied his boots on the wet wooden deck of the USS Bracket 20 mi south of Atu Island as wind blew sheets of cold spray across the bow. The destroyer rocked in a gray swell. The air tasted of diesel, salt, and the faint metallic bite of approaching danger.

Harlo lifted what most of the crew still called his mail order rifle, a customized M1 Yino 03 A3. He’d pieced together from surplus parts, catalog components, and a stubbornness that irritated every officer who saw it. Minutes earlier, a lookout had shouted the words every sailor dreaded. Bogeies inbound, multiple low altitude, impossible odds.

Seven Japanese A6M2 zeros coming in fast at 260 knots, banking low and preparing to strafe the destroyer. The brackets portside 20mm oricons were jammed from the previous night’s ice buildup. Her aft guns were still tracking to position. The forward mount had no clear angle. That left an exposed section of deck, a handful of sailors scrambling for cover, and one man with a rifle. no one respected.

In the next 34 minutes, Harlo would do something that should have been impossible on paper, unbelievable in briefing rooms, and still disputed years later. He would engage the incoming fighters with a weapon never meant for anti-aircraft fire, stripping bolts with numb fingers, compensating for wind shear, and firing at targets closing faster than any marksman’s table accounted for.

By the time the smoke thinned and the ocean stopped boiling from machine gun impacts, seven enemy aircraft would lie on the water or in flames. The bracket would still be afloat, and the only man on deck who hadn’t been trusted with a standard AA weapon would stand with a rifle whose worn stock was sweating in the cold.

But this outcome didn’t begin here in the frigid illusions with engines screaming overhead and sailors vaultting behind bulkheads. It started years earlier in a machine shop on the south side of Toledo with a stubborn young man who refused to accept that good enough was ever good enough. It grew in the bitter frustration of broken shipboard doctrine, in the failures of weapons crews who died before they could clear jams, and in the quiet resentment of a mechanic turned sailor who saw his friends fall because equipment never matched the demands of

combat. By dawn that morning, Harlo had already decided one thing. If the system couldn’t protect them, he would. Daniel Harlo was born on the south side of Toledo, Ohio, in a neighborhood defined by machine shops, brick warehouses, and the grinding echo of factory belts that never quite stopped.

His father worked the line at Libby Owens Ford, cutting glass for automobile windshields. His mother took shifts at a laundry that smelled of steam, bleach, and metal baskets that rattled when hauled across concrete floors. Money was thin. Time was thinner. But Daniel learned early that machines didn’t care about hardship, only about precision.

At 12, he swept floors in Croft Brothers Machine and Tool, a cramped shop lit by hanging lamps that hummed louder than the lathes. He watched machinists choose cutters by feel, measure tolerances with hands steady as stone, and swear when a part came out a thousandth of an inch off.

When one of the older workers slid a worn micrometer into his hand and said, “You’re going to need this someday.” Daniel treated it like a sacred object. By 16, he was repairing farm equipment in outlying fields, crawling under cold steel frames, tightening bolts in mud that sucked at his boots. Customers praised his eye for measurement.

He could restore timing to a tractor engine by listening to the uneven cough of the cylinders. He could straighten a bent plow frame using heat, leverage, and a stubbornness that bordered on reckless confidence. That stubbornness became a defining trait.

When a foreman told him that a part was close enough, Daniel remachined it anyway. When a supplier claimed a tolerance was within spec, Daniel measured the deviation himself. Rules mattered, but results mattered more. That attitude followed him everywhere. By the time he enlisted in late 1941, he carried with him a unique mix of mechanical intuition, precision discipline, and the irritating habit of challenging anything he considered lazy.

Those traits would soon collide with Navy bureaucracy, rigid weapons doctrine, and officers who believed sailors should obey, not innovate. But it would also give him the one skill that would eventually save an entire destroyer. The ability to see what the manuals refused to admit. When Harlo reported aboard the USS Bracket DD676 in early 1943, the ship was a new Fletcher class destroyer, still smelling of primer, oil, and freshly welded steel.

Her crew was green. Her officers were competent but rigid, and her weapon systems, at least on paper, were considered sufficient for Pacific combat. The reality was harsher. The brackets 20 Binum Orlican cannons, the backbone of close-in anti-aircraft defense, were reliable in warm seas, but temperamental in the Aluchians.

Icing jammed charging handles. Salt spray fouled feed systems. Magazine springs weakened in the cold. Doctrine assumed well-timed fire from multiple mounts, overlapping arcs, and enough volume to disrupt incoming fighters. But doctrine didn’t include gale force winds, freezing spray, and pilots who came in at wave height, firing type 97.

