At 0612 a.m. on December 8th, 1941, William Mure stood in the center of Curtis Wright’s main production floor in Buffalo, New York. The radio had been on all night. Pearl Harbor was burning 3,000 mi away. He looked at the assembly line stretching into darkness. 37 P40 Warhawk engines sat incomplete. Outside, the city was still asleep.

Inside the machines had already started. The telegram arrived at 0900. Priority 1: war department. The message was three lines long. Double production. Triple shifts. No delays permitted. Mure read it twice. Then he walked to the planning office and pulled every blueprint off the wall. Before we continue, if stories like this one matter to you, stories about the people who built the machines that won the war, consider subscribing.

These aren’t just tales of metal and fire. They’re about the invisible hands that shaped history. In December 1941, the United States was not ready for war. The Army Air Forces had fewer than 2,000 combat ready aircraft. Japan had 4,000. Germany had 5,000 more. American factories were producing civilian cars, refrigerators, radios.

The assembly lines ran 8 hours a day, 5 days a week. Workers went home at 5. War was an abstraction, something happening in newspapers on distant continents. The industrial base existed. The factories stood. The machines waited, but they were calibrated for peace, configured for profit, optimized for a world that no longer existed. The P40 Warhawk was America’s frontline fighter, fast, maneuverable, armed with 650 caliber machine guns.

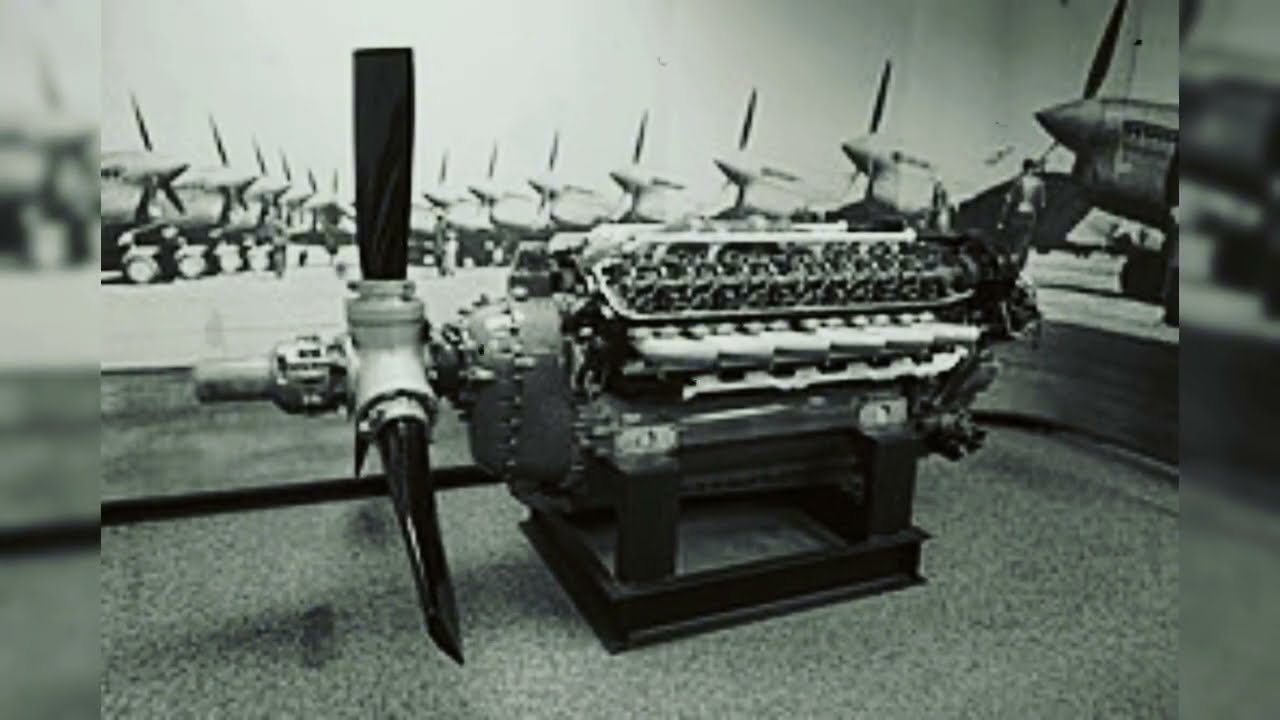

In North Africa, it fought German Messers. In China, it flew with the Flying Tigers. In the Pacific, it was all that stood between Japanese zeros and American bases. The aircraft had proven itself, but the aircraft was not the limitation. The engine was the Allison V1710. 12 cylinders arranged in a V configuration, liquid cooled, 1,00 horsepower at takeoff.

