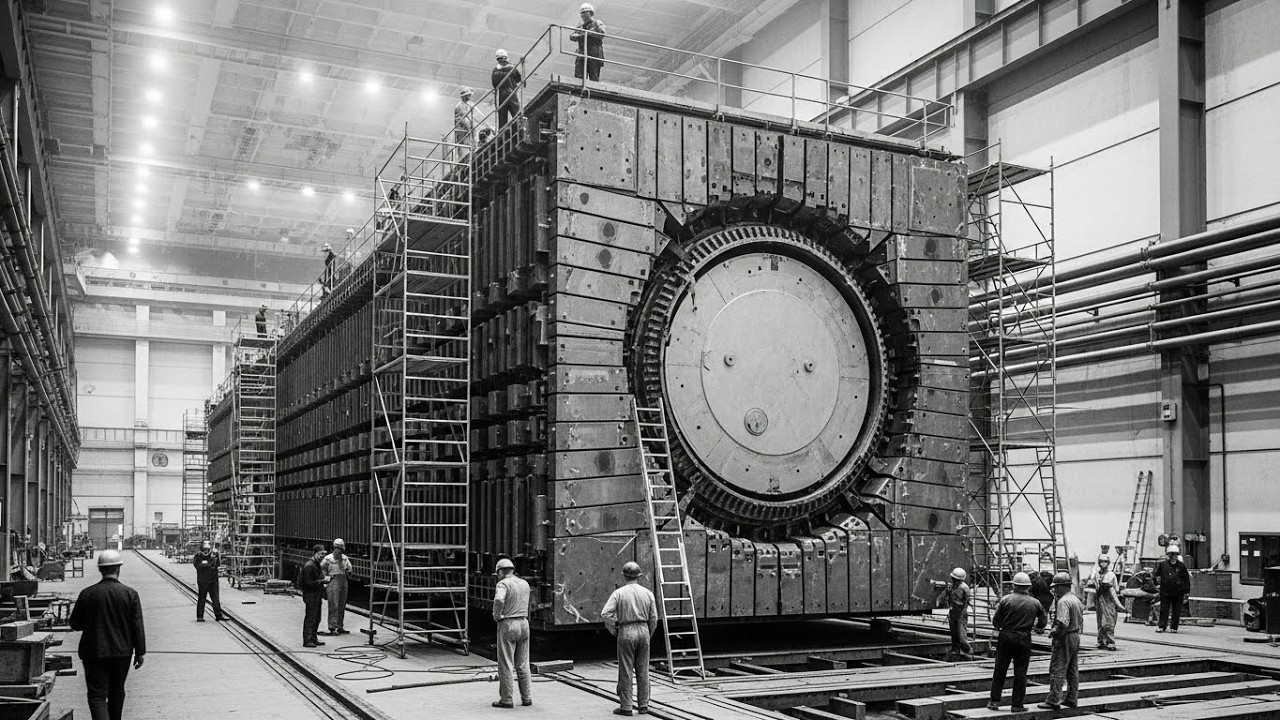

September 26th, 1944, 10:48 p.m. Hanford, Washington. Inside a massive concrete structure along the Colombia River, something unprecedented was about to happen. A graphite cube measuring 28 ft wide, 36 ft long, and approximately 40 ft high sat ready for activation. 1,200 tons of pure graphite stacked block by precisely machined block.

Penetrating through its entire depth were 2004 aluminum tubes loaded with uranium fuel. This wasn’t a bomb. This was a factory. A factory designed to manufacture something that had never existed in measurable quantities on Earth. Plutonium 239. The Manhattan project had a uranium bomb design.

Scientists were confident about that. But uranium 235 was extraordinarily rare, requiring massive enrichment facilities that might take years to produce enough material for even a handful of weapons. They needed an alternative. They needed plutonium. The problem? In 1942, the entire world’s supply of plutonium could fit on the head of a pin.