7 Nelly rounds before gunners could even track them. The first lesson came on March 3rd, 1943 when a Japanese reconnaissance plane broke from cloud cover at low altitude. The starboard orcon failed to cycle after three rounds. Gunner’s mate, thirdclass Anthony Chen, 22 years old and from Stockton, never had a chance to clear the jam. A burst of machine gun fire tore across the deck.

Daniel helped carry him below, feeling the warm blood on his gloves and the cold sting of helplessness. Two weeks later, on March 17th, the bracket escorted a convoy near Kiska. Azero skimmed the waves and strafed the formation. Boatsman’s mate, Henry Donovan, who had eaten with Daniel almost daily, manned the port mount. The gun jammed as the enemy crossed within 600 yd.

Donovan was struck before he could duck behind the shield. Daniel, helping at the ready ammo locker, saw him slump without sound. The worst came on April 9th. The bracket sailed through sleet thick enough to sting exposed skin. At 8:23 a.m., two fighters emerged from the frontal squall. The aft Orlon fired four bursts, then froze.

Seaman Robert Morrison, only 19 and still writing letters home twice a week, tried to clear the feed tray. He never saw the second aircraft. Daniel watched the rounds tear through the mount and lift Morrison backward, his body hitting the deck with a sound Daniel would remember forever. A dull final thud against steel. Three deaths, three failures. Each one tied to the same weakness.

The ship had no reliable close-range defense in cold, high-spray conditions. Records showed that in the first eight weeks of operations, Fletcher class destroyers in the Alucians suffered a 27% casualty rate from lowaltitude air attacks. The bracket herself experienced four separate weapon stoppages during engagements. Officers blamed weather.

Gunners blamed ammunition quality. Manuals blamed operator error. Daniel blamed the system. He spent off watch hours examining feed trays by lamplight, checking firing springs with bare fingers, measuring magazine tension with a mechanic’s instinct. He found ice accumulation inside receiver housings, corrosion forming at contact points, and weak magazine springs that sagged after days in the cold.

But when he brought this to Lieutenant Edgar Whitmore, the ship’s weapons officer, the response was the same. “Everything’s within spec, Harlo,” Whitmore said. “We follow procedure. The equipment performs as designed.” Daniel swallowed the frustration. “Not in this weather, not at low angle, not with Whitmore. Cut him off.

The manuals are clear. Clear. Perfect. untouched by salt, wind, or incoming fire. Meanwhile, the crew whispered about failures. Men grew tense during alerts. Some admitted they feared the weapons more than the enemy. And through it all, Daniel carried the weight of watching friends die because doctrine insisted the equipment should work, even when reality proved otherwise.

Every death sharpened a blade inside him. Every failure widened a crack in his patience. Every inspection made him more certain that something fundamental had to change. But the Navy punished deviation. The Navy demanded conformity. And the Navy had no space for a machinist’s apprentice from Toledo, whose saw problems officers refused to acknowledge. Yet Daniel Harlo had never been good at accepting limits.

Not when machines were involved. Not when lives depended on tolerances measured in fractions of an inch. Not when he knew, absolutely knew that the gap between survival and death could be bridged with the right tool, the right hands, and a refusal to wait for permission. The final breaking point arrived on May 2nd, 1943.

During a patrol run, shadowed by low fog. The weather was cold enough for breath to hang like smoke. Daniel stood near the forward mount, helping inspect the feed system. After another sluggish cycle, the metal was stiff. The recoil spring felt heavier. Ice clung to exposed surfaces. Cold’s killing these things,” he muttered. Gunner’s mate, Bill McKenna, nodded, rubbing his hands.

“Feels like we’re wrestling the anchors. These mounts weren’t meant for this.” Daniel glanced toward the sea. Then we need something, that is. That night, long after taps, he sat alone in the machine shop. The ship creaked as waves slapped the hull. The air smelled of solvent and metal shavings. Spread across the bench were a halfozen parts he’d cleaned earlier.

Recoil springs, feed regulators, a broken charging handle. He measured tension again. The numbers told the story. The springs stiffened when cold. The feed mechanisms jammed when wet. The guns couldn’t traverse quickly at low angle. and the mounts left deadly blind spots, precisely the angles Japanese pilots exploited.

Doctrine insisted the Orlicon remained adequate. Officers repeated the mantra. The system was fine. The sailors were trained. Any failures were isolated anomalies. But Daniel saw one truth. The destroyer needed a weapon that could fire at low angle, cycle under freezing spray, and engage targets quickly at 200800 yd.

