June 6th, 1943, at 7:14 a.m. the test bay inside Pratt and Whitney’s East Hartford plant shook so hard that workers thought another engine had exploded. The R2800 double Wasp prototype on the stand was screaming at combat power. The gauges vibrating the whole concrete floor humming. A supervisor yelled to shut it down.

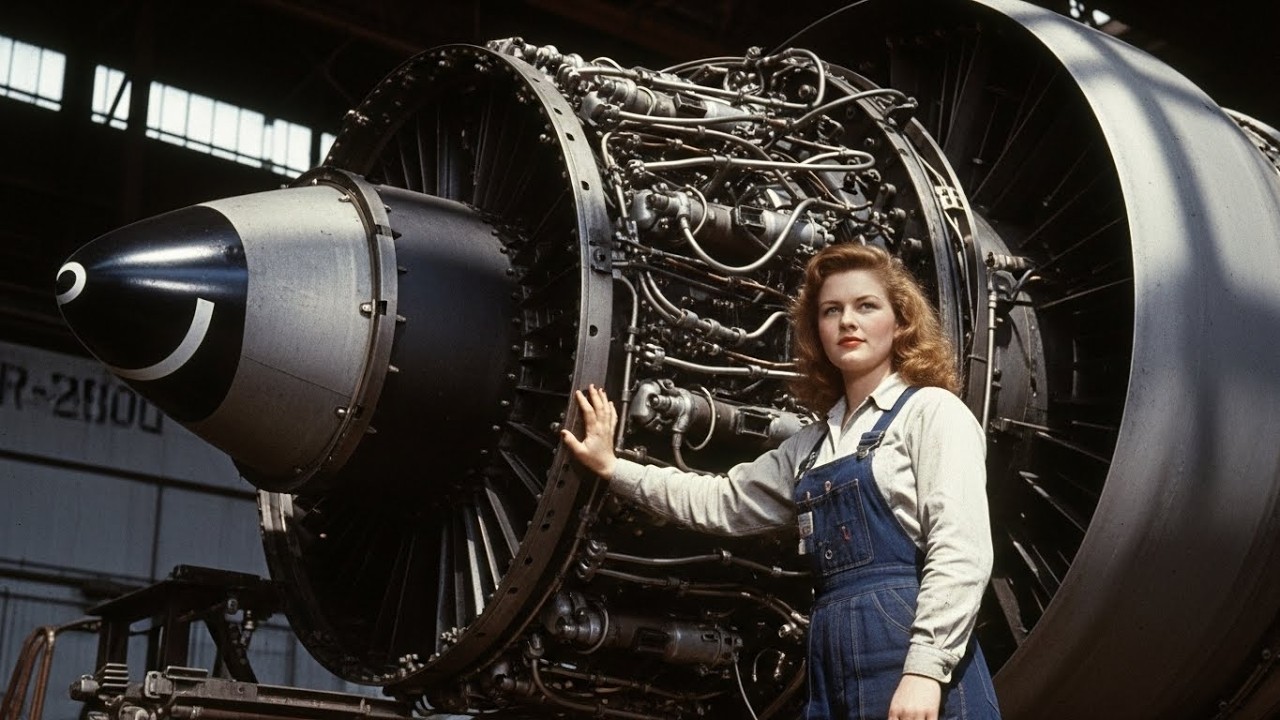

Another shouted that detonation was spiking again. Someone swore that the bearings were seizing. Men in white shirts and loosened ties rushed toward the viewing window, expecting to scrap yet another unit after weeks of impossible failures. And then, in that blur of noise and heat and panic, a young riveter, 22 hair tied up under a stained cap on her 11th straight hour, saw something no engineer in that room had caught. A shimmer. Not on the gauges, on the engine casing itself.

A tremor out of rhythm with the others, the kind that doesn’t come from combustion, but from the tiniest shift inside a rotating assembly. She stepped closer. Someone told her to move back. She didn’t. The vibration wasn’t random. It pulsed once every revolution, which meant a tolerance error smaller than a human hair deep inside the connecting rod assembly.

A mistake you couldn’t see unless you lived with metal every day. At 7:17 a.m., the engine finally choked and died coughing smoke through the test stand vents. The engineers marked it for scrap. The plant manager said the design was cursed. The double wasp, America’s miracle engine, the one meant to push fighters to 30,000 ft and outrun the Luftwaffa’s best, kept failing at the exact point where pilots would need it most.

