German engineers PS trained to believe in their nation’s technological supremacy stood speechless in a Minnesota equipment barn, their hands trembling as they touched an American farmer’s tractor. What Klaus Hoffman discovered on that June morning in 1944 would shatter everything the Nazi regime had taught him and force him to choose between his homeland and the truth.

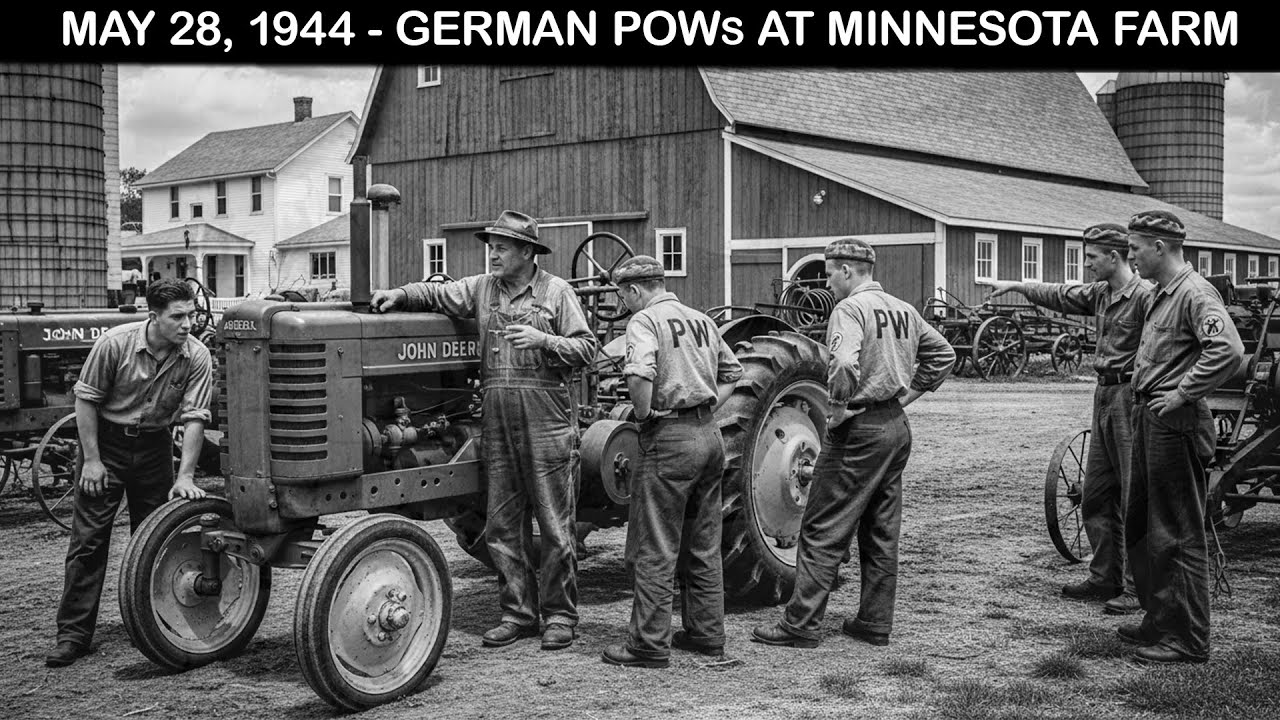

May 28th, 1944, Morehead, Minnesota. The cattle trucks rolled to a stop on the dusty edge of an onion warehouse and 40 German prisoners stepped onto American soil for the first time. Among them was Oberrighter Klaus Hoffman, a 28-year-old former agricultural equipment mechanic from Brandenburgg who had been captured near Tunis 11 months earlier.

He carried nothing but the blue denim workclo with PW stencled on the sleeves that the Americans had issued him at Camp Alona in Iowa. His vermacharked uniform, along with everything he thought he knew about the world, had been left behind in North Africa. Hoffman had spent his youth among the fertile fields of Brandenburgg, where his father ran a small repair shop, servicing the neighborhood’s farm equipment.

