August 17th, 1942. Somewhere over the Solomon Islands, 23,000 ft above the Pacific Ocean, Second Lieutenant John L. Smith, USMC, adjusted the throttle of his F4F Wildcat fighter and scanned the horizon through sweat-foged goggles. Behind him, stretched in loose formation, flew 11 more Wildcats from Marine Fighting Squadron 223.

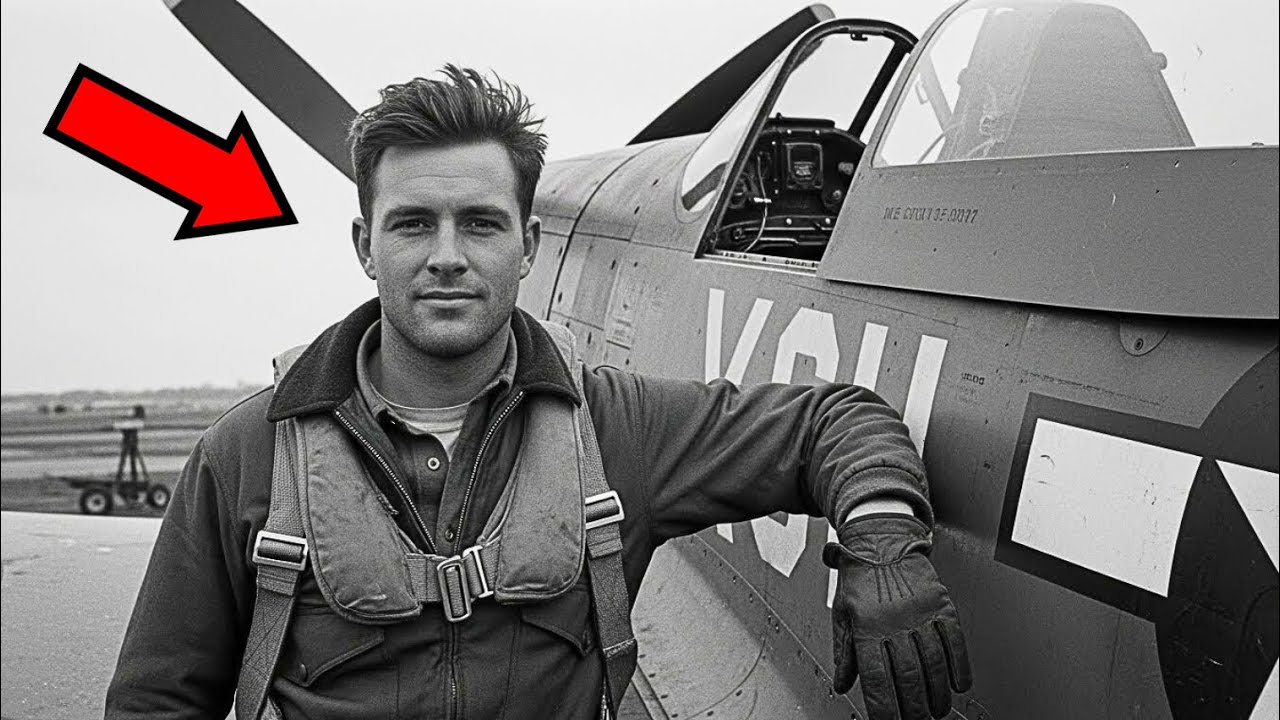

Smith was 27 years old, older than most fighter pilots. He’d learned to fly not at Pensacola or any distinguished naval air station, but in a rickety biplane over Oklahoma wheat fields, paying for lessons by working his father’s farm. When he’d arrived at Guadal Canal 2 days earlier, the Annapapolis graduates and established Navy pilots had been barely able to hide their contempt. A farm kid from Oklahoma who’d learned to fly in a crop duster.

What did he know about aerial combat against the Imperial Japanese Navy’s elite pilots? The Zero fighters flown by Japanese naval aviators were considered the most advanced carrier fighters in the world. Their pilots, veterans of China and the Philippines had destroyed every Allied air force they’d encountered. The radio crackled.

Contact bogeies at 2:00 high. zeros, approximately 20. Smith counted the enemy fighters descending from the sun. 20 zeros against 12 Wildcats. The odds seemed impossible. The Mitsubishi A6M0 was faster, more maneuverable, could climb higher, and turn tighter than the stubby Grumman Wildcat. On paper, this engagement should end with 12 American pilots dead or captured.

But Smith wasn’t fighting on paper. He was fighting with knowledge earned over Oklahoma farmland, understanding aircraft performance at gut level that no academy could teach. He’d learned to fly by feeling the machine, reading the wind, understanding the limits of engines and wings through thousands of hours of practical experience that wealthy Navy pilots considered beneath them.