Maximum RPM 3,000. weight 1,395 lbs. Every P40, every P39, every P63 depended on this single engine design. And in December 1941, Curtis Wright was producing 70 engines per month. 70 engines per month meant 840 engines per year. The War Department’s initial estimate called for 24,000 aircraft by the end of 1942. Each aircraft needed an engine.

Some needed two. The mathematics were brutal, clear, undeniable. 70 engines would not win the war. 70 engines would not even delay the loss. The bottleneck was not knowledge. Engineers understood metallurgy. They knew tolerances. They had mastered the thermodynamics of internal combustion. The bottleneck was time.

Each engine required precision machining on components that could not be rushed. Crankshafts had to be balanced within grams. Cylinder bores had to be honed to within 10,000 of an inch. Timing mechanisms had to be calibrated by hand. And all of this took time. Time to machine, time to assemble, time to test, time the war would not allow.

The problem was not design. The Allison V1710 was a proven engine. The problem was scale. Each engine required 3,000 individual parts. Bearings from Ohio, pistons from Michigan, cylinder heads from Pennsylvania, magnetos from Illinois. Every component had to arrive on time, fit perfectly, and function under combat stress at 20,000 ft.

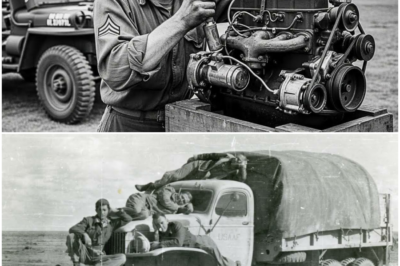

One missing bolt could ground an aircraft. One faulty gasket could kill a pilot. And now the War Department wanted 2,000 engines per month. William Mure was 52 years old. He had worked for Curtis Wright since 1927. He understood tolerances, clearances, metallurgy. He knew how long it took to machine a crankshaft, mill a cylinder head, hand fit a rocker arm.

He knew the mathematics were impossible. 2,000 engines per month meant 66 engines per day. That meant one engine every 22 minutes. Every single minute of every single day. No breaks, no failures, no room for error. He called a meeting at midnight. The engineers arrived in coats over pajamas. Mure stood at the front of the room and wrote a single number on the blackboard.

142,000. That was the total, the number of engines the War Department projected they would need by 1945. Engines for P40s in North Africa. Engines for P39s in the Pacific. Engines for P63s not yet designed. Engines for aircraft that existed only as sketches. Someone in the back asked if it was possible. Mure didn’t answer.

He just kept writing numbers, hours, shifts, workers, materials. By the time he finished, the blackboard was covered in calculations that all led to the same conclusion. They would need to hire 180,000 workers. They would need to run the factories 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for 4 years. They would need to machine 36 million individual parts without a single day of rest.

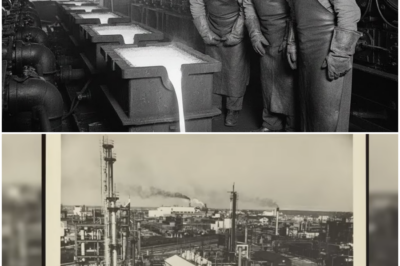

The room stayed silent for a long time. Then Muer turned around and said one sentence, “We start tomorrow.” By January 1942, Curtis Wright had begun the largest industrial mobilization in American history. The Buffalo plant expanded. New buildings rose in weeks. Concrete poured at night. Steel frameswelded by dawn.

Within 3 months, the factory floor covered 42 acres under a single roof. Assembly lines stretched half a mile. Overhead cranes moved cylinder blocks the size of automobiles. The noise was constant, mechanical, inhuman. But buildings were not enough. Machines were not enough. What Curtis Wright needed most were people. The first recruitment wave targeted men, skilled machinists, tool and die makers, engineers.