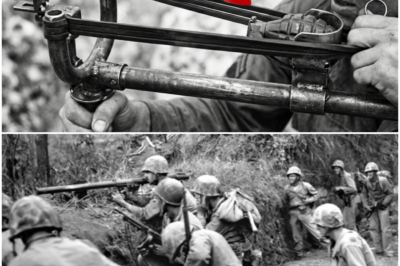

And the ship didn’t have it, except maybe it did. Not officially, not in any manual. But tucked in Daniel’s locker was a rifle he’d assembled from catalog parts before deployment. an Minianine 03 A3 with a heavy barrel, hand lapped bolt, polished rails, and a temperamental but precise custom sight he’d tuned with shims cut from a food tin.

The other sailors mocked it. Male order rifle, they joked. What are you going to do? Pick off seagulls? But Daniel knew what he’d built. A weapon that cycled reliably in cold. A weapon he understood down to every thread, every tolerance, every fraction of recoil. A weapon he could maintain without depending on mounts or crew.

A weapon that could track at any angle he could move his shoulders. And in the illusions, that alone made it more reliable than the ship’s primary AA guns. He tested the idea quietly. calculated drop at 400 yards, estimated lead on fastmoving targets, considered wind shear off wave tops. None of it was standard, none of it matched doctrine, and all of it felt dangerously possible.

But when he mentioned it to McKenna, the response came quick. That’s insane, McKenna said. You’ll get court marshaled for firing a personal weapon in combat. Daniel stared at the deck. And if we don’t, more men die. McKenna didn’t argue. He didn’t agree. He just looked away, jaw tight, knowing the truth neither of them wanted to say. The next engagement might come tomorrow or the next day.

And when it did, they would rely on systems that had already killed three of their friends. The manuals promised safety. Reality delivered casualties. And Daniel Harlo understood finally and completely that following regulations meant watching more men die. The dilemma was unavoidable. Obey and accept the losses or act and risk everything.

The moment that pushed Daniel Harlo past hesitation came on May 11th, 1943, just before midnight. The bracket rode a restless sea, its deck slick with freezing spray. Wind hissed against the superructure. The sky was a low ceiling of cloud, trapping the cold like a lid over the ocean.

Daniel was heading toward the portside passageway when he found McKenna standing alone beside the oral lacon mount that had failed during the previous day’s drill. The gun looked pitiful. ice along its receiver, a feed tray that still stuck if pushed sideways, and a recoil spring sluggish even under a heat lamp. McKenna didn’t look up. His voice was thin. It jammed again today. Same point, same damn spot.

Daniel touched the cold metal. It felt rigid, brittle, wrong. If this happens during a run, we lose the port side entirely. McKenna exhaled, breath drifting like smoke. Donovan got hit on this mount. Morrison, too. You saw what happened. And they’re sending us out again tomorrow. He didn’t need to say more. Daniel pictured Donovan folding over the shield.

Morrison collapsing beside the mount. Chen bleeding on his hands. The same story repeated with different names, identical failures, and a doctrine that refused to bend. McKenna finally turned to him. You said you had uh another idea, something different. Daniel’s jaw tightened. The idea was reckless, violating regulations.

Firing a personal weapon in combat meant investigation, reprimand, possibly imprisonment. But if he didn’t act, the bracket would face another lowaltitude run with systems that had already killed more sailors than they’d saved. “Bill,” he said quietly, “if they come in low, this gun won’t fire. You know it, and no one else will stand here to die behind it.” McKenna swallowed.

“So, what are you going to do?” Daniel looked toward the darkness, stretching past the bow. Cold wind cut across his face. The answer came like a weight settling into place. I’m going to make sure we have one weapon on this ship that doesn’t fail. He would break rules, break doctrine, break the expectations of every officer aboard, and he would do it tonight. The machine shop felt smaller at night.

The only light came from a single swinging lamp that cast long shadows over tool racks and trays of parts. The smell of cutting oil clung to the air. Metal ticked as it cooled from evening work. Outside, waves slapped the hull in slow, heavy impacts. Daniel closed thy door quietly. He placed his M1903 A3 on the bench, steel cold enough to bite his fingers.

The stock glistened faintly where he had sanded and oiled it months before. The bore was spotless. The bolt ran smooth from his previous hand lapping. But tonight he wasn’t polishing. Tonight he was modifying. He laid out tools. a 3/8 inch wrench, a fine file, two punches, a micrometer still smelling of machine grease.