And yet she stayed by the stand staring at the metal while everyone else walked off to their target blueprints. According to the test logs I read, this was the moment that changed everything. When a machine built for thousands of horsepower was saved by someone whose job description never included saving anything.

I keep wondering why she paused there, as if she sensed the war bending around a flaw nobody else noticed. Because that microscopic error, that missing sliver of a thousandth of an inch, stood between American pilots and the cold, thin air where engines died and men died with them. If this engine couldn’t survive full military power, then P47s would keep falling, bombers would keep burning, and the skies over Europe would keep belonging to someone else.

But the truth is more unnerving. The engine didn’t fail because it was weak. It failed because it wasn’t finished. Not yet. Not until someone outside the design room saw what the design room couldn’t. She placed her hand on the warm casing, felt the offbeat tremor, and in that strange quiet second after the noise stopped, she knew what to look for.

The problem was microscopic. The consequences were continental. And the fix would force America to rethink how wars are actually won. Because while the world argued about horsepower, horsepower, horsepower, she was about to prove that survival lived in the space between decimals.

And that discovery would travel from this noisy factory floor straight into a future where pilots pulled war emergency power at 30,000 ft and lived. But we are not there yet. First, we need to understand why the skies over Europe were killing engines faster than America could build them. At first glance, it looked like an engineering problem. But by late 1943, the real issue was thousands of miles east above France and Germany, where engines weren’t failing in test bays.

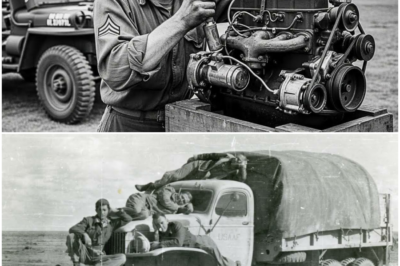

They were failing in combat. And when a power plant quit at 26,000 ft, nothing existed between a pilot and a blacked out sky except a prayer and a parachute he might never get to use. According to the eighth Air Force maintenance summaries from that summer, engine failures were the second most common reason a P47 didn’t return.

Not enemy fire, not weather, engines that simply quit breathing, and the pilots knew it. They felt it in the climb when the needle crept toward war emergency power. They felt it again in the thin air above 27,000 ft where the Luftvafa held all the advantages that mattered. The German fighters didn’t need to be faster.

They just had to be waiting. Imagine a bomber stream of B17 flying fortresses stretching 50 mi long, moving at something barely above cruising speed, unable to outclimb or outrun anything. They needed escorts. Escorts that could stay with them from takeoff in England all the way to the deepest industrial zones of Germany.

But in 1943, before the long range P-51 Mustang arrived in numbers, America depended on the P-47 Thunderbolt, a brute of a machine, thick-skinned, heavily armed, capable of surviving punishment no other Allied fighter could endure. But it had a weakness that no armor plate could fix. Fuel burn skyrocketed at high power. Every minute spent clawing upward on overheating engines cost a minute of escort time.

And when the Luftvafa hit the bomber stream, usually around noon, when the sun burned off the cloud cover, the Thunderbolts had already burned through too much fuel just to get into position. The Germans understood the timing so well that their attack windows appeared predictable on paper. 10:45 a.m. near the Dutch coast. 11:22 a.m. over the Rer. 12:05 p.m. near Castle.

a rhythm of ambushes built around the Thunderbolts inability to climb quickly or stay at power for long without its engine cooking itself from the inside out. When I look at the reports, what strikes me is how the pilots describe the sound.

A faint knock, a sudden drop in manifold pressure, a cough at the worst possible second, and then sometimes silence. What makes this more complicated is that the Luftvafa was not yet broken. In mid 43, their ACE pilots averaged hundreds of sorties. Their Faula Wolf 190 fighters performed best in the medium to high altitude band exactly where the American bombers had to pass.

And they believed correctly that if the Americans couldn’t keep their escorts alive long enough to push through the defenses, then the entire concept of daylight strategic bombing would collapse. This is the part that keeps circling back in my mind. America didn’t need more firepower. It had that already. It didn’t need more factories. They were roaring.