What happened in the next 18 minutes would revolutionize American fighter tactics in the Pacific. The farm kid they’d mocked was about to demonstrate that formal training, prestigious backgrounds, and social class meant nothing in combat. Results mattered, and John Smith was about to deliver results that would change how America fought the air war.

The mathematics of survival were about to be rewritten, not in training manuals or tactical briefings, but in the sky above Guadal Canal, by a pilot who understood that victory came not from dogfighting zeros on their terms, but from using American advantages, the enemy didn’t expect the farm boys beginning. John Lucian Smith was born June 26th, 1914 in Lexington, Oklahoma.

His father owned 320 acres of wheat and cattle land. The family wasn’t wealthy, but they weren’t poor either. Middleclass farmers who worked their own land and expected their children to do the same. From age 12, Smith worked the farm full-time during summers and after school, driving tractors, repairing equipment, managing livestock.

He developed an intimate understanding of machinery, how engines performed under stress, how mechanical systems failed, and most importantly, how to coax maximum performance from equipment that wasn’t quite adequate for the job. In 1931, at age 17, Smith saw his first airplane up close. A barntormer named Jack Thompson landed in a pasture outside Lexington, offering rides for $2.

Smith spent an entire summer savings on a 10-minute flight. He was hooked immediately. Thompson, recognizing genuine interest, offered a deal. Work as his mechanic and ground crew, and he’d teach Smith to fly. For the next two years, Smith worked Thompson’s air shows, learned basic maintenance, and accumulated flight hours in a 1927 travel air biplane, held together with wire and hope.

This education, rough and practical, taught Smith things formal flight training often missed. He learned to fly with marginal equipment. He learned to compensate for engine problems mid-flight. He learned to read weather by field. He learned that expensive, sophisticated equipment wasn’t necessary if you understood basic principles thoroughly.

In 1936, Smith enrolled at the University of Oklahoma, paying tuition through farmwork and odd jobs. He joined the ROC program, attracted by the possibility of learning to fly military aircraft, but financial pressures forced him to leave. After 2 years, he returned to the family farm, apparently resigned to a life of agriculture. Then came December 7th, 1941. Pearl Harbor changed everything.

Smith, now 27 and technically too old for flight training, applied for the Marine Corps Aviation Cadet Program. His application listed 200 hours of civilian flight time in obsolete biplanes. Most applicants had zero hours, but came from prestigious universities. The Marines, desperate for pilots, accepted him anyway.

Flight training at Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, should have been Smith’s opportunity to prove himself. Instead, it became an exercise in class discrimination. The younger cadets, many from Ivy League schools, viewed the Oklahoma farm boy with open disdain. Enson Robert Clark, who trained alongside Smith, later recalled the atmosphere.

John was older, spoke with an Oklahoma accent, talked about farming and crop dusting. The East Coast guys treated him like a hick. They assumed he’d wash out. Nobody expected him to succeed. But Smith possessed advantages his critics didn’t recognize. His hundreds of hours in marginal aircraft had taught him to fly by instinct.

While other cadets struggled with basic maneuvers, Smith flew with unconscious competence. His mechanical knowledge gained from repairing farm equipment and barnstormer planes gave him deep understanding of aircraft systems. Most critically, Smith had learned to solve problems creatively. Farming meant working with inadequate resources, improvising solutions, achieving results despite limitations.

This mindset, which privileged cadets considered primitive, would prove decisive in combat where perfect solutions rarely existed. Smith graduated from flight training in April 1942, commissioned as a second lieutenant. His final evaluation noted exceptional airmanship and mechanical aptitude, but questioned whether he possessed the aggressive spirit necessary for fighter combat.

The evaluator, a Naval Academy graduate, apparently believed farm boys lacked killer instinct. Smith was assigned to Marine Fighting Squadron 223, VMF223, forming at Iwa Field, Hawaii. The squadron would fly the Grumman F4F Wildcat, a stubby barrel-shaped fighter that looked like a bathtub with wings compared to the sleek Japanese Zero. The Wildcat was slower than the Zero.

It climbed slower, turned slower, and carried less ammunition. On paper, it was inferior in every performance category. But it had two critical advantages: rugged construction that could absorb tremendous damage and 650 caliber machine guns that delivered devastating firepower. Smith studied the Wildcat obsessively.

He flew it to its limits, understanding exactly what it could and couldn’t do. He read intelligence reports about zero capabilities. He talked to pilots who’d survived encounters with Japanese fighters, and he began developing tactics that would exploit American strengths while negating Japanese advantages. His squadron mates watched this with amusement.