Within weeks, every qualified man in Buffalo had been hired. Then the recruitment expanded to Rochester, to Syracuse, to Cleveland. Recruiters set up tables in bus stations, train depots, factory towns across the Midwest. The promise was simple. steady work, union wages, a chance to fight the war from home.

By March, they had hired 20,000 workers. It was not enough. The arithmetic was relentless. 20,000 workers could produce perhaps 300 engines per month, maybe 400 if they worked longer hours. But the War Department wanted 2,000. and 2000 meant finding bodies, training hands, installing equipment, expanding floor space at a pace that defied every norm of industrial planning.

So Curtis Wright did something unprecedented, something that violated social convention, labor tradition, and the expectations of every factory in America. They opened the production floor to women. In 1942, women were not machinists. They were not welders. They were not engineers. They were secretaries, nurses, teachers.

Society had decided their role, and that role did not include cutting steel, operating lathes, or handling machinery that could sever a hand in less than a second. The factory floor was male territory, dangerous, physical, unsuitable for women. But the war did not care about society’s rules. The war needed engines.

And engines needed hands, trained hands, steady hands, hands willing to work 10-hour shifts in conditions that broke men who had done it for decades. The first women arrived in April 1942. They wore dresses and gloves. They carried lunchboxes and uncertainty. They walked through the factory gates past men who stared, men who muttered, men who placed bets on how long these women would last before they quit.

The women kept walking through the noise, through the skepticism, through the heat that made the air shimmer and the machinery that roared like something alive. The foreman met them at the entrance to the training floor. His name was Raymond Kowalsski. He had worked in factories for 32 years. He did not smile. He handed each woman a set of coveralls and told them to change.

The coveralls were not optional. Neither was the work. Neither was precision. The training lasted 2 weeks, 14 days to learn what men had spent years mastering. How to read a blueprint. How to measure with a micrometer. How to operate a drill press without losing a finger. A lathe without losing a hand.

A grinder without losing an eye. The instructors were blunt. Mistakes killed pilots. Precision saved lives. There was no space for mediocrity, no tolerance for error, no safety net for incompetence. Either you learned or you left. Some left. Most stayed. They learned to read tolerances measured in thousandth of an inch.

They learned to recognize the sound of a drill bit cutting too fast, a grinding wheel losing balance, a hydraulic press losing pressure. They learned that metal had texture, resistance, memory, that every material responded differently to force. that steel cut clean, but aluminum tore if you pushed too hard. That brass was soft, but copper was softer.

That temperature changed everything. By the end of 2 weeks, they were no longer women in coveralls. They were machinists. By June 1942, 12,000 women were working on the Curtis Wright production line. They machined crankshafts. They assembled fuel pumps. They riveted engine cowlings. They worked 10-hour shifts.

They worked through air raid drills. They worked with hands blistered and backs aching. And the engines kept coming. One engine every 22 minutes, then one every 18, then one every 15. The production line was not a place of comfort. It was a place of mathematics. Every motion was timed. Every task was measured. Industrial engineers stood with stopwatches and clipboards recording how long it took to install a piston, torque a bolt, test a fuel line.

They broke each task into increments, calculated optimal positioning, eliminated wasted movement. The goal was not humanity. The goal was efficiency. Workers stood in the same position for hours. Some installed cam shafts. Some calibrated magnetos. Some inspected valve springs with gauges that measured fractions of millimeters.

The assembly line never stopped. Overhead conveyors carried engine blocks from station to station. If someone fell behind, the entire sequence collapsed. Engines piled up half finishedish. Inspectors rejected parts. Schedules disintegrated. Supervisors shouted. Production numbers plummeted. So no one fell behind.

They learned to ignore pain. Ignore fatigue, ignore theburning in their shoulders, the cramping in their hands, the numbness in their feet. They learned to work through everything except death. And sometimes even that did not stop the line. In July 1942, a machinist named Thomas Brennan collapsed at his station. Heart attack.

54 years old, 30 years in factories. He fell forward onto the drill press he had been operating. The drill was still spinning. By the time someone reached him, it was too late. They covered his body with a tarp, shut down his machine, moved his station to the side of the floor. The line kept running. His replacement arrived within an hour.