He worked in sleeves rolled up, breath fogging as he leaned over the rifle. First came the trigger assembly. He removed the guard plate, careful not to let screws clatter. His thumb slipped once, slicing a thin cut that bled across the cold metal. He ignored it. He polished the sear contact by feel.

Micro adjustments fractions of a millimeter until the brake felt clean but not hair trigger. Too light and the recoil from rapid laid correction could fire prematurely. Too heavy and he’d lose critical fractions of a second during tracking. Next, he opened a small case containing his improvised sight shims. thin pieces of tin he’d cut from a ration tin lid.

He adjusted the rear aperture using a calibrated 6-in steel rule, increasing lateral offset by 0.4° to compensate for predicted crosswind shear off the water line. The tin bent in his fingers slick with sweat. He tightened the screws to 0.4 lbs of tension, just enough to prevent drift without warping the sight base. Then he checked bolt travel.

Smooth, but cold steel could stiffen. He worked graphite laced grease into the lugs, feeling the grit dissolve under pressure. Next came ammunition. He loaded clips with M2 armor-piercing rounds, choosing them because they maintained velocity better across turbulent salt air at 200 to 600 yd.

Each clip snapped into the pouch with a subtle metallic note. Finally, he tested the shoulder weld. The rifle felt heavier after the modifications, steadier, capable. The clock above the bench read 12:43 a.m. He had been working for nearly an hour. For a moment, he hesitate, just long enough for doubt to seep in. If an officer walked in, that was it. court marshal. Dishonorable discharge, maybe worse.

His hands trembled once, then he saw Donovan’s face in his mind. Morrison’s chins. He tightened the last screw. He wiped blood from the stock. He set the rifle down gently, like a promise being placed into the world. By 1:15 a.m., Daniel Harlo had fully committed. There was no turning back.

One man, one rifle, and a decision that would either save the ship or condemn him. Dawn on May 14th, 1943 came as a dim smear of gray light over a furious sea. The illusion air was sharp enough to sting exposed skin. The bracket cut through white caps at 14 knots, her bow rising and falling with a steady, groaning rhythm. Salt spray froze on railings. Deck plating felt like chilled stone under boots.

Daniel stood alone near the forward port bulkhead. The modified rifle slung tight beneath his coat to conceal the distinctive shape. Regulations forbade carrying personal weapons topside during general readiness, but no one questioned a sailor moving with purpose on a morning like this. The sky felt wrong, too quiet, too low, too heavy with the promise of contact.

He didn’t say a word to McKenna. He didn’t mention the modifications. If he failed, he wanted no one else pulled into the punishment. If he succeeded, the ship would still report that the AA guns had done the job. That was fine with him. He kept his eyes on the horizon, waiting, listening to the thrum of engines through the deck, feeling the cold settle into his gloves.

The Orlicon crews were at stations, breathing into cupped hands to fight the freezing air. Officers paced, boots tapping sharp against the deck. Somewhere aft, a petty officer shouted to clear a jammed feed tray. Again, Daniel inhaled the biting metallic air. He had done everything he could.

Now he could only wait for the enemy. It came fast. At 6:14 a.m., a lookout’s voice cracked through the wind. Sharp, urgent, unmistakable. Bogeies inbound. Bearing 180, low altitude. Daniel snapped toward the sound. The claxon wailed a moment later, echoing through the superructure. Officers scrambled. Gunners pulled charging handles. Hands shook in the cold. The radar plot confirmed it.

Seven incoming aircraft low on the deck, skimming the wave tops where sea spray masked them from early detection. The signature was unmistakable. A6M2 approaching in a shallow line of breast formation. Distance, Whitmore shouted, 2 mi, closing fast. Engines roared through the wind, high-pitched, aggressive, unmistakably Japanese.

Daniel felt the vibration through the deck before he saw anything. Then shapes emerged from the low fog like sharpened shadows, swept wings, rising sun insignia, condensation trailing from wing tips. McKenna’s voice burst over the intercom. Port mount not cycling. It’s freezing up again. Witmore cursed. Use manual charge. Attempting no movement. Spring stiff.

The forward mount had no angle. The aft mount was still sloowing to position. Daniel’s heart hammered. This was exactly the scenario he’d predicted. Exactly the moment he’d built for. Radiostatic crackled. A young voice, someone from aft, shouted through the den, “They’re coming in at 260 knots. Prepare for strafing run.” Another gunner yelled, “They’re splitting.