Nobody had ever manufactured it in visible quantities. Nobody knew if it could actually detonate in a weapon, and nobody had any idea how to produce it at industrial scale. The solution required building something never attempted, a production nuclear reactor. Not a small experimental pile like Enrio Ferm’s successful test in Chicago, but an industrial scale machine capable of breeding plutonium atoms while simultaneously preventing catastrophic meltdown.

This is the story of how engineers solved an impossible problem with 1,200 tons of graphite blocks, 2004 aluminum tubes, and a cooling system that pumped 75,000 gallons of Columbia River water every single minute. This is the story of the B reactor at Hanford. To understand why this graphite cube was necessary, we need to understand what plutonium actually is and why it was so difficult to create.

Plutonium 239 doesn’t exist naturally in any significant quantity. When uranium 238, the most common uranium isotope, absorbs a neutron, it transforms through radioactive decay into neptunium 237, which then decays into plutonium 239. This process takes days, not the millions of years required for natural radioactive decay. Here’s the challenge.

You need uranium 238 to absorb neutrons. But to get those neutrons, you need a sustained nuclear chain reaction. And maintaining that reaction while controlling temperature, preventing meltdown, and actually extracting the plutonium afterward requires engineering on a scale never attempted. Lieutenant Colonel Matias Matias received his orders in December 1942.

find a location to build three massive nuclear reactors. The requirements seemed contradictory. The site needed to be remote enough that a potential accident wouldn’t threaten major population centers. It needed unlimited water for cooling. It needed reliable electricity. It needed to be flat enough to construct massive industrial facilities.

and it needed to be far enough from any coast where enemy aircraft or saboturs might reach it. Matias and two Dupont engineers evaluated sites across Montana, Oregon, California, and Washington. On December 22nd, 1942, flying over a barren stretch of land along the Columbia River in South Central Washington, Matias found what he was looking for. The area was isolated.

Tumble weeds outnumbered people. The Columbia River provided essentially unlimited water. Grand Koulie Dam supplied reliable electricity and the nearest significant city, Seattle, was 200 m away. On December 31st, 1942, Matias and his team unanimously recommended the Hanford site. General Leslie Groves approved the selection on January 7th, 1943.

But acquiring the land meant displacing people who had lived there for generations. About 1,500 residents of the towns of Hanford and White Bluffs along with members of the Wanapam people and other Native American tribes received eviction notices in early 1943. They were given 30 days to evacuate their homes and abandon their farms.

The government offered minimal compensation and no explanation for why their land was needed. By March 1943, construction began. Within weeks, 45,000 construction workers descended on the desert. They built not just reactors but an entire industrial complex, chemical separation plants, worker housing, roads, rail lines, and power infrastructure.

But what nobody fully understood yet was that designing and building the reactor would reveal problems that no calculation could predict. The B reactor’s design came from physicist Eugene Vner and a team of DuPont engineers led by Crawford Greenowalt. This combination proved essential. Vignner provided theoretical physics expertise while DuPant brought decades of experience building large-scale industrial chemical facilities.

The fundamental challenge was this. Uranium fuel needed to be close enough together that neutrons from one fishision reaction could trigger fision in neighboring fuel, creating a sustained chain reaction. But the fuel also needed to be spaced far enough apart that the reaction could be controlled and moderated.

The solution was the graphite cube. Graphite, pure carbon arranged in crystalline form, had a unique property discovered through earlier experiments. It slowed down fast-moving neutrons without absorbing them. Slow neutrons were much more likely to cause fision in uranium 235 or to be absorbed by uranium 238 to create plutonium 239. The graphite would act as a moderator, controlling the reaction while allowing it to continue.