It needed reliability more than that predictability. An engine that performed the same way at sea level and at 30,000 ft. An engine that tolerated bad fuel ice crystal shrapnel and the savage habit of pilots pushing throttles past red lines when survival depended on it. But the R2800 wasn’t there yet. On paper, the Double Wasp could produce over 2,400 horsepower.

With water injection, it could surge even higher toward that astonishing 3,600 figure that engineers whispered about, but rarely used outside emergencies. But the surge meant nothing if the engine shook itself to pieces under the slightest misalignment.

A war emergency rating becomes irrelevant if the detonation threshold is unpredictable. Look at the casualty curves. In early 43, some bomber missions lost one bomber out of every four. By autumn, even with Thunderbolts flying escort losses remained catastrophic. And deep strike missions into places like Schwinfort and Rigensburg names now synonymous with sacrifice showed the tragic equation.

If escorts couldn’t stay, bombers died. If engines couldn’t climb, escorts couldn’t stay. If reliability faltered, strategy collapsed. It really was that simple. And this is where the story shifts. Because while generals debated doctrine in conference rooms, the real pivot point of the air war was happening at the level nobody paid attention to.

The rivet, the micrometer, the fraction of a thousandth of an inch on a part spinning thousands of times per minute. That young woman in East Hartford had no reason to know any of this. She had never seen a Luftwafa fighter. banking in for the kill. She had never watched contrails twist like threads across a frozen sky. But the correction she was about to make would give American pilots a weapon they’d never truly had before.

Trust. Trust that when they shoved the throttle forward at 28,000 ft, the engine would answer with power instead of failure. Trust that the double wasp could sustain full climb without burning itself alive. trust that the fight ahead would be determined by skill, not mechanical roulette.

But to understand how her hands, raw, tired, steady, made that possible, we need to understand the world she stepped into every day. The noise, the heat, the repetition, and the relentless pressure to build engines faster than a continent could shoot them down. Because the next link in this chain is not a battlefield.

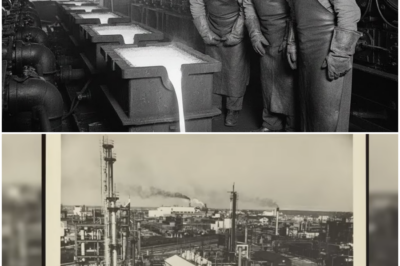

It is a factory floor crowded with women who had never planned to build war machines. yet somehow built the most important ones America ever produced. They called it the Arsenal of democracy long before anyone understood what that actually meant. By the summer of 1943, the roar inside Pratt and Whitney’s factories had become a second atmosphere, a constant metallic thunder that swallowed conversation thought even fear.

Women stepped into that noise the way pilots stepped into cockpits, knowing what waited ahead, but never fully prepared for the weight of it. The factory opened at 6:30 a.m. Yet, most workers arrived earlier, partly to find a spot on the crowded benches in the breakroom, partly because buses were unreliable, mostly because the war didn’t care about time cards.

Once the whistles blew, the line surged forward, and the day began in a blast of heat and pressure that didn’t end until well past sunset. The women who built the R2800 weren’t machinists. Not at first. Some had been seamstresses, some waitresses, some high school seniors who had never touched industrial metal before walking into these cavernous buildings with their towering ventilators and worring overhead cranes.

And yet day after day they learned the language of steel. The pitch of a drill that bit too deep, the faint buzz that meant a bearing seat wasn’t true. The strange silence when apart fit perfectly. The first time which almost never happened.

The factory air tasted of cutting oil, aluminum dust, and hot varnish from the magneto windings. The floors rumbled from test stands running day and night. Workbenches were stained with the fingerprints of hundreds of shifts, each one pushing the limits of exhaustion just a little further. If you read the training manuals today, everything looks clean and procedural. Torque specifications, measurement diagrams, thread allowances, but those pages never capture what the workers themselves described the physical strain of tightening hundreds of bolts in a row until wrists throbbed the vibration that crept up their arms. After hours of

operating pneumatic riveting guns, the ringing in their ears that followed them home and into sleep. They carried that sound like an invisible badge, a reminder that the war was not somewhere else. It was here humming inside their bones.