The farm boy was trying to reinvent fighter combat. How precious. Everyone knew the way to fight was traditional dog fighting. Turning and burning, getting on the enemy’s tail and shooting him down. That’s what they had been taught at Pensacola. That’s what the manuals said. Smith understood that dogfighting zeros in a wildcat was suicide.

The zero would outturn you every time. But what if you didn’t dog fight? What if you use the Wildcat’s strengths, its ruggedness, and firepower in ways the Japanese didn’t expect? Guadal Canal, Crucible of Fire. August 7th, 1942. American forces landed on Guadal Canal, beginning the first major Allied offensive in the Pacific.

The captured Japanese airfield, renamed Henderson Field, became the most contested piece of real estate in the world. Control of that airirst strip would determine control of the entire Solomon Islands campaign. VMF223 arrived at Henderson Field on August 20th aboard the escort carrier Long Island. 19 Wildcats and 19 pilots landed on a runway made of pierced steel planking surrounded by jungle. Japanese bombers attacked daily.

Japanese warships shelled nightly. Supplies were minimal. Maintenance was primitive. Fuel was rationed. ammunition was limited. This was where the farm boy’s background became advantage. While academy graduates complained about primitive conditions, Smith felt at home. He’d worked with inadequate resources his entire life.

Henderson Field was just another poorly equipped farm that needed to produce results anyway. The squadron commander, Major John El Mangram, quickly recognized Smith’s practical abilities. Within days, Smith was essentially running maintenance operations, teaching mechanics how to repair battle damaged aircraft using improvised parts and creative solutions.

But Smith’s real contribution would come in the air. On August 21st, the day after arrival, Japanese bombers escorted by Zero Fighters attacked Henderson Field. VMF223 scrambled to intercept. This would be Smith’s first combat mission, his first test against the feared zero fighters. What happened next shocked everyone who dismissed the Oklahoma farm boy.

As the Japanese formation approached, most American pilots prepared for traditional dog fights. Smith had other ideas. He’d studied the engagement geometry carefully. The Wildcat couldn’t outturn a zero, but it could dive faster. It couldn’t climb with a zero, but it was much more rugged.

And most critically, the Wildcat’s 650 caliber guns could destroy a zero with a 1second burst, while the Zero’s lighter weapons required sustained fire to kill a Wildcat. Smith’s tactic was brutally simple. Don’t dogfight. Use altitude advantage to dive on zeros at high speed. Fire a quick burst, then use diving speed to escape before the zero could react. Never try to turn with them. Never get slow. Attack from above.

Shoot. Dive away. Climb back to altitude. Repeat. This was called boom and zoom tactics. Though Smith didn’t know the formal term, he’d figured it out through practical analysis. The same way he’d figured out how to get maximum yield from marginal farmland. Use your strengths. Avoid your weaknesses. Don’t fight the enemy on his terms.

On that first mission, Smith dove on a zero from 6,000 ft above. His speed in the dive exceeded 400 mph, too fast for the Zero to evade. He fired a 2-cond burst from 200 yards. The Zero’s fuel tank, unprotected by armor or self-sealing systems, exploded. The Japanese pilot never knew what hit him. Smith didn’t celebrate.

He immediately dove away, building speed, then climbed back to altitude. Two more zeros fell to identical attacks over the next 15 minutes. Smith landed with three kills and a wildcat that had taken only minor damage. The farm kid had just become an ace in a single mission. The reaction from his squadron mates was stunned to disbelief.

How had he made it look so easy? The Zeros were supposed to be superior fighters. Yet Smith had destroyed three of them without engaging in a single traditional turning fight. That evening, Smith explained his tactics to the other pilots. Don’t try to dogfight Zeros, you’ll lose. Instead, use altitude and speed. Dive, shoot, escape. Never get slow.

Never turn with them. Use the Wildcat’s advantages, ruggedness, and firepower. and avoid its disadvantages in maneuverability. Some pilots got it immediately. Others, particularly the Naval Academy graduates, resisted. This wasn’t proper fighter combat. It wasn’t sporting. It was running away.

Real fighter pilots engaged in turning fights and proved their superiority through skill. Major Mangram settled the argument. Smith’s way works. Everyone will fly using his tactics. That’s an order. The Thatche and Tactical Revolution, while Smith was developing boom and zoom tactics independently at Guadal Canal, Lieutenant Commander John S.

Thatch had developed complimentary tactics based on similar principles. Thatch, a Naval Academy graduate and experienced fighter pilot, had reached the same conclusions through different means. That understood that individual wildcats couldn’t dogfight zeros successfully. But what if wildcats worked in pairs, covering each other using coordinated maneuvers? He developed what became known as the thatch weave, a defensive tactic where two wildcats flew in formation, weaving back and forth. When a zero attacked one wildcat, it would fly into the guns of

the other. Smith learned about the thatch weave from Navy pilots also stationed at Henderson Field. He immediately recognized its value and began teaching it to VMF223. Combined with his boom and zoom attacks, it gave Wildcat pilots both offensive and defensive solutions against superior Japanese fighters. The real breakthrough came when Smith combined these tactics with another farm boy insight.