The design called for stacking graphite blocks to create a cube approximately 28 ft wide, 36 ft at the base, and 40 ft high. Through this cube, 2004 horizontal holes would be drilled from front to back. Aluminum tubes would be inserted through these holes. Inside the tubes, cylindrical uranium fuel slugs encased in aluminum cladding would be loaded.

approximately 32 slugs per tube. Water from the Colombia River would flow through the tubes, cooling the uranium while the nuclear reaction proceeded. Eugene Vner and the Met Lab team suggested water cooling and Dupant engineers concurred that water was the best option given all the engineering constraints.

The cooling system would need to pump 75,000 gall per minute through the reactor. water consumption approaching that of a city of 330,000 people. Here’s where the engineering became extraordinarily difficult. The graphite blocks had to be machined to tolerances of plus or minus 0.005 in 5,000 of an inch. Why such precision? Because any gaps between blocks would allow neutrons to escape, potentially stopping the chain reaction.

The blocks also had to be absolutely pure. Even tiny amounts of impurities like boron would absorb neutrons and poison the reaction. The specifications for the graphite were unprecedented. Dupant contracted with Spear Carbon Company and National Carbon Company to produce graphite blocks of purity never before demanded from the world’s few graphite manufacturers.

The manufacturing process required heating petroleum coke to approximately 2700° C in specialized furnaces, then machining each block to exact specifications. The graphite blocks came in standard dimensions 4 and 3/16 in square by 48 in long, though specialized shapes were required to accommodate the tube channels and control rod passages.

The pile required 2,000 tons of machined graphite blocks bored to permit installation of the 2004 aluminum tubes. Each block had to be tested for purity using neutron absorption measurements. Blocks showing even slight neutron absorption were rejected. The reactor core would be surrounded by a biological shield, a massive concrete structure 7 ft thick designed to absorb radiation and protect workers.

This shield would be enclosed in a steel containment structure measuring 46 ft on each side and standing 41 ft high. But the biggest challenge was still ahead. Controlling a chain reaction that left unchecked would destroy itself in seconds. A nuclear chain reaction once started doesn’t want to stop. Neutrons split uranium atoms, releasing more neutrons, which split more atoms, releasing even more neutrons.

Without control, the reaction would accelerate exponentially toward meltdown. Within seconds, the B- reactor’s control system used three different mechanisms, each serving as a backup to the others. First, nine horizontal control rods made of boron steel could be inserted into channels running perpendicular to the fuel tubes.

Boron absorbs neutrons extremely efficiently. Push the rods in and the reaction slows or stops. Pull them out and the reaction accelerates. During operation, these rods would be positioned to maintain steady controlled reaction rates. The horizontal rods were approximately 20 ft long and moved on electric drives controlled from the central control room.

Operators could adjust rod position in small increments, allowing precise control over reaction rate. Second, 29 vertical safety rods could drop into channels through the top of the reactor. These were the emergency system. If anything went wrong, if the reaction started accelerating too quickly, operators could release these rods, which would drop by gravity into the core within 2 seconds, flooding the reactor with neutronabsorbing material and stopping the reaction immediately.

Third, as a final backup, the entire reactor could be drowned by injecting a solution of cadmium salts into special channels. This was the absolute last resort because flooding the reactor with cadmium solution would essentially poison it permanently. The control room located in a shielded building adjacent to the reactor featured instruments that would look familiar to modern nuclear operators.

Dials displayed neutron flux levels at various positions within the core. Temperature gauges tracked cooling water temperatures. Chart recorders continuously documented the reaction rate, creating permanent records of reactor operation. The cooling system was equally sophisticated. River water entered the reactor through large diameter supply pipes.

Electric pumps forced water through distribution manifolds feeding the 2004 process tubes. The water entered at approximately 20° C and exited at temperatures approaching 95° C, carrying away enormous heat generated by nuclear fision. Construction of the graphite core began in March 1944. Workers, most of whom had no idea they were building a nuclear reactor, stacked blocks according to precise blueprints under the official cover story of a pilot plant for a new chemical process.