There was no memorial service, no moment of silence. The work did not allow for mourning. The war did not allow for sentiment. Thomas Brennan’s name appeared in the Buffalo Evening News. Three lines, page 14. Factory worker survived by a wife and two daughters. Services pending. That was all. The engines kept coming.

If you’re still with us, thank you. Stories like these take time to research, time to write, time to bring back from the edge of forgetting. If you want to see more, hit that subscribe button. There are more stories, more engines, more people who refused to fail. Inside the Curtis Wright factory, the rhythm was relentless.

Morning shift arrived at 0600, afternoon shift at,400, night shift at 2,200. Three shifts, seven days a week, no holidays, no exceptions. Workers clocked in, walked to their stations, and became part of the machine. The line moved. They moved with it. The work was not heroic. It was repetitive, exhausting, and invisible.

A woman named Dorothy Klene spent eight months installing oil pumps. the same part, the same motion 8,000 times. She never saw a P40 fly. She never met a pilot. She only knew that if she installed the pump wrong, someone would die. So, she never installed it wrong. The pressure was constant. Inspectors walked the line every hour.

They carried calipers, micrometers, feeler gauges. They checked tolerances down to thousandth of an inch. If a part was off by a fraction of a millimeter, it was rejected. If a worker made three mistakes, they were removed. There was no second chance. There were 10,000 people waiting outside for their job. Quality control was not negotiable.

Every completed engine underwent a 50-hour test run before shipment. The process was methodical, exhaustive, unforgiving. Each engine was mounted on a steel test stand in a dedicated building separated from the main production floor. The test cells were designed to contain catastrophic failures, reinforced concrete walls, blast proof doors, ventilation systems that could evacuate smoke in seconds.

because engines did fail and when they failed at full throttle they failed violently. The test began with a cold start. Technicians primed the fuel system, checked oil levels, verified electrical connections. Then they engaged the starter. The engine coughed, sputtered, caught. The sound built slowly, a rumble that grew into a roar.

12 cylinders firing in sequence. Exhaust flames licking the manifolds. For the first 10 hours, the engine ran at idle, 800 RPM. Technicians monitored oil pressure, coolant temperature, fuel consumption. They listened for irregular firing, watched for oil leaks, checked for vibrations that indicated imbalanced components.

Any anomaly triggered an immediate shutdown and disassembly. If the engine survived idle, the test progressed 1,500 RPM for 5 hours, 2,000 RPM for 10 hours, 25,500 RPM for 15 hours. Each stage pushed the engine closer to combat conditions. Temperatures climbed, metal expanded, gaskets compressed, bearings wore, weaknesses revealed themselves.

The final test was full throttle, 3,000 RPM, maximum power. The noise was overwhelming. The test cell vibrated. Technicians wore ear protection and stood behind protective barriers. They watched gauges. Oil pressure 70 PSI. Coolant temperature 180° F. Manifold pressure 42 in of mercury. Every reading had to stay within specification.

Any deviation meant failure. Engines that failed the test were torn apart. Every component examined. Every surface inspected. Engineers documented the failure mode, identified the cause, traced it back through the supply chain to the worker, the machine, the batch of raw material that produced the defect. Then they fixed the process, retrained the worker, re-calibrated the machine, rejected the material supplier, and they started over.

One defective engine could destroy the reputation of the entire factory. And reputation meant contracts. Contracts meant survival. So quality was not a goal. It was an obsession, a religion. The only thing that mattered more than speed was reliability. Because speed without reliability killed pilots and dead pilots lost wars. By August 1942, Curtis Wright was producing 1,000 engines per month.

It was not enough. The war was expanding. North Africa, the Pacific, Italy. Every theater needed aircraft. Every aircraft needed an engine. And every engine took70 hours to assemble. So Curtis Wright did what seemed impossible. They sped up. Engineers redesigned the assembly process. Tasks were divided into smaller increments.

Workers specialized in single operations. One person installed pistons. Another torqued cylinder heads. Another tested electrical systems. The assembly line became a mechanical ballet. Every motion choreographed. Every second accounted for. Waste was eliminated. Efficiency became religion.