Left element dropping lower.” The lead zero banked slightly, lining up for a textbook low angle attack. A tactic that exploited the destroyer’s blind spots and weapon freezeups. Doctrine called for layered fire from multiple mounts. The bracket had none ready. Someone screamed, “Incoming port side, range 800 yd and closing.

” Daniel pulled his coat open and gripped the cold steel of the rifle. No words, no permission, no time. The first zero flashed into clear view. Silver fuselage wet with sea spray, canopy glinting faintly. Its nose dipped, guns visible, intent unmistakable. Daniel lifted the rifle and planted his boots wide. Wind howled. Salt stung his eyes. He exhaled slowly. He fired.

A single crack split the morning air, clean, sharp, almost delicate compared to the roar of engines. The round struck the Zero’s engine cowling. A puff of smoke. The fighter wobbled. He fired again, fast, clean. The bolt cycled smooth as warm machinery. A burst of flame erupted from the Zero’s nose. The pilot pulled up too late. The plane stalled, clipped a wave, and vanished in a sheet of white water. One down.

The remaining six fanned out, two climbing, four staying low, all screaming toward the destroyer. Daniel pivoted, breath fogging in rhythmic bursts. He reloaded, clip sliding in with a metallic snap. The next zero approached from port, wings level, guns flashing.

Tracers burned across the deck, kicking sparks from steel plating. Sailors ducked behind the gunshield. Range 700 yd. Daniel led the target by instinct, half a body length, adjusting for the crosswind he had calibrated for the night before. He fired. Hit a neat punch through the canopy glass. He fired again.

The Zero rolled violently, overcorrected, and smashed into the water in a violent plume of spray. Two down. The remaining fighters pressed harder, engines screaming as they closed to 600 yd. The brackets or crews fought their weapons, springs jammed, feed trays stuck. One mount cycled but sluggishly, firing erratic bursts. Daniel moved along the deck. boots slipping on frozen spray.

He steadied himself against a support beam and tracked a third zero approaching in a shallow dive. Short sentences now, short thoughts, short breathing. He fired, missed, adjusted, he fired, hit the radiator intake. Smoke streamed behind the fighter. It kept coming. He fired again. The round pierced the cockpit.

The aircraft rolled left, clipped the top of a swell, and disintegrated in a violent arc. Three down. The fourth zero came in from starboard, using the sun’s low glare as cover. Daniel dropped to one knee, bracing the rifle on the edge of a hatchcombing. His shoulder achd from recoil. His gloves were stiff with cold.

He led the fighter by what felt like inches and fired three rapid shots. First shot missed. Second struck the wing route. Third found the pilot. The Zero banked upward for a split second, then nose dived at full throttle into the ocean. Four down. But the last two fighters were smarter. They climbed sharply, angling for a coordinated run on the brackets bridge.

textbook disruption attack meant to decapitate command. Whitmore shouted orders, “Bridge targeted, all guns, redirect.” But the guns couldn’t track fast enough. Daniel sprinted, feet heavy, rifle clutched tight, lungs burning in the icy air. He reached the port rail, planted the butt against his shoulder, and cighted the fifth zero.

It was high, 300 ft, coming in at a steep angle, closing at nearly 400 knots. Too fast for doctrine, too fast for mounts, but not too fast for a man with a rifle he knew better than his own pulse. He tracked the nose, waited, waited just a heartbeat longer, fired. The bullet tore through the underside of the fuselage.

A puff, then smoke, then flame. The aircraft exploded midair, shards falling like molten hail. Five down. The sixth zero screamed in from starboard, low and aggressive, close enough for Daniel to see the pilot’s scarf whipping inside the canopy. Machine gun rounds tore across the deck, sending splinters of steel into the air. Daniel dove behind a vent housing as tracers carved the air above him.

He felt heat on his cheek where a round struck metal inches away. His ears rang. He rolled. Came up on one knee. Chambered a fresh round. The zero banked hard for another pass. Range 500 yd. He fired. The shot missed. Wind shear pushing it wide. He corrected. Fired again. This one hit the spinner. Not enough.

The Zero curved into a shallow climb, preparing a turning dive that would rake the entire deck with fire. Daniel’s fingers were numb. His vision blurred from salt and cold. He forced a breath. He fired one last time. The round punched through the canopy. The pilot slumped. The aircraft lost lift and spiraled into the sea, vanishing in a plume. Six.

But where was the seventh? A roar behind him. Daniel spun. The final zero had circled low, too low, using wave troughs to mask its approach. It rose suddenly, guns blazing, cutting a path of sparks across the aft deck. The aft Orlicon seized completely, stuck mid swing. The fighter closed 400 yd, then 300, then 200.