Security was intense. Armed guards patrolled constantly. Workers were segregated by task so that no individual understood the complete system. The work proceeded 24 hours a day. Each layer of graphite had to be surveyed and measured before the next layer began. By late August 1944, the graphite core was complete and the 2004 aluminum process tubes were installed.

On September 13th, 1944, under the personal supervision of Enrico Fermy, workers began loading uranium fuel slugs into the reactor. Each slug weighed approximately 8 lb. Loading proceeded carefully over the next several days. On the evening of September 26th, 1944, the moment of truth arrived. Present for the startup were some of the most distinguished scientists of the Manhattan project.

Enrio Fairmy, Eugene Wagner who headed the reactor design team, John Marshall from FM’s staff, John Wheeler, and Crawford Greenowalt, Dupant’s technical director for the Manhattan project. The startup sequence began cautiously around 11 p.m. Control rods slowly withdrew from the core. Neutron detectors registered increasing activity.

The chain reaction was beginning. At exactly 10:48 p.m. on September 26th, 1944, the B reactor achieved criticality, a self- sustaining nuclear chain reaction. Less than 2 years after Ferm’s experimental demonstration in Chicago, an industrialcale reactor had successfully started. Over the next several hours, operators gradually increased power by withdrawing control rods further.

By midnight, the reactor was producing several megawatts of thermal power. Everything appeared to be working perfectly. The graphite core maintained structural integrity despite rising temperatures. The cooling water system functioned flawlessly, pumping 75,000 gall per minute through the 2004 tubes. By early morning on September 27th, power output had increased substantially.

Engineers were jubilant. The reactor was working. Crawford Greenowalt, DuPont’s project director, remained in the control room monitoring progress. Then something impossible happened. The reaction began to slow down. Without any change in control rod position, neutron flux levels started dropping. Within hours, the chain reaction had stopped completely.

Operators withdrew control rods further, trying to restart the reaction. It worked for a few hours. Then the reaction faded again. Something was poisoning the reactor, absorbing neutrons and stopping the chain reaction. Greenalt stayed at the reactor until 2:00 in the morning working on solving the mystery. The problem was xenon 135 poisoning.

John Wheeler, a young physicist who had worked on the reactor design, had predicted this possibility. During the design phase, he had insisted on adding 504 extra tube channels beyond what calculations indicated were necessary. DuPont engineers had questioned the additional expense, but Wheeler had been adamant.

There were too many unknowns in nuclear physics and they needed safety margin. Now his caution proved essential. Wheeler suspected xenon 135, a fision product that absorbs neutrons extremely efficiently. When the reactor operates, it produces xenon 135, but xenon 135 has a half-life of only 9.2 hours. Wheeler theorized that during operation, xenon 135 builds up to an equilibrium level, where production equals decay.

When the reactor shuts down, xenon 135 continues being produced from decay of other fision products, particularly iodine 135, but it’s no longer being burned up by neutrons. The concentration increases dramatically, poisoning the reactor. The solution was to load more uranium fuel into those extra tube channels Wheeler had insisted on.

More uranium meant more fision reactions, producing more neutrons, enough to overcome the xenon 135 absorption. Over the next 48 hours, workers loaded additional tube fuels. By September 29th, with the additional fuel loaded, the reactor restarted and climbed steadily toward full power. By February 1945, the B- reactor reached its designed full power output of 250 megawatt thermal.

It was producing significant quantities of plutonium 239. But what nobody yet knew was that the xenon crisis would reveal something profound about engineering under uncertainty. Once the B- reactor achieved stable operation at 250 megaww, it ran continuously for months at a time.

But breeding plutonium was only half the challenge. The uranium fuel had to be periodically removed and the plutonium chemically extracted through a process nearly as dangerous as the reactor itself. The fuel loading system was designed for remote operation. Workers stood on a platform at the front face of the reactor, protected by massive water- fil shields and thick concrete barriers.