Before the war, he had worked alongside his father, maintaining the precious few tractors that local land owners could afford. Most German farms still relied on horses, strong, reliable hannavverians and sturdy Belgian drafts that had served German agriculture for generations. Even in 1939, when Hitler’s Vermacht marched into Poland with its vaunted Panza divisions, the German army itself depended on an estimated 2.

75 million horses for transportation and logistics. By 1941, when Operation Barbarasa launched against the Soviet Union, approximately 750,000 horses accompanied German forces, a number that would only increase as the war progressed and fuel shortages intensified. The irony was not lost on Hoffman.

He had been taught that German engineering represented the pinnacle of human achievement, that the Reich’s technological superiority would ensure victory. Yet he had marched through Tunisia watching supply wagons drawn by requisitioned Polish horses, had seen artillery pieces pulled by animals stolen from French farms. The mechanized blitzkrieg that propaganda minister Ysef Gerbles showcased in news reels represented nearly 20% of the Vermacht’s forces.

The remaining 80%, the vast majority of German soldiers, walked on foot, their supplies hauled by beasts of burden that would not have seemed out of place in Napoleon’s army. June 3rd, 1944, Peterson Farm, Clay County, Minnesota. Six days a week, army trucks collected Hoffman and his fellow prisoners from their makeshift quarters in the converted onion warehouse and transported them to the surrounding farms where Minnesota’s labor shortage had become critical.

The local draft board had stripped the county of 1,500 young men for military service. Without prisoner labor, farmers feared losing their entire vegetable harvest. The federal government, adhering strictly to the Geneva Convention regulations, paid farmers 40 cents per hour for each prisoner’s work. The PS themselves received 10 cents per hour in Camp Script, redeemable only at the camp canteen.

Henry Peterson, a prosperous vegetable farmer, had contracted for 20 prisoners to work his fields. He was a third generation American of Norwegian descent, a man whose grandfather had broken the prairie soil with oxen. Now Peterson operated one of the most modern farms in Clay County, and it was here that Klaus Hoffman’s education truly began.

On his first morning at the Petersonen farm, Hoffman stood in the equipment barn, while dawn light filtered through the gaps in the weathered boards. Before him sat a John Deere Model B tractor, its distinctive green paint gleaming even in the dim light. The machine was a 1941 model, one of the long frame versions produced just before America’s full entry into the war.

It featured the styled bodywork designed by industrial designer Henry Drifus with a gracefully curved radiator grill and an enclosed engine housing that suggested both power and modernity. But it was not the aesthetics that struck Hoffman speechless. It was the casual abundance of it all. This was not the only tractor on the Petersonen farm.

Through the barn’s open doors, he could see two more machines, a larger John Deere model A and an International Harvester Farm M3 tractors on a single farm operated by one family. Hoffman’s hands trembled as he approached the model B. The guard, a middle-aged corporal from Iowa with a German surname, noticed his interest.

“You know tractors?” the guard asked in accented German, his family’s mother tongue not yet forgotten. “I was a mechanic,” Hoffman replied softly. “Before the war,” he ran his hand along the tractor’s smooth fender. “The machine was equipped with an electric starter and lights, luxuries that even wealthy German landowners rarely possessed.

Back home, the few tractors Hoffman had serviced were often makeshift affairs, cobbled together from whatever parts could be obtained, running on airsat’s fuel when petroleum was unavailable. During the war years, Germany’s agricultural mechanization had actually decreased as tractors were requisitioned for military use or cannibalized for parts.

June 15th, 1944, Camp Alona, Iowa. Two weeks into his farm labor assignment, Hoffman was temporarily returned to the main camp at Alona for a medical checkup. The base camp, built in 1943 at a cost of 1,028 million and 287 acres of Iowa farmland, housed up to 3,000 prisoners at any given time and served as the administrative center for 34 branch camps scattered across Iowa, Minnesota, South Dakota, and North Dakota.

Since its opening in April 1944, more than 10,000 German PSWs had passed through Algon’s gates, most of them like Hoffman, veterans of Irvin Raml’s Africa Corps, who had surrendered to Allied forces in Tunisia. In the camp’s recreation hall that evening, Hoffman sat with a group of fellow mechanics and engineers.