By mid-43, nearly half of Pratt and Whitney’s assembly line workers were women. 6 million women across America were now building ships, wiring aircraft, forging tank armor, inspecting ammunition. They stepped into roles that had never been offered to them before and were told to learn fast because the enemy wasn’t waiting. And they did learn fast faster than anyone expected.

One foreman wrote that new female recruits achieved precision in 3 weeks that had taken male apprentices 3 months before the war. Another noted that rejection rates on critical parts dropped sharply once the night shift switched to an all-women crew. Still, none of this came easily.

The heat in the crankcase forging bays often pushed the temperature above 90°. Many women wore bandanas because stray strands of hair near a drill press could be fatal. Gloves wore out every few days. Fingernails tore. shoulders achd from lifting jigs heavier than children, but they kept showing up. 10-hour days became 12. Six day weeks became seven when orders surged.

They lined up for coffee at midnight, wiping metal dust from their cheeks as if it were ordinary powder. They laughed sometimes, cried sometimes, argued with supervisors, and then returned to the exacting rhythm of wartime production. And yet the part that stays with me is something quieter. A detail buried in one worker’s diary from 1943.

She wrote that whenever an engine left the assembly floor for testing, she felt a strange tug in her chest, as if a piece of her own effort were being sent into danger. That sense of responsibility, the idea that her accuracy could protect someone far away shaped the culture of the entire factory. These women worked under an unspoken truth. Every fraction of a thousandth of an inch mattered because every inch of sky a pilot climbed depended on them.

In this world of grinding repetition of heat and noise, and the constant rattle of tools patterns eventually emerged. Good parts had a certain feel, a certain weight. Flawed parts felt different barely subtly. And that intuitive knowledge built from sweat rather than textbooks created a kind of second sight. Which explains why when the double wasp on the test stand began vibrating out of sequence, it wasn’t an engineer who sensed the real problem. It was someone whose hands had touched hundreds of these engines, someone who could feel a

defect before she could name it. She didn’t know it yet, but that tiny instinctive recognition would soon collide with the needs of a world at war because the next step wasn’t observation. It was intervention. And once she stepped forward, once she pointed to the flaw no one else could see, the entire course of engine developme

nt, and the air war itself would begin to shift. At 7:19 a.m. on a Wednesday in late August 1943, the test crew wheeled another R2800 onto stand 5. A steel cage bolted into the concrete to contain the violence of a full power run. The engineers expected trouble. Every prototype in this batch had shown the same maddening symptoms.

A deep unsettling shutter at high manifold pressure, a spike in exhaust temperature, and then sometimes without warning, a catastrophic drop in oil pressure that forced an emergency shutdown. The official explanations circled endlessly. detonation, fuel inconsistency, turbocharger air flow instability, anything except the possibility that the problem lived inside the engine’s own heart.

The crew primed the oiling system, fuel lines clicked into place. A mechanic yelled all clear. At 7:21 a.m., the starter winded and the 18 cylinder radial coughed itself awake, shaking the test cage as the props blurred into a silver disc. The sound hammered through the factory walls. People paused midtask, listening for the telltale vibration that had haunted the last six tests.

Within minutes, as the throttle eased past climb power, the vibration returned slight at first, then growing in amplitude until even workers in the adjoining bay could feel it buzzing through the concrete. Most observers saw chaos. She saw a pattern. One pulse out of rhythm for every complete rotation of the crank.

Not random, not combustion, mechanical, repeatable, and dangerously precise. She leaned closer to the safety railing, ignoring a supervisor’s order to stay back. The frequency wasn’t drifting. It held steady. And that steadiness meant only one thing. The misalignment wasn’t thermal. It wasn’t fuel. It was geometry.

Something off by the width of a pencil line shaved into dust. A tolerance error. Too small for a ruler, but too large for an engine spinning thousands of revolutions per minute. When the shutdown signal finally flashed, the noise died in a series of choking backfires. Hot metal ticked as it cooled. Engineers descended on the engine with clipboards and calipers. They checked magnetos plugs, fuel injectors.

They opened cowling panels and measured everything except the one area she kept staring at the connecting rod assembly deep inside the crankcase where a misaligned bearing could transform a perfect design into a self-destructing machine. She wasn’t supposed to speak. Line workers rarely did in front of the engineering staff, but she stepped forward anyway.