Numbers matter. The Japanese fought with individual brilliance. American pilots should fight as a team. Smith organized his squadron into divisions of four aircraft, two pairs flying the thatchwave. These divisions would attack together, supporting each other, creating multiple threats the Japanese had to respond to simultaneously.

One wildcat might be bait, drawing zeros into turning fights while three others dove from above. This was agricultural thinking applied to aerial combat. On a farm, you don’t try to outwork the weather or the soil. You work with other farmers, share equipment, coordinate efforts, achieve through cooperation what you can’t achieve alone.

Japanese fighter tactics rooted in samurai tradition emphasized individual skill and personal honor. Pilots sought oneon-one duels to prove their superiority. Smith’s tactics made individual skill irrelevant by ensuring Japanese pilots never faced Americans one- on-one. The results were immediate and devastating.

In the week following Smith’s first combat mission, VMF 223 shot down 23 Japanese aircraft while losing only two Wildcats. The loss ratio nearly 12:1 shocked Japanese commanders who’d become accustomed to easy victories. Admiral Yamamoto Earoku, commander of the combined fleet, received reports of the new American tactics with concern.

His diary entry from August 29th noted that American fighters at Guadal Canal have changed their methods. They no longer engage in traditional combat. They attack from altitude with surprise, then disengage before our pilots can respond. Our superiority and maneuverability is being negated. Japanese pilots complained bitterly about American cowardice.

The Americans wouldn’t fight honorably. They attacked from above and ran away. They refused to engage in proper dog fights. This was not warrior behavior. Smith’s response, when told of Japanese complaints, was pragmatic. I’m not here to fight honorably. I’m here to win. Dead heroes don’t help anyone. This attitude, crude by Naval Academy standards, reflected farm boy practicality.

On a farm, you didn’t plant crops in the way that looked most elegant. You planted in the way that produced the most yield. Combat was no different. If you haven’t subscribed yet, you’re missing out on stories like this one. Real history about real people who changed the world, not through privilege or prestige, but through practical wisdom and courage.

Hit that subscribe button right now because what happens next in John Smith’s story gets even more incredible. We’re just getting started. September 1942, the perfect mission. September 9th, 1942 began like most days at Henderson Field. Japanese bombers would attack around noon, escorted by Zeros. American fighters would intercept.

Both sides would lose aircraft. The grinding attrition would continue, but this day would be different. Smith had been promoted to captain and given command of VMF223 after Major Mangram was wounded. Now he could implement his tactical ideas fully without resistance from skeptical senior officers.

At 11:30 hours, coast watchers reported Japanese bombers approaching from Rabal. 27 Betty bombers escorted by 18 zeros. VMF 223 and VMF 224 scrambled 24 Wildcats total to intercept. Smith led his squadron to 25,000 ft, 5,000 ft above the expected Japanese altitude. The other squadron took position at 20,000 ft.

When the Japanese formation appeared at 20,000 ft, Smith’s pilots held position, resisting the natural urge to dive immediately. This was pure farm boy patience. Don’t harvest until the crop is ripe. Don’t attack until the geometry is perfect. Wait for the right moment, even when every instinct screams to act. The Japanese bombers began their attack run on Henderson Field.

The Zero escorts, seeing American fighters above, climbed to engage. This was exactly what Smith wanted. Zero’s climbing meant Zer’s losing energy, becoming slower and less maneuverable. At the perfect moment, Smith led his division into a vertical dive. Four wild cats diving from 25,000 ft reached speeds exceeding 450 mph.

The Zeros, still climbing, had no chance to evade. Smith’s first burst destroyed a zero before the Japanese pilot even knew he was under attack. His wingman got another. The second element got two more. Four zeros down in the opening 10 seconds. The surviving zeros tried to turn into the attack, but the Wildcats were already gone. diving past them at speeds the Zeros couldn’t match.

By the time Japanese pilots reversed course, the Wildcats were 3,000 ft below, extending away, building separation. Meanwhile, the second American squadron dove on the now unescorted bombers. The Betty bombers, designed for range rather than protection, had virtually no armor and unprotected fuel tanks.

They were flying Zippo lighters, waiting for a spark. In the space of four minutes, 11 Betty bombers were destroyed. Seven more were damaged and would crash before reaching Rabal. Of 27 bombers, only nine returned to base. The Zero Escort lost nine fighters. Not a single American fighter was shot down. Smith landed at Henderson Field with his sixth and seventh kills.