By October, production reached 1,500 engines per month. By December 2000, the factory never stopped. When machines broke down, they were repaired during shift changes. When tools wore out, they were replaced overnight. When raw materials ran short, trains arrived at 03 a.m. with steel from Pittsburgh, aluminum from Tennessee, copper from Montana.

The logistics were staggering. Every day Curtis Wright consumed 200 tons of metal. Every week they shipped 400 engines. Every month the numbers climbed. But numbers did not tell the whole story. Behind every engine was a person. Behind every person was a life interrupted by war. Margaret Howell was 19 years old when she started at Curtis Wright.

She had been studying to become a teacher. She wanted to work with children, help them read, show them the world through books. The war ended that plan. The war ended a lot of plans. She learned to weld instead. 10 hours a day, she fused aluminum engine mounts with an oxy acetylene torch that burned at 3,000° F. The work required absolute precision.

The aluminum had to be heated to exactly the right temperature. Too cold and the weld would not bond. Too hot and the metal would warp, rendering the entire component useless. She wore a welding mask, heavy leather gloves, a canvas apron, but protection was limited. The heat was unbearable. Summer temperatures inside the welding bay exceeded 100°.

The ventilation systems ran constantly, but could not keep pace with the heat generated by 200 welding stations operating simultaneously. The light was blinding. Even through the tinted mask, the ark flash left spots in her vision. After a 10-hour shift, she could barely see. She would walk home in the dark, blinking, her eyes burning, her face red from heat exposure.

The sparks left scars on her arms, small craters where molten metal had landed on exposed skin. She learned to ignore the pain. Everyone did. Burns were so common, the factory kept a medical station stocked with nothing but burn ointment and bandages. But the pay was $40 a week. More than her father made working as a clerk.

More than any woman in her town had ever earned. Money that meant something. Money that bought war bonds. Money that kept her family’s house. Money that proved women could do more than society believed possible. She sent $20 home every week. Her mother cried when the first envelope arrived, not because of the money, because of what the money represented.

Her daughter was working in a factory, doing a man’s job, coming home with scars and exhaustion. It was not the future they had planned. But Margaret kept welding. She kept the other $20 for rent, food, and war bonds. She bought one bond every month, $25 each. She kept them in a drawer, never cashed them.

Even after the war, even when money was tight, she never cashed them. They were not currency. They were proof. Proof that she had been part of something larger than herself. Her brother was a pilot somewhere in the Pacific. She did not know where. Letters took months to arrive. When they did, entire paragraphs were blacked out by sensors.

Location redacted, mission redacted. Even the weather was classified. All she knew was that he flew a P40 Curtis P40 Warhawk powered by an Allison V1710 engine. The same engine that started its life on an assembly line in Buffalo. Maybe even the same line where she welded engine mounts. She never told anyone that. She just kept welding.

Every weld perfect, every joint flawless. Because somewhere in the Pacific, her brother was flying. And if her weld failed, if her work was careless, if she made a mistake, it might be his engine that failed, his aircraft that fell, his life that ended. So she never made a mistake. Not once in 3 years, not once in 8,247 welds. Not once.

By 1943, Curtis Wright had become a city within a city, an industrial empire that spanned six states and employed 180,000 workers. Buffalo remained the heart, the largest facility, the proving ground for new techniques. But the war demanded more than one factory could produce. Additional plants opened in Columbus, Ohio, Cincinnati, Ohio, Lachland, Ohio, Louisville, Kentucky.

Each facility specialized in specific components. Columbus produced crankshafts. Cincinnati machined cylinder blocks. Lachland manufactured connecting rods. Louisville assembled fuel systems. The components were then shipped by rail to Buffalo for final assembly and testing. The logistics were staggering.

Every day, dozens of freight trains arrived carrying raw materialsand partially completed components. Steel from Pittsburgh, aluminum from Alcoa’s plants in Tennessee, copper from Montana, rubber from synthetic plants in Texas. Each material had to arrive on time in the correct quantity, meeting exact specifications. A single delay could cascade through the entire production system.

If crankshafts from Columbus were late, the Buffalo assembly line stopped. If cylinder blocks from Cincinnati failed inspection, production targets collapsed. If connecting rods from Lachland did not meet tolerance specifications, entire batches were rejected and the factory fell behind schedule. Supply chain managers worked 20our days coordinating shipments, tracking inventory, negotiating with suppliers.

