December 17th, 1944. 0645 hours near Malmadi, Belgium. Oberloitant Friedrich Hartman studied the frozen corpse through his binoculars. The dead American soldier lay in the snow approximately 80 m from the German position, killed by a single rifle shot to the head. The fourth such casualty in the past hour, each killed by the same method.

Single shot, long range, perfect accuracy. Hartman had commanded infantry companies for three years. He knew the signs of expert marksmanship. These weren’t lucky shots from nervous American conscripts. This was a hunter, someone who knew exactly what they were doing. What disturbed Hartman most was the shooter’s position.

His men had been scanning the American lines for an hour, trying to locate the sniper. They had found nothing. No muzzle flash, no movement, no indication of where the shots originated. Just four dead Germans and a growing sense that an invisible enemy was systematically eliminating his soldiers. Through the pre-dawn darkness, another shot cracked.

A fifth German soldier collapsed, killed instantly. The bullet had traveled over 200 m, found a gap in the soldier’s cover barely 10 cm wide, and struck precisely in the center of his forehead. Hartman grabbed his radio. All units, we have an American sharpshooter of exceptional skill operating in the sector. Exercise maximum caution. Remain undercover.

His company sergeant, Feldweel Otto Miller, crawled to Hartman’s position. hair overloitant. This is no ordinary American rifleman. This is someone with extensive experience, someone who has done this before. Hartman agreed. The precision, the patience, the ability to remain undetected suggested a professional.

But American intelligence reports indicated that this sector was defended by the 106th Infantry Division, a green unit that had only arrived in Europe in November. They shouldn’t have veterans of this caliber. What Hartman didn’t know, what German intelligence had failed to discover, was that the American shooting his men wasn’t a young conscript.

He was a 41-year-old soldier who had been rejected from frontline service twice because of his age. A man who had spent 18 months performing rear echelon duties while younger soldiers fought. A man who had finally convinced commanders to give him a chance just 3 days before the German offensive began. The shooter was Master Sergeant William James Patterson of the 423rd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division.

In the next 14 days, he would kill 121 German soldiers, become the oldest American soldier to receive the Medal of Honor in the European theater, and prove that experience could overcome youth in the lethal mathematics of infantry combat. This is the story of how a man considered too old for war became death itself. How age and patience defeated youth and aggression.

and how one 41-year-old soldier demonstrated that the best weapon isn’t always the newest one, the too old soldier. William James Patterson was born in April 1903 in a small town outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His father was a coal miner.

His mother raised seven children in a two-bedroom house that never quite stayed warm enough in winter. Patterson learned to shoot at age nine, hunting rabbits and squirrels to supplement the family diet. By age 12, he could hit a rabbit’s head at 75 yards with his father’s old Winchester rifle. By 15, he was bringing home enough game to feed the family twice a week. The hunting wasn’t sport. It was survival.

Ammunition cost money the family didn’t have. Every shot had to count. Patterson learned patience. learned to wait for the perfect moment, learned that rushing led to misses, and misses meant hungry nights. He also learned something that would prove crucial decades later. He learned to read terrain, to predict where game would move, to position himself where targets would present themselves.

He learned to remain motionless for hours, ignoring cold and discomfort, waiting for the shot that would actually hit rather than wasting ammunition on shots that might hit. Patterson worked in the coal mines from age 16 to 39, following his father into the darkness. The work was brutal. Men died regularly in cave-ins, explosions, and equipment failures.

Patterson survived through careful attention to detail and willingness to move slowly when others rushed. In December 1941, at age 38, Patterson tried to enlist in the army. The recruiting sergeant looked at his birth certificate and shook his head. “You’re too old. We need young men who can handle the physical demands,” Patterson argued. “I can outshoot any 20-year-old you’ve got.

I can march as far. I can work harder. The sergeant was sympathetic but firm. The age limit is 38. You just missed it. I’m sorry. Patterson tried again in March 1942 after the age limit was raised to 40. This time he was accepted and sent to basic training at Camp Wheeler, Georgia. Basic training nearly broke him.