Among them was Friedrich Vber, a former tank commander who had served with the 21st Panza Division. Weber was from the Rur Valley, Germany’s industrial heartland, and he possessed an engineer’s mind for systems and production. Three tractors, Weber repeated incredulously when Hoffman described the Peterson farm. On one farm, Klouse, that’s impossible.

Even the model farms in the Reich propaganda films didn’t have that many. I’ve seen it with my own eyes, Hoffman insisted. And not just tractors. They have a combine harvester, self-propelled. They have a mechanical corn picker. They have equipment I’ve never even seen before. Another prisoner, a farmer named Hans Dietrich from East Prussia, shook his head slowly.

We were told America was weak, that they were soft, that their economy was collapsing. That’s what the party said. That’s what all the newspapers said. The newspapers lied, Hoffman said simply. The room fell silent. Even in captivity, even thousands of miles from the Reich, such statements felt dangerous. But the evidence was becoming impossible to ignore.

Every prisoner who worked on American farms returned with similar stories. The abundance wasn’t propaganda. It was reality. July 4th, 1944, Independence Day celebration, Peterson Farm. Henry Peterson, in violation of camp regulations, but guided by a farmer’s practical sense of humanity, invited his prisoners to join the farm’s Independence Day celebration, the guards, mostly older men deemed unfit for combat duty, looked the other way as Petersonen distributed cold beer and hamburgers to the Germans.

It was here, sitting on hay bales in the summer twilight, that Hoffman experienced a conversation that would haunt him for the rest of his life. Peterson’s son, James, had just returned from basic training at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri. At 19, he would soon be deployed to Europe, possibly to fight the same army that Hoffman had served.

Yet here they sat, sharing a meal and struggling through a conversation in broken German and halting English. “Your farm,” Hoffman ventured, searching for words. “How many hectares?” “About 240 acres,” James replied. That’s about 97 hectares. I think Hoffman did the mathematics in his head. The average German farm was perhaps 20 hectares.

This single American family operated a farm five times that size, and they did it with just three men and their machinery. In Germany, Hoffman said slowly, “A farm this size would need maybe 20 workers. 20 families?” James shrugged. “Before the war, Dad had maybe four hired hands during harvest. Now it’s just him and me when I’m home, plus you fellas. The tractors do the rest.

That night, lying on his cot in the onion warehouse, Hoffman couldn’t sleep. He kept thinking about the mathematics of it all. If American agriculture was this mechanized, this efficient, then American industry must be operating on a scale that German propaganda had never hinted at.

And if American industry was that powerful, then the war he didn’t want to finish the thought. August 17th, 1944. Branch Camp Morehead, Minnesota. The summer of 1944 was one of the busiest in Minnesota agricultural history. More than 2,400 German PS working out of seven southern Minnesota branch camps saved an estimated 65% of a record-breaking pea crop.

According to a press release from Camp Alona’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur T. Lobdell. The prisoners worked from dawn to dusk, 6 days a week, and were paid their 80 cents per day in campscript. Some sent money home to their families. Others saved it, hoping to have something when they returned to a Germany they increasingly feared would be destroyed.

Hoffman had become an invaluable worker at the Petersonen farm, not just for his strong back, but for his mechanical knowledge. When the Model B developed engine problems in mid August, Peterson asked Hoffman to diagnose the issue. With the guard’s permission, Hoffman spent 3 hours in the equipment barn, systematically troubleshooting the tractor’s fuel system.

The problem turned out to be simple, a clogged fuel filter. But the process of fixing it revealed something more profound to Hoffman. The tractor’s design was elegant, logical, accessible. Every component was labeled. parts were standardized, interchangeable. This wasn’t just a machine. It was a system designed for efficiency and reliability.

It was built to be maintained by farmers, not engineers. Back in Germany, the few tractors Hoffman had worked on were often finicky, overengineered affairs that required specialist knowledge. Replacement parts were scarce, often requiring improvisation or custom fabrication. The contrast was stark.