They had direct lines to the war production board, authority to commandeer rail cars, power to requisition materials from other contractors. The industrial hierarchy was clear. Aircraft engines came first. Everything else waited. The factories operated as a synchronized system, a mechanical organism with 180,000 moving parts.

Each worker was a component. Each shift a cycle, each day a measurement of efficiency. The system was not designed for comfort or humanity. It was designed for output, maximum output, sustainable output, output that could be maintained for years without collapse. And it worked. By mid 1943, Curtis Wright was producing 2500 engines per month.

By September 3000, the numbers kept climbing. Not because workers worked faster, they could not work faster. They were already operating at the limit of human endurance. The numbers climbed because the system became more efficient. Tasks were divided into smaller increments. Equipment was improved. Processes were refined.

Industrial engineers documented every motion, calculated every delay, eliminated every instance of wasted effort. They timed how long it took a worker to walk from one station to another. They measured the angle at which tools were positioned. They analyzed the impact of lighting on productivity. Every variable was studied.

Every improvement was implemented. The result was not heroism. It was optimization. The assembly line became a machine that consumed human labor and produced engines with mathematical precision. The workers were not soldiers. They did not carry rifles. They did not storm beaches. But they fought the war in a different way, with precision, with endurance, with the knowledge that every engine they built carried a pilot’s life.

There were no parades for them, no medals, no monuments, just wages, exhaustion, and the silent certainty that their work mattered. The strain was physical. Repetitive motion injuries became epidemic, carpal tunnel, tendinitis, chronic back pain. Workers wore braces, swallowed aspirin, and kept going. Some collapsed on the line.

Others worked through fevers, through fractures, through grief. Foreman looked the other way. Production could not stop. The strain was also emotional. Every worker knew what the engines were for. They listened to the radio during breaks. They heard the casualty reports. They read the names in newspapers. And they wondered if the engine they built yesterday was flying today.

if it was still flying, if the pilot made it home. Most of them never knew. In February 1943, a P40 Warhawk with serial number 437824 took off from Henderson Field on Guadal Canal. The engine was an Allison V1710 serial number 2847-B built in Buffalo on October 14th, 1942. Assembled by a team of eight workers over the course of 14 hours.

Tested for 50 hours on test stand number seven. Passed all inspections. Crated. Shipped to San Diego. loaded onto the cargo vessel USS Arcturus. Transported across 8,000 miles of Pacific Ocean, unloaded at a Spitus Santo, flown to Henderson Field, installed in a Warhawk that had already flown 63 combat missions. The installation took 6 hours.

Three mechanics worked through the night. They mounted the engine to the airframe, connected fuel lines, routed coolant hoses, attached electrical systems, calibrated the propeller governor, double-cheed every connection, torqued every bolt to specification. By dawn, the aircraft was ready. The pilot’s name was Lieutenant Daniel Morse, 22 years old, from a farming town in Iowa with a population of 847.

He had enlisted 3 days after Pearl Harbor, completed flight training in Texas, earned his wings in April 1942, arrived in the South Pacific in July. He had been flying combat missions for 7 months. In that time he had flown 112 sorties. He had engaged enemy aircraft 37 times, shot down three confirmed kills, two probables.

He had been hit by ground fire twice, lost hydraulics once, crash landed on a coral runway, and walked away with a bruised shoulder and fractured pride. He had watched friends die, watched aircraft explode in midair, watched parachutes fail to open, watched the ocean swallow burning metal and screaming men.

He had stopped writing letters home because he no longer knewwhat to say. How do you tell your mother you might not survive the week? How do you tell your father that every morning might be your last? So he stopped writing. He flew. He fought. He survived. That was enough. On February 18th, 1943, his mission was reconnaissance. Standard patrol.

Fly north along the coast. Look for enemy shipping. Avoid contact if possible. Engage only if necessary. Return by nightfall. He took off at 0615. The morning was clear, visibility unlimited, wind from the southeast at 8 knots, temperature 76°. Perfect flying weather. The engine ran smoothly. Oil pressure 68 psi.