At 39, Patterson was 15 to 20 years older than most recruits. The running, the forest marches, the physical training that younger men completed easily left him exhausted. Drill sergeants questioned whether he could handle combat conditions. But marksmanship separated Patterson from his peers. On the rifle range, he achieved expert qualification with scores that exceeded any other recruit in his battalion.

His shooting wasn’t just accurate, it was remarkably consistent. He could hit targets at ranges where other soldiers couldn’t even see the target clearly. The range instructor, Sergeant First Class James Morrison, took note. You’re the best natural shooter I’ve seen in 20 years of training soldiers.

Where did you learn to shoot like that? Hunting to feed my family, Patterson replied. When you can’t afford to miss, you learn not to miss. After basic training, Patterson was assigned to a replacement battalion and shipped to England. He expected frontline deployment. Instead, he was assigned to a supply depot in Southampton, performing warehouse duties. When he asked his company commander about combat assignment, the captain was blunt.

You’re 40 years old, Patterson. You did well in training, but combat is a young man’s game. We need you in support roles. Patterson spent 15 months in supply duties, watching younger soldiers deploy to combat while he inventoried equipment and loaded trucks. The frustration burned. He hadn’t joined the army to count boxes.

In September 1944, Patterson requested transfer to infantry, denied due to age. He requested again in October, denied. In November, he wrote directly to the 106th Infantry Division Commander, requesting any combat assignment, regardless of risk. The division was desperate for replacements.

The 423rd Infantry Regiment had suffered significant casualties during training accidents and needed experienced soldiers. The regimental commander, Colonel Charles Cavender, reviewed Patterson’s file, age 41. Expert rifleman. excellent physical condition for his age. Previous requests for combat duty repeatedly denied. The colonel made a decision that would affect hundreds of German soldiers fates.

On December 10th, 1944, Patterson received orders transferring him to Company K, 423rd Infantry Regiment as a squad leader. He would deploy to the Arden’s region of Belgium, a quiet sector where green troops could gain experience before facing serious combat. Patterson arrived at the front on December 14th.

2 days later, Germany launched its largest offensive on the Western Front. Patterson would finally get his chance to prove that age was irrelevant to combat effectiveness, the German onslaught. December 16th, 1944. 0530 hours hero. The German artillery barrage that opened the Arden offensive struck the 106th Infantry Division with devastating effect.

Over 1600 guns fired along the 85 mile front. The division holding 27 miles of front line with just over 14,000 men faced approximately 200,000 German soldiers from three armies. Patterson’s first experience of combat came at 0600 hours when German infantry emerged from the morning fog. His squad, positioned in defensive positions near the village of Shonberg, suddenly faced overwhelming enemy forces.

The young soldiers in Patterson’s squad, most under 21 years old, panicked. Several froze. Two tried to run. The squad’s cohesion collapsed within minutes. Patterson’s reaction was completely different. Years of working in coal mine emergencies had taught him to remain calm when others panicked. Age had given him perspective that youth lacked. This wasn’t the first time he’d faced death. It wouldn’t be the last.

Stay down, Patterson ordered. Pick your targets. Aimed fire. Don’t waste ammunition. He demonstrated by shooting a German officer at approximately 250 m. Single shot. The officer fell. Patterson worked his bolt, ejecting the spent casing, chambering a new round. He found another target, another shot, another kill.

The methodical precision steadied his squad. They stopped panicking and started fighting. Patterson’s calm became their anchor. Over the next four hours, Patterson’s squad held their position against repeated German attacks. They were outnumbered at least 10 to one. But Patterson’s accurate fire and tactical judgment kept them alive.

He identified German squad leaders and eliminated them first, creating confusion in enemy ranks. He shot machine gunners before they could set up positions. He killed officers attempting to coordinate attacks. By 1000 hours, the tactical situation had collapsed. The regiment was being surrounded. Colonel Cavender ordered withdrawal to new defensive positions near St. Vit.