American equipment was designed for abundance, for a nation that assumed resources would be available. German equipment was designed for scarcity, for a nation that had been preparing for war and rationing since the early 1930s. When Hoffman got the Model B running again, Peterson clapped him on the shoulder with genuine appreciation.

And you know, the farmer said through the interpreter, after the war, if you wanted to stay in America, I could sponsor you. Could use a mechanic like you. The offer was casual offh hand, but it struck Hoffman like a physical blow. Stay in America. The thought had never occurred to him. He was German. Germany was his home.

But what was Germany now? What would it be when the war ended? September 15th, 1944. Camp Alona, Iowa. On this date, the Alona P system reached its peak population of 5,152 captives spread across the main camp and its extensive network of branches. The prisoners had become an integral part of the regional economy. They worked in caneries, nurseries, lumber mills, and farms throughout the upper Midwest.

They cut timber in northern Minnesota’s forests, detassled hybrid corn for decal and pioneer seed companies, and processed vegetables in dozens of rural communities. For many prisoners, the work was monotonous, but not difficult. The food was adequate, far better than what German civilians were receiving under wartime rationing.

The guards were generally reasonable. Some prisoners even formed friendships with local families. But for men like Klaus Hoffman, every day brought a new revelation that chipped away at the ideological foundations of their youth. By September 1944, the war news was becoming impossible to ignore. Allied forces had liberated Paris on August 25th.

Soviet armies were advancing through Poland. Germany itself was under constant aerial bombardment. Letters from home when they arrived at all told of destruction, food shortages, and despair. Yet here in Iowa, America’s heartland, life continued with an abundance that seemed almost obscene. Farmers complained about labor shortages, but still managed to produce record harvests.

Small town businesses thrived. Cars and trucks filled the roads despite gasoline rationing. The disconnect between Germany’s collapsing reality and America’s barely interrupted prosperity was becoming too obvious to deny. October 28th, 1944. Harvest season, Klay County, Minnesota. The fall harvest was the busiest time of year, and every available prisoner was deployed to the fields.

Hoffman found himself working alongside American farm equipment that represented the cutting edge of agricultural technology. The self-propelled combine harvester that Peterson used could do the work of 30 men with sythes and threshing machines. It could harvest, thresh, and clean wheat in a single pass across the field, depositing clean grain directly into trucks that ran parallel to the machine.

Back in Brandenburgg, harvest time meant weeks of backbreaking labor. Men, women, and children worked from dawn to dusk, cutting grain by hand or with horsedrawn reapers, bundling sheav, shocking them in the fields to dry, then hauling them to stationary threshing machines powered by belt-driven engines when fuel was available.

When it wasn’t, horses walked in circles, providing the power through mechanical gearing. The contrast was stark and undeniable. American agriculture wasn’t just more mechanized. It was operating on a fundamentally different scale of technological and economic development. One evening, as they were loading the last truck of wheat, Hoffman asked Peterson a question that had been troubling him for weeks.

“This equipment?” he said through the interpreter. “Is your farm unusual? Are most American farms like this?” Peterson laughed. “Hell no. I’m doing pretty well, I admit. But I’ve got friends in Iowa and Nebraska with farms twice this size with more equipment than me. And out in California, they’ve got corporate farms that make this place looked like a garden plot.

Hoffman felt something crack inside his chest. Not just Germany would lose this war. The Germany he had known, the Germany of Nazi propaganda, of promises of Laben’s realm and racial destiny, had already lost. It had never stood a chance. December 21st, 1944. Christmas at Camp Alona. The winter of 1944 to45 marked a turning point for many prisoners.

The Battle of the Bulge, Hitler’s last desperate gamble in the West, had begun on December 16th. Initial reports suggested German success, but the prisoners who followed the news closely, men like Hoffman and Weber, understood what the offensive really represented. the death throws of a dying army. At Camp Alona, a German prisoner named Edoard Kaib, a commercial artist and radio operator captured near Nice, France had been working on an extraordinary project while being treated for an ulcer in the camp hospital that fall. The homesick Kibbe

began creating a nativity scene using scavenged materials and some of his prisoner pay. With five other prisoners, he shaped more than 60 half-life-sized figures on concrete wire frames, finishing them in plaster and painting them with meticulous care. The nativity first made news in the Kosut County advance on December 21st, 1944.