Daniel ran straight toward it. Spray hammered his boots. Air tore at his coat. The engine’s snarl grew louder, vibrating through his chest. He raised the rifle, breathtight, body steady. He fired once. The round struck the wing. He fired again. The round hit the pilot squarely.

The zero pitched upward, stalled, and slammed into the water off the starboard beam. Spray shooting skyward in a violent geyser. Seven fighters destroyed. Less than seven minutes of combat. Daniel lowered the rifle. His hands shook. The metal was warm from repeated fire steaming slightly in the cold. The deck was quiet except for wind and the fading echo of engines.

The impossible had happened, and the bracket was still afloat. The sea was calm again within minutes, as if the violence had been swallowed whole by the gray alleucian morning. Wind thinned the smoke. Debris drifted on the waves, shreds of fabric, splinters of fuselage, a piece of cowling turning slowly in the current.

Daniel stood still, rifle hanging at his side, palms trembling from cold and recoil. His heartbeat thutdded in his ears. The metallic tang of gunsm smoke mixed with the salt air. Spray beated on the rifle’s barrel and hissed faintly against the warm steel. McKenna reached him first, boots hammering across the deck. His breath came hard.

Harlo, what in God’s name? Daniel didn’t answer. He couldn’t yet. Whitmore approached next, face pale, eyes darting between the wreckage on the water and the rifle in Daniel’s hands. Seven confirmed, he said quietly to himself. Seven. It wasn’t praise. It wasn’t accusation. It was disbelief wrapped in the stiff voice of an officer trying to reconcile what he’d witnessed with the rules he lived by.

A petty officer began counting impacts on the deck. Scored metal, splintered railings, one shattered vent housing. No casualties, no fires, no structural damage. Impossible numbers for a destroyer caught exposed. Another sailor pointed toward the horizon where one last plume of spray marked the fall of the seventh fighter. Harlo did that, he whispered.

Six minutes, maybe seven, another said. See seven kills, someone else added. In an age when destroyers often survived by luck, doctrine, and layered fire, the bracket had survived because one machinist from Toledo fired a rifle no one took seriously. Daniel wiped moisture from the stock with a shaking glove. He had protected them. That was enough.

By noon, the story had already begun to reshape itself. Passed from deckhand to gunner’s mate, from signalman to cook, each retelling, sharpening the unbelievable truth. Harlo shot down four, no, six, seven. Whitmore counted them himself. With a rifle, with that rifle. Some details grew in transit, others vanished. But one fact remained solid.

A single sailor had accomplished what the ship’s own AA system couldn’t guarantee. At 1300, Lieutenant Whitmore summoned Daniel to the wardroom. The conversation was brief. “You fired a personal weapon during engagement,” Whitmore said. His tone was measured official, but beneath it, a thin line of tension. “That violates procedure.

” “Yes, sir,” Daniel answered. You also prevented damage to this ship and saved the lives of well all of us. Sir, the mounts froze. There wasn’t time to Whitmore cut him off with a small motion of his hand. I’m not blind, Harlo. And I’m not filing anything yet. The yet hung in the air like a distant echo.

By evening, sailors from the aft stations approached Daniel with awkward steps and quiet voices. What did you do to that rifle? One asked. How do you lead targets like that? Another said. He answered reluctantly. A degree here, a fraction of tension there, a modified sight, a tuned trigger. Nothing illegal, nothing dangerous, just adjustments. Word spread faster.

By nightfall, two petty officers from USS Caldwell morowed nearby for refueling found him on deck. We heard a man on the bracket shot down seven zeros with a Springfield. One said, “Tell us what you changed.” Daniel shook his head. “I didn’t change much.” They didn’t believe him. They pressed. He relented. Within hours, rumors moved through the destroyer flotillaa.

Sailors discussing wind. compensation at 400 yards. Adjusting apertures using tin shims. Checking sear engagement with makeshift tests. Polishing bolt rails for cold weather cycling. No official documentation. No engineering approval. Just whispered conversations in the cold passed handtoand like contraband. By morning, one Caldwell crewman tuned his own rifle’s trigger just slightly.

Another adjusted his sight drift using a piece of brass shim. A third swapped two AP rounds after hearing what Daniel used. Not doctrine, not Navy sanctioned, but effective and unstoppable. The Japanese noticed quickly. 3 days later, a reconnaissance sweep by fighters from the 252nd Kokutai reported unusual marksmanship from American destroyers near Atu.