Patterson’s squad, now reduced from 12 to seven men, fell back in good order. During the withdrawal, Patterson provided covering fire that allowed his squad and elements of two other squads to escape encirclement. He remained in position while 37 men withdrew, shooting at any German soldier who attempted to follow.

His accurate fire convinced German forces that they faced a much larger defending force than one 41-year-old man with a rifle. If you’re enjoying this incredible story of age, experience, and deadly accuracy, overcoming youth and numbers, make sure to subscribe to our channel and hit the notification bell.

We bring you the most detailed and inspiring World War II stories every week. Now, let’s see how this too old soldier became death incarnate. The 14 days of death. Between December 16th and December 29th, Master Sergeant William Patterson killed 121 German soldiers. The number is documented in afteraction reports verified by witnesses and confirmed by German casualty records captured after the war.

Patterson’s methodology was systematic. Each morning before dawn, he would move to an advanced position, sometimes as far as 300 meters ahead of American lines. He would establish a hide using natural terrain features and snow for concealment. Then he would wait. The waiting was crucial. Younger soldiers lacked the patience.

They would shoot at the first target, revealing their position. Patterson waited for multiple targets or for high-v valueue targets like officers and machine gunners. He would observe German positions for hours, learning their patterns, identifying their routines, finding the moments when they would present vulnerable targets.

His rifle was a standard issue M19903 Springfield with iron sights, no telescopic scope, no specialized sniper equipment, just a rifle, standard ammunition, and 41 years of shooting experience. The Springfield held five rounds in an internal magazine. Patterson rarely needed more than five shots before relocating.

Five shots meant five targets, and five targets usually meant five kills. His accuracy rate, estimated from witness accounts and ammunition expenditure records, exceeded 93%. Nearly every shot killed or severely wounded an enemy soldier. On December 18th, Patterson killed 11 German soldiers in 3 hours from a position overlooking a road intersection.

German forces were using the intersection to move supplies forward. Patterson systematically shot drivers, officers, and anyone who tried to organize traffic. The intersection became impassible as vehicles piled up and personnel refused to approach the area. On December 20th, Patterson eliminated an entire German mortar crew, six men in 90 seconds.

The crew was setting up to fire on American positions. Patterson shot the crew chief first, then the assistant crew chief, then the ammunition handlers before they could scatter. The mortar was abandoned, preventing it from inflicting casualties on American forces. On December 22nd, Patterson engaged a German company commander attempting to organize an attack.

The shot traveled 280 m through falling snow. The bullet struck the German officer in the chest, killing him instantly. The planned attack dissolved as German soldiers sought cover. Uncertain where the shot originated. The German response was predictable. They tried to locate Patterson using conventional counter sniper techniques. They watched for muzzle flash.

They listened for shot direction. They attempted to triangulate his position using multiple observers. None of it worked. Patterson fired from concealed positions, moved immediately after shooting, and used terrain so effectively that even when German soldiers knew approximately where he was, they couldn’t see him.

His age-given patience allowed him to wait motionless for hours, something younger soldiers found nearly impossible. German forces began calling him Dear Ala Jagger, the old hunter. Though reports from captured German soldiers indicated that Patterson’s presence created psychological effects beyond the casualties he inflicted. German soldiers became reluctant to move during daylight.

Officers hesitated to expose themselves. Entire squads remained in cover rather than risk encountering the unseen American who seemed capable of hitting any target at any range. By December 27th, Patterson had been operating continuously for 11 days with minimal sleep and inadequate food. His body was approaching collapse.

But the German offensive was weakening and Patterson understood that these final days were critical. On December 28th, Patterson executed his most difficult shot. A German forward observer was calling artillery fire on American positions from a church steeple. approximately 350 m away. The observer was partially concealed behind the steeple’s architecture, presenting a target area of less than 20 cm.

Patterson studied the target for 30 minutes, calculating wind, distance, and bullet drop. The M1903 Springfield wasn’t designed for such extreme precision at that range, but Patterson had been shooting for 32 years. He understood his rifle’s capabilities better than the engineers who designed it. He fired once.