There is a moment in the test log, one brief line that confirms it. A suggestion from a riveter led to inspection of crankpin tolerances. No name, no attribution, just a note. According to her co-workers later accounts, she pointed at the engine mount and said the vibration matched a misaligned rod.

The engineers dismissed it at first. That assembly had already passed inspection. The tolerances were within spec. Everything on paper was correct. And yet the engine kept failing. Something in her certainty forced them to check again. They pulled the crankcase apart, piece by stubborn piece, until they reached the rod bearings. One of the machinists held up a part and squinted.

The light caught the surface at an odd angle, a shadow where no shadow should have been. A ridge so faint that even a micrometer hesitated. When they measured it, the truth snapped into focus. a deviation of 3/10,000 of an inch. Enough to throw the entire rotating assembly out of harmony at high power. Enough to create the death shutter pilots had reported before crashing.

Enough to kill any man who trusted the engine with his life. The engineers stood stunned. The misalignment didn’t show up under static inspection because most test protocols never pushed parts to the extremes pilots used in combat. The flaw only revealed itself under the brutal stress of full war emergency power settings pilots reached daily.

Somehow she had recognized the signature of that flaw through sound and feel alone. Her supervisor asked her how she noticed it. She shrugged. She said the vibration felt wrong. Not louder, not sharper, just wrong. The kind of intuition that only forms after months of touching metal until you understand its moods. This discovery forced a complete halt in production. Parts already boxed for shipment were recalled.

Machining protocols were rewritten overnight. Precision tightened. Quality control checks multiplied. The double wasp suddenly had a new enemy. The microscopic imperfections of American speed itself. And the solution began with workstations like hers, where hands came away blackened with aluminum dust and ears rang long after the shift ended. What fascinates me most when reading these records is the pivot point they represent.

A war machine worth more than a small town was undone by a sliver of misalignment and saved by someone whose job title did not include saving anything. But the consequences of her insight would travel far beyond this test bay. Because once the tolerances changed, once the design team realized what the engine really needed to survive high altitude combat, the double wasp was no longer just powerful.

It became dependable. And dependable engines were exactly what the air war over Europe was about to demand. The pilots still climbing into their P47s did not know that the difference between life and death had just been measured in 10,000 of an inch.

They only knew they needed more power, more reliability, and more time in the sky before fuel or failure forced them to turn back. And now, for the first time, the engine might finally be ready to give them all three. By the time the corrected R2800’s left East Hartford and Middletown in the winter of 1943, the war they were built for had already shifted into something far more brutal than the engineers had imagined.

Across the Atlantic, over the gray skies of occupied Europe, the Eighth Air Force was bleeding aircraft at a rate no democracy could tolerate for long. The Schweinfort raids had torn holes in America’s faith that courage alone could break the industrial spine of the Reich. Pilots climbed into their thunderbolts every morning, knowing the arithmetic was against them.

A fighter with an unreliable engine was not a weapon. It was a sentence. The new engines arrived just as that sentence was coming due. The first squadrons to receive the recalibrated double wasps were cautious at first. Maintenance chiefs inspected every crate. Test pilots took the aircraft up in controlled climbs, holding their breath as manifold pressure edged toward the danger zone. But something strange happened.

The tremors that had haunted earlier versions simply never appeared. Oil temperature held steady. Cylinder head heat rose predictably instead of spiking. At 25,000 ft, where earlier engines stumbled, the improved units delivered a smooth, relentless surge that startled even the men who had been flying thunderbolts for months. In pilot diaries from that period, a phrase appears again and again.

The engine felt steady, not strong, not loud, steady. And steady in war is everything. By early spring of 1944, the P47 had become something new. A machine able to fight above 30,000 ft without tearing itself apart. A machine that could dive with such terrifying speed that German pilots learned to abandon any pursuit once a thunderbolt began its descent.

More importantly, the double wasps reliability meant pilots could now use war emergency power without the dread that had once shadowed every climb. Emergency power was supposed to last mere minutes. Yet, missions from this period are filled with accounts of pilots pushing their throttles forward to outrun ambushes to reach bomber formations collapsing under attack to break free from a swarm of faka wolves. and the engine not only accepted the punishment but still had more to give.

