On the frigid morning of December 16th, 1944 at 0630 hours in Manson Shaw, Germany, Hedman Klaus Richer of the 12th SS Panza Division hunched over a frostcovered notebook, pencil scratching furiously as he recorded a scene of devastation unlike anything seen before in the annals of modern warfare. Across the mistladen fields near Hen, an entire German battalion had been annihilated in minutes.

Not by direct artillery hits, nor by conventional time shells requiring precise calculations, but by an almost supernatural force. Shells that detonated automatically 30 ft above the ground, raining lethal fragments over trenches, foxholes, and makeshift cover, transforming soldiers defenses into death traps. In just 3 minutes, 702 men lay dead, and the few survivors returned in shock, murmuring a chilling refrain, “Die Luft taught, “Death comes from the air itself.

” What Richer did not know was that he had just witnessed the combat debut of America’s most closely guarded secret of ground warfare, the Proximity Fuse, a revolutionary device housing a miniature radar system capable of intelligent detonation. the first true smart weapon whose impact would eclipse almost every other military innovation of the war, save for the atomic bomb.

Mathematically, the fuses effect was staggering. Where conventional anti-aircraft shells required over 500 rounds to bring down a single aircraft, proximity fused shells succeeded with only 155. where traditional artillery killed soldiers hiding in trenches 5% of the time, proximity fuses inflicted 70% casualties, and where London’s survival against the onslaught of V one flying bomb seemed improbable, proximity fuse defenses destroyed nearly 79% of incoming missiles within weeks, preserving lives and infrastructure

alike. The journey of this extraordinary invention began not in American laboratories but in the shadow of Britain’s darkest hour. On October 30th, 1939 in Exat, England, a young scientist named W. But working with colleagues Edward Sh and Amherst Thompson at the air defense establishment proposed an idea that seemed like pure science fiction, an artillery shell that could think.

He reasoned that the First World War’s failure rates for anti-aircraft artillery, averaging 8,500 shells per plane destroyed, would only worsen with faster, higher flying aircraft, and that Britain’s very survival depended on a radical solution. His concept relied on using radio waves to detect approaching aircraft and trigger automatic detonation at the optimal altitude.

A feat that required electronics capable of surviving forces exceeding 20,000 times gravity, spins of 30,000 revolutions per minute, and extreme temperature ranges from minus50 to plus 100° F. Initial tests with unrotated projectiles proved the idea feasible, but the limitations of British industry made mass production impossible.

In September 1940, the desperate solution arrived via the historic Tizzard mission. Britain’s top scientific secrets, including the proximity fuse, were delivered to the United States aboard the Canadian Pacific Liner Duchess of Richmond. Arriving in Washington, the delegation briefed American officials, culminating in a pivotal meeting on September 19th when Dr.

John Cochraftoft introduced the concept to 39-year-old American physicist Merl A. Tvite, recently appointed to lead section T of the National Defense Research Committee. Tvet, a rural South Dakota native who had grown up tinkering with radios alongside future Nobel laurate Ernest Lawrence, had recently been galvanized by reports of the London Blitz to find a technological solution to save lives.

With the British concept now in hand, TV faced the colossal challenge of converting theory into a working mass-producible weapon capable of enduring the extreme conditions of artillery fire. By December 1940, a mansion at 5241 Broad Branch Road, Washington had become the nerf center of the project where Tvite assembled a team of elite scientists Richard B. Roberts, Henry H.

Porter, Robert B. Broad, Lawrence Haad, Lloyd Burkner, and James Van Allen among others. Van Allen’s task was to develop vacuum tubes capable of withstanding extreme G-forces. A problem he solved by borrowing techniques from hearing aid manufacturer and inventing the ingenious mousetrap spring system, protecting filaments during launch and releasing them in flight.

Burkner developed a circuit configuration allowing greater detection distances and reliability. and the National Carbon Company created a revolutionary reserve battery system, shattering amp pools that activated mid-flight to power the system. The fuse incorporated a complete radar system in a mere 5-in shell, including transmitter, receiver, amplifier, detonator, and safety mechanisms, operating on frequencies previously thought cutting edge, achieving the impossible through elegant autodine design.