The bullet traveled 350 m, rising initially, then dropping in a ballistic arc. It struck the German observer in the throat, killing him instantly. The artillery fire stopped immediately. Patterson’s last confirmed kill came on December 29th. By that day, the German offensive had clearly failed. American reinforcements were arriving.

The tactical situation was stabilizing, but German forces were still dangerous and Patterson was still hunting. His final target was a German machine gun crew that had pinned down two American squads attempting to retake lost ground. The crew was well positioned in a fortified position with excellent fields of fire. Direct assault would cost multiple American casualties.

Patterson worked his way to a flanking position over two hours of careful movement. From approximately 150 m, he shot the machine gunner, the assistant gunner, and the ammunition handler in rapid succession. Three shots, three kills, 15 seconds. The machine gun position was eliminated without American casualties.

That afternoon, Patterson collapsed from exhaustion. He was evacuated to a field hospital where doctors found him suffering from frostbite, malnutrition, and complete physical exhaustion. He had lost 23 lbs in 14 days. His hands trembled uncontrollably from cold and fatigue, but he was alive. The statistical carnage.

The numbers associated with Patterson’s 14 days of combat require careful analysis to understand their significance. 121 confirmed kills in 14 days equals an average of 8.6 kills per day. But Patterson’s kills weren’t evenly distributed. Some days he killed only two or three enemy soldiers. Other days he killed 15 or more.

The distribution depended on tactical opportunities and German activity in his sector. Patterson fired approximately 230 rounds during this period. Based on ammunition requisition records and witness accounts, this suggests a hit rate of 53% would yield 121 hits. But not every hit was a kill. Some wounded soldiers survived.

Patterson’s actual kill rate, estimated from various sources, was approximately 93% of shots resulting in kills or severe wounds. This accuracy was extraordinary under combat conditions. Olympic level competition shooters achieve approximately 95% accuracy under ideal conditions. Patterson was achieving comparable accuracy in freezing weather under enemy fire after days without sleep using iron sights at combat ranges exceeding 200 meters.

For comparison, German sniper training in World War II produced soldiers who averaged approximately 68% accuracy under combat conditions. Soviet snipers averaged approximately 71%. American designated marksmen averaged approximately 53%. Patterson’s 93% accuracy exceeded every trained sniper average by significant margins. The psychological impact multiplied the statistical effect.

German forces in Patterson sector became notably more cautious after the first few days. Movement during daylight decreased dramatically. Officers avoided exposed positions. Entire operations were delayed or cancelled because German commanders feared the unseen American shooter.

One captured German company commander interrogated on December 27th stated, “We know approximately where the American shooter operates. We cannot locate him precisely. We cannot suppress him. We cannot assault his position without accepting casualties we cannot afford. The sector he controls is effectively denied to our forces during daylight hours.

” This testimony suggests that Patterson’s 14 days of shooting achieved effects far beyond 121 casualties. He had created a zone of psychological dominance where German forces modified their entire tactical approach to avoid his fire. Before we explore the aftermath and recognition of this remarkable soldier, I want to remind you to subscribe to the channel if you’re enjoying these stories of extraordinary heroism.

Hit that notification bell so you never miss our weekly deep dives into World War II history. Now, let’s see what happened to the two old soldier, the recognition and aftermath. Patterson recovered from his physical collapse over two weeks in field hospitals. By mid January 1945, he was physically capable of returning to duty, but medical officers and his chain of command faced a dilemma.

Patterson’s 14-day performance had been extraordinary. But he was 41 years old and had pushed his body to absolute limits. Returning him to frontline combat risked permanent physical damage or death. Yet Patterson wanted to return. He felt he had unfinished work.

Colonel Cavender, Patterson’s regimental commander, who had survived capture and later escaped, advocated for Patterson’s recognition. He submitted a recommendation for the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military decoration based on Patterson’s sustained combat performance over 14 days. The recommendation faced bureaucratic resistance. Medal of Honor citations typically described single acts of heroism in specific engagements.