What strikes me reading operations reports from the spring of 44 is how the P47’s role began to shift almost immediately. It no longer struggled to stay with the bomber stream. It dominated the airspace around it. German pilots who once waited comfortably at altitude found themselves on the defensive when thunderbolts arrived overhead, diving with such speed that their machine guns created overlapping curtains of fire that shredded formations before the Germans could even turn. And behind that transformation was

not a new tactic or a new doctrine, but the ability to guarantee with startling confidence that the engine would hold together when everything else fell apart. This reliability had consequences far beyond Europe.

In the Pacific, where distances swallowed entire squadrons and heat punished engines without mercy, the double wasp became the spine of carrier aviation. The F-6F Hellcat, built around the same power plant, achieved kill ratios that seem almost fictional today. More than 5,000 enemy aircraft fell to Hellcats flown by young naval aviators who trusted implicitly that their engines would deliver full power even in the chaos of a dog fight.

And that trust, that quiet, unspoken faith in a machine came from the same microscopic correction made months earlier by hands coated in aluminum dust. But to understand the gravity of this shift, you have to step into the mind of a pilot in early 1944. Imagine climbing toward a bomber formation hammered by cannon fire.

The altimeter needle rising, the engine straining before the correction. This was the moment when pilots whispered silent please into oxygen masks. Hold together, hold together. Now those same pilots shoved the throttle past military power, felt the aircraft surge forward and knew, not hoped, not prayed, knew that the engine would answer.

This psychological shift alone changed how the thunderbolt was flown. Aggression replaced caution. Initiative replaced hesitation. The aircraft no longer felt like a heavy, unreliable brute. It felt like a hammer, and hammers reshape battlefields. Yet, what makes this turning point so haunting is how invisible it was to the world that benefited from it.

Newspapers published glowing stories about pilots. Commanders issued bold communicates. But nowhere in any official summary do you find mention of a young woman standing beside a failing engine at 7:17 a.m. recognizing the signature of a flaw that no one else had identified. The heroes in cockpits had names etched into history. The heroes at workbenches did not.

And yet their fingerprints rode into combat on every bolt of aluminum, every connecting rod, every cylinder that refused to fail when a man’s life depended on its strength. By June 1944, when the invasion of Normandy filled the sky with aircraft thicker than migrating birds, the improved double wasp had already begun rewriting the rules of the air war.

P47s struck rail lines armored columns communication hubs. They dove so hard that German flat crews sometimes fired too high. Unable to believe a fighter could survive such speeds. The Luftwaffa began to fracture under the strain, losing aircraft faster than they could be replaced, losing pilots faster than they could be trained.

Reliability had become lethality. Power had become precision. And this new chapter in the air war was built not on a new weapon, but on a correction measured in 10,000 of an inch. The war was shifting violently decisively. And yet, the most important question remained unanswered. If an engine could now survive the brutal demands of combat, what would that mean for the men who relied on it? The men whose survival curve suddenly bent upward in ways no strategist had dared predict.

to understand that we have to follow the engine from the battlefield reports into the lives of the pilots themselves. The ones who started coming home because their power plants refused to give up. They began noticing it quietly at first in the oddest places, debriefing tents, maintenance shacks, oxygen hazed cockpits, drifting back towards English fields long after they should have fallen.

A pilot would climb out of a P-47 with smoke streaking the coing flag holes stitched across the wings and instead of describing a near-death engine failure, he would say something almost unbelievable. The engine kept going. That phrase repeated over and over through the spring and summer of 1944 marked a turning point more profound than any change in strategy or leadership. The double wasp no longer felt like an engineering gamble.

It felt like a partner. And in a war where machinery failed as often as men fell, that shift meant everything. Before the correction engine failures were an accepted hazard. Pilots trained to recognize the early signs. A hesitant sputter on climb, a flicker in oil pressure, a vibration that meant they had seconds to throttle back or risk total seizure.

They knew these symptoms intimately because they killed with absolute indifference. A fighter with a dead engine at 30,000 ft became a glider at the mercy of a sky owned by the enemy. A bomber with one engine gone might limp home. A single engine fighter seldom did, but after the recalibration, after the microscopic correction that changed the engine’s internal geometry, the reports shifted in tone.

Instead of pilots praying that their engines would hold, they began trusting that they would. This trust reshaped combat behavior in ways I didn’t expect until I read the mission transcripts. Pilots who once conserved power now used war emergency power aggressively, not recklessly, but decisively. They dove harder, climbed longer, and re-engaged fights they would previously have broken off.