Using long poles with specialized grips, they could push fresh uranium slugs into the front of a tube. As new slugs entered, irradiated slugs that had spent months absorbing neutrons in the reactor core were pushed out the rear, dropping into a water-filled canal 40 ft deep. These irradiated slugs were intensely radioactive. Direct exposure would deliver a lethal dose in seconds.

The slugs remained underwater in cooling canals for several weeks while the most intense short-lived radioactivity decayed. After cooling, the slugs were loaded into heavily shielded casks and transported to chemical separation facilities several miles away. Massive plants with code designations T plant and Bplant. There through one of the most complex chemical processes ever attempted on industrial scale the plutonium was chemically separated from uranium and fision products.

The separation process dissolved fuel in boiling nitric acid then used a series of chemical extraction steps to isolate plutonium. The entire operation had to be conducted remotely using robotic manipulators viewed through thick leaded glass windows because entering the processing cells would be immediately fail. By February 1945, just five months after achieving full power, the B reactor and its two sister reactors D reactor and F reactor, which started up on December 17th, 1944 and February 15th, 1945, respectively, were producing plutonium at rates sufficient

to manufacture multiple bomb cores. All three reactors were running at full 250 megawatt power by March 8th, 1945. By April, kilogram quantity amounts of plutonium were being delivered to Los Alamos, New Mexico, where it was fabricated into bomb cores. The first plutonium bomb tested at Trinity site on July 16th, 1945 contained Hanford plutonium.

Three weeks later on August 9th, 1945, a second Hanford produced plutonium bomb was detonated over Nagasaki, Japan. The war in the Pacific ended 6 days later. The B reactor operated continuously until 1968, producing plutonium for 24 years. During that time, it established fundamental design principles for all subsequent production reactors built by the United States, Soviet Union, United Kingdom, France, and China.

The engineering innovations developed at Hanford profoundly influenced civilian nuclear power. The concept of using water as both coolant and means of controlling reaction rate became standard in most commercial power reactors. The control rod systems, backup safety mechanisms, and remote handling technology all evolved from Hanford’s original designs.

The reactor was graphite moderated and water cooled using an open cycle directly with the Columbia River. Initial water flow was approximately 27,000 gall per minute, later increased to 75,000 gall per minute at full power operations. Engineers calculated that even a 1 minute interruption of continuous water flow would cause the graphite to overheat catastrophically.

But the B- reactor’s legacy is complicated. The plutonium it produced enabled nuclear weapons that ended World War II, but also initiated the Cold War arms race. Between 1945 and 1968, Hanford’s nine production reactors created plutonium for more than 60,000 nuclear weapons. The environmental consequences were severe.

Radioactive waste generated during plutonium production remains stored at Hanford, representing one of the most significant environmental remediation challenges in American history. The site contains 56 million gallons of radioactive and chemical waste stored in 177 underground tanks. Cleanup efforts began in 1989 and continue today with full site remediation projected to continue until60 at a cost exceeding $100 billion.

Today, the B reactor is preserved as a national historic landmark and part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park. It’s the only Manhattan Project reactor accessible to the public through guided tours. The reactor building is remarkably well preserved. The graphite core remains in place, still structurally sound after 80 years.

The control room retains its original instruments. The neutron flux dials, temperature recorders, control rod position indicators all remain as they were when the reactor produced the plutonium that changed history. A clock in the control room is stopped at 10:48 p.m. The moment on September 26th, 1944, when the B reactor went critical as the world’s first full-scale plutonium production reactor.

The real lesson from the B reactor isn’t about nuclear weapons or even nuclear power. It’s about engineering under impossible constraints with incomplete knowledge. A team of physicists and engineers working with limited understanding of nuclear physics built a machine that had never existed before. They used materials manufactured to unprecedented purity, operated at scales never attempted, and solved problems they couldn’t predict in advance.

They succeeded because they built in redundancy. John Wheeler’s insistence on 504 extra fuel channels saved the entire project when xenon poisoning appeared. Without that design margin, the B- reactor would have been a $150 million failure, unable to overcome the neutron absorption of xenon 135. They succeeded because they combined theoretical understanding with practical engineering experience.