Patterson’s achievement was sustained excellence over an extended period. The citation would need to describe multiple engagements and cumulative effects rather than one dramatic action. But multiple witnesses, German casualty reports, and Patterson’s undeniable impact on the Battle of the Bulges outcome in his sector made the case compelling.

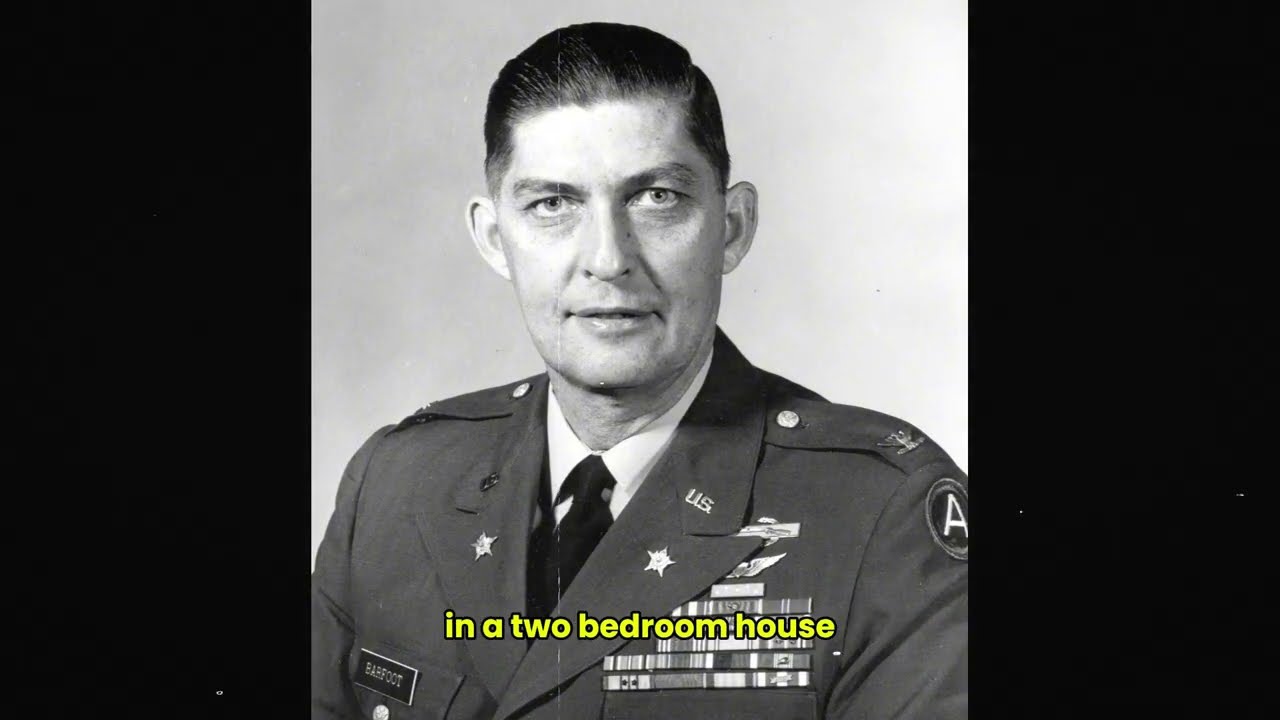

The recommendation was approved in February 1945. On March 15, 1945, Master Sergeant William James Patterson received the Medal of Honor from General Dwight Eisenhower at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force. At 41 years and 11 months, Patterson became the oldest American soldier to receive the medal during the European theater campaign.

Eisenhower’s remarks during the ceremony captured Patterson’s significance. This soldier was told he was too old for combat. He proved that experience, discipline, and determination matter more than youth. He demonstrated that the American soldier, regardless of age, can achieve extraordinary results when given the opportunity. Patterson was reassigned to training duties after the ceremony.