Coolant temperature 175°, RPM 2400. All readings normal. The Warhawk climbed to 8,000 ft. leveled off. Morris checked his instruments. Fuel sufficient for four hours. Ammunition full. Radio functional. He flew north. The ocean stretched endlessly below. Blue, empty, indifferent. 50 mi north of Guadal Canal, the engine changed pitch, a subtle shift, almost imperceptible.

But Morse had been flying long enough to know every sound the Allison V1710 made. This sound was wrong. Oil pressure began to drop. Slowly at first, then faster. 65 psi. 60 55. The gauge needle fell like a stone. Temperature spiked. 180° 190 200. The cockpit filled with the smell of burning oil. Morse reduced throttle, tried to stabilize.

The engine coughed, sputtered. The propeller began to windmill. He could feel the resistance through the controls. Something internal had failed. A bearing, a seal, a pump. He tried to restart. Engaged the primer, hit the starter. Nothing. The engine was dead. 12 cylinders, 1,000 horsepower, reduced to silent, useless metal.

The Warhawk began to descend. Without power, it was just a glider, a heavy, poorly designed glider. He had maybe 5 minutes before impact. He radioed Henderson, transmitted his position, reported engine failure, requested emergency assistance. The response was calm, professional. They would send search aircraft.

He should prepare for water landing. Water landing was a euphemism. It meant crash. It meant hoping the aircraft stayed intact long enough to escape. It meant hoping the ocean was calm enough to survive. It meant hoping rescue arrived before sharks did. Morse tightened his straps, released the canopy, prepared for impact. The ocean rose up smooth, deceptively gentle.

At 120 mph, water becomes concrete. The Warhawk hit hard. The nose dug in. The tail flipped up. The impact snapped Morse forward against his restraints. His head hit the gunsite. Blood filled his vision. The cockpit filled with water. He released the straps, pushed away from the sinking aircraft, surfaced, gasped.

The Warhawk slipped beneath the waves slowly, almost gracefully. The tail stayed visible for a few seconds. Then it too disappeared. Morse floated alone 50 miles from land. He inflated his life vest, checked for injuries, broken nose, possible concussion, otherwise intact. Rescue crews never found him. Search aircraft flew the grid for 3 days.

They found nothing. No wreckage, no debris, no body. The ocean had swallowed everything. His name was added to a list. Missing in action, presumed dead. His parents received a telegram. Standard format. The Secretary of War regrets to inform you. Their son had given his life in service to his country.

They never knew the engine failed. They never knew about the oil pump. They never knew about the microscopic fracture in a casting that should have been caught during inspection. Years later, investigators would analyze similar failures. They discovered a defect in a batch of oil pumps manufactured between October 10th and October 20th, 1942.

A fracture in the casting, invisible to standard inspection, fatal under sustained stress. The defect originated at a foundry in Canton, Ohio. A mold that cracked due to thermal stress. a temperature variance of 15°. A quality inspector who missed the flaw because he had worked a 16-hour shift and his eyes no longer focused properly and his judgment had been compromised by exhaustion.

300 engines contained that defect. Most of them flew without incident. 12 did not. Lieutenant Daniel Morse was one of 12. Years later, investigators would analyze similar failures. They discovered a defect in a batch of oil pumps manufactured between October 10th and October 20th, 1942. A microscopic fracture in the casting, invisible to inspection, fatal under stress.

300 engines contained that defect. Most of them flew without incident. 12 did not. Dorothy Klene never knew. She kept installing oil pumps until the war ended. She kept the same rhythm, the same precision. She never made a mistake. But the mistake had already been made somewhere upstream in a casting foundry in Ohio.

A mold that cracked, a temperature that dropped, a quality inspector who missed the flaw because he had worked a 16-hour shift and his eyes no longer focused. War is not won by heroes alone. It is won by supply chains, by logistics, by 10,000invisible decisions made correctly. And it is lost by a single invisible decision made wrong.

By 1944, Curtis Wright was producing 3,000 engines per month. The factories operated at maximum capacity. The workers moved like machines. The machines moved like inevitabilities. The line never stopped. The war never stopped. But the cost was becoming visible. Workers aged faster. Faces thinned, eyes hollowed. The young women, who had arrived in 1942 with hope and uncertainty, now moved with mechanical efficiency and silent exhaustion.