By March 1942, the applied physics laboratory at John’s Hopkins University became the hub for development. A converted Chevrolet dealership housing the most advanced electronics lab in the world with a culture that prioritized speed, precision, and moral responsibility above all. Combat testing began at sea and in the Pacific.

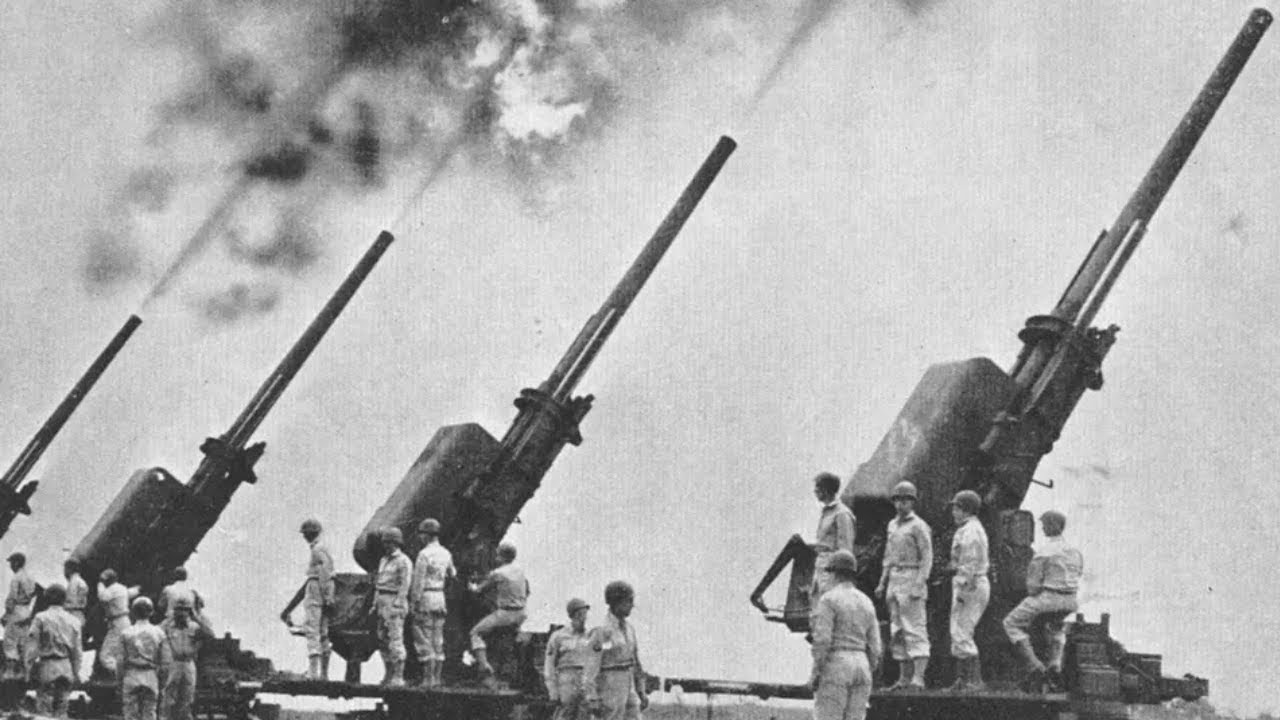

On January 5th, 1943, USS Helena’s radar detected four incoming Japanese dive bombers with proximity fused shells loaded and ready. The first salvo passed close to its target and then in a moment witnessed by stunned gunners. One shell detonated midair, sending a perfect sphere of lethal fragments across the aircraft, shearing wings and igniting engines.

Over the coming months, proximity fused shells transformed naval warfare, giving the US Navy near miraculous anti-aircraft capability. Test results from USS Cleveland’s trials with drone aircraft had already convinced the Navy to commit fully to mass production. By 1943, the first thousands of shells were distributed across the Pacific Fleet.