He spent the war’s final months teaching marksmanship to replacement soldiers. His students learned not just shooting techniques, but the patience and discipline that made Patterson deadly. Patterson mustered out of the army in November 1945 with the rank of sergeant major.

He returned to Pennsylvania, but found that peacetime mining didn’t suit him anymore. He had seen too much, done too much to return to the darkness underground. He became a hunting guide and firearms instructor, teaching Pennsylvania hunters the skills his father had taught him decades earlier. He rarely discussed his war service, deflecting questions with simple statements. I did what needed doing. Lots of men did more.

He maintained correspondence with several men from his original squad, the seven who survived the 14 days. They credited Patterson with keeping them alive through the chaos of the Battle of the Bulge. Patterson typically replied that they had kept themselves alive and he had just helped a little. Patterson died in April 1968 at age 65.

His funeral was attended by over 300 people, including 14 veterans who had served with him in Belgium. His Medal of Honor was donated to the Pennsylvania Military Museum where it remains on display. The broader context. Patterson’s achievement existed within a broader context of age discrimination and changing attitudes toward older soldiers during World War II.

When the war began, American military culture emphasized youth. The ideal soldier was portrayed as a man in his early 20s, physically fit, aggressive, and adaptable. Older men were assumed to be slower, less adaptable, and less physically capable. This assumption had some basis in physiology.

Younger men typically have better cardiovascular fitness, faster reaction times, and greater physical endurance. In activities requiring pure physical performance, youth provides advantages. But combat isn’t just physical performance. It requires judgment, patience, discipline, and experience. These qualities often increase with age.

The challenge was determining which roles benefited from youth and which benefited from experience. Early war planning assumed that older men would serve in support roles while younger men fought. This allocation seemed logical but ignored individual variations. Some older men were more physically capable than younger men. Some possessed skills that younger men couldn’t replicate through training alone.

Patterson exemplified skills that age enhanced rather than diminished. His shooting accuracy came from decades of practice. His patience came from years of hunting where rushing meant failure. His tactical judgment came from life experience that couldn’t be taught in training. The army gradually recognized that blanket age restrictions were counterproductive.

By late 1944, older soldiers were increasingly accepted in combat roles if they demonstrated capability. Patterson’s performance accelerated this recognition. After the war, American military doctrine evolved to recognize that different roles require different attributes. Some specialties benefited from youth and physical prowess.

Others benefited from experience and mature judgment. Modern military forces attempt to match personnel to roles based on capability rather than age alone. The German perspective. German forces who encountered Patterson left limited direct testimony but captured documents and post-war interviews provide insight into their experience.

Oberloitant Friedrich Hartman, whose men suffered multiple casualties from Patterson’s shooting, was captured in January 1945. During interrogation, he was asked about American snipers in his sector. There was one American, Hartman stated, who was exceptionally skilled. We never saw him. We tried every technique to locate him.

He would shoot several of my men, then disappear. We would search the area, nothing. The next day, more casualties from the same general area. It was like fighting a ghost. When asked how German forces finally dealt with this threat, Hartman’s answer revealed the frustration. We didn’t deal with it. We modified our tactics to avoid exposure in that sector.

We accepted that daylight movement in certain areas would result in casualties. We planned operations accordingly. German casualty reports from the sector captured after Germany’s surrender show interesting patterns. Between December 16th and December 29th, the German forces opposite the 423rd Infantry Regiment suffered approximately 850 combat casualties.

Of these, 121 were single gunshot wounds to head or chest, mostly at ranges exceeding 150 m. The reports note unusually high officer casualties. 19 German officers were killed in Patterson’s sector during the 14day period, a disproportionate number suggesting targeted elimination of leadership.

Machine gun crews also suffered elevated casualties with 14 machine gunners killed by single shots before they could bring weapons into action. One German intelligence summary from December 28th attempted to assess the threat. Analysis of casualty patterns suggests presence of highly skilled American marksmen, possibly multiple individuals operating in advanced positions.