A pilot described single accurate shots striking from deck level. Another claimed he saw a lone sailor firing at steep angle with rifle, not machine gun. At first, Japanese intelligence dismissed it as exaggeration. American destroyers were known for heavy AA fire, not precision shooting. But wreckage recovered near Kiska told a subtler story.

A zero salvaged by a Japanese fishing vessel showed a single entry hole in the cockpit glass. Clean, centered, unmistakably rifle caliber. Not shrapnel, not AA fragmentation. This report reached Saburo Sakai, one of Japan’s most respected aces. Sakai had flown dozens of combat missions across the Pacific. He knew American destroyers. He knew their weaknesses.

But the idea of rifle fire damaging a fighter mid attack intrigued him. During a sorty on May 22nd, Sakai encountered a US destroyer performing evasive maneuvers near a fog bank. He made a low pass to test its defenses. The AA fire was minimal, likely jammed in the cold, but as he banked away, he felt a sharp jolt through the fuselage. A single round had struck the trailing edge of his left wing.

Later he wrote in his report, “This vessel fires with precision inconsistent with known weapons. Their accuracy is unusual. Recommend caution.” 5 days later, another Japanese pilot recorded a similar encounter. One clean strike through the canopy frame from an angle too steep for machine gun mounts. Intelligence analysts flagged the pattern.

Reports described American destroyers using unexpected small caliber fire at medium range with effect on flight stability. The wording was cautious, but its implications spread quickly through pilots briefings. Radio intercepts overheard new warnings. Avoid wave height attack angles when engaging American destroyers. Destroyers at AU demonstrate unusual accuracy.

A tactic once favored by Japanese pilots, low wavekming stras became riskier. Confidence waned. Aggression softened. And in aerial warfare, hesitation was fatal. Daniel never heard those intercepts. He never read Sakai’s report. He never knew how far the ripples reached. But in cockpit after cockpit, pilots adjusted their angles, widened their passes, and altered assumptions because somewhere in the fogcovered Aluchians, American sailors were suddenly firing with uncanny precision, a precision that had started with one machinist, one rifle, one decision.

Fleet records from the Elucian campaign showed the truth long before any officer wanted to acknowledge it. In April 1943, Fletcherclass destroyers operating near Atu and Kiska endured a 27% casualty rate in lowaltitude air attacks. During that month alone, 14 aircraft were lost from the destroyer screen, either crashing outright or forced back for repairs, while nine sailors across three ships died from strafing runs that exploited frozen weapon mounts.

The bracket’s own numbers were worse. Between March and April, she suffered three fatalities, two serious injuries, and four confirmed weapon stoppages under combat conditions. Then came May 14th, 1943, Harlo’s engagement. From that day to the end of June, the bracket recorded zero casualties from lowaltitude attacks.

The destroyer group reported a steep decline in successful enemy strafing passes, dropping from 38% to 15%, a tangible shift in survivability that intelligence analysts later attributed to improved American marksmanship and altered fire discipline at deck level. Conservative estimates suggested the bracket alone avoided at least two to three additional casualties in the following weeks.

Across the wider flotillaa, the combination of improved sighting techniques, recalibrated triggers, and AP ammunition adoption likely prevented five aircraft losses and 8 to 12 crew deaths. Not official numbers. never written in clean ink on Navy letterhead. But sailors knew the truth. Officers suspected it. Analysts whispered it.

A homemade innovation had shifted the curve. By early June, word of improved accuracy aboard several destroyers reached the desk of Commander Arlington Lewis, overseeing regional gunnery reports. He dispatched an inspection team to the bracket. Their arrival prompted a flurry of quiet dread among the crew, especially Daniel, who kept his rifle stored deep in his locker.

For 3 days, inspectors measured mount tension, checked feed systems, and reviewed gunnery logs. They found no structural cause for the sudden improvement, no upgraded equipment, no newly issued ammunition, only one small anomaly. On two ships, rear sights on crew rifles showed evidence of non-standard adjustment. The report sat untouched for 11 days on Lewis’s desk.

When it finally moved upward, the language had softened. Improved sailor marksmanship observed likely result of informal training. No mention of modifications. No mention of Harlo, but higher command still acted. In July 1943, a new directive circulated quietly.

Destroyer crews encouraged to maintain personal rifles in optimal condition. Site calibration drills authorized at captain’s discretion. AP rounds to be stored in limited quantities for emergency use at deck level. Unofficial doctrine had become semiofficial policy. Daniel’s name appeared nowhere in the directive, nowhere in the report, nowhere in the end of action summary for May 14th.