One squadron leader noted that his flight acrewed more confirmed kills in a single month than in the previous three combined. And he attributed it not to better tactics, but to a single factor they could stay in the fight. Staying meant survivability. Survivability meant cumulative advantage. Cumulative advantage by mid 1944 meant victory.

Maintenance records tell a parallel story. Before the redesign, mechanics worked through the night, replacing cracked bearings, warped rods, and overheated cylinders. Engines that returned from missions often required full tear down inspections. But within weeks of the new tolerances rolling into service, those catastrophic failures dropped by nearly 40%.

Mechanics began referring to the revised double wasp as the engine that refused to quit. One crew chief wrote that he had never seen an engine take so much punishment and still pass compression checks. When you read those numbers, the decrease in failures, the increase in mission completion, you begin to realize the scale of what had changed.

A war fought over thousands of miles and millions of decisions was quietly turning on a fractional correction that existed below the threshold of sight. But the true measure of impact isn’t found in data sheets. It appears in the pilot narratives from that summer. A lieutenant describes being hit during a strafing run near Can.

Flack tore through the oil cooler, shredded the lower cowl, and peppered the front cylinders with shrapnel. He expected the engine to seize. Instead, it lost power, gradually, predictably, giving him enough time to climb turn west and glide to a crash landing on a makeshift strip. He credited his survival to a robust engine and someone back home who built it right.

Another pilot wrote that he watched his wingman’s thunderbolt take a cannon shell to the nose and keep running long enough for both of them to escape a swarm of wolves. Stories like these accumulate until they stop sounding like miracles and start sounding like engineering finally aligned with necessity. What I find most compelling is the moral dimension hidden beneath the mechanical one.

Every engine that refused to die at altitude represented not just industrial competence, but a human life preserved. Hundreds of pilots came home because their engines endured conditions that earlier units never could have survived. Thousands of missions succeeded because fighters stayed aloft long enough to shepherd bombers through walls of enemy fire.

reliability became a form of mercy, cold, metallic, invisible, but mercy nonetheless. And that mercy began with a correction that no commander, no strategist, no general even knew needed to be made. Yet there is an irony here that feels almost too sharp. The pilots whose lives were saved rarely knew the cause. They thank their aircraft, their luck, their training.

They did not thank the woman in a Connecticut factory who heard a vibration that didn’t sound right. They couldn’t. They never learned her name. The war credited the machines. The machines credited no one. History moved forward without turning its gaze toward the hands that steadied the engines at the moment when the world demanded perfection. But perfection wasn’t the point. Consistency was. Predictability was.

And when those qualities finally settled into the double wasp, the air wars center of gravity shifted. The Thunderbolt, once dismissed as heavy and slow to climb, became one of the most feared weapons in the Western sky. The Hellcat, already formidable, became almost untouchable.

The Corsair dominated Pacific runways with a confidence born from the engine buried inside its blue aluminum skin. Still, a deeper question lingers. If a fractional adjustment could save thousands of airmen, what does that say about the invisible architecture of war? the way victories hinge not just on grand strategies but on unnoticed acts of precision.

To pursue that question, we must follow the engine beyond combat reports, beyond mechanical summaries into the quiet aftermath where the people who made these machines returned to lives that history rarely bothered to record. And that is where this story leads next. When the war finally loosened its grip in 1945, and the factories began to fall silent for the first time in four relentless years, something peculiar happened.

The engines stayed, the aircraft stayed, the maintenance logs, the mission reports, the casualty curves, all of it stayed. But the people who had built the machines, the ones who had bent metal into miracles, began to disappear from the story. It wasn’t intentional. History rarely erases out of malice. It erases out of momentum.

The world was racing toward peace or something that resembled it. And the hands that had held the war together were expected to return quietly to whatever lives they’d left behind. Archival photographs from late 1945 show rows of women standing beside production lines that were already winding down.

Some smile, some look exhausted in ways no camera can fully capture. Most never worked in aviation again. They traded rivet guns for grocery lists, micrometers, for children’s lunches, 12-hour shifts for the fragile hope that war work had not permanently reshaped them. And yet the transformation they embodied did not vanish.