Camp Commander Lieutenant Colonel Lobdell was impressed by the artistry and suggested Kib expand the project. For many prisoners, including Hoffman, the nativity represented something profound, an assertion of humanity in the midst of war, a reminder that German culture was more than military conquest and Nazi ideology.

On Christmas Eve, Hoffman stood before the completed nativity with tears streaming down his face. He thought of his parents in Brandenburgg, wondered if they were still alive, if their house still stood. He thought of the mechanized abundance he had witnessed on American farms and the horsedrawn poverty of German agriculture.

He thought of the tractors, those magnificent, efficient machines that represented everything his country had failed to become. February 10th, 1945, returned to Petersonen Farm. The winter months meant less field work, but Petersonen had asked specifically for Hoffman to return to the farm for maintenance work on his equipment fleet.

Over the winter, Hoffman completely overhauled all three of Petersonen’s tractors, serviced the combine harvester, and repaired various smaller implements. He worked in the heated equipment barn, often alone with the guard reading magazines near the stove. It was during these quiet winter days, that Hoffman began to truly understand what had gone wrong.

Germany had pursued technological excellence in weapons of war, producing tanks like the Tiger and Panther that were marvels of engineering but nightmares of production, requiring skilled labor and rare materials that Germany didn’t possess in sufficient quantities. Meanwhile, America had focused on mass production and standardization, creating vast numbers of adequate vehicles and weapons supported by an industrial base that could simply outproduce any competitor.

The same logic applied to agriculture. Germany had dreamed of conquering vast territories in the east to feed its people, using slave labor and stolen resources. America had simply mechanized its farms, allowing smaller numbers of workers to feed larger populations with everinccreasing efficiency. One approach required conquest and oppression.

The other required innovation and capital investment. By February 1945, Hoffman had made his decision. When the war ended, and it would end soon, he was certain, he would take Henry Petersonen up on his offer. He would stay in America, not because he hated Germany, but because the Germany he loved, the Germany of poets and composers, of craftsmen and farmers, had been destroyed not by Allied bombs, but by the Nazi regime that had claimed to protect it. May 8th, 1945.

Veday, Camp Alona, Iowa. The war in Europe ended on May 8th, 1945 with Germany’s unconditional surrender. At Camp Alona, the news was met with a complex mixture of emotions. Relief that the killing had stopped, grief for a defeated homeland, anxiety about an uncertain future. Many prisoners openly wept. Lieutenant Colonel Lobell assembled the prisoners and addressed them through an interpreter.

“The war is over,” he said simply. You will be held here until arrangements can be made for your repatriation. You have worked hard and behaved honorably. Ply thank you for that. But Hoffman knew that repatriation would not be quick. Germany was destroyed. The infrastructure was shattered. Millions of refugees were on the move. Food was scarce.

And the discoveries being made in the liberated concentration camps, news of which was filtering into the camp through newspapers and radio broadcasts, had revealed horrors that made every German, even those who had never supported the Nazi regime, feel a collective shame. July 1945, a letter home.

Hoffman managed to send a letter to his parents through the International Red Cross. It was brief, as all prisoner correspondence was limited and censored. But he tried to convey something of what he had learned. Dear mother and father, I am well and healthy. The Americans treat us fairly. I have been working on a farm in Minnesota, and I have learned much about modern agriculture.

The farmers here have machines that can do the work of 20 men. They have tractors and harvesters such as I never imagined existed. When I return, and I do not know when that will be, I hope that we can rebuild. Not the Germany of the past few years, but the Germany of craftsmanship and learning that we once knew.

I have seen that there are other ways to live, other ways to organize society, and perhaps we can learn from this. The farmer I work for, Mr. Peterson, says that American farmers would welcome German agricultural expertise after the war when things are normalized. Perhaps there will be opportunities for exchange, for learning, for building something better than what we lost.