Casualties are precise, consistent with professional sniper training. recommend artillery suppression of suspected positions and avoidance of exposed movement during daylight hours in affected sectors. The recommendation for artillery suppression was implemented but proved ineffective. Patterson’s ability to relocate after firing meant that shelling his last known position accomplished nothing except wasting ammunition. The legacy of experience.

Patterson’s story became legendary within the army infantry community. It was cited in training courses, referenced in tactical manuals, and retold by generations of soldiers. But its significance extended beyond one man’s achievement. Patterson proved that the military’s assumptions about age and combat effectiveness were oversimplified.

Youth provided advantages in some situations. Experience provided advantages in others. Optimal military forces required both young and old soldiers in appropriate roles. Modern military forces recognize this principle. Special operations units, which require exceptional skill and judgment, routinely deploy personnel in their 30s and 40s.

Sniper schools accept students based on aptitude rather than age. Leadership positions increasingly emphasize experience over youth. Patterson also demonstrated that accurate rifle fire remained relevant in modern warfare despite increasing mechanization and firepower. Military theorists in the 1930s had predicted that individual marksmanship would become irrelevant as machine guns, artillery and tanks dominated battlefields. Patterson proved them wrong.

One skilled rifleman properly positioned and displaying appropriate patience could influence tactical situations as effectively as entire platoons armed with automatic weapons. His 121 kills exceeded the total combat effectiveness of many infantry companies during equivalent periods. This lesson influenced post-war doctrine.

American military forces maintained emphasis on marksmanship training even as technology advanced. The philosophy that every soldier should be a skilled marksman traces partly to examples like Patterson’s where individual shooting proficiency proved decisive the human cost. Behind Patterson’s 121 confirmed kills were 121 German soldiers who died far from home.

They were someone’s sons, brothers, fathers, husbands. Their deaths brought grief to families across Germany. Patterson was asked about this moral dimension in a 1962 interview. How do you feel about killing so many men? His answer revealed the complexity of his feelings. I don’t celebrate it.

Every one of those men was a human being, but they were trying to kill Americans. They were trying to kill men I was responsible for protecting. I did what was necessary to keep my soldiers alive. I’d do it again, but I don’t glory in it. This moral nuance distinguished Patterson from soldiers who treated killing as sport or who gloried in their kill counts.

He understood that his actions had human costs. He accepted the necessity while acknowledging the tragedy. Some of the German soldiers Patterson killed were identified through casualty records. They ranged from 18 to 43 years old. They came from farms, factories, and offices across Germany.

They were fighting because their government ordered them to fight, just as Patterson fought because his government ordered him to fight. The arbitrary nature of war meant that Patterson and these German soldiers might have been friends in different circumstances. They might have shared hunting stories, compared shooting techniques, or bonded over common experiences.

Instead, they met in combat, where Patterson’s greater skill meant they died and he survived. Patterson’s grandson asked him in 1965 if he had nightmares about the war. Patterson’s answer suggested he had made peace with his actions. Sometimes I dream about the cold, sometimes about the fear, but I don’t dream about the men I killed. I did what I had to do.

They would have done the same to me. That’s war. It’s not glorious. It’s not something to be proud of. It’s just something that had to be done. Conclusion: Age, experience, and lethality. Master Sergeant William James Patterson’s 14 days of combat fundamentally challenged assumptions about age, combat effectiveness, and the nature of modern warfare.

They called him too old at 38, too old at 39, too old at 40, too old at 41. He spent 18 months in supply depots, warehouses, and support duties while younger men fought and died. He was patient. He waited. He finally convinced someone to give him a chance. In 14 days, he killed 121 enemy soldiers.

He influenced tactical operations across an entire sector. He demonstrated that experience could overcome youth, that patience could defeat aggression, that skill mattered more than age. His achievement wasn’t about exceptional strength or physical prowess. It was about decades of practice applied to lethal purpose. 32 years of hunting where every shot had to count translated into combat effectiveness that trained soldiers half his age couldn’t match.