They had spent three years doing the same task, the same motion thousands of times until the motion became reflex until the reflex became identity. They were not teachers. They were not wives. They were not dreamers. They were machinists, welders, inspectors. They were the people who built engines. And they would carry that identity long after the war ended.

If this story moved you, if you see your own family in these faces, in these hands that built the machines that built the victory, then please subscribe. There are more stories, more names, more moments that history almost forgot. In April 1945, the war in Europe ended. In August, Japan surrendered.

The factories kept running. Orders still came. engines still shipped, but everyone knew the rhythm was ending. On September 2nd, 1945, the official surrender was signed. That night, the Curtis Wright factories in Buffalo went silent for the first time in 4 years. The assembly line stopped. The machines cooled. Workers stood at their stations and waited for someone to tell them what to do next.

No one knew. By October, half the workforce had been laid off. By December, most of the factories had closed. The war was over. The engines were no longer needed. The people who had built them were no longer needed either. Margaret Howell returned to school. She never finished. She got married instead, had children, worked part-time at a department store.

She never welded again. But sometimes when an aircraft passed overhead, she stopped and listened. And she remembered the heat, the sparks, the scars on her arms. Dorothy Klene moved to California. She worked in a factory that made refrigerators. The rhythm was the same. The precision was the same, but the stakes were not.

She retired in 1972, died in 1989. No one at her funeral knew she had built engines. She had never told them. William Mure stayed at Curtis Wright until 1958. He watched the company decline, watched the factories close, watched the assembly lines rust. He retired with a gold watch and a pension. He lived to be 83. He never spoke about the war.

The numbers are recorded. 142,000 engines built by 180,000 workers over 4 years. 426 million hours of labor. 3 billion individual parts. Every one of them mattered. Every one of them was forgotten. The Curtis Wright factories in Buffalo were demolished in 1974. The land was sold. Apartments were built, shopping centers, parking lots.

Nothing remains. No plaque, no memorial. No acknowledgement that the largest industrial mobilization in human history happened there. But the engines remain. Some still fly. restored P40s at air shows, museums, private collections. The roar of an Allison V1710 at full throttle is unmistakable. 12 cylinders, liquid cooled, 1,000 horsepower.

The same sound pilots heard in 1943. The same sound that carried them into combat. The same sound that sometimes brought them home. And when those engines start, when that sound echoes across an airfield, it carries more than noise. It carries the memory of 180,000 hands. Hands that welded, machined, assembled, inspected. Hands that blistered, bled, and refused to fail.

Those hands built the war, but history forgot their names. This is what remains. Not monuments, not speeches, just the sound of an engine starting, just the memory of work, just the knowledge that once in a factory in Buffalo, 180,000 people refused to let the world fall into darkness. They built engines and the engines flew and the world survived. That is the story.

Quiet, invisible. True. The assembly line is gone now. The workers are gone, but the engines still run. And when they do, listen closely. You can hear the war. You can hear the exhaustion. You can hear the refusal to quit. You can hear the sound of 180,000 people who never gave up. That sound is all that remains.

News

“Don’t Leave Us Here!” – German Women POWs Shocked When U.S Soldiers Pull Them From the Burning Hurt DT

April 19th, 1945. A forest in Bavaria, Germany. 31 German women were trapped inside a wooden building. Flames surrounded them….

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft DT

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory in Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

Inside Ford’s Cafeteria: How 1 Kitchen Fed 42,000 Workers Daily — Used More Food Than Nazi Army DT

At 5:47 a.m. on January 12th, 1943, the first shift bell rang across the Willowrun bomber plant in Ipsellante, Michigan….

America Had No Magnesium in 1940 — So Dow Extracted It From Seawater DT

January 21, 1941, Freeport, Texas. The molten magnesium glowing white hot at 1,292° F poured from the electrolytic cell into…

They Mocked His Homemade Jeep Engine — Until It Made 200 HP DT

August 14th, 1944. 0930 hours mountain pass near Monte Casino, Italy. The modified jeep screamed up the 15° grade at…

Beyond the Stage and the Stadium: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Unveil Their Surprising New Joint Venture in Kansas City DT

KANSAS CITY, MO — In a world where celebrity business ventures usually revolve around obscure crypto currencies, overpriced skincare lines,…

End of content

No more pages to load