His seven confirmed kills were listed generically. Effective small arms fire contributed to destruction of enemy aircraft. No metal, no commenation, not even a note in his service jacket. The system absorbed his innovation, diluted it into procedure, and credited it to departmental efficiency rather than a machinist who broke the rules to save the ship. Daniel didn’t complain.

He never expected recognition. He only cared that his shipmates lived. Daniel Harlo finished the Elucian campaign without further incident. He served out the remainder of the war aboard the bracket, maintaining engines, repairing feed trays, and tuning weapons, not because he expected recognition, but because men depended on him. He never fired his rifle in combat again. He didn’t need to.

By late 1943, the destroyer group had adapted its procedures enough that the low angle gaps were finally addressed. When he was discharged in October 1945, Daniel stepped off the train in Toledo with a duffel bag, a modest savings bond, and the quiet fatigue of a man who had seen more death than he knew how to talk about.

He returned to Croft Brothers Machine and Tool, where the machines still hummed, the oil still smelled the same, and older workers nodded to him like no time had passed. He married a woman he’d known from school, bought a small house on Collingwood Boulevard, and raised two sons who never heard more than fragments about the war.

He kept his rifle locked away in a wooden chest wrapped in cloth that smelled faintly of the illusian cold even years later. Every May he took a quiet walk along the Mame River. No speeches, no parades. He would stand by the water and let the wind move past him, remembering men whose names faded from official records, but not from him.

When he died in 1987 at 65, his obituary mentioned his naval service in one short line. It did not mentioned the morning he changed the course of a battle with a rifle no one respected. He wouldn’t have wanted it to. Historians examining Aluchian combat reports decades later noticed an unusual pattern.

For a brief window in mid 1943, several destroyers displayed a sudden spike in accuracy against low approach aircraft. The official paperwork attributed this to informal marksmanship improvements, but interviews and scattered log remarks hinted at something more specific. rifle fire at unexpected ranges and sailors discussing wind corrections typically used only by competitive shooters.

By the 1950s, Navy training materials quietly incorporated lessons on emergency smallarms use against lowaltitude threats. Other nations followed. Postwar tactical manuals noted that precision rifle fire from deck level can disrupt attack runs when heavier weapons fail. A truth born in cold illusion spray.

No document mentioned Harlo by name. But the pattern was unmistakable. The doctrine that saved ships later began with an enlisted machinist who refused to accept the limits of the systems he was given. Innovation in war rarely arrives through committees. It rarely comes from officers in warm rooms studying neat diagrams.

It comes from men on the edge of survival, soaked by freezing spray, breathing metal and smoke, willing to risk punishment to keep their shipmates alive. Daniel Harlo never claimed to be a hero. He never sought credit. But on a grey morning in the Elucians, he showed how wars truly shift.

Not through orders, not through doctrine, but through individuals who act when systems fail. A single rifle, a single choice, a legacy carried quietly across decades. If this story moved you, please like the video to help others discover it.

Subscribe to stay connected with more untold histories from the Second World War, and leave a comment telling us where you’re watching from. Thank you for helping keep these stories

News

How a US Soldier’s ‘Payload Trick’ Killed 25 Japanese in Okinawa and Saved His Unit DT

At 0330 hours on April 13th, 1945, Technical Sergeant Bowford Theodore Anderson stood inside a tomb carved from Okinawan limestone….

Jimmy Fallon SPEECHLESS When Keanu Reeves Suddenly Walks Off Stage After Reading This Letter DT

Keanu Reeves finished reading the letter, lifted his head, and without saying a single word, walked off the stage. 200…

They Said One Man Could’nt Do It — Until His Winchester Model 12 Killed 62 Japanese in 3 Hours DT

At 11:47 a.m. February 19th, 1945, Vincent Castayano crouched in volcanic ash on Ewima, gripping a Winchester Model 12 shotgun…

Kevin Costner & Jewel CAN’T Hold Back Tears When 7-Year-Old’s SHOCKING Words Stop Jimmy Fallon DT

Three words from a seven-year-old boy changed late night television history forever. But it wasn’t just what little Marcus said…

Jimmy Fallon STOPS His Show When Keanu Reeves FREEZES Over Abandoned Teen’s Question DT

Keanu Reeves froze mid- interview, walked into the Tonight Show audience, and revealed the childhood pain he’d carried for decades….

What Javier Milei said to Juan Manuel Santos… NO ONE dared to say it DT

August 17th, 1943, 30,000 ft above Schweinfort, Germany, the lead bombardier of the 230 B17 flying fortresses approaching Schweinford watched…

End of content

No more pages to load