Crews marveled at the new weapon, realizing that the shells themselves were thinking dramatically increasing kill rates while reducing the need for near impossible marksmanship. The psychological impact was profound with sailors feeling empowered, almost invincible as the enemy’s aircraft fell from the sky in unprecedented numbers.

In Europe, the impact was equally transformative. During the defense of London against V1 flying bombs, proximityfused shells coupled with radar directed gun systems raised interception success rates from 24% to nearly 80% within weeks. In Antworp, the shells safeguarded vital supply lines, neutralizing nearly all incoming missiles and allowing Allied armies to advance unimpeded into Germany.

During the Battle of the Bulge, the first use of proximityfused shells in ground combat obliterated German infantry advancing across open fields, delivering thousands of casualties in minutes, shattering morale and rendering traditional tactics obsolete. General Patton, witnessing the results firsthand, recognized that armies would need entirely new strategies once such weapons became universal.

The industrial mobilization behind the fuse was equally extraordinary. Converted bakeries, automobile garages, and Christmas light factories produced the world’s first mass-produced smart weapon, employing tens of thousands of workers across more than 100 factories, assembling over 22 million units by war’s end.

Precision components, miniature vacuum tubes, and batteries had to be flawless. Each failure could prove fatal to American soldiers. Secrecy rivaled the Manhattan project with workers unaware of the true nature of their labor. Employees addressed as doctor regardless of rank and even captured fuses examined by German scientists dismissed as impossible.

Germany and Japan attempted similar technologies, but failed due to industrial limitations, fragmented research, and lack of mass production capability, leaving the allies with an unassalable technological advantage. The human dimension of the Fuses story is no less compelling. Scientists like Van Allen and Tvit saw their work save lives directly in combat.

Sailors like Lieutenant Cochran witnessed the transformation firsthand, and assembly workers like Betty Thompson discovered decades later the miraculous weapon they had helped construct. The proximity fuse reshaped the Pacific War, making kamicazi attacks survivable, decimating Japanese carrier aviation and saving thousands of lives.

In Europe, it turned the tide during the Arden offensive, protected vital cities and supply hubs, and rendered centuries of military doctrine obsolete. Leaders from Eisenhower to Churchill recognized its decisive impact, estimating that without proximityfused munitions, Allied casualties, lost ships, and civilian deaths would have been exponentially higher.

Post war, even German military leaders acknowledged that their traditional defenses had been rendered irrelevant overnight by the fuse. A testament to the transformative power of American innovation, industrial capacity, and the genius of science applied to survival. In every theater, from the frostcovered fields of Germany to the stormtossed waters of the Pacific and the skies above London, the proximity fuse redefined warfare, proving that a single technological breakthrough when combined with vision, ingenuity, and industrial might could

save lives, destroy the enemy, and change the course of History

News

Inside Willow Run Night Shift: How 4,000 Black Workers Built B-24 Sections in Secret Hangar DT

At 11:47 p.m. on February 14th, 1943, the night shift bell rang across Willow Run. The sound cut through frozen…

The $16 Gun America Never Took Seriously — Until It Outlived Them All DT

The $16 gun America never took seriously until it outlived them all. December 24th, 1944. Bastonia, Belgium. The frozen forest…

Inside Seneca Shipyards: How 6,700 Farmhands Built 157 LSTs in 18 Months — Carried Patton DT

At 0514 a.m. on April 22nd, 1942, the first shift arrived at a construction site that didn’t exist three months…

German Engineers Opened a Half-Track and Found America’s Secret DT

March 18th, 1944, near the shattered outskirts of Anzio, Italy, a German recovery unit dragged an intact American halftrack into…

They Called the Angle Impossible — Until His Rifle Cleared 34 Italians From the Ridge DT

At 11:47 a.m. on October 23rd, 1942, Corporal Daniel Danny Kak pressed his cheek against the stock of his Springfield…

The Trinity Gadget’s Secret: How 32 Explosive Lenses Changed WWII DT

July 13th, 1945. Late evening, Macdonald Ranchhouse, New Mexico. George Kistakowski kneels on the wooden floor, his hands trembling, not…

End of content

No more pages to load