I pray that you are safe and that our house still stands. I think of you every day, your son, Klaus. The letter, like many such letters, would take months to arrive. When it did, it would find Klaus Hoffman’s parents living in the ruins of what had been Brandenburgg, struggling to survive in the Soviet occupation zone. They would never see their son again.

Klouse would make the difficult decision to remain in America, eventually becoming a US citizen, opening his own farm equipment repair business in Iowa and marrying the daughter of a local implement dealer. September 15th, 1945, peak population revisited. One year after Camp Alona reached its peak population, the system held approximately the same number of prisoners, but the mood had changed entirely. Germany had surrendered.

The war in the Pacific would end on August 15th with Japan’s capitulation. Now the prisoners were simply waiting, existing in a strange limbo between their defeated past and an uncertain future. Hoffman continued working at the Petersonen farm through the fall harvest of 1945. By now he could operate all the farm equipment with expert precision.

He could diagnose and repair mechanical problems faster than the local implement dealer. He had become in effect Peterson’s farm manager, supervising other prisoners and coordinating the harvest operations. In October, Peterson formally submitted the paperwork to sponsor Hoffman for immigration. The process would take time.

Bureaucracy moved slowly, even in victory, but the wheels were in motion. January 1946. Repatriation and choice. The mass repatriation of German PS from the United States began in earnest in early 1946. By February, Camp Alona would be virtually empty, its prisoners returned to a Germany divided into occupation zones, its cities reduced to rubble, its people traumatized and guiltstricken.

But Klaus Hoffman was not among those who boarded the transport ships. His immigration paperwork, expedited by Peterson’s connections and Hoffman’s demonstrated value as a skilled worker, had been approved. On January 15th, 1946, he signed papers formally requesting to remain in the United States as a legal immigrant.

The decision was agonizing. His parents were still in Germany in the Soviet zone, and communication was increasingly difficult. His homeland, for all its sins and failures, was still his homeland. But he had seen too much, learned too much. He understood now that the Germany of Nazi propaganda had been a lie, built on theft and sustained by violence.

The thousand-year Reich had lasted 12 years and left Europe in ruins. America was not perfect. He had learned that, too. He saw the segregation that limited where black Americans could live and work. He saw the Native American communities marginalized on reservations. He saw poverty alongside abundance. But he also saw a system that for all its flaws was built on a foundation of productivity rather than conquest, of innovation rather than oppression.

And he had seen those tractors, those magnificent, efficient, beautifully designed machines that represented a different way of thinking about the world. Not machines of war, but machines of life. Not built to conquer, but to cultivate.

News

The Kingdom at a Crossroads: Travis Kelce’s Emotional Exit Sparks Retirement Fears After Mahomes Injury Disaster DT

The atmosphere inside the Kansas City Chiefs’ locker room on the evening of December 14th wasn’t just quiet; it was…

Love Against All Odds: How Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Are Prioritizing Their Relationship After a Record-Breaking and Exhausting Year DT

In the whirlwind world of global superstardom and professional athletics, few stories have captivated the public imagination quite like the…

Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Swap the Spotlight for the Shop: Inside Their Surprising New Joint Business Venture in Kansas City DT

In the world of celebrity power couples, we often expect to see them on red carpets, at high-end restaurants, or…

The Fall of a Star: How Jerry Jeudy’s “Insane” Struggles and Alleged Lack of Effort are Jeopardizing Shedeur Sanders’ Future in Cleveland DT

The city of Cleveland is no stranger to football heartbreak, but the current drama unfolding at the Browns’ facility feels…

A Season of High Stakes and Healing: The Kelce Brothers Unite for a Holiday Spectacular Amidst Chiefs’ Heartbreak and Taylor Swift’s “Unfiltered” New Chapter DT

In the high-octane world of the NFL, the line between triumph and tragedy is razor-thin, a reality the Kansas City…

The Showgirl’s Secrets: Is Taylor Swift’s “Perfect” Romance with Travis Kelce a Shield for Unresolved Heartbreak? DT

In the glittering world of pop culture, few stories have captivated the public imagination quite like the romance between Taylor…

End of content

No more pages to load