But the real victory wasn’t his personal score. It was the demonstration that his tactics, when executed properly, could achieve overwhelming results against supposedly superior enemy forces. The mission report forwarded to Admiral Chester Nimttz at Pacific Fleet Headquarters created immediate interest. Here was proof that American fighters could dominate Japanese fighters despite equipment disadvantages.

The key was tactics, leadership, and fighting as a coordinated team rather than as individual glory seekers. Nimttz ordered Smith’s tactical manual to be distributed fleetwide. Within weeks, Navy and Marine fighter squadrons throughout the Pacific were adopting boom and zoom tactics and division formations.

The era of trying to outdog zeros was ending. The era of fighting smart rather than fighting traditionally had begun. The hidden advantage, mechanical understanding. What most analysts missed about Smith’s success was his deep mechanical knowledge. This wasn’t just about tactics. It was about understanding aircraft performance at a level that formerly trained pilots rarely achieved.

Smith knew from his barnstorming days exactly how engines performed under different conditions. He understood that the Wildcats Pratt and Whitney R1833 radial engine could tolerate abuse that would destroy the Zero’s Nakajima Sakai engine. In a dive, Smith would push the Wildcat past its Redline limitations, achieving speeds the aircraft wasn’t designed for. The rugged American radial engine could handle this briefly. The highly tuned Japanese engine couldn’t.

This gave wildcats a critical speed advantage in the attack phase. Similarly, Smith understood fuel management in ways academy pilots didn’t. Flying over Oklahoma farmland, running out of fuel meant crashing in a field and explaining to his father why the airplane was broken. Smith had learned to extract maximum range from minimum fuel through precise throttle management and mixture control.

At Guadal Canal, fuel was critically short. Japanese submarines and air attacks made resupply dangerous. Most pilots landed with fuel gauges showing empty. Smith routinely landed with 5 to 10 minutes of fuel remaining, which in combat situations could mean the difference between getting home and ditching in the ocean.

His mechanical knowledge also made him invaluable for maintenance. Henderson Field had minimal spare parts and no proper repair facilities. Smith’s experience fixing farm equipment and barnstormer planes translated directly to keeping Wildcats flying with improvised repairs. Engine problems that would ground an aircraft at a proper naval air station were fixed at Henderson with parts scavenged from wrecks. Juryrigged solutions and creative mechanical improvisation.

Smith personally supervised repairs that kept VMF 223’s operational rate higher than any other squadron at Guadal Canal. Captain Marian Carl, another Marine ace at Guadal Canal, later wrote that John Smith was the best pure pilot I ever knew. He flew the Wildcat like he’d designed it himself.

He knew exactly what it could do and exactly where the limits were. That knowledge gave him advantages in combat that no amount of gunnery training could match. October 19 42 the cost of success. By October, Smith had become the leading American ace in the Pacific with 16 confirmed kills. He’d flown 57 combat missions in six weeks. His tactical innovations had changed how America fought the air war.

But success had a price. Henderson Field was under constant attack. Japanese bombers struck daily. Japanese warships shelled nightly. Food was minimal. Disease was rampant. Malaria, deni fever, and dysentery hospitalized more pilots than combat did. Smith himself was suffering from malaria and had lost 20 pounds. He was gaunt, exhausted, and running on willpower alone.

Flight surgeons recommended evacuation. Smith refused. His squadron needed him. On October 12th, Smith led a mission against Japanese bombers attacking Henderson Field. He shot down two bombers, bringing his total to 18 kills. But during the engagement, his Wildcat took hits from Azer’s 20 mm cannon.

One shell exploded in the cockpit, showering Smith with shrapnel. Wounded in the shoulder and leg, Smith managed to nurse his damaged wildcat back to Henderson Field. He landed successfully, then passed out from blood loss and fever. When he woke in the field hospital, doctors informed him he was being evacuated. Smith had flown his last combat mission from Guadal Canal.

In 8 weeks, he’d changed aerial warfare in the Pacific, developed tactics that would be used for the rest of the war, and proven that farmboy Common Sense could defeat supposedly superior enemies. His Medal of Honor citation, presented months later, credited him with 16 confirmed kills. The actual number was certainly higher, but Smith had never cared about personal glory.

He cared about winning, about getting his pilots home alive, about achieving objectives with the resources available. Major General Alexander Vandergrift, commanding the First Marine Division at Guadal Canal, wrote to Smith’s parents that your son’s courage and tactical brilliance saved countless American lives. He taught us how to fight an enemy we believed was invincible. The farm boy from Oklahoma became the teacher of admirals.

The mockery remembered. After evacuation from Guadal Canal, Smith returned to the United States in December 1942. He was promoted to major and assigned as an instructor at Marine Corps Air Station El Toro, California. His job was teaching new fighter pilots the tactics he’d developed in combat. The irony wasn’t lost on Smith.