Eugene Wignner provided physics expertise. Crawford Greenwalt and the Dupant team provided industrial know-how. Neither group alone could have succeeded. They succeeded because they acknowledged uncertainty and planned for unknown challenges. The design included safety margins far beyond what calculations suggested were necessary.

Multiple redundant safety systems protected against failures. The containment structures were massively overengineered. Every one of these precautions proved necessary when unexpected problems emerged. The 1200 ton graphite cube represented more than just a nuclear reactor. It represented a fundamentally new approach to engineering.

Designing systems to manufacture materials that didn’t naturally exist. Controlling processes that had never been controlled. and solving problems that had never been encountered. The uranium slugs that entered the B- reactor were essentially refined metal. The plutonium 239 atoms that emerged had never existed in measurable quantities in Earth’s 4 billionyear history.

The reactor didn’t just process material. It transformed matter at the atomic level, creating new elements through careful manipulation of nuclear reactions. Every modern nuclear technology from medical isotope production to nuclear power plants to radioisotope thermmoelect electric generators for deep space exploration descends directly from engineering principles established at Hanford.

If you’re fascinated by engineering solutions to impossible problems, subscribe to this channel. We explore the technical challenges and ingenious solutions that changed history, focusing on how things actually worked rather than just what happened. Every fact in our videos is verified through historical documentation because your trust in accurate information matters.

Next week, we’re examining another Manhattan Project engineering marvel, the Kutrons at Oakidge, Tennessee. These machines used powerful electromagnets to separate uranium isotopes atom by atom. The magnets required so much copper that the military borrowed 14,700 tons of silver from the US Treasury to wind the magnet coils.

The story involves material shortages, magnetic field stability challenges, and how women graduates from physics and chemistry programs became the primary operators of these impossibly complex machines. Leave a comment. What other Manhattan Project engineering challenges would you like to see covered? The gaseous diffusion plants, the Trinity test site instrumentation, the implosion lens development.

Let me know what technical problems you want explored. The B- reactor’s 12,200 ton graphite cube stands today as a monument to what’s possible when brilliant minds acknowledge uncertainty, build in safety margins, and combine theoretical knowledge with practical engineering skill. Thanks for watching. I’ll see you next week.

News

Beyond the Stage and the Stadium: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Unveil Their Surprising New Joint Venture in Kansas City DT

KANSAS CITY, MO — In a world where celebrity business ventures usually revolve around obscure crypto currencies, overpriced skincare lines,…

Midnight Mercy Dash: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce’s Secret Flight to Dallas to Support Patrick Mahomes After Career-Altering Surgery DT

In the high-stakes world of professional sports and global entertainment, true loyalty is often tested when the stadium lights go…

From Heartbreak to Redemption: Travis Kelce Refuses to Retire on a “Nightmare” Season as He Plots One Last Super Bowl Run Before Rumored Wedding to Taylor Swift DT

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — The atmosphere inside Arrowhead Stadium this past Sunday was unrecognizable. For the first time since 2014,…

Through the Rain and Defeat: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Retreat to New York After Chiefs’ Heartbreaking Loss to Chargers

KANSAS CITY, Mo. – In the high-stakes world of the NFL, not every game ends in celebration. For the Kansas…

From Billion-Dollar Bonuses to Ringless Rumors: The Social Dissects Taylor Swift’s Generosity and the “Red Flags” in Political Marriages DT

In the ever-evolving landscape of pop culture and current affairs, the line between genuine altruism and calculated public relations is…

Tears, Terror, and a New Love: Inside the Raw and Heart-Wrenching Reality of Taylor Swift’s “The End of An Era” Premiere DT

For years, Taylor Swift has been the master of her own narrative, carefully curating the glimpses of her life that…

End of content

No more pages to load