It traveled forward, hidden uncredited inside every engine cowling bolted shut during the late stages of the conflict. The double wasp kept serving long after its creators returned to obscurity. It powered aircraft in Korea. It remained in reserve fleets into the 1950s. Its reliability became a benchmark engineers studied when designing the next generation of power plants.

But nowhere in those technical reports is there a footnote for the unnamed riveter who sensed a misalignment before anyone else or for the thousands of women who learned the mood of metal through bruised palms and burning shoulders. The engines outlived their makers and the history books outshed the quiet truth of who exactly had safeguarded the lives of so many pilots.

According to industrial surveys conducted after the war, nearly two out of every three women who worked in wartime manufacturing were never interviewed, never asked what they had contributed, never acknowledged beyond a vague reference to homefront labor. Their names slipped into the margins. Their achievements dissolved into the label of Rosie the Riveter, a symbol powerful enough to inspire posters, but too general to honor the individual brilliance, intuition, and endurance that shaped the machinery of victory.

I keep returning to a single detail in the Pratt and Whitney notes from 1943. A line so plain it could be mistaken for paperwork. Inspection of crankpin tolerances recommended following operator observation. That operator was a woman. Her correction saved engines. Those engines saved men. And history filed the moment under maintenance procedure instead of miracle.

When I read that, I can’t help but imagine her stepping away from her workstation at the end of a shift, unaware that she had just altered not only a machine, but the trajectory of an entire air campaign. If I place myself in her world, I believe she wasn’t thinking about history at all.

She was thinking about getting home, getting rest, getting ready for the next shift that would arrive too soon. The war moved on without her name. The engines moved on without her story. But the consequences of her work echoed in every pilot who came home alive in every bomber formation that reached its target, in every surviving aircraft that taxied back to its dispersal bay, with smoke curling from the cowling, but power still in the cylinders.

Her precision, her instinct became the invisible architecture of survival. And that architecture became a legacy the world never learned to credit properly. What this reveals, at least to me, is that war records victories by the visible, not the essential. Generals receive medals. Pilots receive citations. Machines receive specifications.

But the hands that make survival possible rarely receive anything at all. Yet without those hands, without those corrections measured in 10,000ths of an inch, without those quiet acts of mastery born from exhaustion and perseverance, no strategy could have succeeded. The war might have lasted longer. More bombers might have fallen. More families might have lost the men they were praying for.

So I’m left with this final question, one that lingers long after the documents close. What else in this war? What other triumphs we think we understand were actually decided by someone we will never know. Someone who stood in the right place at the right moment, listening to a machine breathe, feeling a vibration the world refused to hear.

If you believe that unseen people shaped this conflict as powerfully as any general or any ace pilot tell me below. Leave a seven to mark that recognition. Because behind every engine that roared across a hostile sky, there was a person who made sure it could. And some of those people were women whose names will never enter the official record yet, whose fingerprints remain faint but indelible on the turning points of

News

“Don’t Leave Us Here!” – German Women POWs Shocked When U.S Soldiers Pull Them From the Burning Hurt DT

April 19th, 1945. A forest in Bavaria, Germany. 31 German women were trapped inside a wooden building. Flames surrounded them….

They Banned Her “Pencil Line Test” Until It Exposed 18 Sabotaged Aircraft DT

April 12th, 1943. A cold morning inside a noisy plane factory in Long Island. Engines roared outside. Rivet guns screamed….

Inside Ford’s Cafeteria: How 1 Kitchen Fed 42,000 Workers Daily — Used More Food Than Nazi Army DT

At 5:47 a.m. on January 12th, 1943, the first shift bell rang across the Willowrun bomber plant in Ipsellante, Michigan….

America Had No Magnesium in 1940 — So Dow Extracted It From Seawater DT

January 21, 1941, Freeport, Texas. The molten magnesium glowing white hot at 1,292° F poured from the electrolytic cell into…

They Mocked His Homemade Jeep Engine — Until It Made 200 HP DT

August 14th, 1944. 0930 hours mountain pass near Monte Casino, Italy. The modified jeep screamed up the 15° grade at…

Beyond the Stage and the Stadium: Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Unveil Their Surprising New Joint Venture in Kansas City DT

KANSAS CITY, MO — In a world where celebrity business ventures usually revolve around obscure crypto currencies, overpriced skincare lines,…

End of content

No more pages to load