The same people who’d mocked him as a farm kid now wanted him to train their sons and nephews. The Naval Academy graduates who had considered him beneath them now studied his tactical manuals. One incident captured the transformation. In January 1943, Smith was invited to speak at the Naval Academy in Annapolis.

The invitation came from the Department of Aviation requesting that he lecture midshipman on fighter tactics in the Pacific. Smith’s lecture delivered to 300 future naval officers was characteristically blunt. He began by noting that most of you come from privileged backgrounds. You’ve had excellent educations. You speak well. You present well. You look like naval officers should look.

Then he paused. None of that matters in combat. The Zero doesn’t care if you went to Annapolis or Oklahoma State. It doesn’t care if your father is an admiral or a farmer. It will kill you just as dead either way. What matters is understanding your aircraft, understanding the enemy, thinking clearly under pressure, working as a team, using your strengths, and avoiding your weaknesses.

These are simple principles, but implementing them under combat conditions requires discipline and intelligence. Several midshipmen later recalled that lecture as the most important of their academy education. Lieutenant Robert Anderson, who heard Smith speak and later flew Corsaires in the Pacific, said that John Smith taught us humility.

We thought our academy rings made us superior. Smith showed us that results matter more than pedigree. The mockery that Smith had endured during flight training became teaching material. He openly discussed how other cadets had dismissed him as a hick, how instructors had questioned whether a farm boy could become a fighter pilot, how the class system in the military had almost prevented him from contributing.

His point wasn’t to complain about unfair treatment. His point was that organizations that judge people by background rather than ability harm themselves. The Marines almost missed out on one of their best fighter pilots because he didn’t fit the expected profile.

This message resonated in wartime America where millions of farm boys, factory workers, and immigrants were proving their worth in combat. The myth of natural aristocracy, the idea that people from privileged backgrounds were inherently superior, was dying in the Pacific and European battlefields. Smith embodied the democratic ideal that talent and ability were distributed across all social classes.

That a farm kid with practical intelligence could outperform Ivy League graduates with theoretical knowledge. That America’s strength came from tapping talent wherever it existed, not from preserving class hierarchies. The legacy tactics that won the war. Smith’s tactical innovations became standard throughout American naval aviation.

The boom and zoom attacks, the division formations, the emphasis on teamwork over individual glory, all became fundamental to how America fought the air war. By 1944, new pilots were being trained in Smith’s methods before they ever saw combat. The tactical training unit at Naval Air Station Pun, Hawaii, used Smith’s afteraction reports as textbooks.

Every fighter pilot in the Pacific learned the same basic principles Smith had figured out through farm boy common sense. The results were overwhelming. By mid 1944, American fighters were achieving kill ratios of 10:1 or better against Japanese aircraft. The Zero, once feared as invincible, had become a flying coffin. Japanese pilot quality had declined as experienced aviators were killed.

But American tactical superiority would have produced similar results even against Japan’s best pilots. The psychological impact was equally important. American pilots who’d initially feared the Zero learned they could not only fight it, but dominate it. Confidence replaced fear. Aggressive action replaced defensive caution.

The hunted became the hunter. Smith’s influence extended beyond fighter tactics. His emphasis on mechanical knowledge and practical problem solving influenced how the Navy trained all pilots. The assumption that academy graduates made better pilots than enlisted men or reserve officers was permanently shattered.

By war’s end, some of the Navy’s best pilots were former enlisted men who’d worked their way up through ability rather than connections. Some were reserve officers from state universities. Some were farm boys like Smith, who’d learned to fly in civilian programs. The democratization of the officer corps, forced by wartime necessity, became permanent.

Postwar, the Naval Academy remained prestigious, but it was no longer assumed that academy graduates were inherently superior to other officers. Performance mattered more than pedigree. Postwar the quiet hero. Smith survived the war with 19 confirmed kills, making him one of the Marine Corps’s leading aces.

He received the Medal of Honor, the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and numerous other decorations. He was promoted to colonel and commanded several squadrons and air groups, but he never became famous outside military circles. Unlike some aces who wrote memoirs and sought publicity, Smith remained private. He gave few interviews. He attended reunions but didn’t seek spotlight.

He considered his wartime service a job that needed doing, not a source of personal glory. After retiring from the Marine Corps in 1960, Smith returned to Oklahoma. He bought a small cattle ranch and lived quietly, raising cattle the same way his father had. Neighbors knew he was a retired Marine officer, but few knew he was a Medal of Honor recipient and combat ace.