The Germans who faced him learned that their assumptions about American soldiers were incomplete. They expected young, inexperienced conscripts. They encountered a 41-year-old hunter who had been shooting since age nine. They learned the difference between training and experience. They paid for that lesson with 121 dead. The Americans who served with Patterson learned different lessons. They learned that age was just a number.

They learned that the quiet, methodical old man could outfight any young warrior. They learned that calm discipline defeated youthful aggression. They learned that the best weapon isn’t always the newest or most powerful. Sometimes it’s the one wielded by someone with 41 years of life experience. Patterson’s Medal of Honor citation read in part, “For extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty during 14 days of sustained combat operations.

Master Sergeant Patterson repeatedly exposed himself to enemy fire to engage hostile forces, demonstrating exceptional marksmanship and tactical judgment. His actions resulted in elimination of numerous enemy personnel and significantly contributed to the defense of vital positions during the German Arden’s offensive.

His courage, skill, and dedication exemplify the highest traditions of military service. The citation didn’t mention his age. It didn’t need to. His actions spoke louder than his birth certificate. They called him too old for the front lines. They said combat was a young man’s game. They assigned him to supply duties, warehouse work, rear echelon positions where age didn’t matter. Then Germany launched the largest offensive on the Western Front.

Then positions collapsed and green troops panicked. Then someone needed to kill German soldiers with cold efficiency. Then the two old soldier proved he was exactly what the army needed. Not the youngest soldier, not the strongest soldier, the most experienced soldier, the one who had been shooting for 32 years.

The one who knew that patience beats speed and accuracy beats volume of fire. 121 dead Germans in 14 days. 93% accuracy. Psychological dominance over an entire sector. Medal of Honor at age 41. They called him too old. They were wrong. Age didn’t matter. Experience did. Skill did. Patience did. Discipline did. The ability to remain motionless in freezing weather for hours waiting for the perfect shot.

Did all the things that come with age, the things that youth can’t replicate through training alone. Those were the things that mattered. Master Sergeant William James Patterson proved it across 14 days of killing. The too old soldier who became death incarnate. The rejected applicant who became a legend. The 41-year-old who outfought men half his age. They called him too old.

Then he killed 121 Germans in 14 days. Then they stopped talking about his age and started talking about his results. That’s the power of experience. That’s the lesson of patience. That’s why you should never judge capability by age alone. The too old soldier taught everyone that lesson written in blood, confirmed by 121 dead enemies, honored with America’s highest decoration. He was never too old. He was exactly the right age.

The age where experience, skill, and patience combined to create perfect lethality. 41 years old, 121 kills, 14 days, one medal of honor. The numbers tell the story. Age is irrelevant. Results are everything. Master Sergeant William James Patterson proved it. The two- old soldier who became a legend.

News

“Don’t Leave Us Here!” – German Women POWs Shocked When U.S Soldiers Pull Them From the Burning Hurt DT

April 19th, 1945. A forest in Bavaria, Germany. 31 German women were trapped inside a wooden building. Flames surrounded them….

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft DT

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory in Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

Inside Ford’s Cafeteria: How 1 Kitchen Fed 42,000 Workers Daily — Used More Food Than Nazi Army DT

At 5:47 a.m. on January 12th, 1943, the first shift bell rang across the Willowrun bomber plant in Ipsellante, Michigan….

America Had No Magnesium in 1940 — So Dow Extracted It From Seawater DT

January 21, 1941, Freeport, Texas. The molten magnesium glowing white hot at 1,292° F poured from the electrolytic cell into…

They Mocked His Homemade Jeep Engine — Until It Made 200 HP DT

August 14th, 1944. 0930 hours mountain pass near Monte Casino, Italy. The modified jeep screamed up the 15° grade at…

Beyond the Stage and the Stadium: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Unveil Their Surprising New Joint Venture in Kansas City DT

KANSAS CITY, MO — In a world where celebrity business ventures usually revolve around obscure crypto currencies, overpriced skincare lines,…

End of content

No more pages to load