In 1973, a researcher writing a book about Guadal Canal tracked Smith down. The researcher, expecting to find a larger than-l life warrior, instead found a quiet cattleman who seemed more comfortable discussing livestock prices than aerial combat. When asked about his medal of honor, Smith was characteristically modest. A lot of good men died at Guadal Canal.

I survived and got a medal. They died and got buried in jungle graves. I don’t feel particularly heroic. When asked about his tactical innovations, Smith was equally dismissive. I just used common sense. The Wildcat couldn’t dogfight a zero, so I didn’t dogight. That’s not innovation. That’s just not being stupid. But when asked about the class prejudice he’d faced, Smith became more animated.

The military had a real problem looking down on people who didn’t fit their image of what an officer should be. Too many good men were overlooked because they had the wrong accent or wrong background or didn’t go to the right schools. That was stupid and it cost lives.

Before we get to how John Smith’s story ends and what it means for us today, I want to ask you to hit that subscribe button if you haven’t already. This channel exists to tell the stories of people like Smith who changed history not through privilege but through ability and determination.

Every subscription helps us bring you more forgotten heroes and untold stories. Subscribe now and let’s keep learning together. The final accounting. What did John Smith actually accomplish beyond his personal kill record? Beyond his decorations, what was his lasting impact? The most comprehensive analysis came from the Naval Aviation Historical Branch’s 1968 study of fighter tactics in World War II.

The study concluded that Smith’s tactical innovations, widely adopted across naval aviation, increased American fighter effectiveness by approximately 40% while reducing losses by roughly 30%. Translated into human terms, Smith’s tactics probably saved several thousand American pilot lives during the Pacific War.

His emphasis on coordinated teamwork prevented the horrific loss rates that characterized early Pacific fighting where individual American pilots tried to dogfight superior Japanese fighters. The economic impact was significant. Each fighter pilot cost approximately $100,000 to train, roughly $1.5 million in current dollars. Each aircraft cost about $50,000. Smith’s tactics by reducing loss rates saved hundreds of millions in training and equipment costs.

But the real impact was strategic. Smith proved that American pilots and American aircraft could defeat Japanese forces despite technical disadvantages. This proof came at a critical moment when American morale in the Pacific was fragile and Japanese victory seemed possible.

If Guadal Canal had failed, if Japanese fighters had maintained aerial superiority, the entire Pacific campaign might have stalled. Smith’s success demonstrated that Americans could learn, adapt, and overcome challenges that initially seemed insurmountable. The timeless lessons John Smith died on June 4th, 1972 at age 57 from a heart attack while working cattle on his ranch.

His obituary in the Lexington newspaper noted his Medal of Honor, but devoted more space to his community service and ranching activities. Most readers had no idea they’d lost one of World War II’s most important fighter pilots, but Smith’s legacy endures in the lessons his life teaches. These lessons transcend military history and speak to fundamental questions about talent, ability, and social class.

First, talent exists across all social strata. Smith’s abilities weren’t created by privilege or expensive education. They came from practical intelligence, mechanical aptitude, and the kind of problem-solving skills that farm life develops. Organizations that recruit only from elite backgrounds limit their talent pool unnecessarily.

Second, practical experience often beats theoretical knowledge. Smith’s hundreds of hours flying marginal aircraft over Oklahoma farmland taught him more about flying than many pilots learned in formal programs. Hands-on experience, particularly experience dealing with inadequate resources, creates capabilities that classroom learning can’t match.

Third, innovation comes from questioning assumptions. Smith didn’t accept that dog fighting was the only way to fight. He questioned the assumption, analyzed the problem, and developed new solutions. This willingness to challenge conventional wisdom, easier when you’re an outsider who wasn’t indoctrinated into that wisdom, enables breakthrough thinking.

Fourth, results matter more than credentials. Smith’s Medal of Honor and 19 kills didn’t come from his background or training pedigree. They came from effectiveness in combat. Judging people by credentials rather than performance is lazy and counterproductive. Fifth, teamwork multiplies individual ability.

Smith’s tactics emphasized coordinated action over individual glory. This reflected farm culture where neighbors helped each other and cooperation was necessary for success. American military culture influenced by Smith and others like him became more teamoriented and less focused on individual heroics.

These lessons apply far beyond military aviation. Businesses that recruit only from elite universities miss talented people from state schools and community colleges. Organizations that value credentials over demonstrated ability limit their access to talent. Systems that preserve class hierarchies harm themselves by preventing capable people from contributing. Modern relevance.

The story of John Smith resonates today because the tensions he faced still exist. Elite institutions still provide advantages to their graduates. Class background still influences opportunity. Practical experience is still undervalued compared to formal credentials. But Smith’s example proves these barriers aren’t insurmountable. Talent can overcome prejudice.

Ability can defeat privilege. Results can override credentials. The farm boy can become the ace, the innovator, the teacher of admirals. Modern militaries understand this better than they did in 1942. Today’s fighter pilots come from diverse backgrounds. The assumption that academy graduates make better pilots is dead.

Performance in training, not undergraduate institution, determines who flies fighters. But civilian institutions often lag behind. Elite universities still dominate access to prestigious careers. Professional services firms still recruit primarily from a handful of schools. The assumption that pedigree predicts performance persists despite evidence to the contrary.

Smith’s story is a reminder that this assumption is not only wrong but costly. Organizations that judge by background rather than ability missed talented people, they pay more for less capable employees from prestigious schools while overlooking more capable people from ordinary backgrounds.

The challenge is measuring ability rather than credentials. Smith’s ability was proven in combat where results were unambiguous. In civilian life, ability is harder to assess. Credentials become a shortcut, a way to filter candidates without doing the harder work of evaluating actual capability. But shortcuts have costs.

The military that almost rejected Smith would have been weaker without him. The squadrons that benefited from his tactics would have suffered higher losses using conventional methods. Organizations today that reject talented people for lacking proper credentials harm themselves similarly. Conclusion: The Farm Boys vindication. On August 17th, 1942, John Smith was a farm kid whom educated pilots mocked.

By October, he was the leading American ace in the Pacific and the developer of tactics that changed aerial warfare. The transformation took eight weeks and was purchased with courage, intelligence, and farmboy common sense. The men who’d mocked him learned their lesson. Some learned it from his tactical manuals. Some learned it from the kills marked on his wildcat’s fuselage.

Some learned it the hard way, watching Smith succeed where they struggled, realizing that their academy rings and family connections meant nothing at 23,000 ft above Guadal Canal. Smith never gloated about this vindication. He considered it irrelevant. The mission was defeating Japan, not proving farm boys could fly fighters.

Personal vindication was a distraction from that mission. But vindication came anyway, not through Smith’s words, but through his results. 19 confirmed kills, Medal of Honor, tactical innovations that saved thousands of lives. The proof was overwhelming. The farm kid they’d mocked had changed the war. The irony is perfect.

The Naval Academy graduates who dismissed Smith as unqualified ended up studying his tactics. The wealthy pilots who considered him a hick ended up flying using his methods. The instructors who’d questioned whether a farm boy could become a fighter pilot ended up teaching Smith’s techniques to new classes of cadetses. Smith’s response to all of this characteristically was practical rather than bitter.

He didn’t waste energy on resentment about past mistreatment. He focused on teaching what he’d learned so others could benefit. The prejudice he’d faced was stupid and harmful, but dwelling on it accomplished nothing. Moving forward and helping others mattered more. This attitude, this focus on results over grievances, on solutions over complaints, on moving forward rather than looking back was quintessentially American. It was farmboy pragmatism applied to life.

Problems exist. Fix them. Obstacles appear. Overcome them. People doubt you. Prove them wrong through action, not argument. John Smith proved them wrong through 19 kills. Through tactical innovations that changed a war, through leadership that saved thousands of lives.

He proved that privilege predicts nothing. That pedigree means nothing. That credentials guarantee nothing. Ability, determination, and practical intelligence. Those are what matter. The farm boy who learned to fly in an Oklahoma wheat field ended up teaching admirals how to fight. That’s not just a personal success story. That’s proof that American democracy works. That talent exists everywhere.

That given opportunity, people from any background can achieve excellence. They mocked the farm kid pilot until his first mission changed aerial warfare. Then the mockery stopped and the learning began. John Smith taught the United States Navy and Marine Corps how to fight and win in the Pacific.

He did it with tactics developed through farm boy common sense, mechanical knowledge gained from fixing tractors, and courage earned over Oklahoma wheat fields in a decrepit biplane. His legacy isn’t just the tactics that bear his influence. It’s the proof that America’s strength comes from finding talent wherever it exists. From farm fields to fighter cockpits, from wheat country to war zones, from Oklahoma to Guadal Canal.

The farm boy became the ace, the innovator, the teacher, the hero. And in doing so, he proved that in America, anybody can be anything if they’re given a chance and they’re willing to work for it. That’s John Smith’s real legacy. Not the 19 kills or the Medal of Honor, but the demonstration that talent, determination, and practical intelligence can overcome any prejudice, defeat any enemy, change any outcome.

The farm boy they mocked changed history. And in doing so, he reminded America what makes it different, what makes it special, what makes it strong. Not aristocracy, not privilege, not pedigree, but opportunity, ability, results. The farm kid pilot they mocked until his first mission changed aerial warfare. That’s America in one sentence.

That’s democracy in action. That’s the promise that anyone from anywhere can make a difference if they’re given a chance. John Smith proved it over Guadal Canal in 1942. His example proves it

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load